Serendipity" in Action: Hana Ginzbarg and the Crusade to Save Armand Bayou, 1970-1975

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Untitled Spreadsheet

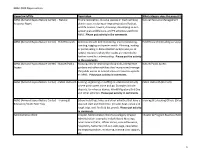

GBAC 2020 Opportunities OpportunityTitle Description What category does the project fall under ABNC (Armand Bayou Nature Center) - Natural Prairie restoration, invasive species or trash removal, Natural Resource Management Resource Mgmt plant rescue, restoring or improving natural habitat, wildlife houses, towers, chimneys, developing an eco- system plan,wildlife care, and P3 activities specific to ABNC. Please put activity in the comments. ABNC (Armand Bayou Nature Center) - Field Research Activities include bird monitoring, insect monitoring, Field Research (including surveys) banding, tagging and species watch. Planning, leading or participating in data collection and/or analysis of natural resources where the results are intended to further scientific understanding. Please put the activity in the comments. ABNC (Armand Bayou Nature Center) - Nature/Public Mowing, new or improving hiking trails, intrepretive Nature/Public Access Access gardens and other activities that improve and manage the public access to natural areas or resources specific to ABNC. Please put activity in comments. ABNC (Armand Bayou Nature Center) - Public Outreach Leading, organizing or staffing an educational activity Public Outreach (Indirect) where participants come and go. Examples include docents, farm house demos, World Migratory Bird Day and other activities. Please put activity in comments. ABNC (Armand Bayou Nature Center) - Training & School Field trips, hikes and other activities that have a Training & Educating Others (Direct) Education/Youth Field Trips planned start and finish time. Includes boat, canoe and kayak trips, owl, firefly & bat prowls. Please put activity in comments. Administrative Work Chapter Administration WorkSub-category Chapter Chapter & Program Business/Administration Administration: examples include Board Meetings, hours administrator, officer duties, committee work, hospitality, Samaritan roll-out, web page, newsletter, training preparation, mentoring, training class support, etc. -

07-77817-02 Final Report Dickinson Bayou

Dickinson Bayou Watershed Protection Plan February 2009 Dickinson Bayou Watershed Partnership 1 PREPARED IN COOPERATION WITH TEXAS COMMISSION ON ENVIRONMENTAL QUALITY AND U.S. ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION AGENCY The preparation of this report was financed though grants from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency through the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES ............................................................................................................................................ 7 LIST OF TABLES .............................................................................................................................................. 8 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ................................................................................................................................. 9 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................................................ 10 SUMMARY OF MILESTONES ........................................................................................................................ 13 FORWARD ................................................................................................................................................... 17 1. INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................................................... 18 The Dickinson Bayou Watershed .................................................................................................................. -

Houston a Year After Harvey: Where We Are and Where We Need to Be Presentation by Jim Blackburn Baker Institute and Bayou City Initiative August 30, 2018

Houston A Year After Harvey: Where We Are and Where We Need To Be Presentation By Jim Blackburn Baker Institute and Bayou City Initiative August 30, 2018 Harris County Watersheds Population By Watershed Homes Flooded DuringNumber of Harvey Homes By Watershed Flooded in Hurricane Harvey 26,750 30,000 24,730 25,000 20,000 17,090 14,880 15,000 9,450 12,370 11,980 9,120 7,420 3,790 10,000 6,010 2,200 1,890 510 2,720 5,000 310 1,910 230 190 0 490 0 Percentage of Population with Flooded Homes - Per Watershed 0% 2% 4% 6% 8% 10% 12% Spring Creek Watershed 1% Willow Creek Watershed 1% Addicks Watershed 2% Barker Watershed 2% Luce Bayou Watershed 2% Armand Bayou Watershed 3% Cypress Creek Wshed. (w/ Little Cypr. Crk) 3% Galveston Bay Drainage 3% Vince Bayou Watershed 3% White Oak Bayou Watershed 3% Buffalo Bayou Watershed 4% Brays Bayou Wshed. (w/Willow Waterhole) 4% Spring Gulley & Goose Crk. Watershed 4% Greens Bayou Wshed. (w/Halls Bayou) 5% Sims Bayou Wshed. (w/Berry Bayou) 5% San Jacinto River Wshed. (w/Ship Channel) 5% Cedar Bayou Watershed 6% Clear Creek Watershed (w/Turkey Creek) 7% Hunting Bayou Watershed 10% Percentage of Population with Flooded Homes - Per Watershed 0% 2% 4% 6% 8% 10% 12% Spring Creek Watershed 1% Willow Creek Watershed 1% Addicks Watershed 2% Barker Watershed 2% Luce Bayou Watershed 2% Armand Bayou Watershed 3% Cypress Creek Wshed. (w/ Little Cypr. Crk) 3% Galveston Bay Drainage 3% Vince Bayou Watershed 3% White Oak Bayou Watershed 3% Buffalo Bayou Watershed 4% Brays Bayou Wshed. -

Wetlands and Reefs: Two Key Habitats

CHAPTER SEVEN Wetlands and Reefs: Two Key Habitats The plants, predominantly grasses, that flourish in this environment (East Bay Wetlands) serve two biological functions: productivity and protection. From the amount of reduced carbon fixed by these plants during photosynthesis, this ecotone must be considered one of the most productive areas in the world and truly the pantry of the oceans. The dense stand of grass also represents a jungle of roots, stems, and leaves in which the organisms of the marsh, the "peel- ers, " larvae, fry, "bobs," and fingerlings seek refuge from predators. -Frank Fisher, Jr., The Wetlands, Rice University Review, 1972 he Galveston Bay system is composed of a variety of ic systems where the water table is usually at or near the surface, habitat types, ranging from open water areas to wetlands or the land is covered by shallow water (Cowardin et al, 1979). and upland grasslands. These habitats support specific Wetlands in Galveston Bay play several key ecological roles in plant, fish, and wildlife species and contribute to the protecting and maintaining the health and productivity of the estu- T ary. tremendous diversity and overall abundance of bay life. Several specific habitat types have been identified and described in the Galveston Bay system (see FIGURE 2.4). The importance of these The Origin and Importance of Wetlands habitats, their internal functions, and their interconnectedness were Wetlands were formed in Galveston Bay from the long-term presented in Chapter Three as a conceptual model of the bay interaction of the ecosystem's physical processes. These processes ecosystem. The continued productivity and biological diversity of include rainfall and runoff, water table fluctuations, streamflow, the estuarine system is dependent upon the maintenance of varied evapotranspiration, waves and longshore currents, astronomical and abundant high-quality habitat. -

Armand Bayou Watershed Plan Cover: Top Left Photo Courtesy Armand Bayou Nature Center; All Other Photos © Cliff Meinhardt Armand Bayou Watershed Plan Phase I

Armand Bayou Watershed Plan COVER: TOP LEFT PHOTO COURTESY ARMAND BAYOU NATURE CENTER; ALL OTHER PHOTOS © CLIFF MEINHARDT Armand Bayou Watershed Plan Phase I A Report of the Coastal Coordination Council Pursuant to National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Award No. NA170Z1140 Production of this document supported in part by Institutional Grant NA16RG1078 to Texas A&M University from the National Sea Grant Office, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, U.S. Department of Commerce, and a grant from ExxonMobil Coporation ii PHOTO © CLIFF MEINHARDT Contents Acknowledgements .......................................................................................................................................................1 Executive Summary .......................................................................................................................................................2 Introduction .............................................................................................................................................................2 The Armand Bayou Watershed Partnership ..................................................................................................................2 State of the Watershed ..............................................................................................................................................2 Institutional Framework ..............................................................................................................................................3 -

Reports GBNEP/GBEP Publications

Academic Calendar | Campus Calendar | HOWDY Portal | Phonebook | Directions Search Prospective Students | Current Students | Former Students | Visitors | Veterans | AZ List TAMUG Home Galveston Bay Information Center GBIC Resources GBNEP/GBEP Publications Galveston Bay Facts Audiovisual List Maps List Government Links Teachers' Page GBNEP/GBEP Publications The most comprehensive summaries of technical and management information are found in the following documents: Environmental Institute of Houston, University of Houston‐Clear Lake. 2002. State of the Bay: A Characterization of the Galveston Bay Ecosystem, 2nd edition GBNEP. 1994. The State of the Bay: A Characterization of the Galveston Bay Ecosystem. GBNEP‐44. Webster, Texas. 232 pages. GBNEP. 1994. The Galveston Bay Plan: The Comprehensive Conservation and Management Plan for the Galveston Bay Ecosystem. GBNEP‐49. Webster, Texas. 457 pages. GBEP. 2001. 5‐year Plan Review (1996‐2000). 88 pages. The following listing includes all publications produced by the Galveston Bay Estuary Program, 1989 ‐ 2003. Some of these publications are available free of charge from the Galveston Bay Estuary Program Ofӷice or the Galveston Bay Information Center (as supplies allow). Some are out of print. All works are available on loan from the Galveston Bay Information Center. Reports GBNEP‐1. (PDF) 1989. Galveston Bay National Estuary Program EPA/State Management Conference Agreement. Webster, Texas. 28 pages. GBNEP‐2. (PDF) 1989. Galveston Bay National Estuary Program Fiscal Year 1990 Work Plan. GBNEP‐3. (PDF) 1989. Galveston Bay National Estuary Program Member Directory. Webster, Texas. 33 pages. GBNEP‐4. (PDF) 1990. Directory of Participants. Webster, Texas. 21 pages. GBNEP‐5. (PDF) 1990. Galveston Bay National Estuary Program Fiscal Year 1991 Work Plan. -

Harris County, Texas and Incorporated Areas VOLUME 1 of 12

Harris County, Texas and Incorporated Areas VOLUME 1 of 12 COMMUNITY NAME COMMUNITY NO. COMMUNITY NAME COMMUNITY NO. Baytown, City of 485456 Nassau Bay, City of 485491 Bellaire, City of 480289 Pasadena, City of 480307 Bunker Hill Village, City of 1 480290 Pearland, City of 480077 Deer Park, City of 480291 Piney Point Village, City of 480308 El Lago, City of 485466 Seabrook, City of 485507 Galena Park, City of 480293 Shoreacres, City of 485510 Hedwig Village, City of1 480294 South Houston, City of 480311 Hilshire Village, City of 480295 Southside Place, City of 480312 Houston, City of 480296 Spring Valley Village, City of 480313 Humble, City of 480297 Stafford, City of 480233 Hunter’s Creek Village, City of 480298 Taylor Lake Village, City of 485513 Jacinto City, City of 480299 Tomball, City of 480315 Jersey Village, City of 480300 Webster, City of 485516 La Porte, City of 485487 West University Place, City of 480318 Missouri City, City of 480304 Harris County Unincorporated Areas 480287 Morgans Point, City of 480305 1 No Special Flood Hazard Areas identified REVISED: November 15, 2019 FLOOD INSURANCE STUDY NUMBER 48201CV001G NOTICE TO FLOOD INSURANCE STUDY USERS Communities participating in the National Flood Insurance Program have established repositories of flood hazard data for floodplain management and flood insurance purposes. This Flood Insurance Study may not contain all data available within the repository. It is advisable to contact the community repository for any additional data. Part or all of this Flood Insurance Study may be revised and republished at any time. In addition, part of this Flood Insurance Study may be revised by the Letter of Map Revision process, which does not involve republication or redistribution of the Flood Insurance Study. -

Greater Baytown NEWCOMERS GUIDE

Welcome to Greater Baytown NEWCOMERS GUIDE A special publication by The Baytown Sun | Section C | ursday, July 25, 2019 Thursday, July 25, 2019 The Baytown Sun 3 6051 GARTH RD. STE 300 281-839-7949 Baytown • Mont Belvieu • Dayton WELCOME TO BAYTOWN, WHERE WORLD CLASS CARDIAC CARE IS AVA ILABLE RIGHT AT YOUR DOORSTEP! Shehzad Sami, MD, FACC, FSCAI DrD . SamiS i isi one off a fewf cardiologistsdi l i t ini theth countryt tot hhave 5 boardb d certifitifi cationsti including Internal Medicine, Cardiovascular Disease, Interventional Cardiology, Nuclear Cardiology and Echocardiography Same day appointments • Free Convenient Parking ALL CARDIAC TESTS DONE IN THE OFFICE FOR YOUR CONVENIENCE On-site blood draws and laboratory Test reports and records shared electronically with your primary care physician and other doctors NON INVASIVE CARDIAC SERVICES INVASIVE CARDIAC SERVICES • ECG - (Paperless & Digital) • Coronary Angiogram • Echocardiogram • Coronary Stenting • Nuclear Stress Test • Cardiac Pacemakers • Carotid Doppler Ultrasound PREVENTIVE SERVICES • Holter Monitor • Calculation, 10-year risk of heart disease • Ankle Brachial Index • Stroke prevention and treatment www.HoustonCardiovascularInstitute.com “They say the heart is the strongest muscle of the body. It has to be, to carry all the love for our family and friends, our hopes and dreams.” - Shehzad Sami, MD FACC FSCAI Thursday, July 25, 2019 The Baytown Sun 3 Welcome to the City of Baytown! A City on the Move Baytown is a great place to live. You’ve 16. For more in-depth coverage of current Baytown is an excellent place to live. We a dog park, disc golf course and more. Lit- made an excellent choice in relocating affairs, look for “The Bridge” – an eight always brag that our biggest asset is our peo- tle League, Optimist and City sports teams here. -

Fall Volume 17, Number 3

GATEWAYFall 2009 Volume 17, Number 3 New Generation of Exploration From Webster to the Moon, Mars, and Beyond The Gateway magazine and archived issues are available online at... www.cityofwebster.com In This Issue Fiscally Fit for 2009-2010 .....................................................................................3 “Webster Goes Green” Reaps Top Honors ...................................................3 Flags and Fireworks ...............................................................................................4 A New Generation of Exploration ....................................................................6 Health & Wellness Fair .........................................................................................8 Senior Game Days .................................................................................................8 Faces Behind the City ..........................................................................................8 Animal Control Relocates Colubrids ................................................................8 Fifty Years as an Attorney ...................................................................................9 Records Retention Day ........................................................................................9 Fire Prevention Week ...........................................................................................9 Yards of the Month ..............................................................................................10 Martin in Webster, will -

TWS Schedule

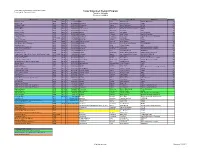

Texas State Soil and Water Conservation Board Texas Watershed Steward Program Texas AgriLife Extension Service Tentative Schedule Revised 1/14/2012 Watershed Type FY Q Date City County Contact Name Affiliation Attended Plum Creek 1 WPP 2008 2 12/04/2007 Kyle Hays Nikki Dictson AgriLife Extension 42 Buck Creek WPP 2008 2 01/24/2008 Wellington Collingsworth Lucas Gregory TWRI 37 Gilleland Creek TMDL 2008 3 03/25/2008 Pflugerville Travis Alicia Reinmund LCRA 86 Brady Creek WPP 2008 3 04/02/2008 Brady McCulloch Fred Teagarden/Chuck Brown UCRA 41 Bastrop Bayou WPP 2008 3 05/30/2008 Lake Jackson Brazoria Carl Masterson/Om Chawla HGAC 30 Granger, Lake WPP 2008 4 06/10/2008 Georgetown Williamson Jay Bragg BRA 38 Hickory Creek WPP 2008 4 07/23/2008 Denton Denton Ken Banks City of Denton 115 Plum Creek 2 WPP 2008 4 08/06/2008 Lockhart Caldwell Nikki Dictson AgriLife Extension 85 Lampasas River WPP 2009 1 09/25/2008 Lampasas Lampasas Steve Potter AgriLife Research - Blackland 59 Leon River WPP/TMDL 2009 1 10/30/2008 Comanche Comanche Jay Bragg BRA 59 Arroyo Colorado WPP 2009 1 11/20/2008 Monte Alto Hidalgo Cecilia Wagner TWRI 56 San Bernard River WPP 2009 2 01/21/2009 West Columbia Brazoria Aubin Phillips HGAC 34 Little Brazos River Tributaries Other 2009 3 03/03/2009 Franklin Robertson Loren Henley/Jay Bragg TSSWCB/BRA 29 Granbury, Lake WPP 2009 4 06/30/2009 Granbury Hood Tiffany Morgan BRA 41 Eagle Mountain Reservoir WPP 2009 4 07/15/2009 Fort Worth Parker/Tarrant Clint Wolfe AgriLife Research - Dallas 71 Cedar Creek Reservoir 1 WPP 2009 4 08/25/2009 -

Armand Bayou Nature Center's Wetlands Curriculum Grades 1

Armand Bayou Nature Center A Non-Profit Organization 8500 Bay Area Blvd, P.O. Box 58828, Houston, TX 77258 Phone – 281 474 2551, Fax – 281 474 2552, www.abnc.org “Reconnecting People with Nature” Armand Bayou Nature Center’s Wetlands Curriculum Grades 1 - 5 Armand Bayou Nature Center’s “Reconnecting People with Nature” Wetlands Curriculum Guide was prepared by a grant from the Galveston Bay Estuary Program (GBEP), a program of the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ). GBEP’s Mission is to “Preserve Galveston Bay for Generations to Come”. 1 June 2005 Table of Contents Topic Page Introduction 3 Wetlands – What are They 3 ABNC’s Wetlands Complex 3 Significance of Wetlands 4 Why Worry About Wetlands 4 Life Without Wetlands – Not a Pretty Picture 5 We All Can Protect Our Valuable Wetlands 5 Summary 6 Glossary 8 Appendix 1.A - ABNC Wetlands References – Activities 9 Appendix 1.B - ABNC Wetlands References - Website 10 Appendix 2 – ABNC Wetlands Science Experiments Appendix 3 – Other Wetlands References Appendix 4 – ABNC Field Guide References 2 June 2005 Armand Bayou Nature Center Wetlands Education Curriculum Introduction Armand Bayou Nature Center (ABNC) is a 2,500 acre nature preserve in the highly urbanized area between NASA’s Johnson Space Center and the Bayport Industrial District. ABNC is literally “Nature at your Doorstep”. ABNC protects three vanishing Gulf Coast habitats, including coastal flatwood forest, coastal tall grass prairie and an unchannelized estuarine bayou with surrounding wetlands. The ABNC preserve is home to more than 370 species of birds, mammals, reptiles and amphibians. More than 220 species of birds either reside at the center or use it as a safe resting place on their long migratory journeys. -

Chapter 6 – State of the Bay, Third Edition

CHAPTER 6 – STATE OF THE BAY, THIRD EDITION Water and Sediment Quality Written & Revised by Lisa A. Gonzalez The wondrous nature of water, that it is at once the “universal solvent” and the global transport system for molecules and masses of debris alike, also makes it particularly vulnerable to debilitating, sometimes lethal, contamination. —Sylvia A. Earle in Sea Change: A Message of the Oceans (1995) Introduction Water pollution in the Houston-Galveston region first became a public concern in the early 1900s with the recognition that sewage contributed pathogenic bacteria to area waterways. In the 1920s, oil pollution in the Houston Ship Channel prompted local and state officials to voice concerns about industrial contamination (Melosi et al. 2007). In 1967, federal investigators identified the Houston Ship Channel as “the worst example of water pollution … observed in Texas” (Melosi and Pratt 2007). This prompted the Texas Water Quality Board (now the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality, TCEQ) to initiate corrective measures to improve the water quality of the Houston Ship Channel and Galveston Bay even prior to the passage of the Clean Water Act in 1972. The portion of the Houston Ship Channel above Morgan's Point (near La Porte) was later listed among the 10 most polluted water bodies in the United States by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Stringent discharge goals were established in 1971 for industrial and municipal point sources along Buffalo Bayou and the Houston Ship Channel. All industries discharging to the Houston Ship Channel were required to upgrade their wastewater treatment facilities. Municipal waste treatment facilities discharging to the State of the Bay 2009 Bay the of State – tributaries of Galveston Bay were enhanced and expanded.