Book Review: Kurt A. Behrendt: the Buddhist Architecture of Gandhāra

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gandharan Origin of the Amida Buddha Image

Ancient Punjab – Volume 4, 2016-2017 1 GANDHARAN ORIGIN OF THE AMIDA BUDDHA IMAGE Katsumi Tanabe ABSTRACT The most famous Buddha of Mahāyāna Pure Land Buddhism is the Amida (Amitabha/Amitayus) Buddha that has been worshipped as great savior Buddha especially by Japanese Pure Land Buddhists (Jyodoshu and Jyodoshinshu schools). Quite different from other Mahāyāna celestial and non-historical Buddhas, the Amida Buddha has exceptionally two names or epithets: Amitābha alias Amitāyus. Amitābha means in Sanskrit ‘Infinite light’ while Amitāyus ‘Infinite life’. One of the problems concerning the Amida Buddha is why only this Buddha has two names or epithets. This anomaly is, as we shall see below, very important for solving the origin of the Amida Buddha. Keywords: Amida, Śākyamuni, Buddha, Mahāyāna, Buddhist, Gandhara, In Japan there remain many old paintings of the Amida Triad or Trinity: the Amida Buddha flanked by the two bodhisattvas Avalokiteśvara and Mahāsthāmaprāpta (Fig.1). The function of Avalokiteśvara is compassion while that of Mahāsthāmaprāpta is wisdom. Both of them help the Amida Buddha to save the lives of sentient beings. Therefore, most of such paintings as the Amida Triad feature their visiting a dying Buddhist and attempting to carry the soul of the dead to the AmidaParadise (Sukhāvatī) (cf. Tangut paintings of 12-13 centuries CE from Khara-khoto, The State Hermitage Museum 2008: 324-327, pls. 221-224). Thus, the Amida Buddha and the two regular attendant bodhisattvas became quite popular among Japanese Buddhists and paintings. However, the origin of this Triad and also the Amida Buddha himself is not clarified as yet in spite of many previous studies dedicated to the Amida Buddha, the Amida Triad, and the two regular attendant bodhisattvas (Higuchi 1950; Huntington 1980; Brough 1982; Quagliotti 1996; Salomon/Schopen 2002; Harrison/Lutczanits 2012; Miyaji 2008; Rhi 2003, 2006). -

Mon Buddhist Architecture in Pakkret District, Nonthaburi Province, Thailand During Thonburi and Rattanakosin Periods (1767-1932)

MON BUDDHIST ARCHITECTURE IN PAKKRET DISTRICT, NONTHABURI PROVINCE, THAILAND DURING THONBURI AND RATTANAKOSIN PERIODS (1767-1932) Jirada Praebaisri* and Koompong Noobanjong Department of Industrial Education, Faculty of Industrial Education and Technology, King Mongkut's Institute of Technology Ladkrabang, Bangkok 10520, Thailand *Corresponding author: [email protected] Received: October 3, 2018; Revised: February 22, 2019; Accepted: April 17, 2019 Abstract This research examines the characteristics of Mon Buddhist architecture during Thonburi and Rattanakosin periods (1767-1932) in Pakkret district. In conjunction with the oral histories acquired from the local residents, the study incorporates inquiries on historical narratives and documents, together with photographic and illustrative materials obtained from physical surveys of thirty religious structures for data collection. The textual investigations indicate that Mon people migrated to the Siamese kingdom of Ayutthaya in large number during the 18th century, and established their settlements in and around Pakkret area. Located northwest of the present day Bangkok in Nonthaburi province, Pakkret developed into an important community of the Mon diasporas, possessing a well-organized local administration that contributed to its economic prosperity. Although the Mons was assimilated into the Siamese political structure, they were able to preserve most of their traditions and customs. At the same time, the productions of their cultural artifacts encompassed many Thai elements as well, as evident from Mon Buddhist temples and monasteries in Pakkret. The stylistic analyses of these structures further reveal the following findings. First, their designs were determined by four groups of patrons: Mon laypersons, elite Mons, Thai Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences Studies Vol.19(1): 30-58, 2019 Mon Buddhist Architecture in Pakkret District Praebaisri, J. -

Phase Iii Architecture and Sculpture from Taxila 6.1

CHAPTER SIX PHASE III ARCHITECTURE AND SCULPTURE FROM TAXILA 6.1 Introduction to the Phase III Developments in the Sacred Areas and Afonasteries ef Taxila and the Peshawar Basin A dramatic increase in patronage occurred across the Peshawar basin, Taxila, and Swat during phase III; most of the extant remains in these regions were constructed at this time. As devotional icons of Buddhas and bodhisattvas became increasingly popular, parallel trans formations occurred in the sacred areas, which still remained focused around relic stupas. In the Peshawar basin, Taxila, and to a lesser degree Swat, the widespread incorporation of large iconic images clearly reflects changes occurring in Buddhist practice. Although it is difficult to know how the sacred precincts were ritually used, modifications in the spatial organization of both sacred areas and monasteries provide some insight. Not surprisingly, the use and incorporation of devotional images developed regionally. The most dramatic shift toward icons is observed in the Peshawar basin and some of the Taxila sites. In contrast, Swat seemed to follow a different pattern, as fewer image shrines were fabricated and sacred areas were organized along different lines. This might reflect a lack of patronage; perhaps new sites following the Peshawar basin format were not commissioned because of a lack of resources. More likely, the Buddhist tradition in Swat was of a different character; some sites-notably Butkara I-show significant expansion following a uniquely Swati format. At a few sites in Swat, however, image shrines appear in positions analogous to those of the Peshawar basin; Nimogram and Saidu (figs. 109, 104) arc notable examples. -

Buddhist Art and Architecture Ebook

BUDDHIST ART AND ARCHITECTURE PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Robert E Fisher | 216 pages | 24 May 1993 | Thames & Hudson Ltd | 9780500202654 | English | London, United Kingdom GS Art and Culture | Buddhist Architecture | UPSC Prep | NeoStencil Mahabodhi Temple is an example of one of the oldest brick structures in eastern India. It is considered to be the finest example of Indian brickwork and was highly influential in the development of later architectural traditions. Bodhgaya is a pilgrimage site since Siddhartha achieved enlightenment here and became Gautama Buddha. While the bodhi tree is of immense importance, the Mahabodhi Temple at Bodhgaya is an important reminder of the brickwork of that time. The Mahabodhi Temple is surrounded by stone ralling on all four sides. The design of the temple is unusual. It is, strictly speaking, neither Dravida nor Nagara. It is narrow like a Nagara temple, but it rises without curving, like a Dravida one. The monastic university of Nalanda is a mahavihara as it is a complex of several monasteries of various sizes. Till date, only a small portion of this ancient learning centre has been excavated as most of it lies buried under contemporary civilisation, making further excavations almost impossible. Most of the information about Nalanda is based on the records of Xuan Zang which states that the foundation of a monastery was laid by Kumargupta I in the fifth century CE. Vedika - Vedika is a stone- walled fence that surrounds a Buddhist stupa and symbolically separates the inner sacral from the surrounding secular sphere. Talk to us for. UPSC preparation support! Talk to us for UPSC preparation support! Please wait Free Prep. -

Gandharan Sculptures in the Peshawar Museum (Life Story of Buddha)

Gandharan Sculptures in the Peshawar Museum (Life Story of Buddha) Ihsan Ali Muhammad Naeem Qazi Hazara University Mansehra NWFP – Pakistan 2008 Uploaded by [email protected] © Copy Rights reserved in favour of Hazara University, Mansehra, NWFP – Pakistan Editors: Ihsan Ali* Muhammad Naeem Qazi** Price: US $ 20/- Title: Gandharan Sculptures in the Peshawar Museum (Life Story of Buddha) Frontispiece: Buddha Visiting Kashyapa Printed at: Khyber Printers, Small Industrial Estate, Kohat Road, Peshawar – Pakistan. Tel: (++92-91) 2325196 Fax: (++92-91) 5272407 E-mail: [email protected] Correspondence Address: Hazara University, Mansehra, NWFP – Pakistan Website: hu.edu.pk E-mail: [email protected] * Professor, Department of Archaeology, University of Peshawar, Currently Vice Chancellor, Hazara University, Mansehra, NWFP – Pakistan ** Assistant Professor, Department of Archaeology, University of Peshawar, Pakistan CONTRIBUTORS 1. Prof. Dr. Ihsan Ali, Vice Chancellor Hazara University, Mansehra, Pakistan 2. Muhammad Naeem Qazi, Assistant Professor, Department of Archaeology, University of Peshawar, Pakistan 3. Ihsanullah Jan, Lecturer, Department of Cultural Heritage & Tourism Management, Hazara University 4. Muhammad Ashfaq, University Museum, Hazara University 5. Syed Ayaz Ali Shah, Department of Archaeology, University of Peshawar, Pakistan 6. Abdul Hameed Chitrali, Lecturer, Department of Cultural Heritage & Tourism Management, Hazara University 7. Muhammad Imran Khan, Archaeologist, Charsadda, Pakistan 8. Muhammad Haroon, Archaeologist, Mardan, Pakistan III ABBREVIATIONS A.D.F.C. Archaeology Department, Frontier Circle A.S.I. Archaeological Survery of India A.S.I.A.R. Archaeological Survery of India, Annual Report D.G.A. Director General of Archaeology E.G.A.C. Exhibition of the German Art Council I.G.P. Inspector General Police IsMEO Instituto Italiano Per il Medio ed Estremo Oriente P.M. -

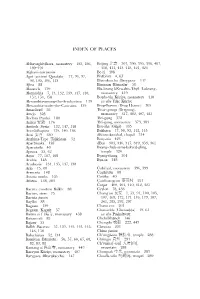

Index of Places

INDEX OF PLACES Abhayagirivihra, monastery 185, 186, Beijing 北京 307, 390, 395, 396, 407, 189–191 410, 411, 413–418, 421, 424 Afghanistan passim Be-ri 408 Agni (ancient Qaraahr) 77, 94, 97, Bhbhr 4, 63 98, 105, 106, 113 Bharukaccha (Barygaza) 147 Aúina 88 Bimaran (Bimarn) 58 Alasanda 139 Bla-brang bKra-shis-’khyil (Labrang), Alexandria 7, 13, 132, 139, 147, 148, monastery 419 152, 154, 158 Boda-yin Küriye, monastery 418 Alexandria-among-the-Arachosians 139 see also Yeke Küriye Alexandria-under-the-Caucasus 139 Brag-lha-mo (Drag Lhamo) 305 Amarvat 58 ’Bras-spungs (Drepung), Amdo 328 monastery 317, 402, 407, 425 Undhra Prade 180 ’Bri-gung 372 Anhui 安徽 176 ’Bri-gung, monastery 373, 383 Antioch (Syria) 132, 147, 148 Bru-sha (Gilgit) 335 Anurdhapura 139, 140, 186 Bukhara 77, 90, 93, 142, 145 Anxi 安西 330 dBu-ru-ka-tshal, chapel 314 Anzhina-Tepe (Tajikistan) 52 Buryatia 423 Aparntaka 138 dBus 304, 346, 347, 349, 353, 361 Aparaaila 40 Byang-chub-sems-bskyed-gling, Apraca 55, 62 temple 324 Aqsu 77, 107, 108 Byang-thang 304 Arabia 148 Bya-sa 348 Arachosia 134, 135, 137, 138 Aria 75, 80 ab iyal, monastery 396, 399 Armenia 148 anyn 88 Astana tombs 105 Caitika 40 Athens 148, 203 Caizhuangcun 蔡莊村 221 aqar 400, 401, 410, 412, 425 Bactres (modern Balkh) 88 Ceylon 78, 436 Bactres, river 75 Chang’an 長安 1, 53, 91, 100, 105, Bactria passim 107, 168, 172, 174–176, 179, 187, Baln 88 261, 285, 292, 297 Bagrm 139 Characene 203 Begram (Kap ) 57 Charsadda (Charsa a) 49, 61 Baima si 白馬寺, monastery 438 see also Pukalvat Bairam-ali 83 Chehelkhneh 146 Bajaur 55 Chengdu -

Palatial Symbolism in the Buddhist Architecture of Early Medieval China

Front. Hist. China 2015, 10(2): 222–263 DOI 10.3868/s020-004-015-0014-1 RESEARCH ARTICLE Tracy Miller Of Palaces and Pagodas: Palatial Symbolism in the Buddhist Architecture of Early Medieval China Abstract This paper is an inquiry into possible motivations for representing timber-frame architecture in the Buddhist context. By comparing the architectural language of early Buddhist narrative panels and cave temples rendered in stone, I suggest that architectural representation was employed in both masonry and timber to create symbolically charged worship spaces. The replication and multiplication of palace forms on cave walls, in “pagodas” (futu 浮圖, fotu 佛圖, or ta 塔), and as the crowning element of free-standing pillars reflect a common desire to express and harness divine power, a desire that resulted in a wide variety of mountainous monuments in China. Finally, I provide evidence to suggest that the towering Buddhist monuments of early medieval China are linked morphologically and symbolically to the towering temples of South Asia through the use of both palace forms and sacred ma alas as a means to express the divine power and expansive presence of the Buddha. Keywords Pagoda, ta, mandala, Sumeru, Yicihui pillar, Yongningsi, Songyuesi From South to East Asia, from narrative relief panels to surface decoration both in caves and freestanding worship spaces, Buddhist sites are replete with depictions of timber buildings. Narrative reliefs not only allow us to read the story of the life of the Buddha, they also provide a window into the visual language of the region in which the panels were produced. -

Geographical Differences and Similarities in Gandhāran Sculptures ��������������������������������������������41 Satoshi Naiki Part 2 Provenances and Localities

The Geography of Gandhāran Art Proceedings of the Second International Workshop of the Gandhāra Connections Project, University of Oxford, 22nd-23rd March, 2018 Edited by Wannaporn Rienjang Peter Stewart Archaeopress Archaeology Archaeopress Publishing Ltd Summertown Pavilion 18-24 Middle Way Summertown Oxford OX2 7LG www.archaeopress.com ISBN 978-1-78969-186-3 ISBN 978-1-78969-187-0 (e-Pdf) DOI: 10.32028/9781789691863 © Archaeopress and the individual authors 2019 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright owners. This book is available direct from Archaeopress or from our website www.archaeopress.com Contents Acknowledgements ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������iii Editors’ note �����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������iii Contributors ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� iv Preface ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� ix Wannaporn Rienjang and Peter Stewart Part 1 Artistic Geographies Gandhāran art(s): methodologies and preliminary results of a stylistic analysis ������������������������� 3 Jessie Pons -

Buddhism and the Global Bazaar in Bodh Gaya, Bihar

DESTINATION ENLIGHTENMENT: BUDDHISM AND THE GLOBAL BAZAAR IN BODH GAYA, BIHAR by David Geary B.A., Simon Fraser University, 1999 M.A., Carleton University, 2003 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in The Faculty of Graduate Studies (Anthropology) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) December 2009 © David Geary, 2009 ABSTRACT This dissertation is a historical ethnography that examines the social transformation of Bodh Gaya into a World Heritage site. On June 26, 2002, the Mahabodhi Temple Complex at Bodh Gaya was formally inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List. As a place of cultural heritage and a monument of “outstanding universal value” this inclusion has reinforced the ancient significance of Bodh Gaya as the place of Buddha's enlightenment. In this dissertation, I take this recent event as a framing device for my historical and ethnographic analysis that details the varying ways in which Bodh Gaya is constructed out of a particular set of social relations. How do different groups attach meaning to Bodh Gaya's space and negotiate the multiple claims and memories embedded in place? How is Bodh Gaya socially constructed as a global site of memory and how do contests over its spatiality im- plicate divergent histories, narratives and events? In order to delineate the various historical and spatial meanings that place holds for different groups I examine a set of interrelated transnational processes that are the focus of this dissertation: 1) the emergence of Buddhist monasteries, temples and/or guest houses tied to international pilgrimage; 2) the role of tourism and pilgrimage as a source of economic livelihood for local residents; and 3) the role of state tourism development and urban planning. -

Total Syllabus, AIH & Archaeoalogy, Lucknow University

Department of Ancient Indian History and Archaeology, University of Lucknow, Lucknow B.A. Part - I Paper I : Political History of Ancient India (from c 600 BC to c 320 AD) Unit I 1. Sources of Ancient Indian history. 2. Political condition of northern India in sixth century BC- Sixteen mahajanapadas and ten republican states. 3. Achaemenian invasion of India. 4. Rise of Magadha-The Bimbisarids and the Saisunaga dynasty. 5. Alexander’s invasion of India and its impact. Unit II 1. The Nanda dynasty 2. The Maurya dynasty-origin, Chandragupta, Bindusara 3. The Maurya dynasty-Asoka: Sources of study, conquest and extent of empire, policy of dhamma. 4. The Maurya dynasty- Successors of Asoka, Mauryan Administration. The causes of the downfall of the dynasty. Unit III 1. The Sunga dynasty. 2. The Kanva dynasty. 3. King Kharavela of Kalinga. 4. The Satavahana dynasty. 1 Unit IV 1. The Indo Greeks. 2. The Saka-Palhavas. 3. The Kushanas. 4. Northern India after the Kushanas. PAPER– II: Social, Economic & Religious Life in Ancient India UNIT- I 1. General survey of the origin and development of Varna and Jati 2. Scheme of the Ashramas 3. Purusharthas UNIT- II 1. Marriage 2. Position of women 3. Salient features of Gurukul system- University of Nalanda UNIT- III 1. Agriculture with special reference to the Vedic Age 2. Ownership of Land 3. Guild Organisation 4. Trade and Commerce with special reference to the 6th century B.C., Saka – Satavahana period and Gupta period UNIT- IV 1. Indus religion 2. Vedic religion 3. Life and teachings of Mahavira 4. -

Posthumous Azes Coins in Stupa Deposits from Ancient Afghanistan

Posthumous Azes Coins In stupa deposits from ancient Afghanistan ONS 2 March 2013 ‘Donation of Śivarakṣita, son of Mujavada, offered with relics of the Lord, in honour of all buddhas’ Deposits from Bimaran 2 stupa with the gold casket and Posthumous Azes coins Courtesy of Piers Baker Shevaki Stupa, Kabul Courtesy of Piers Baker Shevaki Stupa from afar Courtesy of Piers Baker Guldara Stupa, Kabul The ‘Indo-Scythians’ kings and satraps in coin sequences (Based on Errington & Curtis 2007) Kings Satraps Basileos / Maharaja Satrap, Strategos / Chatrap Maues (c.75-65BC) Kharahostes (early 1st AD) Vonones (c.65-50BC) Zeionises (c.AD30-50) Spalyrises (c.50-40BC) Rajavula Azes I (c.46-1BC) Aspavarma (c.AD33-64)* Azilises (c.1BC-AD16) * With the name ‘Azes’ on the obverse Azes II (c.16-30AD) Indo-Scythian coins from Buddhist sites in ancient Pakistan and Afghanistan (Based on Errington 1999/2000) Swat Darunta/Jalalabad/ Peshawar Hadda Taxila Posthumous Azes Maues c.75-65BC Azilises c.1BC-AD16 Zeionises c.AD30-50 Vonones c.65-50BC Azes II c.AD16-30 Rajavula Azes I c.46-1BC Kharahostes early 1st AD Aspavarma c.AD33-64 Pontic to Central Asian steppes Iranian Plateau Arabia Nomadic and sedentary groups living in areas extending from the Pontic to Central Asian steppes during the first millennium BC ‘Σκυϑοι’ in Greek sources / ‘Sakas’ in Iranian sources ‘Śakas’ in Indian sources / ‘Sai’ or ‘Se’ in Chinese sources Three types of Sakas according to the Naqš-i-Rustam inscription of Darius I Sakas ‘who are across the sea’ (Saka Paradraya) The Pontic steppe -

Catalog and Revised Texts and Translations of Gandharan Reliquary Inscriptions

Chapter 6 Catalog and revised texts and translations of gandharan reliquary inscriptions steFan baums the Gandharan reliquary inscriptions cataloged and addition to or in place of these main eras, regnal translated in this chapter are found on four main types years of a current or (in the case of Patika’s inscrip- of objects: relic containers of a variety of shapes, thin tion no. 12) recent ruler are used in dating formulae, gold or silver scrolls deposited inside reliquaries, and detailed information is available about two of the thicker metal plates deposited alongside reliquaries, royal houses concerned: the kings of Apraca (family and stone slabs that formed part of a stūpa’s relic tree in Falk 1998: 107, with additional suggestions in chamber or covered stone reliquaries. Irrespective Salomon 2005a) and the kings of Oḍi (family tree in of the type of object, the inscriptions follow a uniform von Hinüber 2003: 33). pattern described in chapter 5. Three principal eras In preparing the catalog, it became apparent that are used in the dating formulae of these inscriptions: not only new and uniform translations of the whole the Greek era of 186/185 BCE (Salomon 2005a); the set of inscriptions were called for, but also the texts Azes (= Vikrama) era of 58/57 BCE (Bivar 1981b);1 themselves needed to be reconstituted on the basis and the Kanishka era of c. 127 CE (Falk 2001). In of numerous individual suggestions for improvements made after the most recent full edition of each text. All these suggestions (so far as they could be traced) 1.