The Vision Thing”: George H.W

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

George Bush and the End of the Cold War. Christopher Alan Maynard Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 2001 From the Shadow of Reagan: George Bush and the End of the Cold War. Christopher Alan Maynard Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Maynard, Christopher Alan, "From the Shadow of Reagan: George Bush and the End of the Cold War." (2001). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 297. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/297 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI fiims the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction.. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

Election Division Presidential Electors Faqs and Roster of Electors, 1816

Election Division Presidential Electors FAQ Q1: How many presidential electors does Indiana have? What determines this number? Indiana currently has 11 presidential electors. Article 2, Section 1, Clause 2 of the Constitution of the United States provides that each state shall appoint a number of electors equal to the number of Senators or Representatives to which the state is entitled in Congress. Since Indiana has currently has 9 U.S. Representatives and 2 U.S. Senators, the state is entitled to 11 electors. Q2: What are the requirements to serve as a presidential elector in Indiana? The requirements are set forth in the Constitution of the United States. Article 2, Section 1, Clause 2 provides that "no Senator or Representative, or person holding an Office of Trust or Profit under the United States, shall be appointed an Elector." Section 3 of the Fourteenth Amendment also states that "No person shall be... elector of President or Vice-President... who, having previously taken an oath... to support the Constitution of the United States, shall have engaged in insurrection or rebellion against the same, or given aid or comfort to the enemies thereof. Congress may be a vote of two-thirds of each House, remove such disability." These requirements are included in state law at Indiana Code 3-8-1-6(b). Q3: How does a person become a candidate to be chosen as a presidential elector in Indiana? Three political parties (Democratic, Libertarian, and Republican) have their presidential and vice- presidential candidates placed on Indiana ballots after their party's national convention. -

George HW Bush and CHIREP at the UN 1970-1971

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations Dissertations and Theses Spring 5-22-2020 The First Cut is the Deepest: George H.W. Bush and CHIREP at the U.N. 1970-1971 James W. Weber Jr. University of New Orleans, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td Part of the American Popular Culture Commons, Asian History Commons, Cultural History Commons, Diplomatic History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Weber, James W. Jr., "The First Cut is the Deepest: George H.W. Bush and CHIREP at the U.N. 1970-1971" (2020). University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations. 2756. https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td/2756 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by ScholarWorks@UNO with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The First Cut is the Deepest : George H.W. Bush and CHIREP at the U.N. 1970–1971 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of New Orleans in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History by James W. -

The Evolution of Neo-Conservative Foreign Policy Agenda - from the Cold War to the New Millennium Selected Issues

AD AMERICAM Journal of American Studies Vol. 8, 2008 ISSN 1896-9461 ISBN 978-83-233-2533-8 Grzegorz Nycz THE EVOLUTION OF NEO-CONSERVATIVE FOREIGN POLICY AGENDA - FROM THE COLD WAR TO THE NEW MILLENNIUM SELECTED ISSUES I. THE ORIGINS 1. The history of American neo-conservatism begins in the 1960s with a group of in tellectuals from the liberal camp, who rejected the Cultural Revolution and the radi calism of the New Left. The intellectual leaders of the new movement, Norman Pod- horetz and Irving Kristol, as well as their allies and associates Nathan Glazer, Daniel Bell, Daniel Patrick Moynihan and Jeanne Kirkpatrick, among others, were later named “neo-conservatives” or “neocons” to emphasize the difference between “converted” leftist liberals and “regular” republican conservatives (Ehrman 2000: 50- -70). Notably, neo-conservatives formed their intellectual credo from the elements of many doctrines - including the thought of Hannah Arendt, Reinhold Niebuhr, Walter Lippman, Arthur Schlesinger Jr., and Leo Strauss. In general, they shared the view of the whole conservative camp, that the social crisis of the 1960s and 1970s was deep ened by the counterculture, which undermined the Judeo-Christian tradition in America and infected the roots of American society. The “regular” and “neo” conser vatives commonly believed that American society had been weakened by the effects of industrialization and suffered from the erosion of social relations, caused by the leftist-liberal campaign against religion and family. In matters of foreign policy the early neo-conservatives defended containment and anticommunism, strongly sup ported the alliance between America and Israel and raised the significance of moral issues in international policy (Podhoretz 1986, Kristol 1999, Ehrman 2000, Friedman 2005, Tokarski 2006). -

The Impact of the New Right on the Reagan Administration

LONDON SCHOOL OF ECONOMICS UNIVERSITY OF LONDON THE IMPACT OF THE NEW RIGHT ON THE REAGAN ADMINISTRATION: KIRKPATRICK & UNESCO AS. A TEST CASE BY Isaac Izy Kfir LONDON 1998 UMI Number: U148638 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U148638 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 2 ABSTRACT The aim of this research is to investigate whether the Reagan administration was influenced by ‘New Right’ ideas. Foreign policy issues were chosen as test cases because the presidency has more power in this area which is why it could promote an aggressive stance toward the United Nations and encourage withdrawal from UNESCO with little impunity. Chapter 1 deals with American society after 1945. It shows how the ground was set for the rise of Reagan and the New Right as America moved from a strong affinity with New Deal liberalism to a new form of conservatism, which the New Right and Reagan epitomised. Chapter 2 analyses the New Right as a coalition of three distinctive groups: anti-liberals, New Christian Right, and neoconservatives. -

Picking the Vice President

Picking the Vice President Elaine C. Kamarck Brookings Institution Press Washington, D.C. Contents Introduction 4 1 The Balancing Model 6 The Vice Presidency as an “Arranged Marriage” 2 Breaking the Mold 14 From Arranged Marriages to Love Matches 3 The Partnership Model in Action 20 Al Gore Dick Cheney Joe Biden 4 Conclusion 33 Copyright 36 Introduction Throughout history, the vice president has been a pretty forlorn character, not unlike the fictional vice president Julia Louis-Dreyfus plays in the HBO seriesVEEP . In the first episode, Vice President Selina Meyer keeps asking her secretary whether the president has called. He hasn’t. She then walks into a U.S. senator’s office and asks of her old colleague, “What have I been missing here?” Without looking up from her computer, the senator responds, “Power.” Until recently, vice presidents were not very interesting nor was the relationship between presidents and their vice presidents very consequential—and for good reason. Historically, vice presidents have been understudies, have often been disliked or even despised by the president they served, and have been used by political parties, derided by journalists, and ridiculed by the public. The job of vice president has been so peripheral that VPs themselves have even made fun of the office. That’s because from the beginning of the nineteenth century until the last decade of the twentieth century, most vice presidents were chosen to “balance” the ticket. The balance in question could be geographic—a northern presidential candidate like John F. Kennedy of Massachusetts picked a southerner like Lyndon B. -

("DSCC") Files This Complaint Seeking an Immediate Investigation by the 7

COMPLAINT BEFORE THE FEDERAL ELECTION CBHMISSIOAl INTRODUCTXON - 1 The Democratic Senatorial Campaign Committee ("DSCC") 7-_. J _j. c files this complaint seeking an immediate investigation by the 7 c; a > Federal Election Commission into the illegal spending A* practices of the National Republican Senatorial Campaign Committee (WRSCIt). As the public record shows, and an investigation will confirm, the NRSC and a series of ostensibly nonprofit, nonpartisan groups have undertaken a significant and sustained effort to funnel "soft money101 into federal elections in violation of the Federal Election Campaign Act of 1971, as amended or "the Act"), 2 U.S.C. 5s 431 et seq., and the Federal Election Commission (peFECt)Regulations, 11 C.F.R. 85 100.1 & sea. 'The term "aoft money" as ueed in this Complaint means funds,that would not be lawful for use in connection with any federal election (e.g., corporate or labor organization treasury funds, contributions in excess of the relevant contribution limit for federal elections). THE FACTS IN TBIS CABE On November 24, 1992, the state of Georgia held a unique runoff election for the office of United States Senator. Georgia law provided for a runoff if no candidate in the regularly scheduled November 3 general election received in excess of 50 percent of the vote. The 1992 runoff in Georg a was a hotly contested race between the Democratic incumbent Wyche Fowler, and his Republican opponent, Paul Coverdell. The Republicans presented this election as a %ust-win81 election. Exhibit 1. The Republicans were so intent on victory that Senator Dole announced he was willing to give up his seat on the Senate Agriculture Committee for Coverdell, if necessary. -

Anti-Americanism and the Rise of World Opinion: Consequences for the US National Interest Monti Narayan Datta Index More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-03232-3 - Anti-Americanism and the Rise of World Opinion: Consequences for the US National Interest Monti Narayan Datta Index More information Index Adidas-Salomon legitimacy of 45, 57, 80 comparative consumer study 84–9 and overseas image 191–3 European sales 88 and public diplomacy 191–3 Afghanistan relaxation 4 American foreign policy 4 and tourism 3–4 ISAF (International Security Assistance and unilateralism 3, 8–9, 36–7 Force) 4, 160–70 and world opinion 191 Obama effect on war 159–70 American national interest support for United States 20, 159–63 and anti-Americanism 13–15 troop contributions to ISAF 164–8 and decision-makers 13 troops variable 162–70 measurement of 13–14 alliance variable 64, 72, 77, 80, 133–7 policy objectives in 13–14 America American overseas wars, support for attention to interests of other countries 15–17, 146–7 see also coalition 35 support; First Gulf War (1991); Iraq credit rating 182 war (2003) culture, and anti-Americanism 3, 6, 10, American unipolarity/multipolarity 37–8, 112–14 175, 187 declining world status 181–3 American voters 23 economic power 185 analytic framework description 15–18 exceptionalism 45–6 anti-Bushism, 131–2, 149 see also Bush favorable opinions toward 62, 152, anti-great powerism 187–90 194–229 Arab public opinion 26–7 financial status 182–3 Arab Street 26 Gulf wars costs 119–26 Argentina higher education 108, 185–7 on Iraq war 145–6 innovation, and economic strength 185 on Obama effect 172 military spending 185 Armitage, Richard 57 multilateralism -

Case 2:07-Cv-03053-JTM-ALC Document 69 Filed 08/11/09 Page 1 of 23

Case 2:07-cv-03053-JTM-ALC Document 69 Filed 08/11/09 Page 1 of 23 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT EASTERN DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA ST. PAUL FIRE AND MARINE INSURANCE CIVIL ACTION COMPANY, ET AL. VERSUS No. 07-3053 BOARD OF COMMISSIONERS OF THE PORT SECTION: I/5 OF NEW ORLEANS ORDER AND REASONS Before the Court is a motion for summary judgment filed by plaintiffs, St. Paul Fire and Marine Insurance Company, Insurance Company of North America and American Home Assurance Company (collectively “the Underwriters”). For the following reasons, the motion is GRANTED IN PART AND DENIED IN PART.1 BACKGROUND This action for declaratory judgment arises in connection with a state court judgment awarding John Morella (“Morella”) and his wife damages for injuries sustained in a July, 2001 accident on property owned by defendant, the Board of Commissioners of the Port of New Orleans (“the Board”). In 2002, Morella filed a lawsuit against the Board in state court alleging that he was driving a top loader when his vehicle fell into a pothole, causing 1In a telephone conference with the Court, the parties confirmed that they had no objections to the admissibility of any evidence submitted in connection with this motion. Rec. Doc. No. 64. 1 Case 2:07-cv-03053-JTM-ALC Document 69 Filed 08/11/09 Page 2 of 23 him injuries.2 The state court tried the case without a jury on January 16, 2007, and on February 28, 2007, the state court entered a $2.6 million judgment in favor of Morella and a $50,000 judgment in favor of his wife on her loss of consortium claim.3 Following a motion for new trial, the state court entered an amended judgment on March 23, 2007, awarding interest at a rate of six percent from the date of judicial demand.4 The Louisiana Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals affirmed the judgment on May 14, 2008.5 Morella v. -

TEACHER's Guide

TEACHER'S GUIDE 1 WEEK 1 ANSWERS: North Platte, becoming simply the Platte of the boundary between Nevada and River; the Platte eventually empties into Arizona and California and Arizona. Of 1.Idaho, Wyoming, Colorado, and the Missouri River. these, only Colorado is a Big 12 state. Oklahoma. Some may travel through The river eventually flows into Mexico and Idaho, Wyoming, Nebraska, Kansas, and (b)The Arkansas River flows from empties into the Gulf of California. The Oklahoma. Colorado, through Kansas and Oklahoma. other Colorado River is located entirely It then flows into Arkansas (not a Big 12 within the state of Texas, eventually 2. Texas A & M state) and eventually empties into the emptying into the Gulf of Mexico. Mississippi River. 3. Denver is the capital and the University 5.Manhattan (Kansas State) and of Colorado is closer. (c)There are actually two Colorado Rivers Lawrence (Kansas) are about 80 miles in the United States! The larger of the two apart. 4. (a)The South Platte River flows from starts in Colorado and flows west through Colorado into Nebraska, where it joins the Utah and Arizona before becoming part 2 WEEK 2 ANSWERS: Central, Mountain, and Pacific. In the 19th Cane River Creole National Historical Park 1 Historic Route 66. century, railroad companies established the in Louisiana; Hot Springs National Park and time zones in the United States in order to help Fort Smith National Historic Site in Arkansas; 2.The Louisiana Tech—Texas A&M game will people board trains on time. and the Chickasaw National Recreation Area be played at Kyle Field in College Station, and the Oklahoma City National Memorial in Texas where the elevation is 364 feet above 4.International cities with similar longitudes Oklahoma. -

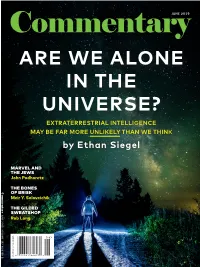

John Podhoretz

CommentaryJUNE 2019 ARE WE ALONE IN THE UNIVERSE? EXTRATERRESTRIAL INTELLIGENCE MAY BE FAR MORE UNLIKELY THAN WE THINK by Ethan Siegel MARVEL AND THE JEWS John Podhoretz THE BONES Commentary OF BRISK Meir Y. Soloveichik THE GILDED JUNE 2019 : VOLUME 147 NUMBER 6 147 : VOLUME JUNE 2019 SWEATSHOP Rob Long $5.95 US : $7.00 CANADA $7.00 : US $5.95 JUNE 2019 COVER.indd 1 5/13/19 3:58 PM Acts of terror injure hundreds of Israelis. One act from you can save thousands. In Israel, only one agency is the official ambulance, disaster-response, and blood-services agency for the nation’s 9 million people. Yet, it’s not funded by the government. When you support Magen David Adom, you get the satisfaction of knowing your gift has impact. If you value life and want to make Israel a stronger, safer place, there’s no greater way than by supporting Magen David Adom. Save a life in Israel. Support Magen David Adom at afmda.org/one-act or call 866.632.2763. JUNE 2019 COVER.indd 2 5/13/19 3:57 PM EDITOR’S COMMENTARY The Human Miracle JOHN PODHORETZ UR EARTH WOULD BE so much better if it I think this notion has something to do with the didn’t have people, wouldn’t it? That notion— environmentalist downgrade of humanity over the past Owhat you might call a view of original sin ab- half century. Some of us can believe humanity is beyond sent possibility of redemption—is the hidden backbone salvation and the world would be better without it be- of radical environmentalism. -

Christ's Heavenly Sanctuary Ministry

Perspective Digest Volume 15 Issue 3 Summer Article 7 2010 Christ's Heavenly Sanctuary Ministry Roy Gane Andrews University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/pd Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, Christian Denominations and Sects Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Gane, Roy (2010) "Christ's Heavenly Sanctuary Ministry," Perspective Digest: Vol. 15 : Iss. 3 , Article 7. Available at: https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/pd/vol15/iss3/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Adventist Theological Society at Digital Commons @ Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Perspective Digest by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Gane: Christ's Heavenly Sanctuary Ministry BY ROY E. GANE* CHRIST’S HEAVENLY SANCTUARY MINISTRY ART 5 The Adventist understanding of the heavenly sanctuary pertains to the church’s one unique contribution to theology. he fifth core belief affirmed by historicist interpretive approach, the Adventist Theological So- including recog nition of the year- ciety (ATS) as a teaching of day principle, which makes it possi- T Scripture and of the Seventh- ble to identify 1844 A.D. as the date day Adventist Church is as when the pre-advent judgment follows: “I affirm a real sanctuary in began. heaven and the pre-advent judg- ment of believers beginning in 1844, based upon the historicist *Roy Gane, Ph.D., is Professor of He- view of prophecy and the year-day brew Bible and Ancient Near Eastern principle as taught in Scripture.” Languages, and Director of the Ph.D.