AJR 2015 Pushback Journalism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WOMEN's EDITION

HONI SOIT Issue 8 may 4th 2011 WOMEN’s EDITION WE aCkNOWlEdgE ThE TradiTiONal OWNErS Of ThiS laNd, ThE gadigal pEOplE Of ThE EOra NaTiON. CONTENTSiON W E STa N d hE r E TOday aS T h E EdiT b ENEfiC iariES O f a raC i ST aN d EDITORIAL S u N r ECONCilE d diS p OSSESSi ON. mEN’ How many feminists does it take to change a light bulb? O WE rECOgNiSE bOTh Our privilEgE aNd Our W ObligaTiON TO rEmEmbEr ThE miSTakES One to change the bulb, and three to write about how the bulb is exploiting the Of ThE paST, aCT ON ThE prOblEmS Of socket. TOday aNd build fOr a fuTurE frEE frOm diSCrimiNaTiON. Ladies and gentlemen, welcome to the women’s edition of Honi Soit. If I were to mention that I was a feminist to most of you there would be many groans, probably some laughter and reactions such as “Pfft... women’s issues? Do they even exist anymore?” or “here we go, another ranting lefty”. But the fact of the matter is that in this modern, 21st century world we live in equal pay still isn’t a thing, abortion continues to stay illegal and casual sexism haunts the campus everyday and these Launch Party for aren’t just issues for the radicals. Women’s Honi This special edition of the paper was written and edited completely by female identifying individuals on campus, giving them the opportunity to submit pieces that Hey there boys and girls, come present the issues that effect them. -

The ACMA Has Dismissed Two Complaints from the Australian

Investigations 3195 and 3224 File no. ACMA2014/273 and ACMA2014/446 Broadcaster Australian Broadcasting Corporation Station ABC1 Type of service ABC television Name of program Media Watch Dates of broadcast 17 February 2014 and 24 February 2014 Relevant code Standards 2.1, 2.2, 3.1 and 5.3, and Section III of the ABC Code of Practice 2011 (revised in 2014) Date finalised 24 September 2014 Decision The Australian Broadcasting Corporation: did not breach standard 2.1 did not breach standard 2.2 did not breach standard 3.1 did not breach standard 5.3 complied with Section III of the ABC Code of Practice 2011 (revised in 2014) ACMA Report into investigations 3195 and 3244 – Media Watch broadcast by ABC1 on 17 and 24 February 2014 The complaints On 31 March 2014, the ACMA commenced an investigation into an episode of the program, Media Watch, broadcast by the ABC on 17 February 2014 (the first broadcast). The ACMA commenced its investigation following receipt of a complaint that the ABC breached standards 2.1, 3.1 and 5.3 of the ABC Code of Practice 2011 (revised in 2014) (the Code) in respect of the statement in the first broadcast (the statement) that: Insiders tell Media Watch that The Australian is losing $40 million to $50 million a year. On 5 June 2014, the ACMA commenced an investigation into an episode of Media Watch broadcast by the ABC on 24 February 2014 (the second broadcast). The ACMA commenced its further investigation following receipt of a complaint that the second broadcast ‘present[ed] facts in a misleading way’ and ‘did not correct errors in an appropriate way’. -

From the Desk of John Roskam, Executive Director [email protected]

From the desk of John Roskam, Executive Director [email protected] 3 June 2020 Dear IPA Member I'm pleased to be writing to you my End Of Financial Year letter for this year for the Institute of Public Affairs. With this letter I have attached a donation form for our 2020 End Of Financial Year Appeal. As you know the IPA doesn't seek or receive government funding. The IPA relies for its funding entirely upon the voluntary financial contributions provided by its Members and supporters. We depend on people like you. Last year the revenue of the IPA was $6 million, 85% of which came from donations and 15% from membership fees. All donations made to our 2020 End Of Financial Year Appeal are devoted exclusively to supporting the research of the IPA and are tax deductible. For the IPA the last twelve months has been a time of achievement and growth. While for Australia the last twelve months falls into two parts – the time up until the outbreak of the coronavirus pandemic in March, and the time after it. The IPA over the last twelve months More than 6,000 Australians are Members of the IPA, the highest number in our more than 70 year history, while our revenue and cash reserves are likewise at record levels. To accommodate the increase in the number of staff of now nearly 50 employees, the IPA doubled the size of its headquarters in Melbourne during the year. Those 50 IPA employees include our IPA Generation Liberty Campus Coordinators working at sixteen universities around the country. -

KENNEDY AWARDS Excellence in Australian Journalism

KENNEDY AWARDS Excellence in Australian Journalism 10th Anniversary Sponsorship Prospectus DIMITY CLANCEY AND LAURA MANGHAM OF A CURRENT AFFAIR WIN THE 2020 MIKE WILLESEE AWARD FOR OUTSTANDING NIGHTLY CURRENT AFFAIRS THE HISTORY OF THE KENNEDY AWARDS NAMED after the trailblazing indigenous journalist Les Kennedy, the Kennedy Awards were initially conceived in 2011 to recognise excellence in New South Wales journalism. Almost immediately the Kennedys were shaped by the nature of the entrants - attracting journalists from the likes of Four Corners, 60 Minutes, The Australian, A Current Affair, 730 Report, SBS and the Financial Review to become a truly independent, national celebration of Australian journalism. The awards were created by journalists for journalists - open to all-comers with no agendas or historical obligation to affiliation. A decade later the Kennedys have become the Australian media's night of nights - celebrated for their inclusiveness, independence, respect for the past and the value of fostering the next generation of the nation's finest journalists. SANDRA SALLY (RIGHT) PRESENTS THE HARRY POTTER AWARD FOR OUTSTANDING TV NEWS REPORTING J U N E 2 0 2 0 . Les Kennedy THE INSPIRATION OF THE KENNEDY AWARDS Les Kennedy was never in the officers' mess of journalism - and nor did he want to be. He loved nothing better than excelling on the road as a leader of other "shoe leather" journalists. Proud of his indigenous heritage, Les' awareness of his past and the pride he took in it were the twin chambers of a big, generous heart. It was his fabled generosity that fuelled a selfless devotion to a long list of protégés. -

Australia's Future in the Balance

POLICY CONTENTS ideas • debate • opinion Volume 31 No. 2 • Winter 2015 SYMPOSIUM ON FEMINISM ARTICLES 3 The Corruption of Feminism 39 Free Trade & Its Exceptions When human rights stopped being about Do they apply to Australia today? freedom, so did feminism. Sinclair Davidson Janet Albrechtsen 45 How Ideas Spread 7 Global Women’s Issues One CIS report’s 20-year journey Why we still need feminism. around the globe. Andrea den Boer Wolfgang Kasper 12 New Feminism’s War on Women 49 Laudato Si’: Well Intentioned, The arguments once made by misogynists Economically Flawed are now made by feminists. Pope Francis has too negative a view Brendan O’Neill of markets, but he is no Marxist. Samuel Gregg FEATURES RESEARCH 15 Australia’s Future in the Balance 52 Charter Schools, Free Schools, Overcoming antagonism and reigniting and School Autonomy enterprise and prosperity. The prospects for innovative education Wolfgang Kasper & Paul Kelly models in Australia. 24 Magna Carta: The Rule of Law Jennifer Buckingham & Trisha Jha and Liberty The principles inherent in the document developed by incremental steps. BOOK REVIEWS James Spigelman 59 Christian Reconstruction: 32 Magna Carta: 800 Years of Law R. J. Rushdoony and American Religious Conservatism & Liberty By Michael Joseph McVicar From Scalia to Jay-Z. Reviewed by Jeremy Shearmur The Hon. Christian Porter POLICY staff Editor-in-Chief & Publisher: Greg Lindsay Editor: Helen Andrews Assistant Editor: Karla Pincott Design & Production: Ryan Acosta Subscriptions: Kerri Evans and Alicia Kinsey Policy Magazine Ph: +61 2 9438 4377 • Fax: +61 2 9439 7310 Email: [email protected] ISSN: 1032 6634 Please address all advertising enquiries and correspondence to: The Editor Policy PO Box 92 St Leonards NSW 1590 Australia © 2015 The Centre for Independent Studies Limited Level 4, 38 Oxley Street, St Leonards, NSW ABN 15 001 495 012 Cover images: © Dekanaryas | Dreamstime.com Printed by Ligare Pty Ltd Distributed by Gordon & Gotch Australia and Gordon & Gotch New Zealand. -

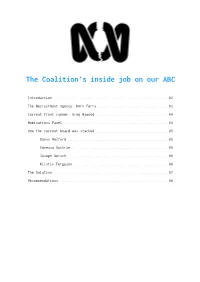

The Coalition's Inside Job on Our

The Coalition’s inside job on our ABC Introduction . . 02 The Recruitment Agency: Korn Ferry . . 03 Current front runner: Greg Hywood . . 04 Nominations Panel . 04 How the current board was stacked . 05 Donny Walford . . 05 Vanessa Guthrie . 05 Joseph Gersch . . 06 Kirstin Ferguson . 06 The Solution . 07 Recommendations . 08 The Coalition’s inside job on our ABC Introduction Since forming government in 2013, the Coalition has waged a public war against our ABC. We’ve witnessed over $337 million in budget cuts,1 blatant attempts to censor and fire journalists for being critical of government policy,2 five hostile government inquiries,3 and an overwhelming vote to privatise the ABC from the Liberal Party Council.4 It’s a level of interference never before seen from a sitting Government towards our public broadcaster. But the Coalition has also attacked our ABC in ways that haven’t been visible, by stacking the ABC Board with their corporate mates, undermining its political independence in the process. We’ve recently witnessed the devastating consequences of this inside job. The Former ABC Chair Justin Milne - an old friend of Malcolm Turnbull - repeatedly sought to interfere in the ABC’s editorial decisions and attempted to force management to fire senior journalists for reporting that angered the Government.5 The rest of the Board chose to ignore these acts of political interference.6 The ABC Board should champion independent journalism and protect reporting from political influence. But it’s increasingly clear that Milne has effectively been acting as an agent of the Coalition Government and the rest of the board have, at the very least, sat on their hands in the face of political interference. -

PRECIS-2018-WEB.Pdf

We must make the building of a free society once more an intellectual adventure, a deed of courage... Unless we can make the philosophic foundations of a free society once more a living intellectual issue, and its implementation a task which challenges the ingenuity and imagination of our liveliest minds, the prospects of freedom are indeed dark. But if we can regain that belief in the power of ideas which was the mark of liberalism at its best, the battle is not lost. — Friedrich Hayek Contents Goals and Aims .................................................. 3 From the Executive Director ............................... 4 Research Programs Education .................................................... 6 FIVE from FIVE literacy program .................. 7 Economics ................................................... 8 Culture, Prosperity & Civil Society ...............10 Scholar-in-Residence ..........................................12 Liberty & Society Student Program ....................13 Consilium ..........................................................15 Events Highlights ...............................................17 Events at a Glance ............................................ 20 Media and Communications ............................. 23 Publications .......................................................24 Fundraising ........................................................27 Research Staff .................................................. 28 Staff ................................................................. 30 Board -

National Museum of Australia Annual Report 2015-16

national museum of australia 15–16 annual report National Museum of Australia 15–16 Annual Report and Audited Financial Statements Department of Communications and the Arts 2 National Museum of Australia Annual Report 15–16 © Commonwealth of Australia 2016 Cover photograph: Maz Banu, Waku performer from ISSN 0818-7142 the Torres Strait, entertains guests at the launch of the Encounters exhibition, 2 December 2015. This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced All photography by George Serras and Jason McCarthy, by any process without prior written permission from the unless otherwise indicated National Museum of Australia. Photographs copyright National Museum of Australia Produced by the National Museum of Australia, Lawson Printed by Union Offset, Canberra Crescent, Acton Peninsula, Canberra Paper used in this report is Impress Satin, a FSC® Mix Requests and enquiries concerning the contents of the certified paper, which ensures that all virgin pulp is derived report should be addressed to: from well-managed forests and controlled sources. It is The Director manufactured by an ISO 14001 certified mill. National Museum of Australia Typeset in Nimbus Sans Novus GPO Box 1901 Canberra ACT 2601 This report is also accessible from the Museum’s website: Telephone: (02) 6208 5000 www.nma.gov.au/annualreport and is available in both Facsimile: 1300 765 587 pdf and html formats. Email: [email protected] 3 Chair’s letter of transmittal Senator the Hon Mitch Fifield Minister for the Arts Parliament House Canberra ACT 2601 Dear Minister On behalf of the Council of the National Museum of Australia, I am pleased to submit our annual report for the financial year ended 30 June 2016. -

Turnbull Blasts SMH Editor-In-Chief Over Anti-Semitic Cartoon

Turnbull blasts SMH editor-in-chief over anti-Semitic cartoon THE AUSTRALIAN AUGUST 04, 2014 12:00AM Sharri Markson Media Editor Sydney Darren Davidson Business Media Writer Sydney An illustration from Nazi propaganda newspaper Der Sturmer in 1934. Source: Supplied COMMUNICATIONS Minister Malcolm Turnbull rang The Sydney Morning Herald’s editor-in-chief , Darren Goodsir, to lambast him for running an anti-Semitic cartoon. And Attorney-General George Brandis likened the cartoon to images from Germany in the 1930s. The Australian can reveal that Mr Turnbull phoned Goodsir during the week to tell him the cartoon was in poor taste. The cartoon, which ran in The Sydney Morning Herald on July 26, shows a Jew with a hooked nose casually destroying Gaza while reclining on a chair. The image, created by illustrator Glen Le Lievre, was complete with a Star of David and also ran on The Age’s website and has not been taken down from online. Mr Turnbull told Goodsir the cartoon had a disturbing similarity with a long and deplorable tradition of anti-Semitic caricatures. It is understood that Mr Turnbull said the cartoon had caused great offence to many of his constituents and that it went well beyond the criticism of Israeli policy in the column by Mike Carlton which the cartoon illustrated. The phone call, made in Mr Turnbull’s capacity as federal member for Wentworth in Sydney’s eastern suburbs, which has a large Jewish population, came as the Heraldwas flooded with complaints from readers about the cartoon and coverage on the conflict in the Middle East. -

The Social and Political Role of the Media

3 The Social and Political 1 Role of the Media INTRODUCTION This chapter introduces some key concepts relating to the social and political role of the media. The chapter considers the ideas of the media as a public sphere and as the fourth estate of government. It also discusses the characteristics of the public, commercial and community sectors in Australian media, and the more recent importance of social media and the internet. The chapter finishes by introducing the contents of this book. In doing so, the concluding paragraphs comment on the regulatory and legal traditions that affect media institutions and how these carry through to contemporary media laws. This chapter surveys territory that has been the subject of intense academic exploration. What follows is a brief introduction to broad themes, but it provides a framework for thinking about media law and policy. 1.1 Social and political The media is often described as an ‘institution’. It is charged with social and political purposes that set it apart from most other types of enterprise. The media provides a forum for public debate. It provides the reporting, analysis and opinion necessary for citizens to make informed political decisions. At its best, it supports investigative journalism that holds powerful people and organisations to account on behalf of the public. The media can mobilise support or opposition around an issue and by doing so drive political action. All of this means the media plays an important role in a liberal democracy. A further purpose of the media is simply to entertain, but this is also important.1 The media we consume shapes our personal and cultural identity. -

Village in the Jungle the Eighth Annual Doireann Macdermott Lecture

Coolabah, No.5, 2011, ISSN 1988-5946, Observatori: Centre d’Estudis Australians, Australian Studies Centre, Universitat de Barcelona Village in the Jungle The Eighth Annual Doireann MacDermott Lecture Baden Offord Copyright©2011 Baden Offord. This text may be archived and redistributed both in electronic form and in hard copy, provided that the author and journal are properly cited and no fee is charged. Editor’s note. This paper is a slightly edited version of a keynote lecture, delivered at the Aula Magna of the University of Barcelona as The Eighth Annual Doireann MacDermott Lecture, organized by the university’s Australian Studies Centre in December 2007. Offord’s essay takes us from Leonard Woolf’s creative and ethical intervention in Britain’s colonial project, forged through a transformative vision of the ‘spirit of place’ in his novel The Village in the Jungle (1931), to the Australian specifics of colonialism and its aftermath. Highly critical of the dominant power structures in Australian society that keep sustaining the Enlightenment discourse of an unfinished colonial project, Offord delineates alternative strategies so as to deal with identity and belonging, arguing for a notion/nation of ‘cultural citizenship’, no longer based on exclusions. Key words: Leonard Woolf; Australian postcoloniality; cultural citizenship Part One During my undergraduate student days of Indian Studies at the University of Sydney I came across one of the most remarkable novels I have ever read, and which to me remains utterly compelling. The Village in the Jungle was written and published by Leonard Woolf (1931). The novel is set in what was then known as Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) and is a gripping story surrounding the plight of husband and wife, Silindu and Dingihami, and their children. -

The Allegations of Political Interference in the Australian Broadcasting Corporation

CPSU Submission: The allegations of political interference in the Australian Broadcasting Corporation CPSU Submission: The allegations of political interference in the Australian Broadcasting Corporation Introductory Statement The Community and Public Sector Union (CPSU) would like to acknowledge and thank the Senators who voted in support of this inquiry. On behalf of CPSU members, we welcome the opportunity to make this submission. The ABC section of the CPSU represents editorial and operational staff employed by the ABC in its content making, technological, administrative and other professional areas. Like many Australians, CPSU members were concerned by the events of September 2018 that gave rise to this inquiry. The ABC is Australia’s most trusted media organisation, much loved by the Australian people. The leadership tensions between the former ABC Managing Director and Chair in September 2018, the role of the ABC Board, and the allegations that have ensued, raise fundamental questions about the governance and independence of the ABC. They also raise questions about the role that the Coalition Government has played given its demonstrated hostility towards the ABC. The independence of the ABC is paramount – it underpins the social contract which the ABC has with the Australian people, and it is what distinguishes the ABC from state media propaganda. The independence of the ABC Chair and ABC Board are paramount too. The people who Australians entrust to hold these positions cannot be political appointments for the government of the day. They are there to serve the 17 million plus Australians who read, watch, listen to and rely on ABC content every week.