Making Way for Tomorrow: Benjamin and Foucault on History and Freedom Aaron Greenberg Yale University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Herbert Butterfield and the Interpretation of History (Book Review)

Volume 34 Number 3 Article 5 March 2006 Herbert Butterfield and the Interpretation of History (Book Review) Harry Van Dyke Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcollections.dordt.edu/pro_rege Recommended Citation Van Dyke, Harry (2006) "Herbert Butterfield and the Interpretation of History (Book Review)," Pro Rege: Vol. 34: No. 3, 29 - 31. Available at: https://digitalcollections.dordt.edu/pro_rege/vol34/iss3/5 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the University Publications at Digital Collections @ Dordt. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pro Rege by an authorized administrator of Digital Collections @ Dordt. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Book Review Herbert Butterfield and the Interpretation of History by Keith C. Sewell (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005) 280 pp., including bibliographies and an index. ISBN 1-4039-3928-4. $74.95. Reviewed by Harry Van Dyke, Professor of History Emeritus, Redeemer University College. Professor Keith Sewell’s bulky doctoral dissertation, prised by this conclusion? Long before the Sociology of now packaged in a manageable and attractive book of 12 Knowledge became a household word, Abraham Kuyper, lucid chapters, is an important study of a body of litera- in the great parliamentary debates of 1904, defended ture that must be considered intensely relevant for critical the inescapability of subjective interpretation and there- reflection on two areas of academic work: the science of fore the perfect validity of worldview-directed university history and the humanities in general. The book exam- studies, such as those given at the Free University, against ines successive stages in the development of the thought the charge by Leyden professor Van der Vlugt that such of Butterfield in relation to fundamental issues in the his- studies were unacceptably “sectarian.” And decades be- torical discipline. -

The Wesleyan Enlightenment

The Wesleyan Enlightenment: Closing the gap between heart religion and reason in Eighteenth Century England by Timothy Wayne Holgerson B.M.E., Oral Roberts University, 1984 M.M.E., Wichita State University, 1986 M.A., Asbury Theological Seminary, 1999 M.A., Kansas State University, 2011 AN ABSTRACT OF A DISSERTATION submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of History College of Arts and Sciences KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY Manhattan, Kansas 2017 Abstract John Wesley (1703-1791) was an Anglican priest who became the leader of Wesleyan Methodism, a renewal movement within the Church of England that began in the late 1730s. Although Wesley was not isolated from his enlightened age, historians of the Enlightenment and theologians of John Wesley have only recently begun to consider Wesley in the historical context of the Enlightenment. Therefore, the purpose of this study is to provide a comprehensive understanding of the complex relationship between a man, John Wesley, and an intellectual movement, the Enlightenment. As a comparative history, this study will analyze the juxtaposition of two historiographies, Wesley studies and Enlightenment studies. Surprisingly, Wesley scholars did not study John Wesley as an important theologian until the mid-1960s. Moreover, because social historians in the 1970s began to explore the unique ways people experienced the Enlightenment in different local, regional and national contexts, the plausibility of an English Enlightenment emerged for the first time in the early 1980s. As a result, in the late 1980s, scholars began to integrate the study of John Wesley and the Enlightenment. In other words, historians and theologians began to consider Wesley as a serious thinker in the context of an English Enlightenment that was not hostile to Christianity. -

Hume and America Donald Livingston Northern Illinois University

The Kentucky Review Volume 4 | Number 3 Article 3 Spring 1983 Hume and America Donald Livingston Northern Illinois University Follow this and additional works at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/kentucky-review Part of the Philosophy Commons Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits you. Recommended Citation Livingston, Donald (1983) "Hume and America," The Kentucky Review: Vol. 4 : No. 3 , Article 3. Available at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/kentucky-review/vol4/iss3/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Kentucky Libraries at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Kentucky Review by an authorized editor of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Hume and America Donald Livingston Of all men that distinguish themselves by memorable achievements, the first place of honour seems due to Legislators and founders of states, who transmit a system of laws and institutions to secure the peace, happiness, and liberty of future generations. -DavidHume Modern philosophy began in the seventeenth century as a reflection on the epistemological and metaphysical problems to which the new science of mathematical physics gave rise. But by the eighteenth century attention began to shift away from man as a knower of nature to man as a maker of and as an agent in civil society. By the end of the century the scientific study of social and political order was well advanced. The American Constitution was ratified in 1789 at the high tide of the Enlightenment, and the framers were and saw themselves to be thinkers who were applying the theoretical results of social and political philosophy to the practical problems of fixing the proper limits of liberty, authority, and justice. -

Order of Worship 12 20 2020

December 20, 2020 Fourth Sunday of Advent Order of Worship Welcome and Call to Worship Rev. Dr. David D. Young Prelude An Advent Prelude Charles Callahan Linda Repking - flute, Dr. Hyunju Hwang - organ Lighting of the Fourth Advent Candle Opening Sentences Michael Moorhead Scripture Genesis 12: 1-4 Bell Carol O Come, O Come, Emmanuel Neighborhood Brass Rings Prayer O God, who in this Advent season speaks again the word of blessing which calls us to new faith journeys, help us to have ears to hear and eyes to see the unfolding of your promise in the coming of Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen. Lighting of the Fourth Advent Candle We light the fourth Advent candle which points to promise as we remember father Abraham who heard God’s voice and was not afraid to take the first step in faithful response to God’s promised tomorrow. Scripture Reading Matthew 1: 18-25 Now the birth of Jesus the Messiah took place in this way. When his mother Mary had been engaged to Joseph, but before they lived together, she was found to be with child from the Holy Spirit. Her husband Joseph, being a righteous man and unwilling to expose her to public disgrace, planned to dismiss her quietly. But just when he had resolved to do this, an angel of the Lord appeared to him in a dream and said, “Joseph, son of David, do not be afraid to take Mary as your wife, for the child conceived in her is from the Holy Spirit. She will bear a son, and you are to name him Jesus, for he will save his people from their sins.” All this took place to fulfill what had been spoken by the Lord through the prophet: “Look, the virgin shall conceive and bear a son, and they shall name him Emmanuel,” which means “God is with us.” When Joseph awoke from sleep, he did as the angel of the Lord commanded him; he took her as his wife, but had no marital relations with her until she had borne a son; and he named him Jesus.” December 20, 2020 Fourth Sunday of Advent Hymn of Preparation Angels We Have Heard on High Christopher Craig, David Sateren, Dr. -

Buffy & Angel Watching Order

Start with: End with: BtVS 11 Welcome to the Hellmouth Angel 41 Deep Down BtVS 11 The Harvest Angel 41 Ground State BtVS 11 Witch Angel 41 The House Always Wins BtVS 11 Teacher's Pet Angel 41 Slouching Toward Bethlehem BtVS 12 Never Kill a Boy on the First Date Angel 42 Supersymmetry BtVS 12 The Pack Angel 42 Spin the Bottle BtVS 12 Angel Angel 42 Apocalypse, Nowish BtVS 12 I, Robot... You, Jane Angel 42 Habeas Corpses BtVS 13 The Puppet Show Angel 43 Long Day's Journey BtVS 13 Nightmares Angel 43 Awakening BtVS 13 Out of Mind, Out of Sight Angel 43 Soulless BtVS 13 Prophecy Girl Angel 44 Calvary Angel 44 Salvage BtVS 21 When She Was Bad Angel 44 Release BtVS 21 Some Assembly Required Angel 44 Orpheus BtVS 21 School Hard Angel 45 Players BtVS 21 Inca Mummy Girl Angel 45 Inside Out BtVS 22 Reptile Boy Angel 45 Shiny Happy People BtVS 22 Halloween Angel 45 The Magic Bullet BtVS 22 Lie to Me Angel 46 Sacrifice BtVS 22 The Dark Age Angel 46 Peace Out BtVS 23 What's My Line, Part One Angel 46 Home BtVS 23 What's My Line, Part Two BtVS 23 Ted BtVS 71 Lessons BtVS 23 Bad Eggs BtVS 71 Beneath You BtVS 24 Surprise BtVS 71 Same Time, Same Place BtVS 24 Innocence BtVS 71 Help BtVS 24 Phases BtVS 72 Selfless BtVS 24 Bewitched, Bothered and Bewildered BtVS 72 Him BtVS 25 Passion BtVS 72 Conversations with Dead People BtVS 25 Killed by Death BtVS 72 Sleeper BtVS 25 I Only Have Eyes for You BtVS 73 Never Leave Me BtVS 25 Go Fish BtVS 73 Bring on the Night BtVS 26 Becoming, Part One BtVS 73 Showtime BtVS 26 Becoming, Part Two BtVS 74 Potential BtVS 74 -

Friday, 9/25/20 Announcements • the Jesuit's Dads Club Is Sponsoring A

Friday, 9/25/20 Announcements • The Jesuit’s Dads Club is sponsoring a Feeding Tampa Bay Mobile Pantry on Saturday, October 3rd at Hillsborough Community College. This is an opportunity for Jesuit students to volunteer alongside their fathers to help serve the hungry throughout the Tampa Bay area. The Dad’s Club is looking for 50-75 father-son pairs to help make this event a success. Interested volunteers should check the X2Vol bulletin board or email Coach Wood with any questions. • Auditions for The Masque’s fall production TWELVE INCOMPETENT JURORS will take place via Zoom today and Monday at 4pm. It is not too late to sign up, and no prior acting experience is required. To register, see the Masque Fall Play Auditions module on the Student Life Canvas page. • Yesterday, the Tiger Golf team, led by Carter Dill and Chase Johns, defeated Tampa Catholic by sweeping the Crusaders in what was their final meeting this season. Next up, the team will participate in The Lakewood Ranch Invitational on Monday. • Yesterday, the Jesuit Swimming and Diving team moved to 3-0 on the season by defeating Robinson, 145-26. Winners included: -200 Medley Relay: Liam Schindler, Nick Shaffer, Jordan Jansen, Sam Prabhakaran -200 Freestyle: Ryan Finster -200 IM: Sam Prabhakaran -50 Freestyle: Nick Shaffer -Diving: Sasha Fiola -100 Fly: Brayden Hohman -100 Freestyle: Jordan Jansen -500 Freestyle: Nick Shaffer -200 Freestyle Relay: Sam Prabhakaran, Ryan Finster, Sean Kenny, Erick Magalhaes -100 Backstroke: Aidan Clements -100 Breaststroke: Sam Prabhakaran -400 Freestyle Relay: Brayden Hohman, Liam Schindler, Jordan Jansen, Nick Shaffer The team looks to continue their dominance next Tuesday against Plant. -

The Vision Thing”: George H.W

“The Vision Thing”: George H.W. Bush and the Battle For American Conservatism 19881992 Paul Wilson A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of BACHELOR OF ARTS WITH HONORS DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN April 1, 2012 Advised by Professor Maris Vinovskis For my Grandfather, who financed this project (and my education). For my beautiful Bryana, who encouraged me every step of the way. Introduction............................................................................................................................................. 6 Chapter One: The Clash of Legacies.......................................................................................... 14 Chapter Two: The End of the Cold War and the New European Order ................ 42 Chapter Three: 1992 and the Making of Modern American Conservatism....... 70 Conclusion............................................................................................................................................ 108 Bibliography....................................................................................................................................... 114 4 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Many thanks to the University of Michigan library system for providing access to the material used in the making of this thesis. Thanks to Professor Maris Vinovskis, who provided invaluable knowledge and mentorship throughout the whole writing process. Much gratitude goes to Dr. Sigrid Cordell, who always found the resources I needed to complete this -

Normativity and Objectivity in Historical Writing (My Dinner with Schlegel)

Buffalo Law Review Volume 69 Number 1 Serious Fun: A conference with & Article 8 around Schlegel! 1-11-2021 Normativity and Objectivity in Historical Writing (My Dinner with Schlegel) Matt Steilen University at Buffalo School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.buffalo.edu/buffalolawreview Part of the Legal Education Commons Recommended Citation Matt Steilen, Normativity and Objectivity in Historical Writing (My Dinner with Schlegel), 69 Buff. L. Rev. 133 (2021). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.buffalo.edu/buffalolawreview/vol69/iss1/8 This Symposium Essay is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at Digital Commons @ University at Buffalo School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Buffalo Law Review by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ University at Buffalo School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Buffalo Law Review VOLUME 69 JANUARY 2021 NUMBER 1 Normativity and Objectivity in Historical Writing (My Dinner with Schlegel) MATT STEILEN† Dear friends do not provide the best material for reflection. One’s nearness to them interferes in ways that are usually undetectable until too late. Peculiar friends, in contrast, require a labor of constant reflection. Why on earth does he act that way? This Essay is for my dear and peculiar friend, Jack Schlegel. It grows out of some readings we did together before the pandemic and before the unrest that followed the killing of George Floyd, a time that now feels like an age ago. The subject was historiography and our syllabus included Acton, Beard, Butterfield, Bloch, Carr, a packaged introduction to the philosophy of history by R. -

Works by Herbert Butterfield, Unless Otherwise Stated

Notes Note: All references are to works by Herbert Butterfield, unless otherwise stated. Introduction 1. 'Paul Vellacott: Master of Peterhouse, 1939-1954', The Sex 114 Oune 1956), 1-4. For Vellacott's style, see his 'The Diary of a Country Gentleman in 1688', CHJ 2 (1926-28), 48-62. 2. 'George Peabody Gooch', The Contemporary Review 200 (1961), 501-5, esp. 502. Cf. Frank Eyck, G. P. Gooch: A Study in History and Politics (1982), esp. pp. 311-405; John D. Fair, Harold Temperley: A Scholar and Romantic in the Public Realm (1992), esp. pp. 167-215; SMH, pp. 4-6; and 'Harold Temperley and George Canning', in H. W. V. Temperley, The Foreign Policy of Canning 1822-1827 (1966), p. viii. 3. C. Thomas Mcintire, 'Introduction Herbert Butterfield on Christianity and History', WCH, pp. xxiv-xxv. 4. SM, pp. 40, 45, 71-2, review of Symondson, EHR 87 (1972), 644; and DHI I, p. 403. Cf. C. Thomas Mcintire, 'Introduction Herbert Butterfield on Christianity and History', WCH, pp. xxv-xxvi. 5. 'Early Youth', BP, 7. Cf. Adolf Harnack, Christianity and History (1898); What is Christianity? (1901). 6. John L. Clive, 'The Prying Yorkshireman', New Republic 186 (23 June 1982), 31. 7. EH, pp. 88-90; GNP, pp. 196-206; and GH, pp. 220-4. 8. ' History as the Organisation of Man's Memory', in Knowledge Among Men, ed. Paul H. Oehser, (1966), p. 31. 9. For Butterfield on his writings, see 'My Literary Productions', BP, 269/3. 10. Review of Carr, CR 83 (2 December 1961), 172. 11. CH, pp. -

Fallen Angels: the Investment Opportunity

Fallen Angels: The investment opportunity Authors: Prof. Andrew Clare, Prof. Stephen Thomas, Dr. Nick Motson This document is for Professional Clients only in Dubai, Jersey, Guernsey, the Isle of Man and the UK, Professional Clients and Financial Advisers in Continental Europe and Qualifi ed Investors in Switzerland and is not for consumer use. Centre for Asset Management Research Cass Business School in cooperation with Invesco PowerShares September 2016 Table of content 1 What is a fallen angel? 3 2 What’s the potential investment opportunity? 3 - 4 2.1 The overreaction hypothesis 2.2 Institutional factors 2.3 Summary 3 Evidence of the impact on bond prices 4 - 8 4 How could investing in this idea fit into a portfolio? 8 - 10 5 Summary 10 References • Barron, M., A. Clare and S.H. Thomas, The information content of credit rating changes in the UK stock market, The Journal of Business Finance and Accounting, (1997), Vol. 24, 497-509. • Cantor, R., O. Ap Gwilym and S.H. Thomas, The Use of Credit Ratings in Investment Management in the U.S. and Europe, The Journal of Fixed Income, (Fall 2007), Vol. 17, No. 2: 13-26. • Clare, A. and S.H. Thomas, Winners and losers: UK evidence for the overreaction hypothesis, The Journal of Business Finance and Accounting, (October 1995), 961-973. • DeBondt, W.F.M. and R.H. Thaler (1985), Does the stock market overreact? Journal of Finance, Vol. 40, 793-805. • Hite, G. and A. Warga, The Effect of Bond-Rating Changes on Bond Price Performance, Financial Analysts Journal, Vol. -

29 from the Library of Professor Richard B. Dinsmore, Phd FY2006

From the Library of Professor Richard B. Dinsmore, PhD FY2006 1848 : The Revolutionary Tide in Europe / Peter N. Stearns 500 Popular Annuals and Perennials for American Gardeners / Edited by Loretta Barnard About Philosophy / Robert Paul Wolff Absolutism and Enlightenment, 1660-1789 / R. W. Harris Action Française; Royalism and Reaction in Twentieth-Century France Action Française; Die-Hard Reactionaries in Twentieth-Century France Adding on / Editors of Time-Life Books Advanced Woodworking / Editors of Time-Life Books After Everything : Western Intellectual History Since 1945 / Roland N. Stromberg Age of Louis XIV Age of Nationalism and Reform, 1850-1890 Age of Revolution and Reaction, 1789-1850 Age of the Economist / Daniel R. Fusfeld Age of Controversy: Discussion Problems in 20th Century European History / Gordon Wright Alexander the Great : Legacy of a Conqueror / Winthrop Lindsay Adams All Quiet on the Western Front / Erich Maria Remarque All About Market Timing : The Easy Way to Get Started / Leslie N. Masonson An Intellectual History of Modern Europe / Roland N. Stromberg Ancien Régime; French Society 1600-1750. Translated by Steve Cox Ancien Régime / Hubert Méthivier Ancient Near Eastern Tradition Ancient World Ancient Near East Anticlericalism; Conflict Between Church & State in France, Italy, and Spain / J. S. Schapiro Antony and Cleopatra / Louis B. Wright and Virginia Lamar Army of the Republic, 1871-1914 / David B. Ralston Art of Cross-Examination / Francis L. Wellman Artisans and Sans-culottes; Popular Movements in France and Britain... / Gwyn A. Williams Aspects of Western Civilization : Problems and Sources in History / Edited by Perry M. Rogers Aspects of Western Civilization : Problems and Sources in History / Edited by Perry M. -

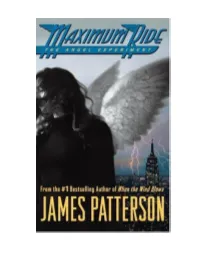

Maximum Ride T H E ANGEL EXPERIMENT

Maximum Ride T H E ANGEL EXPERIMENT James Patterson WARNER BOOKS NEW YORK BOSTON Copyright © 2005 by Suejack, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a review. Warner Vision and the Warner Vision logo are registered trademarks of Time Warner Book Group Inc. Time Warner Book Group 1271 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020 Visit our Web site at www.twbookmark.com First Mass Market Edition: May 2006 First published in hardcover by Little, Brown and Company in April 2005 The characters and events portrayed in this book are fictitious. Any similarity to real persons, living or dead, is coincidental and not intended by the author. Cover design by Gail Doobinin Cover image of girl © Kamil Vojnar/Photonica, city © Roger Wood/Corbis Logo design by Jon Valk Produced in cooperation with Alloy Entertainment Library of Congress Cataloguing-in-Publication Data Maximum Ride : the angel experiment / by James Patterson. — 1st ed. p.cm. Summary: After the mutant Erasers abduct the youngest member of their group, the "bird kids," who are the result of genetic experimentation, take off in pursuit and find themselves struggling to understand their own origins and purpose. ISBN: 0-316-15556-X(HC) ISBN: 0-446-61779-2 (MM) [1. Genetic engineering — Fiction. 2. Adventure and adventurers — Fiction.] 1. Title. 10 9876543 2 1 Q-BF Printed in the United States of America For Jennifer Rudolph Walsh; Hadley, Griffin, and Wyatt Zangwill Gabrielle Charbonnet; Monina and Piera Varela Suzie and Jack MaryEllen and Andrew Carole, Brigid, and Meredith Fly, babies, fly! To the reader: The idea for Maximum Ride comes from earlier books of mine called When the Wind Blows and The Lake House, which also feature a character named Max who escapes from a quite despicable School.