Racist Disinformation on the Web: the Role of Anti- Racist Sites in Providing Balance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download (2399Kb)

A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of Warwick Permanent WRAP URL: http://wrap.warwick.ac.uk/ 84893 Copyright and reuse: This thesis is made available online and is protected by original copyright. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item for information to help you to cite it. Our policy information is available from the repository home page. For more information, please contact the WRAP Team at: [email protected] warwick.ac.uk/lib-publications Culture is a Weapon: Popular Music, Protest and Opposition to Apartheid in Britain David Toulson A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History University of Warwick Department of History January 2016 Table of Contents Acknowledgements………………………………………………………………...iv Declaration………………………………………………………………………….v Abstract…………………………………………………………………………….vi Introduction………………………………………………………………………..1 ‘A rock concert with a cause’……………………………………………………….1 Come Together……………………………………………………………………...7 Methodology………………………………………………………………………13 Research Questions and Structure…………………………………………………22 1)“Culture is a weapon that we can use against the apartheid regime”……...25 The Cultural Boycott and the Anti-Apartheid Movement…………………………25 ‘The Times They Are A Changing’………………………………………………..34 ‘Culture is a weapon of struggle’………………………………………………….47 Rock Against Racism……………………………………………………………...54 ‘We need less airy fairy freedom music and more action.’………………………..72 2) ‘The Myth -

The Effect of Social Media on Perceptions of Racism, Stress Appraisal, and Anger Expression Among Young African American Adults

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2016 Rage and social media: The effect of social media on perceptions of racism, stress appraisal, and anger expression among young African American adults Morgan Maxwell Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd Part of the Health Psychology Commons, and the Social Psychology Commons © The Author Downloaded from https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd/4311 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RAGE AND SOCIAL MEDIA USE: THE EFFECT OF SOCIAL MEDIA CONSUMPTION ON PERCEIVED RACISM, STRESS APPRAISAL, AND ANGER EXPRESSION AMONG YOUNG AFRICAN AMEIRCAN ADULTS A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Virginia Commonwealth University By: MORGAN LINDSEY MAXWELL Bachelor of Science, Howard University, 2008 Master of Science, Vanderbilt University, 2010 Master of Science, Virginia Commonwealth University, 2013 Director: Faye Z. Belgrave, Ph.D. Professor of Psychology Department of Psychology Virginia Commonwealth University Richmond, Virginia April 18, 2016 ii Acknowledgements “No matter what accomplishments you make, somebody helped you”. -Althea Gibson To my mother and father Renee and Cedric Maxwell, to my soul sister Dr. Jasmine Abrams, to my loving friends and supportive family, to my committee members (Dr. Eric Benotsch, Dr. Joann Richardson, Dr. Shawn Utsey, and Dr. Linda Zyzniewski), to my incredible mentor and second mother Dr. -

Cultural Politics and Old and New Social Movements

P1: FHD/IVO/LCT P2: GCR/LCT QC: Qualitative Sociology [quso] ph132-quas-375999 June 13, 2002 19:33 Style file version June 4th, 2002 Qualitative Sociology, Vol. 25, No. 3, Fall 2002 (C 2002) Music in Movement: Cultural Politics and Old and New Social Movements Ron Eyerman1 After a period of interdisciplinary openness, contemporary sociology has only re- cently rediscovered culture. This is especially true of political sociology, where institutional and network analyses, as well as rational choice models, have dom- inated. This article will offer another approach by focusing on the role of music and the visual arts in relation to the formation of collective identity, collective memory and collective action. Drawing on my own research on the Civil Rights movement in the United States and the memory of slavery in the formation of African-American identity, and its opposite, the place of white power music in contemporary neo-fascist movements, I will outline a model of culture as more than a mobilization resource and of the arts as political mediators. KEY WORDS: social movements; representation; performance. COLLECTIVE BEHAVIOR: CULTURE AND POLITICS The study of collective behavior has traditionally included the study of sub- cultures and social movements as central elements. This was so from the beginning when the research field emerged in the disciplinary borderlands between sociology and psychology in the periods just before and after World War II. Using a scale of rationality, the collective behaviorist placed crowd behavior at the most irra- tional end of a continuum and social movements at the most rational. The middle ground was left for various cults and subcultures, including those identified with youth. -

Liberal Women: a Proud History

<insert section here> | 1 foreword The Liberal Party of Australia is the party of opportunity and choice for all Australians. From its inception in 1944, the Liberal Party has had a proud LIBERAL history of advancing opportunities for Australian women. It has done so from a strong philosophical tradition of respect for competence and WOMEN contribution, regardless of gender, religion or ethnicity. A PROUD HISTORY OF FIRSTS While other political parties have represented specific interests within the Australian community such as the trade union or environmental movements, the Liberal Party has always proudly demonstrated a broad and inclusive membership that has better understood the aspirations of contents all Australians and not least Australian women. The Liberal Party also has a long history of pre-selecting and Foreword by the Hon Kelly O’Dwyer MP ... 3 supporting women to serve in Parliament. Dame Enid Lyons, the first female member of the House of Representatives, a member of the Liberal Women: A Proud History ... 4 United Australia Party and then the Liberal Party, served Australia with exceptional competence during the Menzies years. She demonstrated The Early Liberal Movement ... 6 the passion, capability and drive that are characteristic of the strong The Liberal Party of Australia: Beginnings to 1996 ... 8 Liberal women who have helped shape our nation. Key Policy Achievements ... 10 As one of the many female Liberal parliamentarians, and one of the A Proud History of Firsts ... 11 thousands of female Liberal Party members across Australia, I am truly proud of our party’s history. I am proud to be a member of a party with a The Howard Years .. -

Hate and the Internet by Kenneth S. Stern Kenneth S. Stern Is the American Jewish Committee's Specialist on Antisemitism and E

Hate and the Internet by Kenneth S. Stern Kenneth S. Stern is the American Jewish Committee’s specialist on antisemitism and extremism. Introduction For ten or twenty dollars a month, you can have a potential audience of tens of millions of people. There was a time when these folks were stuck surreptitiously putting fliers under your windshield wiper. Now they are taking the same material and putting it on the Internet." – Ken McVay[i] Visit any archive on hate and extremism and you will find a treasure trove of books, newspapers, magazines and newsletters. If you are lucky enough to find original mailers, many will be plain brown or manila wrappings, designed to protect the recipient from inquisitive neighbors and postal workers. If the archive includes material from the 1980s and early 1990s, it likely contains videotapes and radio programs, maybe even dial-a-hate messages from "hot line" answering machines. It may also house faxed "alerts" that were broadcast to group members with the push of one button, in place of old-fashioned telephone "trees." Supporters of the Branch Davidians at Waco used faxes, as did groups involved in some militia confrontations. Today’s hate groups still mail newsletters, print books, produce videos and radio programs, have message "hot lines," fax alerts and, yes, put fliers under windshield wipers. But they increasingly rely on the Internet. Hate groups understand that this global computer network is far superior to the other modes of communication. Even in its infancy — for the ’net is still being defined — it is already what CDs are to records, and may, for many, become what electricity was to gaslight. -

The Realities of Homegrown Hate

1 of 5 The Realities of Homegrown Hate Jessie Daniels, Cyber Racism: White Supremacy Online and the New Attack on Civil Rights (Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, 2009), 274 pp. Robert Futrell and Pete Simi, American Swastika: Inside the White Power Movement’s Hidden Spaces of Hate (Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, 2010), 184 pp. Reviewer: Robin Gorsline [email protected] A few months ago, the United States Supreme Court handed down its decision in Snyder v. Phelps. By an 8-1 vote, the court ringingly reaffirmed freedom of speech for a hate group. The case and the decision elicited great interest for at least two reasons: the hate group identifies itself as a Christian church—Westboro Baptist Church of Topeka, KS—and the speech at issue was a protest at the funeral for a soldier killed in the line of duty in Iraq. An observer from another planet might think, based on news coverage of the group and the event, that such speech is unusual. Admittedly, there are few, if any, other groups protesting at military funerals, but the fact of hate speech—and specifically speech spewing forth hate toward Jews, African Americans, and LGBT people—is real in the United States. Two books—Cyber Racism: White Supremacy Online and the New Attack on Civil Rights and American Swastika: Inside the White Power Movement’s Hidden Spaces of Hate—remind us of this reality in powerful ways. They also raise real issues about free speech and community life, particularly as the United States seems to uphold markedly different values from much of the rest of the world. -

White Noise Music - an International Affair

WHITE NOISE MUSIC - AN INTERNATIONAL AFFAIR By Ms. Heléne Lööw, Ph.D, National Council of Crime Prevention, Sweden Content Abstract............................................................................................................................................1 Screwdriver and Ian Stuart Donaldson............................................................................................1 From Speaker to Rock Star – White Noise Music ..........................................................................3 Ideology and music - the ideology of the white power world seen through the music...................4 Zionist Occupational Government (ZOG).......................................................................................4 Heroes and martyrs........................................................................................................................12 The Swedish White Noise Scene...................................................................................................13 Legal aspects .................................................................................................................................15 Summary........................................................................................................................................16 Abstract Every revolutionary movement has its own music, lyrics and poets. The music in itself does not create organisations nor does the musicians themselves necessarily lead the revolution. But the revolutionary/protest music create dreams, -

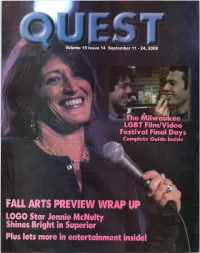

View Entire Issue As

Volume 15 Issue 14 September 11 - 24, 2008 The Milwau ee LGBT Film/Video Festival Final Days • Complete Guide Inside iR i t Orf LIM nI ' i FALL ARTS PREVIEW WRAP UP LOGO Star Jennie McNulty Shines Bright in Superior Plus lots more in entertainment inside! WHY BE SHY? GET TESTED for HIV, at BESTD Clinic. It's free and it's fast, with no names and no needles.We also provide free STD testing, exams, and treatment. Staffed totally by volunteers and supported by donations, BESTD has been doing HIV outreach since 1987. We're open: Mondays 6 PM-8:30 PM: Free HIV & STD testing Tuesdays 6 PM-8:30 PM: All of the above plus STD exams and treatment Some services only available for men; visit our web site for details. BESTD cum(' Brady East STD Clinic 1240 E. Brady Street Milwaukee, WI 53202 414-272-2144 www.bestd.org DIES "Legal couple status may support a relationship," LESBIAN RIGHTS PIONEER DEL MARTIN researcher Robert-Jay Green said in a statement an- Lesbian Rights Pioneer Del Mar- things. nouncing the findings. tin Dies "I also never imagined there Surprise! Log Cabin Republicans Endorse Mc- San Francisco - Just two months would be a day that we would ac- Cain-Palhi Ticket: The Log Cabin Republicans after achieving a life-long dream, tually be able to get married," Lyon (LCR), who refused to endorse George W. Bush for the legal marriage to her partner of wrote. "I am devastated, but I take reelection in 2004, announced their endorsement of 55 years, lesbian rights pioneer Del some solace in knowing we were Senator John McCain for President of the United Martin - whose trailblazing activism able to enjoy the ultimate rite of States on September 2: LCR's board of directors spanned more than a half century - love and commitment before she voted 12-2 to endorse both McCain and Alaska Gov- died August 27 at a local hospice. -

Won't Bow Don't Know

A NEW SERIES FROM THE CREATORS OF SM WON’T BOW DON’T KNOW HOW New Orleans, 2005 ONLINE GUIDE MAY 2010 SUNDAYS 10 PM/9C SATURDAYSATURDAY NIGHTSNIGHTS The prehistoric pals trade the permafrost for paradise in this third adventure in the Ice Age series. As Manny the Mammoth and his woolly wife prep for parenthood, Sid the Sloth decides to join his furry friend by fathering a trio of snatched eggs...which soon hatch into dinosaurs! It isn’t long before Mama T-Rex turns up looking for her tots and ends up leading the pack of glacial mates to a vibrant climate under the ice where dinos rule. “The best of the three films...” (Roger Ebert). Featuring the voices of Ray Romano, Screwball quantum paleontologist Will Ferrell and three companions time warp back John Leguizamo, Denis to the prehistoric age in this comical adventure based on the cult 1970s TV series. Leary, Josh Peck and Danny McBride, Anna Friel and Jorma Taccone star as Ferrell’s cohorts whose routine Queen Latifah. (MV) PG- expedition winds up leaving them in a primitive world of dinosaurs, cave-dwelling 1:34. HBO May 1,2,4,9,15, lizards, ape-like creatures and hungry mosquitoes. Directed by Brad Silberling; 19,23,27,31 C5EH written by Chris Henchy & Dennis McNicholas, based on Sid & Marty Krofft’s Land STARTS SATURDAY, of the Lost. (AC,AL,MV) PG13-1:42. HBO May 8,9,11,16,20,22,24,27,30 C5EH MAY 1 STARTS SATURDAY, MAY 8 A NEW MOVIE EVERY SATURDAY—GUARANTEED! SATURDAYSATURDAY NIGHTSNIGHTS One night in Vegas She was born to save proves to be more her sister’s life, but at than four guys arriving what cost to her own? for a bachelor party Cameron Diaz and can handle in this Abigail Breslin star in riotous Golden Globe®- this heart-pulling drama winning comedy. -

Regulating Cyber-Racism

REGULATING CYBER-RACISM GAIL M ASON* AND NATALIE CZAPSKI† Cyber-racism and other forms of cyber-bullying have become an increasing part of the internet mainstream, with 35% of Australian internet users witnessing such behaviour online. Cyber-racism poses a double challenge for effective regulation: a lack of consensus on how to define unacceptable expressions of racism; and the novel and unprecedented ways in which racism can flourish on the internet. The regulation of racism on the internet sits at the crossroads of different legal domains, but there has never been a comprehensive evaluation of these channels. This article examines the current legal and regulatory terrain around cyber-racism in Australia. This analysis exposes a gap in the capacity of current regulatory mechanisms to provide a prompt, efficient and enforceable system for responding to harmful online content of a racial nature. Drawing on recent legislative developments in tackling harmful content online, we consider the potential benefits and limitations of key elements of a civil penalties scheme to fill the gap in the present regulatory environment. We argue for a multifaceted approach, which encom- passes enforcement mechanisms to target both perpetrators and intermediaries once in- platform avenues are exhausted. Through our proposal, we can strengthen the arsenal of tools we have to deal with cyber-racism. CONTENTS I Introduction .............................................................................................................. 286 II The Double Challenge -

HBO: Brand Management and Subscriber Aggregation: 1972-2007

1 HBO: Brand Management and Subscriber Aggregation: 1972-2007 Submitted by Gareth Andrew James to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English, January 2011. This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. ........................................ 2 Abstract The thesis offers a revised institutional history of US cable network Home Box Office that expands on its under-examined identity as a monthly subscriber service from 1972 to 1994. This is used to better explain extensive discussions of HBO‟s rebranding from 1995 to 2007 around high-quality original content and experimentation with new media platforms. The first half of the thesis particularly expands on HBO‟s origins and early identity as part of publisher Time Inc. from 1972 to 1988, before examining how this affected the network‟s programming strategies as part of global conglomerate Time Warner from 1989 to 1994. Within this, evidence of ongoing processes for aggregating subscribers, or packaging multiple entertainment attractions around stable production cycles, are identified as defining HBO‟s promotion of general monthly value over rivals. Arguing that these specific exhibition and production strategies are glossed over in existing HBO scholarship as a result of an over-valuing of post-1995 examples of „quality‟ television, their ongoing importance to the network‟s contemporary management of its brand across media platforms is mapped over distinctions from rivals to 2007. -

14 European Far-Right Music and Its Enemies Anton Shekhovtsov

14 European Far-Right Music and Its Enemies Anton Shekhovtsov I’m patriotic, I’m racialistic, My views are clear and so simplistic (English Rose, 2007b) In a self-conducted interview that appeared in his manifesto, Norwegian would-be right-wing terrorist and killer Anders Behring Breivik, under the pen name Andrew Berwick, argued that specifi c music helps sustain ‘high morale and motivation’ of ‘self-fi nanced and self-indoctrinated single in- dividual attack cells’ (2011, p. 856). He went on to list several ‘motiva- tional music tracks’ he particularly liked. Breivik described one of these tracks, ‘Lux Æterna’, by Clint Mansell, which was featured in the trailer for Peter Jackson’s The Lord of the Rings : The Two Towers , as ‘very inspir- ing’ and as invoking ‘a type of passionate rage within you’ (2011, p. 858). On 22 July 2011, ‘Lux Æterna’ supposedly played in his iPod while he was killing members of the Workers’ Youth League of the Norwegian Labour Party on the island of Utøya (Gysin, Sears and Greenhill, 2011). Another artist favoured by Breivik in his manifesto is Saga, ‘a courageous, Swedish, female nationalist-oriented musician who creates pop-music with patriotic texts’ (2011, p. 856). Saga soared to the heights of right-wing fame in 2000, when she released three volumes of My Tribute to Skrewdriver on the Swedish right-wing label Midgård Records (2000a). Her three-volume album featured cover versions of Skrewdriver, a model White Power band, whose late leader, Ian Stuart Donaldson, founded the Blood & Honour (B&H) music promotion network in 1987.