Report for the Year 1872-73

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Looking at Gandhāra

HISTORIA I ŚWIAT, nr 4 (2015) ISSN 2299-2464 Kumar ABHIJEET (Magadh University, India) Looking at Gandhāra Keywords: Art History, Silk Route, Gandhāra It is not the object of the story to convey a happening per se, which is the purpose of information; rather, it embeds it in the life of the storyteller in order to pass it on as experience to those listening. It thus bears the marks of the storyteller much as the earthen vessel bears the marks of the potter's hand. —Walter Benjamin, "On Some Motifs in Baudelaire" Discovery of Ancient Gandhāra The beginning of the 19th century was revolutionary in terms of western world scholars who were eager to trace the conquest of Alexander in Asia, in speculation of the route to India he took which eventually led to the discovery of ancient Gandhāra region (today, the geographical sphere lies between North West Pakistan and Eastern Afghanistan). In 1808 CE, Mountstuart Elphinstone was the first British envoy sent in Kabul when the British went to win allies against Napoleon. He believed to identify those places, hills and vineyard described by the itinerant Greeks or the Greek Sources on Alexander's campaign in India or in their memory of which the Macedonian Commanders were connected. It is significant to note that the first time in modern scholarship the word “Thupa (Pali word for stupa)” was used by him.1 This site was related to the place where Alexander’s horse died and a city called Bucephala (Greek. Βουκεφάλα ) was erected by Alexander the Great in honor of his black horse with a peculiar shaped white mark on its forehead. -

Migration and Small Towns in Pakistan

Working Paper Series on Rural-Urban Interactions and Livelihood Strategies WORKING PAPER 15 Migration and small towns in Pakistan Arif Hasan with Mansoor Raza June 2009 ABOUT THE AUTHORS Arif Hasan is an architect/planner in private practice in Karachi, dealing with urban planning and development issues in general, and in Asia and Pakistan in particular. He has been involved with the Orangi Pilot Project (OPP) since 1982 and is a founding member of the Urban Resource Centre (URC) in Karachi, whose chairman he has been since its inception in 1989. He is currently on the board of several international journals and research organizations, including the Bangkok-based Asian Coalition for Housing Rights, and is a visiting fellow at the International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED), UK. He is also a member of the India Committee of Honour for the International Network for Traditional Building, Architecture and Urbanism. He has been a consultant and advisor to many local and foreign CBOs, national and international NGOs, and bilateral and multilateral donor agencies. He has taught at Pakistani and European universities, served on juries of international architectural and development competitions, and is the author of a number of books on development and planning in Asian cities in general and Karachi in particular. He has also received a number of awards for his work, which spans many countries. Address: Hasan & Associates, Architects and Planning Consultants, 37-D, Mohammad Ali Society, Karachi – 75350, Pakistan; e-mail: [email protected]; [email protected]. Mansoor Raza is Deputy Director Disaster Management for the Church World Service – Pakistan/Afghanistan. -

Ghfbooksouthasia.Pdf

1000 BC 500 BC AD 500 AD 1000 AD 1500 AD 2000 TAXILA Pakistan SANCHI India AJANTA CAVES India PATAN DARBAR SQUARE Nepal SIGIRIYA Sri Lanka POLONNARUWA Sri Lanka NAKO TEMPLES India JAISALMER FORT India KONARAK SUN TEMPLE India HAMPI India THATTA Pakistan UCH MONUMENT COMPLEX Pakistan AGRA FORT India SOUTH ASIA INDIA AND THE OTHER COUNTRIES OF SOUTH ASIA — PAKISTAN, SRI LANKA, BANGLADESH, NEPAL, BHUTAN —HAVE WITNESSED SOME OF THE LONGEST CONTINUOUS CIVILIZATIONS ON THE PLANET. BY THE END OF THE FOURTH CENTURY BC, THE FIRST MAJOR CONSOLIDATED CIVILIZA- TION EMERGED IN INDIA LED BY THE MAURYAN EMPIRE WHICH NEARLY ENCOMPASSED THE ENTIRE SUBCONTINENT. LATER KINGDOMS OF CHERAS, CHOLAS AND PANDYAS SAW THE RISE OF THE FIRST URBAN CENTERS. THE GUPTA KINGDOM BEGAN THE RICH DEVELOPMENT OF BUILT HERITAGE AND THE FIRST MAJOR TEMPLES INCLUDING THE SACRED STUPA AT SANCHI AND EARLY TEMPLES AT LADH KHAN. UNTIL COLONIAL TIMES, ROYAL PATRONAGE OF THE HINDU CULTURE CONSTRUCTED HUNDREDS OF MAJOR MONUMENTS INCLUDING THE IMPRESSIVE ELLORA CAVES, THE KONARAK SUN TEMPLE, AND THE MAGNIFICENT CITY AND TEMPLES OF THE GHF-SUPPORTED HAMPI WORLD HERITAGE SITE. PAKISTAN SHARES IN THE RICH HISTORY OF THE REGION WITH A WEALTH OF CULTURAL DEVELOPMENT AROUND ISLAM, INCLUDING ADVANCED MOSQUE ARCHITECTURE. GHF’S CONSER- VATION OF ASIF KHAN TOMB OF THE JAHANGIR COMPLEX IN LAHORE, PAKISTAN WILL HELP PRESERVE A STUNNING EXAMPLE OF THE GLORIOUS MOGHUL CIVILIZATION WHICH WAS ONCE CENTERED THERE. IN THE MORE REMOTE AREAS OF THE REGION, BHUTAN, SRI LANKA AND NEPAL EACH DEVELOPED A UNIQUE MONUMENTAL FORM OF WORSHIP FOR HINDUISM. THE MOST CHALLENGING ASPECT OF CONSERVATION IS THE PLETHORA OF HERITAGE SITES AND THE LACK OF RESOURCES TO COVER THE COSTS OF CONSERVATION. -

Geography of Early Historical Punjab

Geography of Early Historical Punjab Ardhendu Ray Chatra Ramai Pandit Mahavidyalaya Chatra, Bankura, West Bengal The present paper is an attempt to study the historical geography of Punjab. It surveys previous research, assesses the emerging new directions in historical geography of Punjab, and attempts to understand how archaeological data provides new insights in this field. Trade routes, urbanization, and interactions in early Punjab through material culture are accounted for as significant factors in the overall development of historical and geographical processes. Introduction It has aptly been remarked that for an intelligent study of the history of a country, a thorough knowledge of its geography is crucial. Richard Hakluyt exclaimed long ago that “geography and chronology are the sun and moon, the right eye and left eye of all history.”1 The evolution of Indian history and culture cannot be rightly understood without a proper appreciation of the geographical factors involved. Ancient Indian historical geography begins with the writings of topographical identifications of sites mentioned in the literature and inscriptions. These were works on geographical issues starting from first quarter of the nineteenth century. In order to get a clear understanding of the subject matter, now we are studying them in different categories of historical geography based on text, inscriptions etc., and also regional geography, cultural geography and so on. Historical Background The region is enclosed between the Himalayas in the north and the Rajputana desert in the south, and its rich alluvial plain is composed of silt deposited by the 2 JSPS 24:1&2 rivers Sutlej, Beas, Ravi, Chenab and Jhelum. -

Widening / Improvement of Main Road Leading to Uch Sharif District Bahawalpur

ENVIRONMENT AND SOCIAL MANAGEMENT PLAN (ESMP) Widening / Improvement of main road leading to Uch Sharif District Bahawalpur (December, 2020) Environment and Social Management Plan (ESMP) Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................... 3 CHAPTER-01 INTRODUCTION .............................................................................. 7 1.1 Project Description ..................................................................... 7 1.2 Environmental and Social Management Framework (ESMF). 78 1.2.1 Environmental and Social Management Plan (ESMP) ................ 78 1.2.2 Objectives of Environmental and Social Management Plan (ESMP) ................................................................................................... 78 1.3 Scope of Environmental and Social Management Plan ......... 89 1.4 ESMP Methodology .................................................................. 89 I. Literature Review ........................................................................ 89 II. Review of Legal and Policy Frameworks Requirements ............. 89 III. Baseline Data Collection- Environmental and Social Surveys ..... 89 IV. Identification and Assessment of Environmental and Social Impacts Mitigation Measures ........................................................ 9 V. Environmental and Social Impacts Mitigation and Monitoring Plan ................................................................................................. 910 VI. Institutional -

Contesting Candidates NA-1 Peshawar-I

Form-V: List of Contesting Candidates NA-1 Peshawar-I Serial No Name of contestng candidate in Address of contesting candidate Symbol Urdu Alphbeticl order Allotted 1 Sahibzada PO Ashrafia Colony, Mohala Afghan Cow Colony, Peshawar Akram Khan 2 H # 3/2, Mohala Raza Shah Shaheed Road, Lantern Bilour House, Peshawar Alhaj Ghulam Ahmad Bilour 3 Shangar PO Bara, Tehsil Bara, Khyber Agency, Kite Presented at Moh. Gul Abad, Bazid Khel, PO Bashir Ahmad Afridi Badh Ber, Distt Peshawar 4 Shaheen Muslim Town, Peshawar Suitcase Pir Abdur Rehman 5 Karim Pura, H # 282-B/20, St 2, Sheikhabad 2, Chiragh Peshawar (Lamp) Jan Alam Khan Paracha 6 H # 1960, Mohala Usman Street Warsak Road, Book Peshawar Haji Shah Nawaz 7 Fazal Haq Baba Yakatoot, PO Chowk Yadgar, H Ladder !"#$%&'() # 1413, Peshawar Hazrat Muhammad alias Babo Maavia 8 Outside Lahore Gate PO Karim Pura, Peshawar BUS *!+,.-/01!234 Khalid Tanveer Rohela Advocate 9 Inside Yakatoot, PO Chowk Yadgar, H # 1371, Key 5 67'8 Peshawar Syed Muhammad Sibtain Taj Agha 10 H # 070, Mohala Afghan Colony, Peshawar Scale 9 Shabir Ahmad Khan 11 Chamkani, Gulbahar Colony 2, Peshawar Umbrella :;< Tariq Saeed 12 Rehman Housing Society, Warsak Road, Fist 8= Kababiyan, Peshawar Amir Syed Monday, April 22, 2013 6:00:18 PM Contesting candidates Page 1 of 176 13 Outside Lahori Gate, Gulbahar Road, H # 245, Tap >?@A= Mohala Sheikh Abad 1, Peshawar Aamir Shehzad Hashmi 14 2 Zaman Park Zaman, Lahore Bat B Imran Khan 15 Shadman Colony # 3, Panal House, PO Warsad Tiger CDE' Road, Peshawar Muhammad Afzal Khan Panyala 16 House # 70/B, Street 2,Gulbahar#1,PO Arrow FGH!I' Gulbahar, Peshawar Muhammad Zulfiqar Afghani 17 Inside Asiya Gate, Moh. -

Phase Iii Architecture and Sculpture from Taxila 6.1

CHAPTER SIX PHASE III ARCHITECTURE AND SCULPTURE FROM TAXILA 6.1 Introduction to the Phase III Developments in the Sacred Areas and Afonasteries ef Taxila and the Peshawar Basin A dramatic increase in patronage occurred across the Peshawar basin, Taxila, and Swat during phase III; most of the extant remains in these regions were constructed at this time. As devotional icons of Buddhas and bodhisattvas became increasingly popular, parallel trans formations occurred in the sacred areas, which still remained focused around relic stupas. In the Peshawar basin, Taxila, and to a lesser degree Swat, the widespread incorporation of large iconic images clearly reflects changes occurring in Buddhist practice. Although it is difficult to know how the sacred precincts were ritually used, modifications in the spatial organization of both sacred areas and monasteries provide some insight. Not surprisingly, the use and incorporation of devotional images developed regionally. The most dramatic shift toward icons is observed in the Peshawar basin and some of the Taxila sites. In contrast, Swat seemed to follow a different pattern, as fewer image shrines were fabricated and sacred areas were organized along different lines. This might reflect a lack of patronage; perhaps new sites following the Peshawar basin format were not commissioned because of a lack of resources. More likely, the Buddhist tradition in Swat was of a different character; some sites-notably Butkara I-show significant expansion following a uniquely Swati format. At a few sites in Swat, however, image shrines appear in positions analogous to those of the Peshawar basin; Nimogram and Saidu (figs. 109, 104) arc notable examples. -

The Stūpa of Bharhut

CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY GIFT OF Alexander B. Griswold FINE ARTS Cornell Univ.;rsily Library NA6008.B5C97 The stupa of Bharhut:a Buddhist monumen 3 1924 016 181 111 ivA Cornell University Library Al The original of this bool< is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31 92401 6181111 ; THE STUPA OF BHARHUT: A BUDDHIST MONUMENT ORNAMENTED WITH NUMEROUS SCULPTURES ILLUSTRATIVE OF BTJDDHIST LEGEND AND HISTOEY IN THE THIRD CENTURY B.C. BY ALEXANDER CUNNINGHAM, C.S.I., CLE., ' ' ' ^ MAJOE GENERAL, EOYAL ENGINEERS (BENGAL, RETIRED). DIRECTOR GENERAL ARCHffiOLOGICAL SURVEY OF INDIA. " In the sculptures ancL insorvptions of Bharliut we shall have in future a real landmarh in the religious and literary history of India, and many theories hitherto held hy Sanskrit scholars will have to he modified accordingly."— Dr. Max Mullee. UlM(h hu Mw af i\( Mx(hx^ tii ^tate Ux %nVm in €mml LONDON: W^ H. ALLEN AND CO., 13, WATERLOO PLACE, S.W. TRUBNER AND CO., 57 & 59, LUDGATE HILL; EDWARD STANFORD, CHARING CROSS; W. S. WHITTINGHAM AND CO., 91, GRACECHURCH STREET; THACKER AND CO., 87, NEWGATE STREET. 1879. CONTENTS. page E.—SCULPTURED SCENES. PAGE PREFACE V 1. Jata^as, oe pebvious Bieths of Buddha - 48 2. HisTOEicAL Scenes - - - 82 3. Miscellaneous Scenes, insceibed - 93 I.—DESCRIPTION OF STUPA. 4. Miscellaneous Scenes, not insceibed - 98 1. Position of Bhakhut 1 5. HuMOEOUS Scenes - - - 104 2. Desckipiion of Stupa 4 F.— OF WORSHIP 3. Peobable Age of Stupa - 14 OBJECTS 1. -

Forestry in the Princely State of Swat and Kalam (North-West Pakistan)

Forestry in the Princely State of Swat and Kalam (North-West Pakistan) A Historical Perspective on Norms and Practices IP6 Working Paper No.6 Sultan-i-Rome, Ph.D. 2005 Forestry in the Princely State of Swat and Kalam (North-West Pakistan) A Historical Perspective on Norms and Practices IP6 Working Paper No.6 Sultan-i-Rome, Ph.D. 2005 The Swiss National Centre of Competence in Research (NCCR) North-South is based on a network of partnerships with research institutions in the South and East, focusing on the analysis and mitigation of syndromes of global change and globalisation. Its sub-group named IP6 focuses on institutional change and livelihood strategies: State policies as well as other regional and international institutions – which are exposed to and embedded in national economies and processes of globalisation and global change – have an impact on local people's livelihood practices and strategies as well as on institutions developed by the people themselves. On the other hand, these institutionally shaped livelihood activities have an impact on livelihood outcomes and the sustainability of resource use. Understanding how the micro- and macro-levels of this institutional context interact is of vital importance for developing sustainable local natural resource management as well as supporting local livelihoods. For an update of IP6 activities see http://www.nccr-north-south.unibe.ch (>Individual Projects > IP6) The IP6 Working Paper Series presents preliminary research emerging from IP6 for discussion and critical comment. Author Sultan-i-Rome, Ph.D. Village & Post Office Hazara, Tahsil Kabal, Swat–19201, Pakistan e-mail: [email protected] Distribution A Downloadable pdf version is availale at www.nccr- north-south.unibe.ch (-> publications) Cover Photo The Swat Valley with Mingawara, and Upper Swat in the background (photo Urs Geiser) All rights reserved with the author. -

Archaeological Survey of District Mardan in the North-West Frontier Province of Pakistan

55 Ancient Pakistan, Vol. XIV Archaeological Survey of District Mardan in the North-West Frontier Province of Pakistan TAJ ALI Contents Introduction 56 Aims and Objectives of the Survey 56 Geography and Land Economy 57 Historical and Archaeological Perspective 58 Early Surveys, Explorations and Excavations 60 List of Protected Sites and Monuments 61 Inventory of Archaeological Sites Recorded in the Current Survey 62 Analysis of Archaeological Data from the Surface Collection 98 Small Finds 121 Conclusion 126 Sites Recommended for Excavation, Conservation and Protection 128 List of Historic I Settlement Sites 130 Acknowledgements 134 Notes 134 Bibliographic References 135 Map 136 Figures 137 Plates 160 56 Ancient Pakistan, Vol. XIV Archaeological Survey of District Mardan in the North-West Frontier Province of Pakistan TAJ ALI Introduction The Department of Archaeology, University of Peshawar, (hereafter the Department) in collaboration with the Department of Archaeology and Museums, Government of Pakistan, (hereafter the Federal Department) initiated a project of surveying and documenting archaeological sites and historical monuments in the North-West Frontier Province (NWFP). The primary objectives of the project were to formulate plans for future research, highlight and project the cultural heritage of the Province and to promote cultural tourism for sustainable development. The Department started the project in 1993 and since then has published two survey reports of the Charsadda and Swabi Districts. 1 Dr. Abdur Rahman conducted survey of the Peshawar and Nowshera Districts and he will publish the report after analysis of the data. 2 Conducted by the present author, the current report is focussed on the archaeological survey of the Mardan District, also referred to as the Yusafzai Plain or District. -

The Ancient Geography of India

िव�ा �सारक मंडळ, ठाणे Title : Ancient Geography of India : I : The Buddhist Period Author : Cunningham, Alexander Publisher : London : Trubner and Co. Publication Year : 1871 Pages : 628 गणपुस्त �व�ा �सारत मंडळाच्ा “�ंथाल्” �तल्पा्गर् िनिमर्त गणपुस्क िन�म्ी वषर : 2014 गणपुस्क �मांक : 051 CHARLES WILLIAM WASON COLLECTION CHINA AND THE CHINESE THE GIFT OF CHARLES WILLIAM WASON CLASS OF 1876 1918 Cornell University Library DS 409.C97 The ancient geqgraphv.of India 3 1924 023 029 485 f mm Cornell University Library The original of tliis book is in tine Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924023029485 THE ANCIENT GEOGRAPHY ov INDIA. A ".'i.inMngVwLn-j inl^ : — THE ANCIENT GEOGRAPHY INDIA. THE BUDDHIST PERIOD, INCLUDING THE CAMPAIGNS OP ALEXANDER, AND THE TRAVELS OF HWEN-THSANG. ALEXANDER CUNNINGHAM, Ui.JOB-GBirBBALj BOYAL ENGINEEBS (BENGAL BETIBBD). " Venun et terrena demoDstratio intelligatar, Alezandri Magni vestigiiB insistamns." PHnii Hist. Nat. vi. 17. WITS TSIRTBBN MAPS. LONDON TEUBNER AND CO., 60, PATERNOSTER ROW. 1871. [All Sights reserved.'] {% A\^^ TATLOB AND CO., PEIKTEES, LITTLE QUEEN STKEET, LINCOLN'S INN EIELDS. MAJOR-Q-ENEEAL SIR H. C. RAWLINSON, K.G.B. ETC. ETC., WHO HAS HIMSELF DONE SO MUCH ^ TO THROW LIGHT ON THE ANCIENT GEOGRAPHY OP ASIA, THIS ATTEMPT TO ELUCIDATE A PARTIODLAR PORTION OF THE SUBJKcr IS DEDICATED BY HIS FRIEND, THE AUTHOR. PEEFACE. The Geography of India may be conveniently divided into a few distinct sections, each broadly named after the prevailing religious and political character of the period which it embraces, as the Brahnanical, the Buddhist^ and the Muhammadan. -

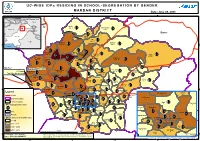

UC-WISE Idps RESIDING in SCHOOL-SEGREGATION BY

FANA U C - W I S E I D P s R E S I D I N G I N S C H O O L - S E G R E G AT I O N B Y G E N D E R UNOCHA M A R D A N D I S T R I C T Date :June 08, 2009 71°50'E 72°E 72°10'E 72°20'E Kazakhstan Kyrgyzstan Uzbekistan IDPs Intervention Area Tajikistan China Turkmenistan Pakistan Aksai Chin Kharki Jammu Kashmir ´ 406 ,6 Kohi Bermol Afghanistan 114 ,5 MalakCahina/dInd iPa A Buner PAKISTAN Qasmi Nepal 680 ,14 Iran Alo India 964 ,20 N N " Mian Issa Babozai " 0 0 3 3 ' ' 5 1638 ,40 222 ,8 5 2 2 ° ° 4 4 3 Arabian Sea 3 Shergarh Makori 959 ,19 Dherai Likpani 1028 ,16 Shamozai Bazar 1553 ,41 848 ,20 Lund Khawar 663 ,13 Hathian Pir Saddo 2911 ,41 Katlang-1 Palo Dheri 1631 ,21 Jalala 2760 ,18 Kati Garhi 928 ,15 1020 ,18 1741 ,16 572 ,15 Rustam 489 ,8 Katlang-2 Map Key: Takht Bhai 486 ,17 Mardan Kata Khat Parkho Dherai Jamal Garhi Chargalli UC Name Madey Baba 368 ,14 1927 ,35 183 ,6 383 ,11 1520 ,27 Sawal Dher Total IDPs, No of School 546 ,13 Daman-e-Koh Takkar 1317 ,5 1407 ,11 Kot Jungarah Mardan 2003 ,21 Machi Fathma Bakhshali Gujrat 91 ,4 Pat Baba 716 ,15 449 ,9 469 ,6 Narai 803 ,11 Garyala 948 ,21 Bala Garhi 711 ,15 Seri Bahlol 447 ,14 N N ' 1194 ,20 ' 5 Babini 5 1 Jehangir Abad 1 ° ° 4 Saro Shah 4 3 1092 ,11 725 ,10 Shahbaz Garhi 3 1139 ,16 Legend 340 ,12 Gujar Garhi Jehangir Abad Babini 1237 ,9 Mohib Banda 11 10 Roads Charsadda BaghdadaDagai Chak Hoti Baghicha Dheri 1451 ,11 707 ,16 528 ,8 156 ,4 212 ,5 Garhi Daulatzai Gujar Garhi District Boundary Mardan Rural 9 252 ,6 493 ,6 Chamtar Tehsil Boundary Dagai 267 ,8 Par Hoti Chak Hoti Khazana Dheri