Climate Change Effects in El Yunque National Forest, Puerto Rico, and The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Climatology of Tropical Cyclone Rainfall Over

CLIMATOLOGY OF TROPICAL CYCLONE RAINFALL OVER PUERTO RICO: PROCESSES, PATTERNS AND IMPACTS By JOSÉ JAVIER HERNÁNDEZ AYALA A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2016 1 © 2016 José Javier Hernández Ayala 2 To my beloved Puerto Rico, its atmosphere, environment and people 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The main ideas behind the development of this dissertation came from multiple experiences with tropical cyclones while living in Puerto Rico. Those life experiences motivated me to explore the climate of the tropics, with special attention to the rainfall associated with those extreme events and their role in Puerto Rico’s physical geography. The research conducted in this dissertation was possible from support of Dr. Corene Matyas, Associate Professor and Graduate Coordinator at the Department of Geography at the University of Florida. Her magnificent mentoring and continuous support enable me to invest the necessary effort and time to complete this dissertation. I am truly grateful for her exceptional role as my committee chair. I want to thank Dr. Peter Waylen for his continuous support and all of the inspiring conversations we’ve had about research and life in general that gave me even more strength to continue in this journey towards the PhD. I thank Dr. Timothy Fik for sharing his expertise in quantitative methods through two great courses and for inspiring me to aspire to more in life. Thanks to Dr. Zhong-Ren Peng for being my external committee member and teaching me more about the human dimension of climate related phenomena. -

3.44 ,L Regional Director, U.S.{Fisl1 a D Wildlife Service

RECOVERY PLAN for Pleodendron macranthum and Eugenia haematocarpa Prepared by Kenneth W. Foote Bequerdn Field Office US. Fish and Wildlife Service Boquerbn, Puerto Rico for the US. Fish and Wildlife Service Southeast Region Atlanta, Georgia 3.44 ,L Regional Director, U.S.{Fisl1 a d Wildlife Service Date: DISCLAIMER Recovery Plans delineate reasonable actions which are believed to be required to recover and/or protect species. Plans are published by the US. Fish and Wildlife Service, sometimes prepared with the assistance of recovery teams, contractors, State (Commonwealth) agencies, and others. Plans are reviewed by the public and submitted to additional peer review before they are adopted by the Service. Objectives will be attained and any necessary funds made available subject to and other constraints the involved as as to budgetary affecting parties , well the need address other priorities- Recovery plans do not obligate other parties to undertake specific tasks and may not represent the views or the official positions or approval of any individuals or agencies involved in formulating the plan, other then the US. Fish and Wildlife Service. Recovery plans represent the official position of the US. Fish and Wildlife Service only after they have been signed by the Regional Director or Director as approved. Approved recovery plans are subject to modification as dictated by new findings, changes in species status, and the completion of recovery tasks. By approving this document, the Regional Director certifies that the data used in its development represent the best scientific and commercial data available at the time it was written. Copies of all documents reviewed in the development of the plan are available in the administrative record, located at the Boqueron Field Office. -

Testing Sustainable Forestry Methods in Puerto Rico

Herpetology Notes, volume 8: 141-148 (2015) (published online on 10 April 2015) Testing sustainable forestry methods in Puerto Rico: Does the presence of the introduced timber tree Blue Mahoe, Talipariti elatum, affect the abundance of Anolis gundlachi? Norman Greenhawk Abstract. The island of Puerto Rico has one of the highest rates of regrowth of secondary forests largely due to abandonment of previously agricultural land. The study was aimed at determining the impact of the presence of Talipariti elatum, a timber species planted for forest enrichment, on the abundance of anoles at Las Casas de la Selva, a sustainable forestry project located in Patillas, Puerto Rico. The trees planted around 25 years ago are fast-growing and now dominate canopies where they were planted. Two areas, a control area of second-growth forest without T. elatum and an area within the T. elatum plantation, were surveyed over an 18 month period. The null hypothesis that anole abundance within the study areas is independent of the presence of T. elatum could not be rejected. The findings of this study may have implications when designing forest management practices where maintaining biodiversity is a goal. Keywords. Anolis gundlachi, Anolis stratulus, Puerto Rican herpetofauna, introduced species, forestry Introduction The secondary growth forest represents a significant resource base for the people of Puerto Rico, and, if At the time of Spanish colonization in 1508, nearly managed properly, an increase in suitable habitat one hundred percent of Puerto Rico was covered in for forest-dwelling herpetofauna. Depending on the forest (Wadsworth, 1950). As a result of forest clearing management methods used, human-altered agro- for agricultural and pastureland, ship building, and fuel forestry plantations have potential conservation wood, approximately one percent of the land surface value (Wunderle, 1999). -

Monocotyledons and Gymnosperms of Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands

SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION Contributions from the United States National Herbarium Volume 52: 1-415 Monocotyledons and Gymnosperms of Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands Editors Pedro Acevedo-Rodríguez and Mark T. Strong Department of Botany National Museum of Natural History Washington, DC 2005 ABSTRACT Acevedo-Rodríguez, Pedro and Mark T. Strong. Monocots and Gymnosperms of Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands. Contributions from the United States National Herbarium, volume 52: 415 pages (including 65 figures). The present treatment constitutes an updated revision for the monocotyledon and gymnosperm flora (excluding Orchidaceae and Poaceae) for the biogeographical region of Puerto Rico (including all islets and islands) and the Virgin Islands. With this contribution, we fill the last major gap in the flora of this region, since the dicotyledons have been previously revised. This volume recognizes 33 families, 118 genera, and 349 species of Monocots (excluding the Orchidaceae and Poaceae) and three families, three genera, and six species of gymnosperms. The Poaceae with an estimated 89 genera and 265 species, will be published in a separate volume at a later date. When Ackerman’s (1995) treatment of orchids (65 genera and 145 species) and the Poaceae are added to our account of monocots, the new total rises to 35 families, 272 genera and 759 species. The differences in number from Britton’s and Wilson’s (1926) treatment is attributed to changes in families, generic and species concepts, recent introductions, naturalization of introduced species and cultivars, exclusion of cultivated plants, misdeterminations, and discoveries of new taxa or new distributional records during the last seven decades. -

Phylogeny, Ecomorphological Evolution, and Historical Biogeography of the Anolis Cristatellus Series

Uerpetological Monographs, 18, 2004, 90-126 © 2004 by The Herpetologists' League, Inc. PHYLOGENY, ECOMORPHOLOGICAL EVOLUTION, AND HISTORICAL BIOGEOGRAPHY OF THE ANOLIS CRISTATELLUS SERIES MATTHEW C. BRANDLEY^''^'"' AND KEVIN DE QUEIROZ^ ^Sam Noble Oklahoma Museum of Natural History and Department of Zoology, The University of Oklahoma, Norman, OK 73072, USA ^Department of Zoology, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC 20,560, USA ABSTRACT: TO determine the evolutionary relationships within the Anolis cristatellus series, we employed phylogenetic analyses of previously published karyotype and allozyme data as well as newly collected morphological data and mitochondrial DNA sequences (fragments of the 12S RNA and cytochrome b genes). The relationships inferred from continuous maximum likelihood reanalyses of allozyme data were largely poorly supported. A similar analysis of the morphological data gave strong to moderate support for sister relationships of the two included distichoid species, the two trunk-crown species, the grass-bush species A. poncensis and A. pulchellus, and a clade of trunk-ground and grass-bush species. The results of maximum likelihood and Bayesian analyses of the 12S, cyt b, and combined mtDNA data sets were largely congruent, but nonetheless exhibit some differences both with one another and with those based on the morphological data. We therefore took advantage of the additive properties of likelihoods to compare alternative phylogenetic trees and determined that the tree inferred from the combined 12S and cyt b data is also the best estimate of the phylogeny for the morphological and mtDNA data sets considered together. We also performed mixed-model Bayesian analyses of the combined morphology and mtDNA data; the resultant tree was topologically identical to the combined mtDNA tree with generally high nodal support. -

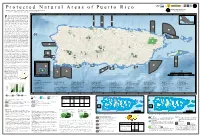

Protected Areas by Management 9

Unted States p Forest Department a Service DRNA of Agriculture g P r o t e c t e d N a t u r a l A r e a s o f P u e r to R i c o K E E P I N G C O M M ON S P E C I E S C O M M O N PRGAP ANALYSIS PROJECT William A. Gould, Maya Quiñones, Mariano Solórzano, Waldemar Alcobas, and Caryl Alarcón IITF GIS and Remote Sensing Lab A center for tropical landscape analysis U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, International Institute of Tropical Forestry . o c 67°30'0"W 67°20'0"W 67°10'0"W 67°0'0"W 66°50'0"W 66°40'0"W 66°30'0"W 66°20'0"W 66°10'0"W 66°0'0"W 65°50'0"W 65°40'0"W 65°30'0"W 65°20'0"W i R o t rotection of natural areas is essential to conserving biodiversity and r e u P maintaining ecosystem services. Benefits and services provided by natural United , Protected areas by management 9 States 1 areas are complex, interwoven, life-sustaining, and necessary for a healthy A t l a n t i c O c e a n 1 1 - 6 environment and a sustainable future (Daily et al. 1997). They include 2 9 0 clean water and air, sustainable wildlife populations and habitats, stable slopes, The Bahamas 0 P ccccccc R P productive soils, genetic reservoirs, recreational opportunities, and spiritual refugia. -

In the Face of Accelerating Habitat Loss and an Increasing Human

ABSTRACT Borkhataria, Rena Rebecca. Ecological and Political Implications of Conversion from Shade to Sun Coffee in Puerto Rico. (Under the direction of Jaime Collazo.) Recent studies have shown that biodiversity is greater in shaded plantations than in sun coffee plantations, yet many farmers are converting to sun coffee varieties to increase short-term yields or to gain access to economic incentives. Through conversion, ecosystem complexity may be reduced and ecological services rendered by inhabitants may be lost. I attempted to quantify differences in abundances and diversity of predators in sun and shade coffee plantations in Puerto Rico and to gain insight into the ecological services they might provide. I also interviewed coffee farmers to determine the factors influencing conversion to sun coffee in Puerto Rico and to examine their attitudes toward the conservation of wildlife. Avian abundances were significantly higher in shaded coffee than in sun (p = 0.01) as were the number of species (p = 0.09). Avian species that were significantly more abundant in shaded coffee tended to be insectivorous, whereas those in sun coffee were granivorous. Lizard abundances (all species combined) did not differ significantly between plantations types, but Anolis stratulus was more abundant in sun plantations and A. gundlachi and A. evermanni were present only in shaded plantations. Insect abundances (all species combined) were significantly higher in shaded coffee (p = 0.02). I used exclosures in a shaded coffee plantation to examine the effects of vertebrate predators on the arthropods associated with coffee, in particular the coffee leaf miner (Leucoptera coffeela) and the flatid planthopper Petrusa epilepsis, in a shaded coffee plantation in Puerto Rico. -

To See Our Puerto Rico Vacation Planning

DISCOVER PUERTO RICO LEISURE + TRAVEL 2021 Puerto Rico Vacation Planning Guide 1 IT’S TIME TO PLAN FOR PUERTO RICO! It’s time for deep breaths and even deeper dives. For simple pleasures, dramatic sunsets and numerous ways to surround yourself with nature. It’s time for warm welcomes and ice-cold piña coladas. As a U.S. territory, Puerto Rico offers the allure of an exotic locale with a rich, vibrant culture and unparalleled natural offerings, without needing a passport or currency exchange. Accessibility to the Island has never been easier, with direct flights from domestic locations like New York, Charlotte, Dallas, and Atlanta, to name a few. Lodging options range from luxurious beachfront resorts to magical historic inns, and everything in between. High standards of health and safety have been implemented throughout the Island, including local measures developed by the Puerto Rico Tourism Company (PRTC), alongside U.S. Travel Association (USTA) guidelines. Outdoor adventures will continue to be an attractive alternative for visitors looking to travel safely. Home to one of the world’s largest dry forests, the only tropical rainforest in the U.S. National Forest System, hundreds of underground caves, 18 golf courses and so much more, Puerto Rico delivers profound outdoor experiences, like kayaking the iridescent Bioluminescent Bay or zip lining through a canopy of emerald green to the sound of native coquí tree frogs. The culture is equally impressive, steeped in European architecture, eclectic flavors of Spanish, Taino and African origins and a rich history – and welcomes visitors with genuine, warm Island hospitality. Explore the authentic local cuisine, the beat of captivating music and dance, and the bustling nightlife, which blended together, create a unique energy you won’t find anywhere else. -

2011 Vol. 14, Issue 3

Department of Botany & the U.S. National Herbarium The Plant Press New Series - Vol. 14 - No. 3 July-September 2011 Island Explorations and Evolutionary Investigations By Vinita Gowda or over a century the Caribbean eastward after the Aves Ridge was formed On joining the graduate program region, held between North and to the West. Although the Lesser Antilles at The George Washington University FSouth America, has been an active is commonly referred to as a volcani- in Washington, D.C., in the Fall of area of research for people with interests cally active chain of islands, not all of the 2002, I decided to investigate adapta- in island biogeography, character evolu- Lesser Antilles is volcanic. Based on geo- tion in plant-pollinator interactions tion, speciation, as well as geology. Most logical origin and elevation all the islands using a ‘multi-island’ comparative research have invoked both dispersal and of the Lesser Antilles can be divided into approach using the Caribbean Heliconia- vicariance processes to explain the distri- two groups: a) Limestone Caribbees (outer hummingbird interactions as the study bution of the local flora and fauna, while arc: calcareous islands with a low relief, system. Since I was interested in under- ecological interactions such as niche dating to middle Eocene to Pleistocene), standing factors that could influence partitioning and ecological adaptations and b) Volcanic Caribbees (inner arc: plant-pollinator mutualistic interactions have been used to explain the diversity young volcanic islands with strong relief, between the geographically distinct within the Caribbean region. One of dating back to late Miocene). islands, I chose three strategic islands of the biggest challenges in understanding the Lesser Antilles: St. -

Guide to Theecological Systemsof Puerto Rico

United States Department of Agriculture Guide to the Forest Service Ecological Systems International Institute of Tropical Forestry of Puerto Rico General Technical Report IITF-GTR-35 June 2009 Gary L. Miller and Ariel E. Lugo The Forest Service of the U.S. Department of Agriculture is dedicated to the principle of multiple use management of the Nation’s forest resources for sustained yields of wood, water, forage, wildlife, and recreation. Through forestry research, cooperation with the States and private forest owners, and management of the National Forests and national grasslands, it strives—as directed by Congress—to provide increasingly greater service to a growing Nation. The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, disability, and where applicable sex, marital status, familial status, parental status, religion, sexual orientation genetic information, political beliefs, reprisal, or because all or part of an individual’s income is derived from any public assistance program. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TDD).To file a complaint of discrimination, write USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, 1400 Independence Avenue, S.W. Washington, DC 20250-9410 or call (800) 795-3272 (voice) or (202) 720-6382 (TDD). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. Authors Gary L. Miller is a professor, University of North Carolina, Environmental Studies, One University Heights, Asheville, NC 28804-3299. -

What Happened to Ponce

Reconstructing early modern disaster management in Puerto Rico: development and planning examined through the lens of Hurricanes San Ciriaco (1899), San Felipe (1928) and Santa Clara (1956) Ingrid Olivo Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy under the Executive Committee of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2015 © 2015 Ingrid Olivo All rights reserved ABSTRACT Reconstructing early modern disaster management in Puerto Rico: development and planning examined through the lens of Hurricanes San Ciriaco (1899), San Felipe (1928) and Santa Clara (1956) Ingrid Olivo This is the first longitudinal, retrospective, qualitative, descriptive and multi-case study of hurricanes in Puerto Rico, from 1899 to 1956, researching for planning purposes the key lessons from the disaster management changes that happened during the transition of Puerto Rico from a Spanish colony to a Commonwealth of the United States. The selected time period is crucial to grasp the foundations of modern disaster management, development and planning processes. Disasters are potent lenses through which inspect realpolitik in historical and current times, and grasp legacies that persist today, germane planning tasks. Moreover, Puerto Rico is an exemplary case; it has been an experimental laboratory for policies later promoted by the US abroad, and it embodies key common conditions to develop my research interface between urban planning and design, meteorology, hydrology, sociology, political science, culture and social history. After introducing the dissertation, I present a literature review of the emergence of the secular characterization of disasters and a recent paradigm shift for understanding what a disaster is, its causes and how to respond. -

Evolutionary Relationships and Historical Biogeography of Anolis

Journal of Biogeography (J. Biogeogr.) (2007) 34, 1546–1558 ORIGINAL Evolutionary relationships and historical ARTICLE biogeography of Anolis desechensis and Anolis monensis, two lizards endemic to small islands in the eastern Caribbean Sea Javier A. Rodrı´guez-Robles1*, Tereza Jezkova1 and Miguel A. Garcı´a2 1School of Life Sciences, University of Nevada, ABSTRACT Las Vegas, NV 89154-4004, USA, 2Division of Aim We investigated the evolutionary relationships and historical biogeography Wildlife, Department of Natural and Environmental Resources, PO Box 366147, San of two lizard species (Anolis desechensis and Anolis monensis) endemic to small Juan, Puerto Rico 00936-6147, USA oceanic islands in the eastern Caribbean Sea. Location Desecheo, Mona and Monito Islands, in the Mona Passage, and Puerto Rico, eastern Caribbean Sea. Methods We reconstructed the phylogenetic relationships of A. desechensis and A. monensis from DNA sequences of two mitochondrial genes using maximum likelihood, Bayesian inference and maximum parsimony methods. The ingroup included species from Puerto Rico (Anolis cooki, Anolis cristatellus), the Bahamas (Anolis scriptus), and the British Virgin Islands (Anolis ernestwilliamsi). We also constructed a median-joining mutational network to visualize relationships among the haplotypes of A. cooki and A. monensis from Mona and Monito Islands. Results The three phylogenetic methods suggested the same pattern of relationships. Anolis desechensis nests within A. cristatellus, and is most closely related to A. cristatellus from south-western Puerto Rico. Our analyses also indicated that A. monensis is the sister species of A. cooki, an anole restricted to the south-western coast of Puerto Rico. Although they are closely related, the populations of A.