Fuck the Border’? Music, Gender and Globalisation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

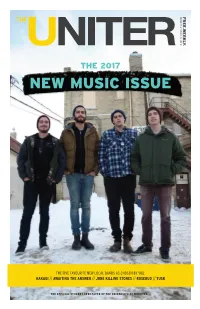

New Music Issue

FREE.WEEKLY. VOLUME VOLUME 71 // ISSUE 16 // JAN 19 THE 2017 NEW MUSIC ISSUE THE FIVE FAVOURITE NEW LOCAL BANDS AS CHOSEN BY YOU: KAKAGI // AWAITING THE ANSWER // JUNE KILLING STONES // ROSEBUD // TUSK THE OFFICIAL STUDENT NEWSPAPER OF THE UNIVERSITY OF WINNIPEG CDI_Uniter_Winnipeg_generic.pdf 1 2017-01-03 1:02 PM ASK ABOUT OUR EVENING CLASSES THAT FIT YOUR SCHEDULE C M a trained Y CM MY professional CY Prepare for an exciting new career in one of our accelerated CMY professional programs and be job ready in less than a year! K Get the skills and experience you need to excel in your field and create your own future. Apply today! 1.800.675.4392 NEWCAREER.CDICOLLEGE.CA Symbol of Courage We’d love to tell you more. Special offer: admission only $5 until January 31, 2017 humanrights.ca #AtCMHR THE UNITER // JANUARY 19, 2017 3 ON THE COVER Kakagi, winners of this year's Uniter Fiver, will headline the showcase at The Good Will Social Club on Jan. 19. SHOW TIME! Before I even get into all the awesome content we’ve gathered together for you in this issue, here’s a final shameless plug for our Uniter Fiver showcase. We’ve got a really great lineup for you on Jan. 19 at The Good Will Social Club: Kakagi, June Killing Stones, Tusk, Rosebud and Awaiting the Answer. Doors are at 8 p.m., show is at 9 p.m., and cover is $10 or $5 with student ID. Come join us and support new local music in Winnipeg! Beyond the show, we’ve got some extended music coverage within these pages for our annual New Music Issue. -

Read Razorcake Issue #27 As A

t’s never been easy. On average, I put sixty to seventy hours a Yesterday, some of us had helped our friend Chris move, and before we week into Razorcake. Basically, our crew does something that’s moved his stereo, we played the Rhythm Chicken’s new 7”. In the paus- IInot supposed to happen. Our budget is tiny. We operate out of a es between furious Chicken overtures, a guy yelled, “Hooray!” We had small apartment with half of the front room and a bedroom converted adopted our battle call. into a full-time office. We all work our asses off. In the past ten years, That evening, a couple bottles of whiskey later, after great sets by I’ve learned how to fix computers, how to set up networks, how to trou- Giant Haystacks and the Abi Yoyos, after one of our crew projectile bleshoot software. Not because I want to, but because we don’t have the vomited with deft precision and another crewmember suffered a poten- money to hire anybody to do it for us. The stinky underbelly of DIY is tially broken collarbone, This Is My Fist! took to the six-inch stage at finding out that you’ve got to master mundane and difficult things when The Poison Apple in L.A. We yelled and danced so much that stiff peo- you least want to. ple with sourpusses on their faces slunk to the back. We incited under- Co-founder Sean Carswell and I went on a weeklong tour with our aged hipster dancing. -

“Punk Rock Is My Religion”

“Punk Rock Is My Religion” An Exploration of Straight Edge punk as a Surrogate of Religion. Francis Elizabeth Stewart 1622049 Submitted in fulfilment of the doctoral dissertation requirements of the School of Language, Culture and Religion at the University of Stirling. 2011 Supervisors: Dr Andrew Hass Dr Alison Jasper 1 Acknowledgements A debt of acknowledgement is owned to a number of individuals and companies within both of the two fields of study – academia and the hardcore punk and Straight Edge scenes. Supervisory acknowledgement: Dr Andrew Hass, Dr Alison Jasper. In addition staff and others who read chapters, pieces of work and papers, and commented, discussed or made suggestions: Dr Timothy Fitzgerald, Dr Michael Marten, Dr Ward Blanton and Dr Janet Wordley. Financial acknowledgement: Dr William Marshall and the SLCR, The Panacea Society, AHRC, BSA and SOCREL. J & C Wordley, I & K Stewart, J & E Stewart. Research acknowledgement: Emily Buningham @ ‘England’s Dreaming’ archive, Liverpool John Moore University. Philip Leach @ Media archive for central England. AHRC funded ‘Using Moving Archives in Academic Research’ course 2008 – 2009. The 924 Gilman Street Project in Berkeley CA. Interview acknowledgement: Lauren Stewart, Chloe Erdmann, Nathan Cohen, Shane Becker, Philip Johnston, Alan Stewart, N8xxx, and xEricx for all your help in finding willing participants and arranging interviews. A huge acknowledgement of gratitude to all who took part in interviews, giving of their time, ideas and self so willingly, it will not be forgotten. Acknowledgement and thanks are also given to Judy and Loanne for their welcome in a new country, providing me with a home and showing me around the Bay Area. -

The Clash and Mass Media Messages from the Only Band That Matters

THE CLASH AND MASS MEDIA MESSAGES FROM THE ONLY BAND THAT MATTERS Sean Xavier Ahern A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2012 Committee: Jeremy Wallach, Advisor Kristen Rudisill © 2012 Sean Xavier Ahern All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Jeremy Wallach, Advisor This thesis analyzes the music of the British punk rock band The Clash through the use of media imagery in popular music in an effort to inform listeners of contemporary news items. I propose to look at the punk rock band The Clash not solely as a first wave English punk rock band but rather as a “news-giving” group as presented during their interview on the Tom Snyder show in 1981. I argue that the band’s use of communication metaphors and imagery in their songs and album art helped to communicate with their audience in a way that their contemporaries were unable to. Broken down into four chapters, I look at each of the major releases by the band in chronological order as they progressed from a London punk band to a globally known popular rock act. Viewing The Clash as a “news giving” punk rock band that inundated their lyrics, music videos and live performances with communication images, The Clash used their position as a popular act to inform their audience, asking them to question their surroundings and “know your rights.” iv For Pat and Zach Ahern Go Easy, Step Lightly, Stay Free. v ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This thesis would not have been possible without the help of many, many people. -

Talking to Songwriters About Copyright and Creativity

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies The Vault: Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2013-01-25 Taking Inspiration: Talking to Songwriters About Copyright and Creativity Hemminger, Peter Hemminger, P. (2013). Taking Inspiration: Talking to Songwriters About Copyright and Creativity (Unpublished master's thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. doi:10.11575/PRISM/27972 http://hdl.handle.net/11023/478 master thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY Taking Inspiration Talking to Songwriters About Copyright and Creativity by Peter Hemminger A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS DEPARTMENT OF COMMUNICATION AND CULTURE CALGARY, ALBERTA JANUARY, 2013 c Peter Hemminger 2013 Abstract In the debate surrounding contemporary approaches to copyright law, the voice of songwriters has been significantly under-represented. This thesis presents the findings of seven interviews with practising Western Canadian singer-songwriters regarding the use of pre-existing intellectual property in their creative process, as well as their understanding of and attitudes towards copyright law. These findings are placed within the context of current theoretical approaches to creativity, and are compared to the beliefs about creativity inherent in current copyright law. -

Campus Life Better Downtown: Barnes

OPEN EVERY DAY I'll MIDNIGHT RECYCLE YOUR MOVIE DVDs ea res CDs, VHS a GAMES TOO IMINGE BUY SELL TRADE • RENT "amnia ' aces CHOOSE FROM OVER 7000 DVDs IN THE VILLAGE 477-5566 movievillage.ca IN THE VILLAGE 475-0077 musictracier.co THEPROJECTORRED RIVER COLLEGE'S NEWSPAPER September 15, 2003 Campus life better downtown: Barnes Fan fights Phase two puts state-of-the-art facilities in a historic setting to bring by Jani Sorensen as directions, program hase two of the Princess description, contact back the Street campus will cir- information, and stu- cumvent the frustration dent advisors. Baxter P says this location students and staff felt last year Jets when construction on the eliminates the William Avenue building fell runaround for the behind schedule, according to student. By Ryan Hladun RRC's director of campus serv- Another design fea- f you are a true Winnipeg ices. ture is the close prox- sports fan, there's a good Ron Barnes says construction imity of the campus' I chance hockey runs of the Princess building and facilities. In the north through your blood. There's the Jubilee Atrium, which joins end of the building, also a good chance the Moose the Princess and William build- along Elgin Avenue, aren't satisfying your hunger ings, was complete by the time students will find the for hockey the way it's meant students returned Sept. 2. He elevator, stairwell, to be played in the 'Peg. You says phase three, the future site water fountains, lock- want the whiteouts, the noise, of the gym, theatre, and radio er carrels, and wash- the thrills - you want your station on Adelaide Street, is rooms on the second, Jets. -

Punk Lyrics and Their Cultural and Ideological Background: a Literary Analysis

Punk Lyrics and their Cultural and Ideological Background: A Literary Analysis Diplomarbeit zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades eines Magisters der Philosophie an der Karl-Franzens Universität Graz vorgelegt von Gerfried AMBROSCH am Institut für Anglistik Begutachter: A.o. Univ.-Prof. Mag. Dr. Hugo Keiper Graz, 2010 TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE 3 INTRODUCTION – What Is Punk? 5 1. ANARCHY IN THE UK 14 2. AMERICAN HARDCORE 26 2.1. STRAIGHT EDGE 44 2.2. THE NINETEEN-NINETIES AND EARLY TWOTHOUSANDS 46 3. THE IDEOLOGY OF PUNK 52 3.1. ANARCHY 53 3.2. THE DIY ETHIC 56 3.3. ANIMAL RIGHTS AND ECOLOGICAL CONCERNS 59 3.4. GENDER AND SEXUALITY 62 3.5. PUNKS AND SKINHEADS 65 4. ANALYSIS OF LYRICS 68 4.1. “PUNK IS DEAD” 70 4.2. “NO GODS, NO MASTERS” 75 4.3. “ARE THESE OUR LIVES?” 77 4.4. “NAME AND ADDRESS WITHHELD”/“SUPERBOWL PATRIOT XXXVI (ENTER THE MENDICANT)” 82 EPILOGUE 89 APPENDIX – Alphabetical Collection of Song Lyrics Mentioned or Cited 90 BIBLIOGRAPHY 117 2 PREFACE Being a punk musician and lyricist myself, I have been following the development of punk rock for a good 15 years now. You might say that punk has played a pivotal role in my life. Needless to say, I have also seen a great deal of media misrepresentation over the years. I completely agree with Craig O’Hara’s perception when he states in his fine introduction to American punk rock, self-explanatorily entitled The Philosophy of Punk: More than Noise, that “Punk has been characterized as a self-destructive, violence oriented fad [...] which had no real significance.” (1999: 43.) He quotes Larry Zbach of Maximum RockNRoll, one of the better known international punk fanzines1, who speaks of “repeated media distortion” which has lead to a situation wherein “more and more people adopt the appearance of Punk [but] have less and less of an idea of its content. -

2008/2009 Annual Report

Manitoba is overjoyed to announce the rebirth of Manitoba Film & Sound Manitoba Film & Music on January 1, 2009 continuing to make fi lm and music flourish in Manitoba Letter of Transmittal July 31, 2009 Honourable Eric Robinson Minister of Culture, Heritage, Tourism and Sport Room 118, Legislative Building 450 Broadway Winnipeg, Manitoba R3C 0V8 Dear Minister Robinson: In accordance with Section 16 of the Manitoba Film and Sound Recording Development Corporation Act, I have the honour to present the Annual Report of the Manitoba Film and Sound Recording Development Corporation for the fi scal year ended March 31, 2009. Respectfully submitted, David Dandeneau Chairperson Table of Contents Message ...............................................4 The Corporation ....................................... 7 Manitoba Film & Music Showcase 2009 ........ 8 Year in Review ........................................10 Production Activity ....................................16 Tax Credit ............................................. 16 Front Cover: The following are all MANITOBA FILM & MUSIC Other Dollars Levered ...............................17 supported artists and projects. TOP ROW (L - R): Promotional poster for the feature fi lm Amreeka • Twilight Hotel • The Perms • The Juries ...................................................18 Details • Alana Levandoski • Promotional poster for feature fi lm, The Haunting in Connecticut • BOTTOM ROW (L - R): Promotional Film Projects Supported .............................18 poster for Feature Film New in Town -

Coachella 2010 Strike Anywhere

SPECIAL FIRST ISSUE COACHELLA 2010 RACKET’S PICKS, REUNIONS, & FESTIVAL TIPS EXCLUSIVE INTERVIEW STRIKE ANYWHERE PLUS ADVENTURE TIME SHITTY BEER E-READERS SPRINGRACKET MAGAZINE 20101 2 RACKET MAGAZINE RACKET MAGAZINE 3 LETTER FROM THE CONTENTS THE EMPEROR SPRING 2010 Hello there! FEATURES COACHELLA 07 KIDS CAN EAT A BAG OF DICKS 30 FESTIVAL DO’S AND DONT’S My name’s The Emperor, and I’m supposed to welcome you to Racket but as I’m a terrible host, just RacketJeff discusses A Wilhelm Scream’s return. How to avoid chaffing, sunburns help yourself, look around, poke your nose into our closets and go through our underwear drawers. and blisters Hopefully you’re enticed rather than terrified. 16 BEST OF THE WORST Still here? Good. I wanted to get rid of the prudes, and hopefully they’re gone so now we can cut the The least shitty of shitty beers 33 REUNITED AND IT FEELS shit and get down to business. Racket business. For five years now we have been sucking up valuable SO GOOD space on the Internet to make room for our own brand of irreverent artist interviews and sometimes 20 TOP 10 SOLO ARTISTS Well, well, look who’s back deplorable journalistic integrity. If you’ve ever wanted to hear political punks tell an offensive joke or Notice how none of these a TV personality threaten the writer, you’ve come to the right place. are the bass players? 34 WHO TO WATCH Racket’s writers pick their favs to watch We’re not the next big thing in media, so don’t go getting your hopes up, but we are hear to try to 23 make with the funny. -

SAC Winter 2007

Executive Director’s Message EDITOR Nick Krewen Setting S.A.C. Sights on Sites, MANAGING EDITOR Beverly Hardy LAYOUT Lori Veljkovic Sounds and Songposium COPY EDITOR Leah Erbe s fall fades into winter, I'm extremely itally is an advantage for those who want to ensure Canadian Publications Mail Agreement pleased to announce that a number of dif- their music is “out there” for the world to hear. No. 40014605 ferent S.A.C. programs will be warming up The S.A.C. was also present at a number of Canada Post Account No. 02600951 A ISSN 1481-3661 ©2002 songwriters as we head into the colder months -- important conferences. The first, Copycamp, some familiar, some new and all of them an involved a three-day session in Toronto Songwriters Association of Canada opportunity to encourage your creativity and September 28-30 that exposed all types of Subscriptions: Canada $16/year plus sharpen your business acumen. creators to various copyright challenges and GST; USA/Foreign $22 options facing the world today. First, I'm very pleased to announce that Songwriters Magazine is a publication of the Songposium 2.0 is taking place in five cities across The other was the Future of Music Policy Songwriters Association of Canada (S.A.C.) the country, targeting the urban, country and pop Summit, held in Montreal during the POP and is published four times a year. Members music fields. Montreal festival October 5-7. Both events offered of S.A.C. receive Songwriters Magazine as Featuring some amazing industry professionals excellent information on directions the music part of their membership. -

Pop Goes to War, 2001–2004:U.S. Popular Music After 9/11

1 POP GOES TO WAR, 2001–2004: U.S. POpuLAR MUSIC AFTER 9/11 Reebee Garofalo Mainstream popular music in the United States has always provided a window on national politics. The middle-of-the-road sensibilities of Tin Pan Alley told us as much about societal values in the early twentieth century as rock and roll’s spirit of rebellion did in the fifties and sixties. To cite but one prominent example, as the war in Vietnam escalated in the mid-sixties, popular music provided something of a national referendum on our involvement. In 1965 and 1966, while the nation was sorely divided on the issue, both the antiwar “Eve of Destruction” by Barry McGuire and the military ode “The Ballad of the Green Berets” by Barry Sadler hit number one within months of each other. As the war dragged on through the Nixon years and military victory seemed more and more remote, however, public opinion began to turn against the war, and popular music became more and more clearly identified with the antiwar movement. Popular music—and in particular, rock—has nonetheless served con- tradictory functions in American history. While popular music fueled opposition to the Vietnam War at home, alienated, homesick GIs eased the passage of time by blaring those same sounds on the battlefield (as films such as Apocalypse Now and Good Morning, Vietnam accurately document). Rock thus was not only the soundtrack of domestic opposition to the war; it was the soundtrack of the war itself. This phenomenon was not wasted on military strategists, who soon began routinely incorporat- ing music into U.S. -

Type Artist Album Barcode Price 32.95 21.95 20.95 26.95 26.95

Type Artist Album Barcode Price 10" 13th Floor Elevators You`re Gonna Miss Me (pic disc) 803415820412 32.95 10" A Perfect Circle Doomed/Disillusioned 4050538363975 21.95 10" A.F.I. All Hallow's Eve (Orange Vinyl) 888072367173 20.95 10" African Head Charge 2016RSD - Super Mystic Brakes 5060263721505 26.95 10" Allah-Las Covers #1 (Ltd) 184923124217 26.95 10" Andrew Jackson Jihad Only God Can Judge Me (white vinyl) 612851017214 24.95 10" Animals 2016RSD - Animal Tracks 018771849919 21.95 10" Animals The Animals Are Back 018771893417 21.95 10" Animals The Animals Is Here (EP) 018771893516 21.95 10" Beach Boys Surfin' Safari 5099997931119 26.95 10" Belly 2018RSD - Feel 888608668293 21.95 10" Black Flag Jealous Again (EP) 018861090719 26.95 10" Black Flag Six Pack 018861092010 26.95 10" Black Lips This Sick Beat 616892522843 26.95 10" Black Moth Super Rainbow Drippers n/a 20.95 10" Blitzen Trapper 2018RSD - Kids Album! 616948913199 32.95 10" Blossoms 2017RSD - Unplugged At Festival No. 6 602557297607 31.95 (45rpm) 10" Bon Jovi Live 2 (pic disc) 602537994205 26.95 10" Bouncing Souls Complete Control Recording Sessions 603967144314 17.95 10" Brian Jonestown Massacre Dropping Bombs On the Sun (UFO 5055869542852 26.95 Paycheck) 10" Brian Jonestown Massacre Groove Is In the Heart 5055869507837 28.95 10" Brian Jonestown Massacre Mini Album Thingy Wingy (2x10") 5055869507585 47.95 10" Brian Jonestown Massacre The Sun Ship 5055869507783 20.95 10" Bugg, Jake Messed Up Kids 602537784158 22.95 10" Burial Rodent 5055869558495 22.95 10" Burial Subtemple / Beachfires 5055300386793 21.95 10" Butthole Surfers Locust Abortion Technician 868798000332 22.95 10" Butthole Surfers Locust Abortion Technician (Red 868798000325 29.95 Vinyl/Indie-retail-only) 10" Cisneros, Al Ark Procession/Jericho 781484055815 22.95 10" Civil Wars Between The Bars EP 888837937276 19.95 10" Clark, Gary Jr.