Understanding China's Response to Ethnic Conflicts in Myanmar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fund for HIV/AIDS in Myanmar UNAIDS

Annual Progress Report, 1 Apr 2006 - 31 Mar 2007 Table of Contents Foreword 3 About this report 5 Highlights in Achievements 7 Progress and Achievements 9 ....... Access to services to prevent the sexual transmission of HIV improved 9 ....... Access to services to prevent transmission of HIV in injecting drug use ....... improved 18 ....... Knowledge and attitudes improved 27 ....... Access to services for HIV care and support improved 30 Fund Management 41 ....... Programmatic and Financial Monitoring 41 ....... Financial Status and Utilisation of Funds 43 Operating Environment 44 Annexe 1: Implementing Partners expenditure and budgets 45 Annexe 2: Summary of Technical Progress Apr 2004–Mar 2007 49 Annexe 3: Achievements by Implementing Partners Round II, II(b) 50 Annexe 4: Guiding principles for the provision of humanitarian assistance 57 Acronyms and abbreviations 58 1 Fund for HIV/AIDS in Myanmar UNAIDS 2 Annual Progress Report, 1 Apr 2006 - 31 Mar 2007 Foreword This report will be the last for the Fund for HIV/AIDS in Myanmar (FHAM), covering its fourth and final year of operation (the fiscal year from April 2006 through March 2007). Created as a pooled funding mechanism in 2003 to support the United Nations Joint Programme on AIDS in Myanmar, the FHAM has demonstrated that international resources can be used to finance HIV services for people in need in an accountable and transparent manner. As this report details, progress has been made in nearly every area of HIV prevention – especially among the most at-risk groups related to sex work and drug use – and in terms of care and support, including anti-retroviral treatment. -

Gold Mining in Shwegyin Township, Pegu Division (Earthrights International)

Accessible Alternatives Ethnic Communities’ Contribution to Social Development and Environmental Conservation in Burma Burma Environmental Working Group September 2009 CONTENTS Acknowledgments ......................................................................................... iii About BEWG ................................................................................................. iii Executive Summary ...................................................................................... v Notes on Place Names and Currency .......................................................... vii Burma Map & Case Study Areas ................................................................. viii Introduction ................................................................................................... 1 Arakan State Cut into the Ground: The Destruction of Mangroves and its Impacts on Local Coastal Communities (Network for Environmental and Economic Development - Burma) ................................................................. 2 Traditional Oil Drillers Threatened by China’s Oil Exploration (Arakan Oil Watch) ........................................................................................ 14 Kachin State Kachin Herbal Medicine Initiative: Creating Opportunities for Conservation and Income Generation (Pan Kachin Development Society) ........................ 33 The Role of Kachin People in the Hugawng Valley Tiger Reserve (Kachin Development Networking Group) ................................................... 44 Karen -

There Is More Than 3TG the Need for the Inclusion of All Minerals in EU Regulation for Conflict Due Diligence

There is more than 3TG The need for the inclusion of all minerals in EU regulation for conflict due diligence SOMO Paper | January 2015 Companies that use minerals in their products risk International standards and regulation contributing to conflict financing or human rights abuses via their mineral supply chains, especially if upstream Normative standards suppliers are located in conflict zones. This problem is Under the European Convention on Human Rights and being addressed by the European Commission (EC), international human rights law, European member states which has proposed a new regulation with a voluntary have an obligation to ensure that business enterprises due diligence framework to address the risk of financing operating within their jurisdiction do not cause or armed groups and security forces, and mitigate other contribute to human rights violations. The United Nations adverse impacts associated with the extraction, transport Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGP) and trade of four particular minerals: tin, tantalum, and the Organisation for Economic Development and tungsten and gold (3TG). Cooperation’s Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises (OECD Guidelines) set clear standards for business enter- This briefing paper discusses one specific issue in the prises to respect human rights, conduct human rights due proposed EC regulation – the limited number of conflict diligence and implement measures to prevent, address and minerals it includes. It puts the case that the decision to redress any human rights violations.1 The UNGP prescribe focus on the import of minerals and metals containing or that states need to “ensure that their current policies, consisting of 3TG is arbitrary and far too limited to achieve legislation, regulations and enforcement measures are the proposal’s objective of reducing the financing of armed effective in addressing the risks of business involvement groups and security forces through mineral proceeds in in gross human rights abuses”.2 The UNGP have special conflict-affected and high-risk areas. -

Identity Crisis: Ethnicity and Conflict in Myanmar

Identity Crisis: Ethnicity and Conflict in Myanmar Asia Report N°312 | 28 August 2020 Headquarters International Crisis Group Avenue Louise 235 • 1050 Brussels, Belgium Tel: +32 2 502 90 38 • Fax: +32 2 502 50 38 [email protected] Preventing War. Shaping Peace. Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. A Legacy of Division ......................................................................................................... 4 A. Who Lives in Myanmar? ............................................................................................ 4 B. Those Who Belong and Those Who Don’t ................................................................. 5 C. Contemporary Ramifications..................................................................................... 7 III. Liberalisation and Ethno-nationalism ............................................................................. 9 IV. The Militarisation of Ethnicity ......................................................................................... 13 A. The Rise and Fall of the Kaungkha Militia ................................................................ 14 B. The Shanni: A New Ethnic Armed Group ................................................................. 18 C. An Uncertain Fate for Upland People in Rakhine -

Burma's Long Road to Democracy

UNITED STATES InsTITUTE OF PEACE www.usip.org SPECIAL REPORT 1200 17th Street NW • Washington, DC 20036 • 202.457.1700 • fax 202.429.6063 ABOUT THE REPORT Priscilla Clapp A career officer in the U.S. Foreign Service, Priscilla Clapp served as U.S. chargé d’affaires and chief of mission in Burma (Myanmar) from June 1999 to August 2002. After retiring from the Foreign Service, she has continued to Burma’s Long Road follow events in Burma closely and wrote a paper for the United States Institute of Peace entitled “Building Democracy in Burma,” published on the Institute’s Web site in July 2007 as Working Paper 2. In this Special to Democracy Report, the author draws heavily on her Working Paper to establish the historical context for the Saffron Revolution, explain the persistence of military rule in Burma, Summary and speculate on the country’s prospects for political transition to democracy. For more detail, particularly on • In August and September 2007, nearly twenty years after the 1988 popular uprising the task of building the institutions for stable democracy in Burma, public anger at the government’s economic policies once again spilled in Burma, see Working Paper 2 at www.usip.org. This into the country’s city streets in the form of mass protests. When tens of thousands project was directed by Eugene Martin, and sponsored by of Buddhist monks joined the protests, the military regime reacted with brute force, the Institute’s Center for Conflict Analysis and Prevention. beating, killing, and jailing thousands of people. Although the Saffron Revolution was put down, the regime still faces serious opposition and unrest. -

Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State

A Return to War: Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State ASIA PAPER May 2018 EUROPEAN UNION A Return to War: Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State © Institute for Security and Development Policy V. Finnbodavägen 2, Stockholm-Nacka, Sweden www.isdp.eu “A Return to War: Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State” is an Asia Paper published by the published by the Institute for Security and Development Policy. The Asia Paper Series is the Occasional Paper series of the Institute’s Asia Program, and addresses topical and timely subjects. The Institute is based in Stockholm, Sweden, and cooperates closely with research centers worldwide. The Institute serves a large and diverse community of analysts, scholars, policy-watchers, business leaders, and journalists. It is at the forefront of research on issues of conflict, security, and development. Through its applied research, publications, research cooperation, public lectures, and seminars, it functions as a focal point for academic, policy, and public discussion. This publication has been produced with funding by the European Union. The content of this publication does not reflect the official opinion of the European Union. Responsibility for the information and views expressed in the paper lies entirely with the authors. No third-party textual or artistic material is included in the publication without the copyright holder’s prior consent to further dissemination by other third parties. Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. © European Union and ISDP, 2018 Printed in Lithuania ISBN: 978-91-88551-11-5 Cover photo: Patrick Brown patrickbrownphoto.com Distributed in Europe by: Institute for Security and Development Policy Västra Finnbodavägen 2, 131 30 Stockholm-Nacka, Sweden Tel. -

Social Reproduction and Migrant Education: a Critical Sociolinguistic Ethnography of Burmese Students’ Learning Experiences at a Border High School in China

Department of Linguistics Faculty of Human Sciences Social Reproduction and Migrant Education: A Critical Sociolinguistic Ethnography of Burmese Students’ Learning Experiences at a Border High School in China By Jia Li (李佳) This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy November 2016 i Table of Contents Abstract ........................................................................................................................ viii Statement of Candidate ................................................................................................... x Acknowledgements ....................................................................................................... xi List of Figures .............................................................................................................. xvi List of Tables .............................................................................................................. xvii List of Abbreviations and Acronyms ........................................................................xviii Glossary of Burmese and Chinese terms ..................................................................... xix Chapter One: Introduction .............................................................................................. 1 1.1 Research problem ................................................................................................. 1 1.2 Introducing the research context at the China-and-Myanmar border ................... 4 1.3 China’s rise and Chinese language -

Mong La: Business As Usual in the China-Myanmar Borderlands

Mong La: Business as Usual in the China-Myanmar Borderlands Alessandro Rippa, Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich Martin Saxer, Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich The aim of this project is to lay the conceptual groundwork for a new understanding of the positionality of remote areas around the globe. It rests on the hypothesis that remoteness and connectivity are not independent features but co-constitute each other in particular ways. In the context of this project, Rippa and Saxer conducted exploratory fieldwork together in 2015 along the China-Myanmar border. This collaborative photo essay is one result of their research. They aim to convey an image of Mong La that goes beyond its usual depiction as a place of vice and unruliness, presenting it, instead, as the outcome of a particular China-inspired vision of development. Infamous Mong La It is 6:00 P.M. at the main market of Mong La, the largest town in the small autonomous strip of land on the Chinese border formally known in Myanmar as Special Region 4. A gambler from China’s northern Heilongjiang Province just woke up from a nap. “I’ve been gambling all morning,” he says, “but after a few hours it is better to stop. To rest your brain.” He will go back to the casino after dinner, as he did for the entire month he spent in Mong La. Like him, hundreds of gamblers crowd the market, where open-air restaurants offer food from all over China. A small section of the market is dedicated to Mong La’s most infamous commodity— wildlife. -

Political Monitor No.7

Euro-Burma Office 14 – 27 February 2015 Political Monitor 2015 POLITICAL MONITOR NO.7 OFFICIAL MEDIA GOVERNMENT ANNOUNCES MARTIAL LAW IN LAUKKAI, MONGLA REGION Fighting between Tatmadaw personnel and MNDAA (Kokang) forces continued in Laukkai and Kokang on 18 February. About 200 Kokang groups attacked a battalion near Parsinkyaw village with small and heavy weapons on 17 February evening and withdrew when the battalion responded. Similarly, from 17 February evening to 18 February morning, MNDAA troops attacked Tatmadaw camps with small and heavy weapons and withdrew when counter-attacks were launched. In addition, Tatmadaw personnel who were heading to troops in Laukkai on major communication route to Laukkai such as Hsenwi-Namslag-Kunglong road, Kutkai-Tamoenye-Monesi-Tapah road and Kutkai-Muse-Kyukok-Monekoe-Tangyan were also ambushed or attacked by Kokang groups, KIA, TNLA and SSA (Wanghai). From 15 to 18 February, SSA (Wanhai) forces attacked the Tatmadaw columns between Kyaukme and Hsipaw, Lashio and Hsenwi while KIA and TNLA ambushed the Tatmadaw 3 times between Hsenwi and Kyukok, 2 times between Kutakai and Monsi and once between Monesi and Tapah. Kokang troops also ambushed the Tatmadaw column 4 times between Parsinkyaw and Chinshwehaw. Due to the clashes, the government announced a state of emergency and martial law in the Kokang Self-Administered Zone on 17 February. In a separate statement, the Commander-in-Chief of Defence Services appointed the Regional Control Commander (Laukkai) Col Saw Myint Oo to exercise the executive powers and duties and judicial powers and duties concerning community peace and tranquillity and prevalence of law and order in Kokang Self-Administrative Zone. -

1. India and Myanmar: Understanding the Partnership – Sampa Kundu

MYANMAR AND SOUTH ASIA 1. India and Myanmar: Understanding the Partnership – Sampa Kundu, Institute for Defence Studies and Analysis, New Delhi, India; PhD Candidate, School of International Studies, Jawarhalal Nehru University, New Delhi, India Abstract: India’s bilateral relations with Myanmar has raised both optimism and doubts because of a number of ups and downs which portray India’s vague willingness to remain favoured by the Myanmar government and Myanmar’s calculated desire to get advantages from its giant neighbours including India. Scholars and practitioners have explained many times why both India and Myanmar need each other. Some may call it a realist politics and some may call it a fire-brigade alarm politics which implies that both of them act according to the need of the time. The objective of this paper is to explain the necessities of India and Myanmar to each other and how they respond to each other in different times. Connectivity, security, energy and economy are four major pillars of Indo- Myanmar bilateral relationship. Hence, each of these four sectors would have their due share in the proposed paper to illustrate the present dynamics of Indo-Myanmar partnerships. Factors like US, China and the regional cooperation initiatives including ASEAN and BIMSTEC are the external factors that are most likely to shape the future of the Indo-Myanmar relationships. Hence, a simultaneous effort would also be taken to explain the extent of their influence on the same. Based on available primary and secondary literature and field trips, this account will help the readers to contextualise Indo-Myanmar relationship in the light of international relations. -

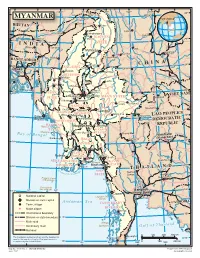

Map of Myanmar

94 96 98 J 100 102 ° ° Indian ° i ° ° 28 n ° Line s Xichang Chinese h a MYANMAR Line J MYANMAR i a n Tinsukia g BHUTAN Putao Lijiang aputra Jorhat Shingbwiyang M hm e ra k Dukou B KACHIN o Guwahati Makaw n 26 26 g ° ° INDIA STATE n Shillong Lumding i w d Dali in Myitkyina h Kunming C Baoshan BANGLADE Imphal Hopin Tengchong SH INA Bhamo C H 24° 24° SAGAING Dhaka Katha Lincang Mawlaik L Namhkam a n DIVISION c Y a uan Gejiu Kalemya n (R Falam g ed I ) Barisal r ( r Lashio M a S e w k a o a Hakha l n Shwebo w d g d e ) Chittagong y e n 22° 22° CHIN Monywa Maymyo Jinghong Sagaing Mandalay VIET NAM STATE SHAN STATE Pongsali Pakokku Myingyan Ta-kaw- Kengtung MANDALAY Muang Xai Chauk Meiktila MAGWAY Taunggyi DIVISION Möng-Pan PEOPLE'S Minbu Magway Houayxay LAO 20° 20° Sittwe (Akyab) Taungdwingyi DEMOCRATIC DIVISION y d EPUBLIC RAKHINE d R Ramree I. a Naypyitaw Loikaw w a KAYAH STATE r r Cheduba I. I Prome (Pye) STATE e Bay Chiang Mai M kong of Bengal Vientiane Sandoway (Viangchan) BAGO Lampang 18 18° ° DIVISION M a e Henzada N Bago a m YANGON P i f n n o aThaton Pathein g DIVISION f b l a u t Pa-an r G a A M Khon Kaen YEYARWARDY YangonBilugyin I. KAYIN ATE 16 16 DIVISION Mawlamyine ST ° ° Pyapon Amherst AND M THAIL o ut dy MON hs o wad Nakhon f the Irra STATE Sawan Nakhon Preparis Island Ratchasima (MYANMAR) Ye Coco Islands 92 (MYANMAR) 94 Bangkok 14° 14° ° ° Dawei (Krung Thep) National capital Launglon Bok Islands Division or state capital Andaman Sea CAMBODIA Town, village TANINTHARYI Major airport DIVISION Mergui International boundary 12° Division or state boundary 12° Main road Mergui n d Secondary road Archipelago G u l f o f T h a i l a Railroad 0 100 200 300 km Chumphon The boundaries and names shown and the designations Kawthuang 10 used on this map do not imply official endorsement or ° acceptance by the United Nations. -

Analysis of Drivers of Deforestation and Forest Degradation in Shan State and Strategic Options to Address Them

Final Report Analysis of Drivers of Deforestation and Forest Degradation in Shan State and Strategic Options to Address them FOREST MONREC M i n n is o t ti ry va of ser Natu l Con ral Re enta sourc ironm es nv & E 2 Final Report Analysis of Drivers of Deforestation and Forest Degradation in Shan State and Strategic Options to Address them Authors Aung Aung Myint, National Consultant on analysis of drivers of deforestation and forest degradation in Shan State, ICIMOD-GIZ REDD+ project [email protected]: +95 9420705116. December 2018 i Copyright © 2018 International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD) This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial, No Derivatives 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/). Published by International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD) GP Box 3226, Kathmandu, Nepal Production team Bill Wolfe (Consultant editor) Rachana Chettri (Editor) Dharma R Maharjan (Graphic designer) Asha Kaji Thaku (Editorial assistance) Cover photo: On the way from MongPyin to KyaingTong, eastern Shan State. Most of the photos used in the report were taken by the consultant on the eld survey of the Illicit Crop Monitoring in Myanmar-Opium Survey (ICMP) project (TD/MYA/G43 & TD/MYA/G44) under UNODC in 2014 and 2015. Reproduction This publication may be produced in whole or in part and in any form for educational or non-prot purposes without special permission from the copyright holder, provided acknowledgement of the source is made. ICIMOD would appreciate receiving a copy of any publication that uses this publication as a source.