The Schneiderman Case: an Inside View of the Roosevelt Court

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

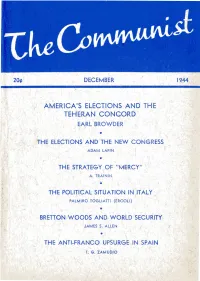

The Communist a Marxist Magazine Devoted to Advancement of Democratic Thought and Action

DECEMBER 1944 ,' AMERICA•s ELECTIONS AND THE TEHERAN CONCORD EA RL BROWDER ' I • THE ELECTipNS AND THE NEW CONGRESS ADAM LAPIN t ' r • THE STRATEGY OF "MERCY " A. TRAININ • THE POLITICA L SITUATION IN ITALY ( . PALMIRO TOGLIATTI (ERCOLI) • BRETTON WOODS AND WORLD SECURITY JAMES S. ALLEN • THE A NTI-FRA NCO U PS URG~ IN SPAIN T. G. ZAMUDIO Just Published- MORALE EDUCATION IN THE AMERICAN ARMY BY PHILIP FONER In this new study, a distinguished American historian brings to light a wealth of material, including documents and speeches by Washington, Jackson and Lincoln, letters from soldiers, contemporary newspaper articles and editorials, .)'esolutions and activities of workers' and other patriotic organi,2ations backing up the fighting fronts, all skiijfully woven together to make an illuminating analysis of the role of morale in the three great wars of American history-the War of Independence, the War of 1812, and the Civil War. Price 20¢ MARX AND ENGELS ON REACTION ARY PRUSSIANIS·M ~ An important theoretical study which assembles the writings and opinions of Marx and Engels on the histori~ roots, .charaCter and reafclonary political and military role of the Prussian Junkers, and illuminates the background of the plans for world domination hatched by the Ge;man general staH, the modern industrialists_and the criminal Nazi clique. Prle..e iO¢ WALT WHIT MAN- POET OF AMERICAN DEMOCRACY BY SAMUEL SILLEN A new study of the great American poet, together with a discerning selec- - tion from his prose and poetic writings which throws light on Whitman's views on the Civil War, democracy, labor, internationalism, culture, etc. -

Red Paradise: a Long Life in the San Diego Communist Movement

Red Paradise: A Long Life in the San Diego Communist Movement By Toby Terrar In December 2013, San Diego resident Milton Lessner, who has been a dues- paying member of the Communist Party, USA, since 1931, celebrated his 100th birthday. Like most of his comrades, he never held a leadership position in or publicly identified himself as a party member. He sees no purpose in using his last name now, but is otherwise happy with sharing an account of his life in the party’s San Diego branch. For much of the twentieth century San Diego had a small community consisting of Communist Party members and their non- party friends. Milt comments that they lacked both the glamorous Hollywood connections enjoyed in Los Angeles and the large numbers of party members in New York and Chicago. They were practically invisible when compared to San Diego’s local military-industrial complex.1 But in an earlier period their work on behalf of the city’s trade unions, civil rights, peace movement, consumer empowerment, and housing contributed positively to the city’s history and should not be totally forgotten. Milt was born on December 11, 1913, in New Haven, Connecticut, where his 24-year-old father Henry worked in a watch factory.2 Henry and his wife Bessie were of Jewish heritage.3 His father, although not political, was a member of Workmen’s Circle, which was a Yiddish language, American Jewish fraternal organization.4 Soon after Milt’s birth, they settled at Scienceville near Youngstown, Ohio, and started a mom-and-pop grocery store.5 Milt had an older brother Herbert, born in 1912, and a younger brother Eugene, born in 1920.6 Toby Terrar, a native San Diegan, attended UCLA where he studied Catholic church history with Gary Nash. -

The Communist

' r - Have you read your copy of E~rl ~rowd er 's · t~test b ~o k , . I . n;E WAY OUT, yet? , l This book is .a magnificent 1guide , to the present events ·· which are r ~ha ping: the· world. It co'ntdins the articles ~ " . and utterances whiCh ~B r owder ·placed before the Amari.- '- can people durin g tne p a st~ ye ar. It i~ THE book of 'the 'a nti- w<~r movement in the Uhited States: ' I ' • I . j t --. J There is no better· wa y to ~d u eate the pe.,ople of Amer i c~ 0. l I ~ - fo ii; realization of tne path, they must t a:k~ to keep war fr om America than to get this ke en ana eloquent book b tr,cl·' , I -t ~ ') the Ge,erai, Secretary of tile Com~tmist Party into the hanas pf i~e puDiic. - - Browder IS ., Atlanta prison. But I his message to his fellow-Americans ~burns b rig~t.er ·t han, ever ip the pages· of THE WAY O~T. , Ans er the persecution of Ea r1 ·. Br.owder py buyin~ .his book 4nd sprel!dtpg iHa.r and wide ' ' through the factories, offices,' and home~ of the country. / ~ '( , } j • 256. pages. Price $I .00 • .Or der from LIBRARY PUB LISHERS P. 0. Box 148, Station D, New York, N". Y. VOL. XX, No. 6 JUNE, 1941 THE COMMUNIST A MAGAZINE OF THE THEORY AND PRACTICE OF MARXISM-LENINISM PUBLISHED MONTHLY BY THE COMMUNIST PARTY OF THE U.S.A. -

U588o55 1948.Pdf

100 Things You Should Know About Communism in the U. S. A. Forty years ago, Communism was just a plot in the minds of a very few peculiar people. Today, Communism is a world force governing millions of the human race and threatening to govern all of it. Who are the Communists? How do they work? What do they want? What would they do to you? For the past IO years your committee has studied these and other questions and now some positive answers can be made. Some answers will shock the citizen who has not examined Com- munism closely. Most answers will infuriate the Communists. These answers are given in five booklets, as follows: 1. One Hundred Things You Should Know About Commu- nism in the U. S. A. 2. One Hundred Things You Should Know About .Commu- nism in Religion. 3. One Hundred Things You Should Know About Commu- nism in Education. 4. One Hundred Things You Should Know About Commu- nism in Labor. 5. One Hundred Things You Should Know About Commu- nism in Government. These booklets are intended to help you know a Communist when you hear him speak and when you see him work. If you ever find yourself in open debate with a Communist the facts here given can be used to destroy his arguments completely and expose him as he is for all to see. Every citizen owes himself and his family the truth about Com- munism because the world today is faced with a single choice: To go Communist or not to go Communist. -

CALIFORNIA RED a Life in the American Communist Party

alifornia e California Red CALIFORNIA RED A Life in the American Communist Party Dorothy Ray Healey and Maurice Isserman UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS PRESS Urbana and Chicago Illini Books edition, 1993 © 1990 by Oxford University Press, Inc., under the title Dorothy Healey Remembers: A Life in the American Communist Party Reprinted by arrangement with Oxford University Press, Inc., New York, New York Manufactured in the United States of America P54321 This book is printed on acidjree paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Healey, Dorothy. California Red : a life in the American Communist Party I Dorothy Ray Healey, Maurice Isserman. p. em. Originally published: Dorothy Healey remembers: a life in the American Communist Party: New York: Oxford University Press, 1990. Includes index. ISBN 0-252-06278-7 (pbk.) 1. Healey, Dorothy. 2. Communists-United States-Biography. I. Isserman, Maurice. II. Title. HX84.H43A3 1993 324.273'75'092-dc20 [B] 92-38430 CIP For Dorothy's mother, Barbara Nestor and for her son, Richard Healey And for Maurice's uncle, Abraham Isserman ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This work is based substantially on a series of interviews conducted by the UCLA Oral History Program from 1972 to 1974. These interviews appear in a three-volume work titled Tradition's Chains Have Bound Us(© 1982 The Regents of The University of California. All Rights Reserved. Used with Permission). Less formally, let me say that I am grateful to Joel Gardner, whom I never met but whose skillful interviewing of Dorothy for Tradition's Chains Have Bound Us inspired this work and saved me endless hours of duplicated effort a decade later, and to Dale E. -

Volume 22 No. 12, December, 1943

20¢ DECEMBER 1943 THE MOSCOW CONFERENCE EARL BROWDER EUGENE DENNIS • THE NOVEMBER ELECTIONS GILBERT GREEN ARNOLD JOHNSON SAMUEL ADAMS DARCY WILLIAM SCHNEIDERMAN WILLIAM NORMAN • LABOR'S NATIONAL CONVENTIONS WILLIAM Z. FOSTER J. K. MORTON FORTHCOMING PUBLICATIONS Soviet Economy and the War By Maurice Dobb A factual record of economic developments during the last few years with special reference to their bearing on the war potential and the needs _of the war. Price $.25 Soviet Planning and Labor _in Peace and War By Maurice Dobb A study of economic planning, the financial system, woFk, wages, the economic effects of the war, and other special aspects of :fhe Soviet economic system prior to and during the war. Price $.35 The Red Army By Prof. I. Minx The history and organization of the Red Army and a record of its achievements from its foundation up to the epic victory at Stalingrad. Price $1.25 V. I. Lenin: A Biography Prepared by the Marx-Engels-Lenil') Institute, this .volume pro vides a new and authoritative study of the life and activities of the fou nder and leader of the Soviet Union up to the time of Lenin's death. Price $1 .90 Wendell Phillips By James J. Green An evaluation of the life and work of the great Abolitionist leader who distinguished himself in the fight for Negro emancipation, free education, women's rights, universal suffrage and other pro gressive causes. · Price $.15 • WORKERS LIBRARY PUBLISHERS P.O. lox 148, Station D (832 Broadway), New York 3, N.Y. VOL. XXII, No. 12 DECEMBER, 1943 THE COMMUNIST A MAGAZINE OF THE THEORY AND PRACTICE OF MARXISM-LENINISM EDITOR: EARL BROWDER CONTENTS The Three-Power Conference at Moscow Earl Browder 1059 The Three-Power Conference Documents 1065 Speed the Day of Victory Joseph Stalin . -

Nat Ganley Papers

THE NAT GANLEY COLLECTION 3* Manuscript boxes 2 Paige boxes 1 scrapbook Processed: June 1971 Accession Number 320 The papers of Nat Ganley were deposited with the Archives of Labor History and Urban Affairs in June, 1970 by Mrs. Ann Ganley. Nat Ganley was born Nathan Kaplan in New York City on November 26, 1903. His formal education ended with his completion of the eighth grade in the NYC public schools. Ganley became a Socialist just prior to the Russion Revolution and soon after he joined the Junior Section of the Young Peoples Socialist League in New York. In 1919 Ganley turned his attention to helping develop the Communist movement in the United States. During the 1920's he worked in many capacities within the Communist movement. Much of his activities centered around the Communist youth movement. While following these interests, Ganley served as first director of communist children's work in the United States and as National Secretary of the Communist youth movement. In' the early 1930' s Ganley was on the staff of the Daily Worker and. served as the <:New England District Organizer for the Communist Party. It was during this period that Ganley began to take an active role in union organizing. Specifically, in 1931-1932 he helped organize the National Textile Workers Union in Lawrence, Mass. and Providence, R.I. In 1934 he came to Detroit and used the name Ganley for the first time to avoid being blacklisted by local employers. During the years 1934-1935 he was active in the Trade Union Unity League and helped organize many AFL locals including: the Poultry Workers Union, the Packing House Workers and the Riggers Union. -

THE PROBLEM OP AMERICAN COMMUNISM in 1945 And

THE PROBLEM OP AMERICAN COMMUNISM IN 1945 and Recommendations Rev, John P. Cronin, S# S, A Confidential Study for Private Circulation LAILIMI Uh KUbblAN LUNIKULANU INhLULNCE USSR IN 1939 [I) "TRUSTEESHIPS'ASKED BY RUSSIA RUSSIAN ANNEXATIONS. T939-45 OUTPOST FOR BALTIC CONTROL RUSSIAN OCCUPIED AREAS AND (3) RUSSIA CLAIMS TURKISH TERRITORY COMMUNIST PARTY STATES ® UTILIZATION OF COLONIAL UNREST STRONG RUSSIAN INFILTRATION (D SHARE ASKED IN OCCUPATION OF JAPAN CHINESE COMMUNIST AREAS J—i _Q_ TliE NETWORK Information Bulletin on European Stalinism 124 W. 85 St., New York 24, N.Y. (Tel. TR 7-0793) October 15, 1945 ii INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY This is a confidential survey of the problem of American Communism. At the outset it is important to note the restrictions which must neces- sarily govern the use of this Report. The writer faced the choice between a more general study which might be used extensively, and a detailed analy- sis which names names. The latter alternative was chosen as being the more j valuable to the sponsors of the survey. Accordingly, instead of confin- ing the reporting to material which is generally available to the public, the author used accurate but confidential sources. The usefulness of these * sources would cease if their names and positions were revealed. This is particularly true i»^en__the ultimate source is a well-placed member of the Communist Party. " " " !—• ----- ' • ,1 Because of the accuracy of the sources, it is often possible to 1/ name definitely as Communists individuals who would publicly deny their jj affiliation. The publication of such names would certainly lead to a challenge to produce proof and possibly to a libel suit. -

Japanese and Chinese Immigrant Activists

Japanese and Chinese Immigrant Activists Japanese and Chinese Immigrant Activists Organizing in American and International Communist Movements, 1919–1933 JOSEPHINE FOWLER RUTGERS UNIVERSITY PRESS NEW BRUNSWICK, NEW JERSEY, AND LONDON LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA Fowler, Josephine Japanese and Chinese immigrant activists : organizing in American and international Communist movements, 1919–1933 / Josephine Fowler. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-8135-00-5 (alk. paper) ISBN-13: 978-0-8135-01-2 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Communist Party of the United States of America--History. 2. Japanese Americans--Politics and government. 3. Chinese Americans--Politics and government. Immigrants--United States--Political activity. I. Title. JK2391.C5F68 2007 32.273'75089951—dc22 2006031253 CIP A British Cataloging-in-Publication record for this book is available from the British Library. Copyright © 2007 by Josephine Fowler All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the publisher. Please contact Rutgers University Press, 100 Joyce Kilmer Avenue, Piscataway, NJ 0885-8099. The only exception to this prohibition is “fair use” as defined by U.S. copyright law. Manufactured in the United States of America For my mother, Nevi Unti Fowler, and my late father, Joseph William Fowler CONTENTS Illustrations ix Acronyms xi Acknowledgments xiii Introduction -

DEPARTMENT of JUSTICE INVESTIGATIVE FILES V =J Part I

A Guide to the Microfilm Edition of Research Collections in American Radicalism General Editors: Mark Naison and Maurice Isserman ^= _ ^ DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE INVESTIGATIVE FILES V =J Part I. The Industrial Workers of the World UNTVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA A Guide to the Microfilm Edition of Research Collections in American Radicalism General Editors: Mark Naison and Maurice Isserman DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE INVESTIGATIVE FILES Parti. The Industrial Workers of the World Edited by Melvyn Dubofsky Associate Editor Gregory Murphy Guide compiled by Martin Schipper A microfilm project of UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA An Imprint of CIS 4520 East-West Highway • Bethesda, MD 20814-3389 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Department of Justice investigative files [microfilm]. p. cm. -- (Research collections in American radicalism) Accompanied by printed reel guides, compiled by Martin P. Schipper. Includes indexes. Contents: pt. 1. The Industrial Workers of the World / edited by Melvyn Dubofsky • pt 2. The Communist Party / edited by Mark Naison. ISBN 1-55655-055-3 (microfilm : pt. 1) ISBN 1-55655-056-1 (microfilm : pt. 2) 1. Industrial Workers of the World-History-Sources. 2. Communist Party of America-History-Sources. 3. United States. Dept. of Justice-Archives. I. Schipper, Martin Paul. II. Dubofsky, Melvyn, 1934- . m. Naison, Mark, 1946- . IV. United States. Dept of Justice. V. University Publications of America (Firm) VI. Series. [HD8055] 322,.2~dc20 90-12989 CIP Copyright © 1989 by University Publications of America. All rights reserved. ISBN 1-55655-055-3. TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction v Source Note - ix Editorial Note ix Scope and Content Note xi Reel Index Reell RG 60•Straight Numerical File Casefde 150139 1 Casefile 185354 1 Casefde 150139 cont 2 Casefde 185354 cont 2 Reel 2 RG 60•Straight Numerical File cont. -

Property Rights and the Supreme Court in World War II James W

Journal of Supreme Court History ~. OFFICERS William J. Brennan, Jr., Honorary Trustee Lewis F. Powell, Jr., HonoralY Trustee Byron R. White, Honorary Trustee Justin A. Stanley, Chairman Leon Silverman, President PUBLICATIONS COMMITTEE Kenneth S. Geller, Chairman DonaldB.Ayer JamesJ. Kilpatrick Louis R. Cohen Michael H. Cardozo Melvin I. Urofsky BOARDOFEDlTORS Melvin I. Urofsky, Chairman Herman Belz Craig Joyce Maeva Marcus David J. Bodenhamer David O'Brien KermitHall Laura Kalman Michael Parrish MANAGING EDITOR Clare Cushman CONSULTlNG EDITORS Patricia R. Evans Kathleen Shurtleff James J. Kilpatric~ Jennifer M. Lowe David T. Pride Supreme Court Historical Society Board of Trustees Honorary Trustees William J. Brennan, Jr. Lewis F. Powell, Jr. Byron R. White Chainnan President Justin A. Stanley Leon Silverman Vice Presidents S. Howard Goldman Dwight D. Opperman Frank C. Jones E. Barrett Prettyman, Jr. Secretary Treasurer Virginia Warren Daly Sheldon S. Cohen Trustees George R. Adams Frank B. Gilben William Bradford Reynolds Noel J. Augustyn John D. Gordan, III John R. Risher, Jr. Herman Belz William T. Gossett Harvey Rishikof Barbara A. Black Fulton Haight William P. Rogers Hugo L. Black, Jr. GeoffreyC. Hazard. Jr. Bernard G. Segal Vera Brown Judith Richards Hope Jerold S. Solovy Wade Burger William E. Jackson Kenneth Starr Vincent C. Burke, Jr. Robb M. Jones Cathleen Douglas Stone Patricia Dwinnell Butler JamesJ. Kilpatrick Agnes N. Williams Andrew M. Coats Peter A. Knowles Lively Wilson WilliamT. Coleman,1r. Howard T. Markey W. Foster Wollen F. Elwood Davis Mrs. Thurgood Marshall M. Truman Woodward, Jr. Charlton Dietz Thurgood Marshall, Jr. John T. Dolan VincentL. McKusick William Edlund Francis J. -

Communists and the First Amendment: the Shaping of Freedom of Advocacy in the Cold War Era*

Communists And The First Amendment: The Shaping Of Freedom Of Advocacy In The Cold War Era* MARC ROHR** "Public opinion being what it now is, few will protest the convic- tion of these Communist petitioners. There is hope, however, that in calmer times, when present pressures, passions and fears sub- side, this or some later Court will restore the First Amendment liberties to the high preferred place where they belong in a free society." Justice Hugo Black, dissenting in Dennis v. United States, June 4, 1951.1 "[W]hatever reasons there may primarily once have been for regarding the Soviet Union as a possible, if not probable military opponent, the time for that sort of thing has clearly passed." George F. Kennan, testifying before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, April 4, 1989.2 * Copyright Marc Rohr 1991. ** B.A., Columbia, 1968; J.D. Harvard, 1971. Professor of Law, Nova University, Center for the Study of Law. This article was funded, in part, by a Goodwin Research Grant from Nova University. The author wishes to thank his colleagues, Professors Johnny C. Burris, Michael Dale, and Steven Friedland for their encouragement, sugges- tions, and comments throughout the process of researching and writing this article. 1. 341 U.S. 494, 581 (1951) (Black, J., dissenting). 2. Washington Post, April 5, 1989, at A22. George F. Kennan (born in 1904) is a former foreign service office, State Department official, U.S. Ambassador to the Soviet Union, and U.S. ambassador to Yugoslavia. In 1956 he became professor of historical studies at the Institute for Advanced Study at Princeton University.