Puerto Rico, Colonialism In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

District of Columbia Statehood and Voting Representation

Updated June 29, 2020 District of Columbia Statehood and Voting Representation On June 26, 2020, the U.S. House of Representatives have included full statehood or more limited methods of considered and passed the Washington, D.C. Admission providing DC residents the ability to vote in congressional Act, H.R. 51. This marked the first time in 27 years a elections. Some Members of Congress have opposed these District of Columbia (DC) statehood bill was considered on legislative efforts and recommended maintaining the status the floor of the House of Representatives, and the first time quo. Past legislative proposals have generally aligned with in the history of Congress a DC statehood bill was passed one of the following five options: by either the House or the Senate. 1. a constitutional amendment to give DC residents voting representation in This In Focus discusses the political status of DC, identifies Congress; concerns regarding DC representation, describes selected issues in the statehood process, and outlines some recent 2. retrocession of the District of Columbia DC statehood or voting representation bills. It does not to Maryland; provide legal or constitutional analysis on DC statehood or 3. semi-retrocession (i.e., allowing qualified voting representation. It does not address territorial DC residents to vote in Maryland in statehood issues. For information and analysis on these and federal elections for the Maryland other issues, please refer to the CRS products listed in the congressional delegation to the House and final section. Senate); 4. statehood for the District of Columbia; District of Columbia and When ratified in 1788, the U.S. -

Environmental Assessment for the Replacement of the Pier and Boat Ramp at the U.S

Draft Environmental Assessment for the Repairs and Replacement of the Boat Ramp and Pier at the US Border Patrol Air and Marine Facility, Ponce, Puerto Rico Environmental Assessment for the Replacement of the Pier and Boat Ramp at the U.S. Border Patrol & Air and Marine Facility, Ponce, Puerto Rico U.S. Customs and Border Protection February 2019 Draft Environmental Assessment for the Repairs and Replacement of the Boat Ramp and Pier at the US Border Patrol Air and Marine Facility, Ponce, Puerto Rico Environmental Assessment for the Replacement of the Pier and Boat Ramp at the U.S. Border Patrol & Air and Marine Facility, Ponce, Puerto Rico Environmental Assessment for the Replacement of the Pier and Boat Ramp at the U.S. Border Patrol & Air and Marine Facility, Ponce, Puerto Rico Lead Agency: U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) Proposed Action: The demolition and removal of the temporary structure, removal of the original pier, construction of a new pier, and replacement of the boat ramp at 41 Bonaire Street in the municipality of Ponce, Puerto Rico. The replacement boat ramp would be constructed in the same location as the existing boat ramp, and the pier would be constructed south of the Ponce Marine Unit facility. For Further Information: Joseph Zidron Real Estate and Environmental Branch Chief Border Patrol & Air and Marine Program Management Office 24000 Avila Road, Suite 5020 Laguna Niguel, CA 92677 [email protected] Date: February 2019 Abstract: CBP proposes to remove the original concrete pier, demolish and remove the temporary structure, construct a new pier, replace the existing boat ramp, and continue operation and maintenance at its Ponce Marine Unit facility at 41 Bonaire Street, Ponce, Puerto Rico. -

Ruling America's Colonies: the Insular Cases Juan R

YALE LAW & POLICY REVIEW Ruling America's Colonies: The Insular Cases Juan R. Torruella* INTRODUCTION .................................................................. 58 I. THE HISTORICAL BACKDROP TO THE INSULAR CASES..................................-59 11. THE INSULAR CASES ARE DECIDED ......................................... 65 III. LIFE AFTER THE INSULAR CASES.......................... .................. 74 A. Colonialism 1o ......................................................... 74 B. The Grinding Stone Keeps Grinding........... ....... ......................... 74 C. The Jones Act of 1917, U.S. Citizenship, and President Taft ................. 75 D. The Jones Act of 1917, U.S. Citizenship, and ChiefJustice Taft ............ 77 E. Local Self-Government v. Colonial Status...........................79 IV. WHY THE UNITED STATES-PUERTO Rico RELATIONSHIP IS COLONIAL...... 81 A. The PoliticalManifestations of Puerto Rico's Colonial Relationship.......82 B. The Economic Manifestationsof Puerto Rico's ColonialRelationship.....82 C. The Cultural Manifestationsof Puerto Rico's Colonial Relationship.......89 V. THE COLONIAL STATUS OF PUERTO Rico Is UNAUTHORIZED BY THE CONSTITUTION AND CONTRAVENES THE LAW OF THE LAND AS MANIFESTED IN BINDING TREATIES ENTERED INTO BY THE UNITED STATES ............................................................. 92 CONCLUSION .................................................................... 94 * Judge, United States Court of Appeals for the First Circuit. The substance of this Article was presented in -

Testimony Medicaid and CHIP in the U.S. Territories

Statement of Anne L. Schwartz, PhD Executive Director Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission Before the Health Subcommittee Committee on Energy and Commerce U.S. House of Representatives March 17, 2021 i Summary Medicaid and CHIP play a vital role in providing access to health services for low-income individuals in the five U.S. territories: American Samoa, the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands, Guam, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands. The territories face similar issues to those in the states: populations with significant health care needs, an insufficient number of providers, and constraints on local resources. With some exceptions, they operate under similar federal rules and are subject to oversight by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. However, the financing structure for Medicaid in the territories differs from state programs in two key respects. First, territorial Medicaid programs are constrained by an annual ceiling on federal financial participation, referred to as the Section 1108 cap or allotment (§1108(g) of the Social Security Act). Territories receive a set amount of federal funding each year regardless of changes in enrollment and use of services. In comparison, states receive federal matching funds for each state dollar spent with no cap. Second, the federal medical assistance percentage (FMAP) is statutorily set at 55 percent rather than being based on per capita income. If it were set using the state formula, the matching rate for all five territories would be significantly higher, and for most, would likely be the maximum of 83 percent. These two policies have resulted in chronic underfunding of Medicaid in the territories, requiring Congress to step in at multiple points to provide additional resources. -

Excavations at Maruca, a Preceramic Site in Southern Puerto Rico

EXCAVATIONS AT MARUCA, A PRECERAMIC SITE IN SOUTHERN PUERTO RICO Miguel Rodríguez ABSTRACT A recent set of radiocarbon dated shows that the Maruca site, a preceramic site located in the southern coastal plains of Puerto Rico, was inhabited between 5,000 and 3,000 B.P. bearing the earliest dates for human habitation in Puerto Rico. Also the discovery in the site of possible postmolds, lithic and shell workshop areas and at least eleven human burials strongly indicate the possibility of a permanent habitation site. RESUME Recientes fechados indican una antigüedad entre 5,000 a 3000 años antes de del presente para Maruca, una comunidad Arcaica en la costa sur de Puerto Rico. Estos son al momento los fechados más antiguos para la vida humana en Puerto Rico. El descubrimiento de socos, de posible talleres líticos, de áreas procesamiento de moluscos y por lo menos once (11) enterramientos humanos sugieren la posibilidad de que Maruca sea un lugar habitation con cierta permanence. KEY WORDS: Human Remains, Marjuca Site, Preceramic Workshop. INTRODUCTION During the 1980s archaeological research in Puerto Rico focused on long term multidisciplinary projects in early ceramic sites such as Sorcé/La Hueca, Maisabel and Punta Candelera. This research significantly expanded our knowledge of the life ways and adaptive strategies of Cedrosan and Huecan Saladoid cultures. Although the interest in these early ceramic cultures has not declined, it seems that during the 1990s, archaeological research began to develop other areas of interest. With the discovery of new preceramic sites of the Archaic age found during construction projects, the attention of specialists has again been focused on the first in habitants of Puerto Rico. -

Cyperaceae of Puerto Rico. Arturo Gonzalez-Mas Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1964 Cyperaceae of Puerto Rico. Arturo Gonzalez-mas Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Gonzalez-mas, Arturo, "Cyperaceae of Puerto Rico." (1964). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 912. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/912 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This dissertation has been 64—8802 microfilmed exactly as received GONZALEZ—MAS, Arturo, 1923- CYPERACEAE OF PUERTO RICO. Louisiana State University, Ph.D., 1964 B o ta n y University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan CYPERACEAE OF PUERTO RICO A Dissertation I' Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Botany and Plant Pathology by Arturo Gonzalez-Mas B.S., University of Puerto Rico, 1945 M.S., North Carolina State College, 1952 January, 1964 PLEASE NOTE: Not original copy. Small and unreadable print on some maps. Filmed as received. UNIVERSITY MICROFILMS, INC. ACKNOWLEDGMENT The author wishes to express his sincere gratitude to Dr. Clair A. Brown for his interest, guidance, and encouragement during the course of this investigation and for his helpful criticism in the preparation of the manuscript and illustrations. -

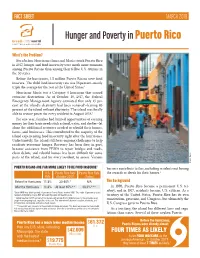

Hunger and Poverty in Puerto Rico

FACT SHEET MARCH 2019 Hunger and Poverty in Puerto Rico What’s the Problem? Even before Hurricanes Irma and Maria struck Puerto Rico in 2017, hunger and food insecurity were much more common among Puerto Ricans than among their fellow U.S. citizens in the 50 states. Before the hurricanes, 1.5 million Puerto Ricans were food insecure. The child food insecurity rate was 56 percent—nearly triple the average for the rest of the United States.1 Hurricane Maria was a Category 4 hurricane that caused extensive destruction. As of October 10, 2017, the Federal Emergency Management Agency estimated that only 15 per- cent of the island’s electricity had been restored2—leaving 85 percent of the island without electricity. The island was finally able to restore power for every resident in August 2018.3 For one year, families had limited opportunities of earning money for their basic needs such as food, water, and shelter—let alone the additional resources needed to rebuild their homes, farms, and businesses. This contributed to the majority of the island experiencing food insecurity right after the hurricanes. Unfortunately, the island still faces ongoing challenges to help residents overcome hunger. Recovery has been slow, in part, because assistance from FEMA to repair bridges and roads, clean debris, and rebuild homes has been difficult for some parts of the island, and for every resident, to access. Various iStock photo 5 PUERTO RICANS ARE FAR MORE LIKELY TO BE FOOD INSECURE barriers contribute to this, including residents not having U.S. Puerto Rico Rate Puerto Rico Rate the records or deeds for their homes.4 Rate (October 2017) (Today) Before the Hurricanes 11.8% 30-60%* N/A The Background After the Hurricanes 11.8% At least 85%** 38.3%*** In 1898, Puerto Rico became a permanent U.S. -

Luis Muñoz Rivera 1859–1916

H former members 1898–1945 H Luis Muñoz Rivera 1859–1916 RESIDENT COMMISSIONER 1911–1916 UNIONIST FROM PUERTO RICO he leading voice for Puerto Rican autonomy in a proponent of home rule. Muñoz Rivera attended the the late 19th century and the early 20th century, local common (public) school between ages 6 and 10, Luis Muñoz Rivera struggled against the waning and then his parents hired a private tutor to instruct him. TSpanish empire and incipient U.S. colonialism to carve According to several accounts, Muñoz Rivera was largely out a measure of autonomy for his island nation. Though self-taught and read the classics in Spanish and French. As a devoted and eloquent nationalist, Muñoz Rivera had a young man, he wrote poetry about his nationalist ideals, acquired a sense of political pragmatism, and his realistic eventually becoming a leading literary figure on the island appraisal of Puerto Rico’s slim chances for complete and publishing two collections of verse: Retamas (1891) sovereignty in his lifetime led him to focus on securing and Tropicales (1902). To make a living, Muñoz Rivera a system of home rule within the framework of the initially turned to cigar manufacturing and opened a American empire. To that end, he sought as the island’s general mercantile store with a boyhood friend. His father Resident Commissioner to shape the provisions of the had taught him accounting, and he became, according to Second Jones Act, which established a system of territorial one biographer, a “moderately successful businessman.”3 rule in Puerto Rico for much of the first half of the 20th Muñoz Rivera married Amalia Marín Castillo in 1893.4 century. -

Political Status of Puerto Rico: Brief Background and Recent Developments for Congress

Political Status of Puerto Rico: Brief Background and Recent Developments for Congress R. Sam Garrett Specialist in American National Government June 12, 2017 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov R44721 Political Status of Puerto Rico: Brief Background and Recent Developments for Congress Summary Puerto Rico lies approximately 1,000 miles southeast of Miami and 1,500 miles from Washington, DC. Despite being far outside the continental United States, the island has played a significant role in American politics and policy since the United States acquired Puerto Rico from Spain in 1898. Puerto Rico’s political status—referring to the relationship between the federal government and a territorial one—is an undercurrent in virtually every policy matter on the island. In a June 11, 2017, plebiscite (popular vote), 97.2% of voters chose statehood when presented with three options on the ballot. Turnout for the plebiscite was 23.0% of eligible voters. Some parties and other groups opposing the plebiscite had urged their bases to boycott the vote. (These data are based on 99.5% of precincts reporting results.) After initially including only statehood and free association/independence options, an amended territorial law ultimately permitted three options on the plebiscite ballot: statehood, free association/independence, or current territorial status. Before the latest plebiscite, Puerto Ricans most recently reconsidered their status through a 2012 plebiscite. On that occasion, voters were asked two questions: whether to maintain the status quo, and if a change were selected, whether to pursue statehood, independence, or status as a “sovereign free associated state.” Majorities chose a change in the status quo in answering the first question, and statehood in answering the second. -

Iaino, Spanish, and African Roots C

- OF THE PUERTO RICAN PEOPLE: A CARTOGRAPHY (PART I) • I ; e._~e ..r\y 1800s 116.,..._.. 1493 November 19, , DOMINICAN I REPUBLIC N"" .. · ~ Iaino, Spanish, and African Roots c. 2000 BC-1898 c. 2000 BC EARLY 1500s -1873 1765- EARLY 1800s Arawak/Tafno migrations from North and South America to the Hispanicized black (ladinos) of Moorish descent were expelled The Spanish Crown introduces reforms aimed at increasing The Real Cedula de Gracias [Royal Decree of Graces] of 1815, Caribbean islands. The Tafno period begins in Puerto Rico from Spain and brought to Puerto Rico by the Spaniards in the Puerto Rico's population and promoting economic develop opens up trade with other countries besides Spain. New immi around the year 1200 AD, almost three centuries before Chris early 1500s. Large numbers of enslaved black Africans were ment. It encourages immigration primarily from various regions grants come to the island from over a dozen other countries France, Corsica, Italy, Germany, Great Britain, Ireland, Scotland, topher Columbus' arrival to the island (1493) and the begin of Spain and there is also an increase in the black enslaved introduced to the island after 1519, mostly from several West Holland, and the United States among them. They were labor to support the expansion of agricultural production. ning of Spanish colonization ( 1508). African tribal regions. With the rapid decline of the Tafno indi required to be Catholic and pledge their loyalty to Spain. genous population due to the violence of conquest, forced Strong commercial relations developed between Puerto Rico NOVEMBER 19 1493 labor, and illnesses, by 1530 over half of the island's total 1791-1804 and the United States in subsequent decades. -

Guide to Theecological Systemsof Puerto Rico

United States Department of Agriculture Guide to the Forest Service Ecological Systems International Institute of Tropical Forestry of Puerto Rico General Technical Report IITF-GTR-35 June 2009 Gary L. Miller and Ariel E. Lugo The Forest Service of the U.S. Department of Agriculture is dedicated to the principle of multiple use management of the Nation’s forest resources for sustained yields of wood, water, forage, wildlife, and recreation. Through forestry research, cooperation with the States and private forest owners, and management of the National Forests and national grasslands, it strives—as directed by Congress—to provide increasingly greater service to a growing Nation. The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, disability, and where applicable sex, marital status, familial status, parental status, religion, sexual orientation genetic information, political beliefs, reprisal, or because all or part of an individual’s income is derived from any public assistance program. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TDD).To file a complaint of discrimination, write USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, 1400 Independence Avenue, S.W. Washington, DC 20250-9410 or call (800) 795-3272 (voice) or (202) 720-6382 (TDD). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. Authors Gary L. Miller is a professor, University of North Carolina, Environmental Studies, One University Heights, Asheville, NC 28804-3299. -

Culebra National Wildlife Refuge

Culebra National Wildlife Refuge Comprehensive Conservation Plan U.S. Department of the Interior Fish and Wildlife Service Southeast Region September 2012 COMPREHENSIVE CONSERVATION PLAN CULEBRA NATIONAL WILDLIFE REFUGE Culebra, Puerto Rico U.S. Department of the Interior Fish and Wildlife Service Southeast Region Atlanta, Georgia September 2012 Culebra National Wildlife Refuge TABLE OF CONTENTS COMPREHENSIVE CONSERVATION PLAN I. BACKGROUND ................................................................................................................................. 1 Introduction ...................................................................................................................................1 Purpose and Need for the Plan ....................................................................................................1 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service ......................................................................................................2 National Wildlife Refuge System ..................................................................................................2 Legal and Policy Context ..............................................................................................................4 Legal Mandates, Administrative and Policy Guidelines, and Other Special Considerations .......................................................................................................4 National and International Conservation Plans and Initiatives .....................................................5