Phase Iii Architecture and Sculpture from Taxila 6.1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Looking at Gandhāra

HISTORIA I ŚWIAT, nr 4 (2015) ISSN 2299-2464 Kumar ABHIJEET (Magadh University, India) Looking at Gandhāra Keywords: Art History, Silk Route, Gandhāra It is not the object of the story to convey a happening per se, which is the purpose of information; rather, it embeds it in the life of the storyteller in order to pass it on as experience to those listening. It thus bears the marks of the storyteller much as the earthen vessel bears the marks of the potter's hand. —Walter Benjamin, "On Some Motifs in Baudelaire" Discovery of Ancient Gandhāra The beginning of the 19th century was revolutionary in terms of western world scholars who were eager to trace the conquest of Alexander in Asia, in speculation of the route to India he took which eventually led to the discovery of ancient Gandhāra region (today, the geographical sphere lies between North West Pakistan and Eastern Afghanistan). In 1808 CE, Mountstuart Elphinstone was the first British envoy sent in Kabul when the British went to win allies against Napoleon. He believed to identify those places, hills and vineyard described by the itinerant Greeks or the Greek Sources on Alexander's campaign in India or in their memory of which the Macedonian Commanders were connected. It is significant to note that the first time in modern scholarship the word “Thupa (Pali word for stupa)” was used by him.1 This site was related to the place where Alexander’s horse died and a city called Bucephala (Greek. Βουκεφάλα ) was erected by Alexander the Great in honor of his black horse with a peculiar shaped white mark on its forehead. -

Buddhist Histories

JIABS Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies Volume 25 Number 1-2 2002 Buddhist Histories Richard SALOMON and Gregory SCHOPEN On an Alleged Reference to Amitabha in a KharoÒ†hi Inscription on a Gandharian Relief .................................................................... 3 Jinhua CHEN Sarira and Scepter. Empress Wu’s Political Use of Buddhist Relics 33 Justin T. MCDANIEL Transformative History. Nihon Ryoiki and Jinakalamalipakara∞am 151 Joseph WALSER Nagarjuna and the Ratnavali. New Ways to Date an Old Philosopher................................................................................ 209 Cristina A. SCHERRER-SCHAUB Enacting Words. A Diplomatic Analysis of the Imperial Decrees (bkas bcad) and their Application in the sGra sbyor bam po gnis pa Tradition....................................................................................... 263 Notes on the Contributors................................................................. 341 ON AN ALLEGED REFERENCE TO AMITABHA IN A KHARO∑™HI INSCRIPTION ON A GANDHARAN RELIEF RICHARD SALOMON AND GREGORY SCHOPEN 1. Background: Previous study and publication of the inscription This article concerns an inscription in KharoÒ†hi script and Gandhari language on the pedestal of a Gandharan relief sculpture which has been interpreted as referring to Amitabha and Avalokitesvara, and thus as hav- ing an important bearing on the issue of the origins of the Mahayana. The sculpture in question (fig. 1) has had a rather complicated history. According to Brough (1982: 65), it was first seen in Taxila in August 1961 by Professor Charles Kieffer, from whom Brough obtained the photograph on which his edition of the inscription was based. Brough reported that “[o]n his [Kieffer’s] return to Taxila a month later, the sculpture had dis- appeared, and no information about its whereabouts was forthcoming.” Later on, however, it resurfaced as part of the collection of Dr. -

The Image of the Winged Celestial and Its Travels Along the Silk Road

SINO-PLATONIC PAPERS Number 225 June, 2012 The Image of the Winged Celestial and Its Travels along the Silk Road by Patricia Eichenbaum Karetzky Victor H. Mair, Editor Sino-Platonic Papers Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations University of Pennsylvania Philadelphia, PA 19104-6305 USA [email protected] www.sino-platonic.org SINO-PLATONIC PAPERS FOUNDED 1986 Editor-in-Chief VICTOR H. MAIR Associate Editors PAULA ROBERTS MARK SWOFFORD ISSN 2157-9679 (print) 2157-9687 (online) SINO-PLATONIC PAPERS is an occasional series dedicated to making available to specialists and the interested public the results of research that, because of its unconventional or controversial nature, might otherwise go unpublished. The editor-in-chief actively encourages younger, not yet well established, scholars and independent authors to submit manuscripts for consideration. Contributions in any of the major scholarly languages of the world, including romanized modern standard Mandarin (MSM) and Japanese, are acceptable. In special circumstances, papers written in one of the Sinitic topolects (fangyan) may be considered for publication. Although the chief focus of Sino-Platonic Papers is on the intercultural relations of China with other peoples, challenging and creative studies on a wide variety of philological subjects will be entertained. This series is not the place for safe, sober, and stodgy presentations. Sino- Platonic Papers prefers lively work that, while taking reasonable risks to advance the field, capitalizes on brilliant new insights into the development of civilization. Submissions are regularly sent out to be refereed, and extensive editorial suggestions for revision may be offered. Sino-Platonic Papers emphasizes substance over form. -

The Parinirvana Cycle and the Theory of Multivalence: a Study Of

THE PARINIRVĀṆA CYCLE AND THE THEORY OF MULTIVALENCE: A STUDY OF GANDHĀRAN BUDDHIST NARRATIVE RELIEFS A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI’I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENT FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN ART HISTORY MAY 2017 By Emily Hebert Thesis Committee: Paul Lavy, Chairperson Kate Lingley Jesse Knutson TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES ....................................................................................................................... ii INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................................... 1 CHAPTER 1. BUDDHISM IN GREATER GANDHĀRA ........................................................... 9 Geography of Buddhism in Greater Gandhāra ....................................................................... 10 Buddhist Textual Traditions in Greater Gandhāra .................................................................. 12 Historical Periods of Buddhism in Greater Gandhāra ........................................................... 19 CHAPTER 2. GANDHĀRAN STŪPAS AND NARRATIVE ART ............................................. 28 Gandhāran Stūpas and Narrative Art: Architectural Context ................................................. 35 CHAPTER 3. THE PARINIRVĀṆA CYLCE OF NARRATIVE RELIEFS ................................ 39 CHAPTER 4 .THE THEORY OF MULTIVALENCE AND THE PARINIRVĀṆA CYCLE ...... 44 CHAPTER 5. NARRATIVE RELIEF PANELS FROM THE PARINIRVĀṆA CYCLE ............ 58 Episode -

Archaeological Survey of District Mardan in the North-West Frontier Province of Pakistan

55 Ancient Pakistan, Vol. XIV Archaeological Survey of District Mardan in the North-West Frontier Province of Pakistan TAJ ALI Contents Introduction 56 Aims and Objectives of the Survey 56 Geography and Land Economy 57 Historical and Archaeological Perspective 58 Early Surveys, Explorations and Excavations 60 List of Protected Sites and Monuments 61 Inventory of Archaeological Sites Recorded in the Current Survey 62 Analysis of Archaeological Data from the Surface Collection 98 Small Finds 121 Conclusion 126 Sites Recommended for Excavation, Conservation and Protection 128 List of Historic I Settlement Sites 130 Acknowledgements 134 Notes 134 Bibliographic References 135 Map 136 Figures 137 Plates 160 56 Ancient Pakistan, Vol. XIV Archaeological Survey of District Mardan in the North-West Frontier Province of Pakistan TAJ ALI Introduction The Department of Archaeology, University of Peshawar, (hereafter the Department) in collaboration with the Department of Archaeology and Museums, Government of Pakistan, (hereafter the Federal Department) initiated a project of surveying and documenting archaeological sites and historical monuments in the North-West Frontier Province (NWFP). The primary objectives of the project were to formulate plans for future research, highlight and project the cultural heritage of the Province and to promote cultural tourism for sustainable development. The Department started the project in 1993 and since then has published two survey reports of the Charsadda and Swabi Districts. 1 Dr. Abdur Rahman conducted survey of the Peshawar and Nowshera Districts and he will publish the report after analysis of the data. 2 Conducted by the present author, the current report is focussed on the archaeological survey of the Mardan District, also referred to as the Yusafzai Plain or District. -

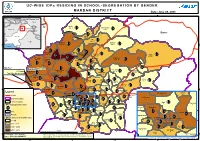

UC-WISE Idps RESIDING in SCHOOL-SEGREGATION BY

FANA U C - W I S E I D P s R E S I D I N G I N S C H O O L - S E G R E G AT I O N B Y G E N D E R UNOCHA M A R D A N D I S T R I C T Date :June 08, 2009 71°50'E 72°E 72°10'E 72°20'E Kazakhstan Kyrgyzstan Uzbekistan IDPs Intervention Area Tajikistan China Turkmenistan Pakistan Aksai Chin Kharki Jammu Kashmir ´ 406 ,6 Kohi Bermol Afghanistan 114 ,5 MalakCahina/dInd iPa A Buner PAKISTAN Qasmi Nepal 680 ,14 Iran Alo India 964 ,20 N N " Mian Issa Babozai " 0 0 3 3 ' ' 5 1638 ,40 222 ,8 5 2 2 ° ° 4 4 3 Arabian Sea 3 Shergarh Makori 959 ,19 Dherai Likpani 1028 ,16 Shamozai Bazar 1553 ,41 848 ,20 Lund Khawar 663 ,13 Hathian Pir Saddo 2911 ,41 Katlang-1 Palo Dheri 1631 ,21 Jalala 2760 ,18 Kati Garhi 928 ,15 1020 ,18 1741 ,16 572 ,15 Rustam 489 ,8 Katlang-2 Map Key: Takht Bhai 486 ,17 Mardan Kata Khat Parkho Dherai Jamal Garhi Chargalli UC Name Madey Baba 368 ,14 1927 ,35 183 ,6 383 ,11 1520 ,27 Sawal Dher Total IDPs, No of School 546 ,13 Daman-e-Koh Takkar 1317 ,5 1407 ,11 Kot Jungarah Mardan 2003 ,21 Machi Fathma Bakhshali Gujrat 91 ,4 Pat Baba 716 ,15 449 ,9 469 ,6 Narai 803 ,11 Garyala 948 ,21 Bala Garhi 711 ,15 Seri Bahlol 447 ,14 N N ' 1194 ,20 ' 5 Babini 5 1 Jehangir Abad 1 ° ° 4 Saro Shah 4 3 1092 ,11 725 ,10 Shahbaz Garhi 3 1139 ,16 Legend 340 ,12 Gujar Garhi Jehangir Abad Babini 1237 ,9 Mohib Banda 11 10 Roads Charsadda BaghdadaDagai Chak Hoti Baghicha Dheri 1451 ,11 707 ,16 528 ,8 156 ,4 212 ,5 Garhi Daulatzai Gujar Garhi District Boundary Mardan Rural 9 252 ,6 493 ,6 Chamtar Tehsil Boundary Dagai 267 ,8 Par Hoti Chak Hoti Khazana Dheri -

KHYBER PAKHTUNKHWA PROVINCE and NORTHERN AREAS PROTECTED by the FEERAL GOVERNMENT Abbottabad District 1

ARCHAEOLOGICAL SITES AND MONUMENTS IN KHYBER PAKHTUNKHWA PROVINCE AND NORTHERN AREAS PROTECTED BY THE FEERAL GOVERNMENT Abbottabad District 1. Jandial, A,B,C,D, (excavated remains), Tafikian, Abbottabad. 2. Sirsukh city, Marchabad, Abbottabad. 3. Jaulian site, Jaulian, Abbottabad. 4. Piplan site, Jaulian, Abbottabad. 5. Garhian (Lal Chak) stupa and monastery, Garhian, Abbottabad. 6. Badalpur stupa and monastery, Badalpur, Abbottabad. 7. Ancient stie, Bhamala, Abbottabad. 8. Tofikian mound, Tofikian, Abbottabad. 9. Therr Bajran Sites B,C,D, Tofikian, Abbottabad. 10. Pind Ghakhran mound, Pind Ghakhran, Abbottabad. 11. Mirpur mound, Mirpur, Abbottabad. 12. Tope iste (mound), Jaulian, Abbottabad. 13. Bhera (mound) Bhera, Abbottabad. 14. Chitti site, Chitti, Abbottabad. 15. Tarnawa Chitti site A & B, Tarawa, Abbottabad. 16. Burj or Tuma site, Garamthun, Abbottabad. 17. Bhari Dheri, Kutehra, Abbottabad. 18. Dana Wali, Kutehra, Abbottabad. 19. Tope site, Kamalpur, Abbottabad. 20. Part of site, Dobandi, Abbottabad. 21. Zuro Dheri, Village Shin kiari, Abbottabad. Bannu District 22. Akra (A) mound, near Village Bhart, Bannu. 23. Akra (B) mound, near Village, Vhart, Bannu. 24. Sheri Khan Tarakai, Village Jani Khel Wazir, Bannu. 25. Ghundai, Village Bakka, Khel Wazir, Bannu. Buner District 26. Ranighat Totalai, Buner. Dera Ismail Khan District 27. Northern Kafir Kot, ancient fort and temple, Umer Khel, D.I.Khan. 28. Graveryard including four tombs at Lal Mohra Sharif, Lunda Pahar, D.I.Khan 29. Rehman Dheri, Hisam, D.I.Khan. 31. Southern Kafir Kot, ancient fort and temple, Bilot, D.I.Khan. Kohat District 32. Kohat fort, Kohat. Mansehra District 33. Tomb of Hazrat Shaheed Ahmad Maujadid Baralvi, Bala Kot, Mansehra. 34. Tomb of Shah Ismail Shaheed, Bala Kot, Mansehra. -

1 Annexure - D Names of Village / Neighbourhood Councils Alongwith Seats Detail of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa

1 Annexure - D Names of Village / Neighbourhood Councils alongwith seats detail of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa No. of General Seats in No. of Seats in VC/NC (Categories) Names of S. Names of Tehsil Councils No falling in each Neighbourhood Village N/Hood Total Col Peasants/Work S. No. Village Councils (VC) S. No. Women Youth Minority . district Council Councils (NC) Councils Councils 7+8 ers 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Abbottabad District Council 1 1 Dalola-I 1 Malik Pura Urban-I 7 7 14 4 2 2 2 2 Dalola-II 2 Malik Pura Urban-II 7 7 14 4 2 2 2 3 Dabban-I 3 Malik Pura Urban-III 5 8 13 4 2 2 2 4 Dabban-II 4 Central Urban-I 7 7 14 4 2 2 2 5 Boi-I 5 Central Urban-II 7 7 14 4 2 2 2 6 Boi-II 6 Central Urban-III 7 7 14 4 2 2 2 7 Sambli Dheri 7 Khola Kehal 7 7 14 4 2 2 2 8 Bandi Pahar 8 Upper Kehal 5 7 12 4 2 2 2 9 Upper Kukmang 9 Kehal 5 8 13 4 2 2 2 10 Central Kukmang 10 Nawa Sher Urban 5 10 15 4 2 2 2 11 Kukmang 11 Nawansher Dhodial 6 10 16 4 2 2 2 12 Pattan Khurd 5 5 2 1 1 1 13 Nambal-I 5 5 2 1 1 1 14 Nambal-II 6 6 2 1 1 1 Abbottabad 15 Majuhan-I 7 7 2 1 1 1 16 Majuhan-II 6 6 2 1 1 1 17 Pattan Kalan-I 5 5 2 1 1 1 18 Pattan Kalan-II 6 6 2 1 1 1 19 Pattan Kalan-III 6 6 2 1 1 1 20 Sialkot 6 6 2 1 1 1 21 Bandi Chamiali 6 6 2 1 1 1 22 Bakot-I 7 7 2 1 1 1 23 Bakot-II 6 6 2 1 1 1 24 Bakot-III 6 6 2 1 1 1 25 Moolia-I 6 6 2 1 1 1 26 Moolia-II 6 6 2 1 1 1 1 Abbottabad No. -

The Geography of Gandhāran Art

The Geography of Gandhāran Art Proceedings of the Second International Workshop of the Gandhāra Connections Project, University of Oxford, 22nd-23rd March, 2018 Edited by Wannaporn Rienjang Peter Stewart Archaeopress Archaeology Archaeopress Publishing Ltd Summertown Pavilion 18-24 Middle Way Summertown Oxford OX2 7LG www.archaeopress.com ISBN 978-1-78969-186-3 ISBN 978-1-78969-187-0 (e-Pdf) DOI: 10.32028/9781789691863 © Archaeopress and the individual authors 2019 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright owners. This book is available direct from Archaeopress or from our website www.archaeopress.com Contents Acknowledgements ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������iii Editors’ note �����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������iii Contributors ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� iv Preface ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� ix Wannaporn Rienjang and Peter Stewart Part 1 Artistic Geographies Gandhāran art(s): methodologies and preliminary results of a stylistic analysis ������������������������� 3 Jessie Pons -

Pakistan Archaeology

Pakistan Archaeology Number 32-2017 DEPARTMENT OF ARCHAEOLOGY AND MUSEUMS GOVERNMENT OF PAKISTAN ISLAMABAD i Pakistan Archaeology Number 32-2017 ii Pakistan Archaeology Number 32-2017 Chief Editor Abdul Azeem Editor Mahmood-ul-Hasan DEPARTMENT OF ARCHAEOLOGY AND MUSEUMS GOVERNMENT OF PAKISTAN ISLAMABAD iii BOARD OF EDITORS Dr. Abdul Azeem Dr. Aurore DIDIER Director, Director, Department of Archaeology and French Archaeological Mission in Museums, Government of Pakistan, the Indus Basin Islamabad CNRS-UMR 7041/ArScAn 21, allee de l’Universite 92023 Nanterre Cedex-France Mahmood-ul-Hasan Dr. Chongfeng Li Assistant Director, Professor of Buddhist Art and Department of Archaeology and Archaeology, Museums, Government of Pakistan, Peking University, Islamabad School of Archaeology and Museology, Beijing, China Prof. Dr. Muhammad Ashraf Dr. Luca M. Olivieri Khan Director, Former Director, Taxila Institute of Italian Archaeological Mission in Asian Civilizations, Quaid-i-Azam Pakistan University, Plazzo Baleani, Islamabad, Pakistan Corso Vittorio Emanuele, Rome, Italy Mr. Saleem-ul-Haq Dr. Pia Brancaccio Former Director, Associate Professor, Department of Archaeology and Department of Art and Art History, Museums, Government of Punjab, Drexel University, Lahore, Pakistan Westphal College of Media Arts and Design, Philadelphia, USA iv © Department of Archaeology and Museums, Pakistan 2017 ISSN 0078-7868 Price in Pakistan: Rs. 1000.00 Foreign Price U. S. $ 40 Published by The Department of Archaeology and Museums Government of Pakistan, Islamabad Printed by Graphics Point Pak Media Foundation Building, G-8 Mrkaz, Islamabad, Pakistan v CONTENTS Illustrations……………………………………………….. vii Editorial…………………………………………………... xii Explorations Discovery of Rock art in Azad Jammu and Kashmir 15 M. Ashraf Khan and Sundus Aslam Khan and Saqib Raza…….. -

Buddha Stone Images in Sub-Regional Office, Peshawar: Classification and Stylistic Analysis

BUDDHA STONE IMAGES IN SUB-REGIONAL OFFICE, PESHAWAR: CLASSIFICATION AND STYLISTIC ANALYSIS By Tahir Saeed TAXILA INSTITUTE OF ASIAN CIVILIZATIONS QUAID-I-AZAM UNIVERSITY, ISLAMABAD, PAKISTAN 2017 Author’s Declaration I, Tahir Saeed hereby state that my PhD thesis titles “Buddha Stone Images in Sub-Regional Office, Peshawar: Classification and Stylistic Analysis” is my own work and not been submitted previously by me for taking any degree from Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad or anywhere else in the country/world. At any time if my statement is found to be incorrect even after my Graduate the university has the right to withdraw my PhD degree. Name of student: Tahir Saeed Dated: 13-08-2018. i Plagiarism Undertaking I solemnly declare that research work presented in the thesis titled “Buddha Stone Images in Sub- Regional Office, Peshawar: Classification and Stylistic Analysis” is solely my research work with no significant contribution from any person. Small contribution / help wherever taken has been duly acknowledged and that complete thesis has been written by me. I understand the Zero tolerance policy of the HEC and Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad towards plagiarism. Therefore, I as an author of the above titled thesis declare that no portion of my thesis has been plagiarized and my material used as reference is properly referred/ cited. I undertake that if I am found guilty of any formal plagiarism in the above titled thesis even after award of PhD degree, the University reserves the right to with draw/revoke my PhD degree and that HEC and the University has the right to publish may name of the HEC/University Website on which names of students are placed who submitted plagiarized thesis. -

Cultural Profile of Gandhāra: an Appraisal

CULTURAL PROFILE OF GANDHĀRA: AN APPRAISAL by Tauqeer Ahmad INSTITUTE OF ARCHAEOLOGY AND ANTHROPOLOGY FACULTY OF ARTS AND HUMANITIES UNIVERSITY OF PESHAWAR 2011 CULTURAL PROFILE OF GANDHĀRA: AN APPRAISAL Dissertation submitted to the Institute of Archaeology and Social Anthropology, University of Peshawar in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Approved by: 1. Professor Dr. M. Farooq Swati Institute of Archaeology & Social Anthropology, University of Peshawar Supervisor 2. Internal Examiner 3. External Examiner INSTITUTE OF ARCHAEOLOGY AND ANTHROPOLOGY UNIVERSITY OF PESHAWAR 2011 i Contents List Abbreviations Map List of Illustrations Acknowledgement Chapter 1: Introduction Discovery and Interpretation of the name Discovery of Gandhāra Art Development of Archaeological activities Phase 1 Phase 11 Phase 111 Chapter 2: Historical Background Physical Setup Gandhāra: Meaning History: Achaemenians Alexander’s invasion Mauriyan rule Occupation of Bactrian Greeks Indo-Scytho-Parthians Kushāns Huns or Ephthalites Chapter 3: Gandhāra Art Independent Cult Images Non-Buddhist Deities Relief Penals Chapter 4: Architecture i. Secular Buildings Cities ii Forts and Citadel Palaces ii. Religious Buildings Stupa Vihāra and Shrines Chaitya Fire Atar Chapter 5: Weapons, Tool, Implements and Garments i. Weapons Club Spear Triśula Sword Dagger Archery Battle-axe Armour ii. Tools and Implements Garments Buddha Bodhisattva Royality Priests, Ascetics and Monks Deities Miscellanious Chapter 6: Jewellery and Headdresses i. Jewellery Head Ornaments Necklaces Earrings and Ear Pendants Armlets Bracelets iii Anklets ii. Headdresses Śakyāmuni Brahmā Bodhisattva Turban Styles 1-V11 Jaṭāmukuṭ Fashions Chapter 7: Miscellenious i. Household Vessel ii. Musical Instruments Drum Cymbal Gong Bell Harp Lyre iii. Wind Instruments iv.