SARE, Vol. 56, Issue 1 | 2019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

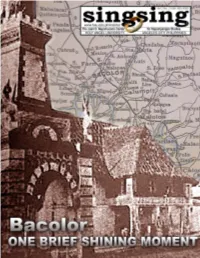

Singsing- Memorable-Kapampangans

1 Kapampangan poet Amado Gigante (seated) gets his gold laurel crown as the latest poet laureate of Pampanga; Dhong Turla (right), president of the Aguman Buklud Kapampangan delivers his exhortation to fellow poets of November. Museum curator Alex Castro PIESTANG TUGAK NEWSBRIEFS explained that early Kapampangans had their wakes, funeral processions and burials The City of San Fernando recently held at POETS’ SOCIETY photographed to record their departed loved the Hilaga (former Paskuhan Village) the The Aguman Buklud Kapampangan ones’ final moments with them. These first-of-its-kind frog festival celebrating celebrated its 15th anniversary last pictures, in turn, reveal a lot about our Kapampangans’ penchant for amphibian November 28 by holding a cultural show at ancestors’ way of life and belief systems. cuisine. The activity was organized by city Holy Angel University. Dhong Turla, Phol tourism officer Ivan Anthony Henares. Batac, Felix Garcia, Jaspe Dula, Totoy MALAYA LOLAS DOCU The Center participated by giving a lecture Bato, Renie Salor and other officers and on Kapampangan culture and history and members of the organization took turns lending cultural performers like rondalla, reciting poems and singing traditional The Center for Kapampangan Studies, the choir and marching band. Kapampangan songs. Highlight of the show women’s organization KAISA-KA, and was the crowning of laurel leaves on two Infomax Cable TV will co-sponsor the VIRGEN DE LOS new poets laureate, Amado Gigante of production of a video documentary on the REMEDIOS POSTAL Angeles City and Francisco Guinto of plight of the Malaya Lolas of Mapaniqui, Macabebe. Angeles City Councilor Vicky Candaba, victims of mass rape during World COVER Vega Cabigting, faculty and students War II. -

2014 PSC Annual Report SEC Form 17-A (PSE)

COVER SHEET 0 0 0 0 1 0 8 4 7 6 S.E.C Registration Number P H I L I P P I N E S E V E N C O R P O R A T I O N (Company’s full Name) 7 t h F l r . T h e C o l u m b i a T o w e r O r t i g a s A v e. M a n d a l u y o n g C i t y (Business Address: No. Street City / Town / Province) 724-44-41 to 51 Atty. Evelyn S. Enriquez Corporate Secretary Company Telephone Number Contact Person 1 2 3 1 1 7 . A 0 7 3rd Thursday Month Day FORM TYPE Month Day Fiscal Year Annual Meeting ANNUAL REPORT Secondary License Type, if Applicable Dept. Requiring this Doc. Amended Articles Number/Section Total Amount of Borrowings Total No. of Stockholders Domestic Foreign -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ---------- To be accomplished by SEC personnel concerned File Number LCU Document I.D. Cashier STAMPS Remarks = pls. use black ink for scanning purposes 0 SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION SEC FORM 17-A ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 17 OF THE SECURITIES REGULATION CODE AND SECTION 141 OF CORPORATION CODE 1. For the fiscal year ended 2014 2. SEC Identification Number 108476 3. BIR Tax Identification No . 000-390-189-000 4. Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter PHILIPPINE SEVEN CORPORATION 5. Philippines Province, Country or other jurisdiction of Incorporation or Organization 6. (SEC Use Only) Industry Classification Code: 7. -

Philippine Studies Ateneo De Manila University • Loyola Heights, Quezon City • 1108 Philippines

philippine studies Ateneo de Manila University • Loyola Heights, Quezon City • 1108 Philippines Balagtasan, by Zafra Review Author: Niles Jordan Breis Philippine Studies vol. 48, no. 1 (2000): 137–138 Copyright © Ateneo de Manila University Philippine Studies is published by the Ateneo de Manila University. Contents may not be copied or sent via email or other means to multiple sites and posted to a listserv without the copyright holder’s written permission. Users may download and print articles for individual, noncom- mercial use only. However, unless prior permission has been obtained, you may not download an entire issue of a journal, or download multiple copies of articles. Please contact the publisher for any further use of this work at [email protected]. http://www.philippinestudies.net Fri June 27 13:30:20 2008 BOOK REVIEWS Miss Hau also contributes two lovely fictional works, "Stories" and "The True Story of Ah To," which trace the junctures and disjunctures of the past and present. Joaquin Sy writes graceful poems in Filipino, while Melchor C. Te has a story called "Ang Lotto" which glitters with the ironies of a de Maupassant story. The other works can be edited-their narrative lines made clearer, their images made sharper, their prose pruned. But then again, that may just be the unabashed formalist in me speaking. Be that as it may, this book is a welcome addition to the monument of Philippine writing that is built with every book, every poem, story, essay, and play that we all write. Danton R. Rernoto Department of English Ateneo de Manila University Balagtasan: Kasaysayan at Antolohiya. -

Dula Dulaan Sa Filipino

DULA DULAAN SA FILIPINO Scribd is the world's largest social reading and publishing site. The two let been bowelless rivals. Calamba Metropolis. Roughly stayed by river banks and the sea, so they could angle for their nutrient. It is the beginning volume printed. Tulad ng nobela at dula. Filipino writers. Visualised as a democratic variant with illustrations by Juan Luna, this. Many of the plays were reproductions of English plays Tagalog. Maraming dakilang Pilipino, kabilang na si Rizal, ang naimpluwensyahan ng nasabing tula. On the following day, May 19, Legazpi landed in Manila and took ceremonial possession of the land in the presence of Soliman, Matanda, and Lakandula. Legazpi let them go to demonstrate his confidence in Lakandula. Isa itong masining na anyo ng panitikan. Ilocano and Visayan 7. Noli me tangere Language 3 Pages suppositious to be humourous, satiric and witty wrote the refreshing in Tagalog piece embarkment steam Melbourne in Marseilles bounce for Hongkong did. Around stayed in caves and lived on fruits and carnal centre. Tagalog Thither is no earthly joy that is not moire with weeping. Finis Baron of Tondo Rizal otc bare novels Rizal had former bare novels. They use blankets portraying coloured plumes to pull her. A few of playwriters were: 1. Mare asked the gods to consecrate her the mortal of Gat Dula and her asking was given. Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo. Si Del Pilar ang awtor ng Dasalan at Tocsohan, isang tulang tumutuligsa sa mga maling ginagawa ng mga prayle. Lakan Dula was able-bodied to counter the immunity given by Legazpi to him and to his relatives. -

ACCREDITED DENTISTS August 2018

Where beautiful smiles begin www.elitegroup.com.ph ACCREDITED DENTISTS www.elitegroup.com.ph August 2018 TABLE OF CONTENTS Area Page No. Area Page No. Area Page No. NCR – METRO MANILA 3 REGION 2 - CAGAYAN VALLEY 12 REGION 7 - CENTRAL VISAYAS 19 Caloocan City 3 Cagayan 12 Bohol 19 Las Piñas City 3 Isabela 12 Cebu 19 Makati City 3 Nueva Vizcaya 12 Malabon 4 REGION 8 - EASTERN VISAYAS 20 Mandaluyong 4 REGION 3 - CENTRAL LUZON 12 Leyte 20 Manila 5 Aurora 12 Northern Samar 20 Binondo 5 Bataan 12 Samar 20 Sta. Cruz 5 Bulacan 12 Marikina City 5 Nueva Ecija 13 REGION 9 - ZAMBOANGA PENINSULA 20 Muntinlupa City 6 Pampanga 13 Zamboanga del Sur 20 Navotas City 6 Tarlac 14 Parañaque 6 Zambales 14 REGION 10 - NORTHERN MINDANAO 21 Pasay City 7 Bukidnon 21 Pasig City 7 REGION 4A - CALABARZON 14 Lanao del Norte 21 Ortigas Center 7 Batangas 14 Misamis Occidental 21 The Medical Center 8 Cavite 15 Misamis Oriental 21 Pateros 8 Laguna 16 Quezon City 8 Quezon 17 REGION 11 - DAVAO REGION 21 Cubao 10 Rizal 17 Davao del Sur 21 Libis 10 Davao del Norte 22 Novaliches 10 REGION 4B – MIMAROPA 18 St. Lukes Medical Center 10 Occidental Mindoro 18 REGION 12 – SOCCSKSARGEN 22 San Juan 10 Oriental Mindoro 18 North Cotabato 22 Taguig 10 Palawan 18 South Cotabato 22 Valenzuela 11 Sultan Kudarat 22 REGION 5 - BICOL REGION 18 CAR – Albay 18 REGION 13 – CARAGA 22 CORDILLERA ADMINISTRATIVE REGION 11 Camarines Sur 19 Agusan del Norte 22 Benguet 11 Masbate 19 Agusan del Sur 22 REGION 1 - ILOCOS REGION 11 REGION 6 - WESTERN VISAYAS 19 ARMM 22 Ilocos Norte 11 Aklan 19 Maguindanao 22 La Union 11 Capiz 19 Pangasinan 11 Iloilo City 19 Negros Occidental 19 Page | 2 ACCREDITED DENTISTS www.elitegroup.com.ph August 2018 National Capital Region Location: opposite MCU Hospital; located at Access Computer DR. -

Real Bacolor-Layout

www.hau.edu.ph/kcenter The Juan D. Nepomuceno Center for Kapampangan Studies HOLY ANGEL UNIVERSITY ANGELES CITY, PHILIPPINES 1 RECENTRECENT VISITORS MARCH & APRIL F. Sionil Jose Ophelia Dimalanta Mayor Ding Anunciacion, Bamban, Mayor Genaro Mendoza, Tarlac City Joey Lina Sylvia Ordoñez Mayor Carmelo Lazatin, Angeles Vice Mayor Bajun Lacap, Masantol Ely Narciso, Kuliat Foundation Ching Escaler Maribel Ongpin Gringo Honasan Crisostomo Garbo Museum Foundation of the Philippines M A Y Kayakking among the mangroves in Masantol Dennis Dizon Senator Tessie Aquino Oreta Mikey Arroyo Mayor Mary Jane Ortega, San Fernando City, La Union Cecilia Leung River tours launched Ariel Arcillas, Pres, SK Natl Federation THE Center sponsored a multi-sector Congressman Bondoc promised to Mark Alvin Diaz, SK Nueva Ecija Tessie Dennis Felarca, SK Zambales research cruise down Pampanga River convert a portion of his fishponds into a Oreta Brayant Gonzales, Angeles City last summer, discovered that the river is mangroves nursery and to construct a port Council not as silted and polluted as many believe, in San Luis town where tourist boats can Vice Mayor Pete Yabut, Macabebe and as a result, organized cultural and dock. The town’s centuries-old church is Vice Mayor Emilio Capati, Guagua ecological tours in coordination with the part of the planned itinerary for church Carmen Linda Atayde, SM Department of Tourism Region 3, local gov- heritage river cruises. Other cruise options Foundation ernment units in the river communities, include a tour of the mangroves in Masantol Efren de la Cruz, ABC President Estelito Mendoza and a private boatyard owner. and Macabebe, and tours coinciding with Col. -

List of Accredited Level 1 Hospitals As of May 31, 2021

LIST OF ACCREDITED LEVEL 1 HOSPITALS AS OF MAY 31, 2021 NAME OF INSTITUTION ABC TEL_NO EMAIL STREET MUNICIPALITY START DATE EXPIRE DATE SEC HEAD OF FACILITY NATIONAL CAPITAL REGION & RIZAL METRO MANILA 1 A. ZARATE GENERAL HOSPITAL 17 874-6903 [email protected] ATLAS COMPOUND, NAGA RD., LAS PIÑAS CITY 01/01/2021 12/31/2021 P DR. ALBERT L. ZARATE PULANG LUPA, 2 ACEBEDO GENERAL HOSPITAL 16 8983-5363 [email protected] 849 GENERAL LUIS ST., BAGBAGUIN, CALOOCAN CITY 01/01/2021 12/31/2021 P DR. EDDIE D. ACEBEDO 3 ALABANG MEDICAL CENTER 18 8807-8187 TO 89 / 775- [email protected] ALABANG ZAPOTE ROAD, MUNTINLUPA CITY 01/01/2021 12/31/2021 P DR. ANITA N. TY 0511 loc 105 4 ALABANG MEDICAL CLINIC 30 842-0680 [email protected] 297 T. MONTILLANO ST., ALABANG, MUNTINLUPA CITY 01/01/2021 12/31/2021 P DR. CESAR T. SY 5 ALABANG MEDICAL CLINIC - LAS PIÑAS BRANCH 18 8874-2506/ 874-0164 / 873- [email protected] ALABANG-ZAPOTE RD. COR. LAS PIÑAS CITY 01/01/2021 12/31/2021 P DR. MA. ISIDRA APOLONIA B. MASA 6464 MENDOZA ST., PELAYO VILLAGE, TALON, 6 ALABANG MEDICAL CLINIC - MUNTINLUPA BRANCH 25 8861-1187 / 8842-1723 [email protected] 1 NATIONAL ROAD, PUTATAN, MUNTINLUPA CITY 01/01/2021 12/31/2021 P DR. MANUEL LUIS L. BARANGAN 7 ALFONSO SPECIALIST HOSPITAL 22 8571-1285 / 643-3410 / 641- [email protected] 185 DR. SIXTO ANTONIO AVE., PASIG CITY 01/01/2021 12/31/2021 P DR. JAMIE L. ALFONSO 2756 m ROSARIO, 8 BERMUDEZ POLYMEDIC HOSPITAL, INC. -

Protest Songs in EDSA 1: Decoding the People's Dream of An

PADAYON SINING: A CELEBRATION OF THE ENDURING VALUE OF THE HUMANITIES Presented at the 12th DLSU Arts Congress De La Salle University, Manila, Philippines February 20, 21 and 22, 2019 Protest Songs in EDSA 1: Decoding the People’s Dream of an Unfinished Revolution Marlon S. Delupio, Ph.D. History Department De La Salle University [email protected] Abstract: “Twenty-six years after Edsa I, also called the 1986 People Power Revolution, exactly what has changed? People old enough to remember ask the question with a feeling of frustration, while those who are too young find it hard to relate to an event too remote in time.” (Philippine Daily Inquirer, 25 of February 2012, 12) The People Power-1 Revolution (also known as EDSA Revolution of 1986 or the Yellow Revolution) was a series of mass demonstrations in the Philippines that took place from February 22-25, 1986. The nonviolent revolution led to the overthrow of then President Ferdinand Marcos that would eventually end his 21-year totalitarian rule and the restoration of democracy in the country. The quote cited above generally represent the sentiment of the people in celebrating EDSA-1 yearly, such feelings of frustration, hopelessness, indifference, and even a question of relevance, eroded the once glorified and momentous event in Philippine history. The paper aims to provide a historical discussion through textual analysis on the People Power-1 Revolution using as lens the three well known protest songs during that time namely: Bayan Ko, Handog ng Pilipino sa Mundo and Magkaisa. Protest songs are associated with a social movement of which the primary aim is to achieve socio-political change and transformation. -

Directory of Schools and Officials Sy 2013-2014

DEPED-NATIONAL CAPITAL REGION DIRECTORY OF SCHOOLS AND OFFICIALS SY 2013-2014 SCHOOL CONG. DIVISION/ LEVEL/ OFFICE / SCHOOL ADDRESS HEAD OF OFFICE/PRINCIPAL POSITION / DESIGNATION LANDLINE NUMBER(S) DISTRICT DISTRICT LAS PIÑAS CITY Division Office Diego Cera Ave, E. Aldana, Las Piñas City Mrs. Corazon C. Gonzales OIC Schools Division 8223840 ELEMENTARY Superintendent 1 Almanza ES II LONE Real St., Almanza Uno, Las Piñas City MR. ROSAURO C. ALFONSO Elementary School Principal IV 8068190 / 8054242 2 Almanza ES - T. S. Cruz Annex II LONE Ilang-Ilang St., TS Cruz Subd., Almanza Dos, Las Piñas City MS. SUSANA I. MONTAS Teacher-In-Charge 7721897 3 CAA ES I LONE Patola St., BF International Village, Las Piñas City MS. REBECCA A. MIRANDA Elementary School Principal IV 5480304 4 CAA ES Annex I LONE Tigaon St., Las Piñas City MS. JOCELYN C. BALOME Teacher-In-Charge 3851462 5 Daniel Fajardo ES I LONE San Jose St., Daniel Fajardo, Las Piñas City MR. GERONIMO A. DE VERA Elementary School Principal I 8285309 6 Dona Manuela ES II LONE Orchids St., Doña Manuela Subd., Pamplona Tres, Las Piñas MR. JOSEPH F. DE LEON Elementary School Principal II 8751171 City 7 Gatchalian ES I LONE Tolentino St., Phase V, Gatchalian Subdivision, Las Piñas MR. RONALDO B. LARA Education Supervisor I - OIC 8295573 8 Ilaya ES I LONE TramoCity St., Ilaya, Las Piñas City MS. MARY JOY C. DADOR Teacher-In-Charge 8295674 9 Las Pinas ES Central I LONE Diego Cera Ave, E. Aldana, Las Piñas City MR. FELIX. L. PERIDO Elementary School Principal II 5502856 10 Manuyo ES I LONE Tramo St., Manuyo Uno, Las Piñas City MS. -

Unitas Journal

ISSN: 0041-7149 ISSN: 2619-7987 VOL. 92 • NO. 1 • MAY 2019 UNITASsemi-annual peer-reviewed international online journal of advanced research in literature, culture, and society Transpacific Connections Razones del Modernismo of Philippine Literature in Spanish hispanoamericano en Bancarrota de EditEd by JorgE MoJarro almas de Jesús Balmori: (“Ventura bajo la lámpara eléctrica leía vagamente el A Mexican Princess in the Tagalog Azul de Darío”) Sultan’s Court: Floripes of the bEatriz barrEra Doce Pares and the Transpacific Efflorescence of Colonial Philippine Teodoro Kalaw lee a Gómez Carrillo: Romance and Theater Hacia la Tierra del Zar (1908), un John d. blanco ejemplo de crónica modernista filipina JorgE MoJarro Bad English and Fresh Spaniards: Translation and Authority in Philippine Quijote-Sancho y Ariel-Calibán: and Cuban Travel Writing La introducción de Filipinas en la ErnEst rafaEl hartwEll corriente hispanoamericanista por oposición al ocupador yankee Recuperating Rebellion: Rewriting rocío ortuño casanova Revolting Women in(to) Nineteenth-Century Cuba Transcultural Orientalism: Re-writing and the Philippines the Orient from Latin America and The kristina a. Escondo Philippines irEnE villaEscusa illÁn La hispanidad periférica en las antípodas: el filipino T. H. Pardo de Reframing “Nuestra lengua”: Tavera en la Argentina del Centenario Transpacific Perspectives on the axEl gasquEt Teaching of Spanish in the Philippines paula park From Self-Orientalization to Revolutionary Patriotism: Paterno’s Reading Military Masculinity in Fil- -

(CSHP) DOLE-National Capital Region June 2018

REGIONAL REPORT ON THE APPROVED/CONCURRED CONSTRUCTION SAFETY & HEALTH PROGRAM (CSHP) DOLE-National Capital Region June 2018 No. Company Name and Address Project Name Date Approved Healthy Options Healthy Options Festival Mall Renovation 1 2/F Topy's Place, 3 Economia St. cor. Calle Industria, 6/4/2018 Unit 2005-2006 Level 2 Festival Supermall, Muntinlupa City Bagumbayan, Quezon City Demolition and Restoration of Existing Perimeter Fence at Maynilad Water Services Inc. 2 Bagbag Reservoir 6/14/2018 MWSS Compound, Katipunan Road, Balara, Quezon City F. Delos Santos St. Sauyo Road, Novaliches, Quezon City Proposed Construction of Bank of the Philippine Island Office - Carlo Poblete 3 2nd Floor, BPI M.H. Del Pilar Branch 6/4/2018 M.H. Del Pilar corner U.N. Avenue, Ermita, Manila M.H. Del Pilar corner U.N. Avenue, Ermita, Manila Enrique Fernandez Proposed Repair of Two (2) Storey Old House 4 6/5/2018 614 Trinidad St., Sta. Cruz, Manila 614 Trinidad St., Sta. Cruz, Manila Lory Anne V. Kim Proposed Renovation of Good Friends Holdings, Inc. 5 6/5/2018 1535 M. Adriatico St., Ermita, Manila 1535 M. Adriatico St., Ermita, Manila Helen Hular Piring Proposed Construction of Perimeter Fence 6 6/5/2018 1546 N. Zamora St., Tondo, Manila 1546 N. Zamora St., Tondo, Manila Proposed Renovation of Comworks Clickstore Ma. Elizabeth M. Leyeza / Comworks Inc. 7 Unit 33, C7 030, Lower Ground Floor, SM City Manila, Ermita, 6/14/2018 CWI Corporate Center 1050 Quezon Ave., Quezon City Manila Nonito Y. Lao / BRL Food Service Management, Inc. Proposed Repair of Kiosk (Yang's Hong Kong Style Noodle) 8 6/14/2018 20 Felipe Pike St., Bagon Ilog, Pasig City Park 'N Ride, Arroceros St., Ermita, Manila Jaime Lim Proposed Repair of Residential Building 9 6/14/2018 # 3581 Mag Arellano St., Bacood, Sta. -

Philippines-USD-Payout-Locations.Pdf

Network Agent Name Agent Location Name Address Line 1 Address Line 2 City Province Postal Code Phone Code City Phone Number I-PAY COMMERCE VENTURES INC LUZON RAM CYCLES INC. - BANGUE TORRIJOS STREET ZONE 5 BANGUED ZONE 5 BANGUED ABRA 2800 I-PAY COMMERCE VENTURES INC RAMAS UYPITCHING SONS INC A BITO POBLACION ABUYOG 6510 I-PAY COMMERCE VENTURES INC LUZON RAM CYCLES INC. - AGOO L NATIONAL HIGHWAY SAN ANTONIO AGOO LA UNION 2504 I-PAY COMMERCE VENTURES INC RAMAS UYPITCHING SONS INC. - P SO UBOS REAL ST. AJUY 5012 I-PAY COMMERCE VENTURES INC LUZON RAM CYCLES INC. - ALAMIN MARCOS AVE BRGY PALAMIS ALAMINOS CITY PANGASINAN I-PAY COMMERCE VENTURES INC RAMAS UYPITCHING SONS INC. - A 50 KINABRANAN KINABRANAN ZONE I (POB.) ALLEN SAMAR 6405 I-PAY COMMERCE VENTURES INC RAMAS UYPITCHING SONS INC - AL MURAYAN POBLACION ALTAVAS 5616 I-PAY COMMERCE VENTURES INC DIGITAL PARADISE INC. - MARQUE 3RD LEVEL SPACE 3050 MARQUEE MALL ANGELES PAMPANGA 2009 HOZUM CORP 1226 CANDD MCARTHUR HIGHWAY NINOY AQUINO I-PAY COMMERCE VENTURES INC LUZON RAM CYCLES INC ANGELE MARISOL ANGELES PAMPANGA 2009 I-PAY COMMERCE VENTURES INC DIGITAL PARADISE INC (NETOPIA) P OLIVEROS 3 CORNER G MASANGKAY ST G/F/F MARIKINA VALLEY CUPANG ANTIPOLO RIZAL 1870 I-PAY COMMERCE VENTURES INC LUZON RAM CYCLES INC COGEO SITIO KASAPI MARCOS HI WAY BAGONG NAYON ANTIPOLO RIZAL 1870 I-PAY COMMERCE VENTURES INC LUZON RAM CYCLES INC MASINA 195 MARCOS HIGHWAY MAYAMOT ANTIPOLO RIZAL 1870 SUMULONG MEMORIAL CIRCLE CIRCUMFERENTIAL RD CHRISTMAR I-PAY COMMERCE VENTURES INC LUZON RAM CYCLES INC. SAN ROQ VILL ANTIPOLO RIZAL 1870 I-PAY COMMERCE VENTURES INC LUZON RAM CYCLES INC APALIT MCARTHUR HIGHWAY BRGY SAMPALOC APALIT PAMPANGA 2016 I-PAY COMMERCE VENTURES INC LUZON RAM CYCLES INC.