Drought Management Action Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 307: Texas Surface Water Quality Standards (4/9/2008)

Revisions to §307 - Texas Surface Water Quality Standards (updated November 12, 2009) EPA has not approved the revised definition of “surface water in the state” in the TX WQS, which includes an area out 10.36 miles into the Gulf of Mexico. Under the CWA, Texas does not have jurisdiction to regulate water standards more than three miles from the coast. Therefore, EPA’s approval of the items in the enclosure recognizes the state’s authority under the CWA out to three miles in the Gulf of Mexico, but does not extend past that point. Beyond three miles, EPA retains authority for CWA purposes EPA’s approval also does not include the application the TX WQS for the portions of the Red River and Lake Texoma that are located within the state of Oklahoma. Finally, EPA is not approving the TX WQS for those waters or portions of waters located in Indian Country, as defined in 18 U.S.C. 1151. The following sections have been approved by EPA and are therefore effective for CWA purposes: • §307.1. General Policy Statement • §307.2. Description of Standards • §307.3. Definitions and Abbreviations (see item under “no action” section below) • §307.4. General Criteria • §307.5. Antidegradation • §307.6. Toxic Materials. (see item under “no action” section below) • §307.7. Site-specific Uses and Criteria (see item under “no action” section below) • §307.8. Application of Standards • §307.9. Determination of Standards Attainment • Appendix C - Segment Descriptions • Appendix D - Site-specific Receiving Water Assessments The following sections have been partially approved by EPA: • Appendix A. -

Untitled Spreadsheet

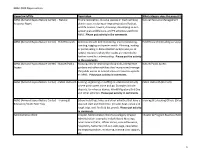

GBAC 2020 Opportunities OpportunityTitle Description What category does the project fall under ABNC (Armand Bayou Nature Center) - Natural Prairie restoration, invasive species or trash removal, Natural Resource Management Resource Mgmt plant rescue, restoring or improving natural habitat, wildlife houses, towers, chimneys, developing an eco- system plan,wildlife care, and P3 activities specific to ABNC. Please put activity in the comments. ABNC (Armand Bayou Nature Center) - Field Research Activities include bird monitoring, insect monitoring, Field Research (including surveys) banding, tagging and species watch. Planning, leading or participating in data collection and/or analysis of natural resources where the results are intended to further scientific understanding. Please put the activity in the comments. ABNC (Armand Bayou Nature Center) - Nature/Public Mowing, new or improving hiking trails, intrepretive Nature/Public Access Access gardens and other activities that improve and manage the public access to natural areas or resources specific to ABNC. Please put activity in comments. ABNC (Armand Bayou Nature Center) - Public Outreach Leading, organizing or staffing an educational activity Public Outreach (Indirect) where participants come and go. Examples include docents, farm house demos, World Migratory Bird Day and other activities. Please put activity in comments. ABNC (Armand Bayou Nature Center) - Training & School Field trips, hikes and other activities that have a Training & Educating Others (Direct) Education/Youth Field Trips planned start and finish time. Includes boat, canoe and kayak trips, owl, firefly & bat prowls. Please put activity in comments. Administrative Work Chapter Administration WorkSub-category Chapter Chapter & Program Business/Administration Administration: examples include Board Meetings, hours administrator, officer duties, committee work, hospitality, Samaritan roll-out, web page, newsletter, training preparation, mentoring, training class support, etc. -

The Proposed Fastrill Reservoir in East Texas: a Study Using

THE PROPOSED FASTRILL RESERVOIR IN EAST TEXAS: A STUDY USING GEOGRAPHIC INFORMATION SYSTEMS Michael Ray Wilson, B.S. Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS December 2009 APPROVED: Paul Hudak, Major Professor and Chair of the Department of Geography Samuel F. Atkinson, Minor Professor Pinliang Dong, Committee Member Michael Monticino, Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Wilson, Michael Ray. The Proposed Fastrill Reservoir in East Texas: A Study Using Geographic Information Systems. Master of Science (Applied Geography), December 2009, 116 pp., 26 tables, 14 illustrations, references, 34 titles. Geographic information systems and remote sensing software were used to analyze data to determine the area and volume of the proposed Fastrill Reservoir, and to examine seven alternatives. The controversial reservoir site is in the same location as a nascent wildlife refuge. Six general land cover types impacted by the reservoir were also quantified using Landsat imagery. The study found that water consumption in Dallas is high, but if consumption rates are reduced to that of similar Texas cities, the reservoir is likely unnecessary. The reservoir and its alternatives were modeled in a GIS by selecting sites and intersecting horizontal water surfaces with terrain data to create a series of reservoir footprints and volumetric measurements. These were then compared with a classified satellite imagery to quantify land cover types. The reservoir impacted the most ecologically sensitive land cover type the most. Only one alternative site appeared slightly less environmentally damaging. Copyright 2009 by Michael Ray Wilson ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to acknowledge my thesis committee members, Dr. -

07-77817-02 Final Report Dickinson Bayou

Dickinson Bayou Watershed Protection Plan February 2009 Dickinson Bayou Watershed Partnership 1 PREPARED IN COOPERATION WITH TEXAS COMMISSION ON ENVIRONMENTAL QUALITY AND U.S. ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION AGENCY The preparation of this report was financed though grants from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency through the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES ............................................................................................................................................ 7 LIST OF TABLES .............................................................................................................................................. 8 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ................................................................................................................................. 9 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................................................ 10 SUMMARY OF MILESTONES ........................................................................................................................ 13 FORWARD ................................................................................................................................................... 17 1. INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................................................... 18 The Dickinson Bayou Watershed .................................................................................................................. -

Houston a Year After Harvey: Where We Are and Where We Need to Be Presentation by Jim Blackburn Baker Institute and Bayou City Initiative August 30, 2018

Houston A Year After Harvey: Where We Are and Where We Need To Be Presentation By Jim Blackburn Baker Institute and Bayou City Initiative August 30, 2018 Harris County Watersheds Population By Watershed Homes Flooded DuringNumber of Harvey Homes By Watershed Flooded in Hurricane Harvey 26,750 30,000 24,730 25,000 20,000 17,090 14,880 15,000 9,450 12,370 11,980 9,120 7,420 3,790 10,000 6,010 2,200 1,890 510 2,720 5,000 310 1,910 230 190 0 490 0 Percentage of Population with Flooded Homes - Per Watershed 0% 2% 4% 6% 8% 10% 12% Spring Creek Watershed 1% Willow Creek Watershed 1% Addicks Watershed 2% Barker Watershed 2% Luce Bayou Watershed 2% Armand Bayou Watershed 3% Cypress Creek Wshed. (w/ Little Cypr. Crk) 3% Galveston Bay Drainage 3% Vince Bayou Watershed 3% White Oak Bayou Watershed 3% Buffalo Bayou Watershed 4% Brays Bayou Wshed. (w/Willow Waterhole) 4% Spring Gulley & Goose Crk. Watershed 4% Greens Bayou Wshed. (w/Halls Bayou) 5% Sims Bayou Wshed. (w/Berry Bayou) 5% San Jacinto River Wshed. (w/Ship Channel) 5% Cedar Bayou Watershed 6% Clear Creek Watershed (w/Turkey Creek) 7% Hunting Bayou Watershed 10% Percentage of Population with Flooded Homes - Per Watershed 0% 2% 4% 6% 8% 10% 12% Spring Creek Watershed 1% Willow Creek Watershed 1% Addicks Watershed 2% Barker Watershed 2% Luce Bayou Watershed 2% Armand Bayou Watershed 3% Cypress Creek Wshed. (w/ Little Cypr. Crk) 3% Galveston Bay Drainage 3% Vince Bayou Watershed 3% White Oak Bayou Watershed 3% Buffalo Bayou Watershed 4% Brays Bayou Wshed. -

Texas Water Resources Institute

Texas Water Resources Institute Summer 1989 Volume 15 No. 2 Optimizing Reservoir Management New Strategies Including Systems Operation and Reallocation May Boost Reservoir Yields By Ric Jensen Information Specialist, TWRI Many experts believe Texas can increase its surface water supplies without building new dams and reservoirs. The answer isn't magic. The solution is better management and coordination of existing reservoirs. New strategies/hat make every drop of water count include operating a group of reservoirs as a coordinated system; converting some reservoir storage space from hydropower production, flood control, and navigation to water supplies; and timing water levels in reservoirs to correspond to seasonal differences in streamflows and water demands. Scientists are learning more about the quality of water in lakes and how man's activities affect the chemical makeup of reservoirs. A number of important developments are already taking place. Both the City of Dallas and the Brazos River Authority manage their reservoir systems so that releases of water are tied to climate conditions water demands. The Lower Colorado River Authority (LCRA) has recently submitted a management plan to the Texas Water Commission (TWC) that could allow LCRA to sell "interruptible water supplies" during wet years. Opportunities to reallocate storage space in Texas reservoirs have been summarized in recent report by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (COE). Otherstudies have described how systems operation could increase water supplies in reservoirs in the Sabine, Trinity, and Trinity-San Jacinto River basins. 1 Optimizing reservoir management has been the focus of many university research projects. Scientists at Texas A&M University have been studying the Brazos River basin. -

Wetlands and Reefs: Two Key Habitats

CHAPTER SEVEN Wetlands and Reefs: Two Key Habitats The plants, predominantly grasses, that flourish in this environment (East Bay Wetlands) serve two biological functions: productivity and protection. From the amount of reduced carbon fixed by these plants during photosynthesis, this ecotone must be considered one of the most productive areas in the world and truly the pantry of the oceans. The dense stand of grass also represents a jungle of roots, stems, and leaves in which the organisms of the marsh, the "peel- ers, " larvae, fry, "bobs," and fingerlings seek refuge from predators. -Frank Fisher, Jr., The Wetlands, Rice University Review, 1972 he Galveston Bay system is composed of a variety of ic systems where the water table is usually at or near the surface, habitat types, ranging from open water areas to wetlands or the land is covered by shallow water (Cowardin et al, 1979). and upland grasslands. These habitats support specific Wetlands in Galveston Bay play several key ecological roles in plant, fish, and wildlife species and contribute to the protecting and maintaining the health and productivity of the estu- T ary. tremendous diversity and overall abundance of bay life. Several specific habitat types have been identified and described in the Galveston Bay system (see FIGURE 2.4). The importance of these The Origin and Importance of Wetlands habitats, their internal functions, and their interconnectedness were Wetlands were formed in Galveston Bay from the long-term presented in Chapter Three as a conceptual model of the bay interaction of the ecosystem's physical processes. These processes ecosystem. The continued productivity and biological diversity of include rainfall and runoff, water table fluctuations, streamflow, the estuarine system is dependent upon the maintenance of varied evapotranspiration, waves and longshore currents, astronomical and abundant high-quality habitat. -

Serendipity" in Action: Hana Ginzbarg and the Crusade to Save Armand Bayou, 1970-1975

East Texas Historical Journal Volume 54 Issue 1 Article 7 2016 "Serendipity" in Action: Hana Ginzbarg and the Crusade to Save Armand Bayou, 1970-1975 Alex J. Borger Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ethj Part of the United States History Commons Tell us how this article helped you. Recommended Citation Borger, Alex J. (2016) ""Serendipity" in Action: Hana Ginzbarg and the Crusade to Save Armand Bayou, 1970-1975," East Texas Historical Journal: Vol. 54 : Iss. 1 , Article 7. Available at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ethj/vol54/iss1/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the History at SFA ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in East Texas Historical Journal by an authorized editor of SFA ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Vol. 54 Spring 2016 Number 1 "Serendipity" in Action: Hana Ginzbarg and the Crusade to Save Armand Bayou, 1970-1975 BY ALEX J. BORGER Once a land of tall-grass prairies and an interconnecting system of coastal bayous, the Houston area and the Texas Gulf Coast are now dominated by an extensive sprawl of unchecked residential, commercial, and industrial development. Up against such a formidable human enterprise, wild nature has had little opportunity to thrive. The few natural areas that have managed to survive in the region-usually small patches of quasi-wilderness, nestled between chemical plants, office buildings, shopping centers or subdivisions-are an invaluable resource for recreation and eco-education. Some are also havens for a number of critical flora and fauna that have suffered years of habitat destruction from development or pollution. -

Texas-Oklahoma Passenger Rail Study Service-Level Draft

Appendix K Archaeological Sites Technical Study In coordination with Oklahoma DOT Archaeological Sites Technical Study Prepared by July 2016 Contents Abbreviations and Acronyms ................................................................................................................... v 1.0 Introduction .............................................................................................................................. 1-1 1.1 Service Type Descriptions .............................................................................................. 1-4 1.1.1 Conventional Rail .......................................................................................................... 1-4 1.1.2 Higher-Speed Rail ......................................................................................................... 1-4 1.1.3 High-Speed Rail ............................................................................................................. 1-4 1.2 Alternative Descriptions ................................................................................................. 1-5 1.2.1 No Build Alternative ...................................................................................................... 1-5 1.2.2 Northern Section: Oklahoma City to Dallas and Fort Worth ....................................... 1-6 1.2.3 Central Section: Dallas and Fort Worth to San Antonio ............................................. 1-7 1.2.4 Southern Section: San Antonio to South Texas ......................................................... -

Armand Bayou Watershed Plan Cover: Top Left Photo Courtesy Armand Bayou Nature Center; All Other Photos © Cliff Meinhardt Armand Bayou Watershed Plan Phase I

Armand Bayou Watershed Plan COVER: TOP LEFT PHOTO COURTESY ARMAND BAYOU NATURE CENTER; ALL OTHER PHOTOS © CLIFF MEINHARDT Armand Bayou Watershed Plan Phase I A Report of the Coastal Coordination Council Pursuant to National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Award No. NA170Z1140 Production of this document supported in part by Institutional Grant NA16RG1078 to Texas A&M University from the National Sea Grant Office, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, U.S. Department of Commerce, and a grant from ExxonMobil Coporation ii PHOTO © CLIFF MEINHARDT Contents Acknowledgements .......................................................................................................................................................1 Executive Summary .......................................................................................................................................................2 Introduction .............................................................................................................................................................2 The Armand Bayou Watershed Partnership ..................................................................................................................2 State of the Watershed ..............................................................................................................................................2 Institutional Framework ..............................................................................................................................................3 -

Take Area Sublease Program

Town of Sunnyvale, Texas Lake Ray Hubbard Take Area TAKE AREA SUBLEASE PROGRAM Program Outline I. Lake Ray Hubbard Take Area Defined II. Take Area Lease Program Authority III. Municipal Regulation in the Take Area IV. Purpose of the Residential Sublease Program V. Authority of Sublease Program Administration VI. Eligibility of Properties for Sublease VII. Subleased Take Area VIII. Non-Subleased Take Area IX. Non-Conforming Land Uses within the Take Area X. Survey of Take Area Sublease Boundaries XI. Take Area Sublease Boundaries XII. Sublease Area Side Boundary - Dispute Resolution XIII. Permit Requirements for Improvements in the Take Area XIV. Residential Sublease Area Improvement Permit Requirements XV. Establishing Sublease Rates I. Lake Ray Hubbard Take Area Defined The City of Dallas built and owns Lake Ray Hubbard. The City of Dallas incorporated the lake into the City of Dallas corporate limits and maintains the lake as a reservoir. The Take Line is defined as the perimeter boundary of Dallas’ property and Dallas’ corporate limits. The Take Line is commonly the rear property line of an adjacent property-owner’s property. The Take Area is defined as the land owned by the City of Dallas between the Take Line and the normal lake pool elevation of 435.5 mean sea level. II. Take Area Lease Program Authority The Town of Sunnyvale and the City of Dallas entered into an Interlocal Agreement and Lease on September 13, 2017, providing for the lease of the Take Area from the City of Dallas to the Town of Sunnyvale and the subsequent sublease of certain portions of the Take Area to adjacent residential property owners. -

Reports GBNEP/GBEP Publications

Academic Calendar | Campus Calendar | HOWDY Portal | Phonebook | Directions Search Prospective Students | Current Students | Former Students | Visitors | Veterans | AZ List TAMUG Home Galveston Bay Information Center GBIC Resources GBNEP/GBEP Publications Galveston Bay Facts Audiovisual List Maps List Government Links Teachers' Page GBNEP/GBEP Publications The most comprehensive summaries of technical and management information are found in the following documents: Environmental Institute of Houston, University of Houston‐Clear Lake. 2002. State of the Bay: A Characterization of the Galveston Bay Ecosystem, 2nd edition GBNEP. 1994. The State of the Bay: A Characterization of the Galveston Bay Ecosystem. GBNEP‐44. Webster, Texas. 232 pages. GBNEP. 1994. The Galveston Bay Plan: The Comprehensive Conservation and Management Plan for the Galveston Bay Ecosystem. GBNEP‐49. Webster, Texas. 457 pages. GBEP. 2001. 5‐year Plan Review (1996‐2000). 88 pages. The following listing includes all publications produced by the Galveston Bay Estuary Program, 1989 ‐ 2003. Some of these publications are available free of charge from the Galveston Bay Estuary Program Ofӷice or the Galveston Bay Information Center (as supplies allow). Some are out of print. All works are available on loan from the Galveston Bay Information Center. Reports GBNEP‐1. (PDF) 1989. Galveston Bay National Estuary Program EPA/State Management Conference Agreement. Webster, Texas. 28 pages. GBNEP‐2. (PDF) 1989. Galveston Bay National Estuary Program Fiscal Year 1990 Work Plan. GBNEP‐3. (PDF) 1989. Galveston Bay National Estuary Program Member Directory. Webster, Texas. 33 pages. GBNEP‐4. (PDF) 1990. Directory of Participants. Webster, Texas. 21 pages. GBNEP‐5. (PDF) 1990. Galveston Bay National Estuary Program Fiscal Year 1991 Work Plan.