Samuel Beckett and Em Cioran

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Curriculum Vitae

JOSEPH ACQUISTO Professor of French Chair, Department of Romance Languages and Linguistics University of Vermont 517 Waterman Building Burlington, VT 05405 [email protected] (802) 656-4845 EDUCATION Yale University Ph.D., Department of French (2003) M.Phil., French (2000) M.A., French (1998) University of Dayton B.A., summa cum laude, French (1997) B.Mus., summa cum laude, voice performance (1997) EMPLOYMENT HISTORY Chair, Department of Romance Languages and Linguistics, University of Vermont 2016-present Professor of French, University of Vermont 2014-present Associate Professor of French with tenure, University of Vermont 2009-2014 Assistant Professor of French, University of Vermont 2003-2009 BOOKS 7. Poetry’s Knowing Ignorance, under consideration 6. Proust, Music, and Meaning: Theories and Practices of Listening in the Recherche, New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017. 5. The Fall Out of Redemption: Writing and Thinking Beyond Salvation in Baudelaire, Cioran, Fondane, Agamben, and Nancy. New York: Bloomsbury, 2015. Paperback edition 2016. 4. Poets as Readers in Nineteenth-Century France: Critical Reflections, co-edited volume with Adrianna M. Paliyenko and Catherine Witt. London: Institute of Modern Languages Research, 2015. 3. Thinking Poetry: Philosophical Approaches to Nineteenth-Century French Poetry, edited volume. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013. 1 2. Crusoes and Other Castaways in Modern French Literature: Solitary Adventures. Newark: University of Delaware Press, 2012. Paperback edition 2014. 1. French Symbolist Poetry and the Idea of Music. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2006. EDITED SPECIAL ISSUE The Cultural Currency of Nineteenth-Century French Poetry, a special double issue of Romance Studies (26:3-4, July/November 2008) co-edited and prefaced with Adrianna M. -

A New Decade for Social Changes

Vol. 21, 2021 A new decade for social changes ISSN 2668-7798 www.techniumscience.com 9 772668 779000 Technium Social Sciences Journal Vol. 21, 846-852, July, 2021 ISSN: 2668-7798 www.techniumscience.com The concept of transcendence in philosophy and theology Petrov George Daniel Theology Faculty, Ovidius University – Constanța, România [email protected] Abstract. The transcendence of God is the most sensitive and profound subject that could be addressed by the most enlightened minds of the world. In sketching this concept, the world of philosophy and that of theology are trying the impossible: to define the Absolute. Each approach is different, the first being subjected to reason, reaching specific conclusions, and the second, by understanding God's Personal character, appealing to the experience of living your life in God. The debate between the two worlds, that of philosophy and that of theology can only bring a plus to knowledge, while impressing any wisdom lover. Keywords. God, transcendence, immanence, Plato, Cioran, Heidegger, Hegel, Stăniloae I. Introduction The concept of transcendence expresses its importance through its ability to attract the intellect into deep research, out of a desire to express the inexpressible. The God of Theology was often named and defined by the world of philosophy in finite words, that could not encompass the greatness of the inexpressible. They could, however, rationally describe the Divinity, based on the similarities between the divine attributes and those of the world. Thus, in the world of great thinkers, God bears different names such as The Prime Engine, out of a desire to highlight the moment zero of time, Absolute Identity and even Substance, to express the immateriality of the Cause of all causes. -

Emil Cioran – a Deconstructive Philosophy

EMIL CIORAN – A DECONSTRUCTIVE PHILOSOPHY Angela Botez∗∗∗ [email protected] Abstract: For Cioran, expressing (something, someone) is the same with a postponed ripost or an aggression left for lateron and his writing is a solution, not to act, to avoid a crisis. His indignation is not as much a moral outset, as it is a literary one, the resort of inspiration, while wisdom wearies us of any momentum. The writer is a lunatic who uses in curative purposes these fictions we call words. For the Romanian philosopher the most uncomfortable relation is precisely with philosophy explaining that meeting the idea face to face incites us to talk nonsense, and clouds our judgement and produces the illusion of almightiness... All our deregulations and aberrations are triggered by the fight we lead with the irrealities, with the abstractions, with our will to conquer what does not exist, and from hereon also the impure, tiranical and delirious aspect of the philosophical works... Keywords: Emil Cioran, deconstructivism, antifoundationalism, philosophy of life, despair, and end of philosophy. Among the Romanian philosophers, the most explicit postmodern position of a deconstructive nihilistic type was Emil Cioran. In his work Exercises d’admiration: essais et portraits,1 published in the Romanian version by the Humanitas Publishing House in 1993, there is an article entitled Relecturing, resulted, according to the confession of the author, from the intention to present to the German readers his Précis de décomposition translated from French to German by Paul Celan, in 1953, and edited in 1978. The text gives a glimpse of the type of philosophy promoted by Emil Cioran, inscribed, obviously, among the postmodernist, antifoundationalist, nihilist, and deconstructivist tendencies. -

South Pacific

THE MUSICO-DRAMATIC EVOLUTION OF RODGERS AND HAMMERSTEIN’S SOUTH PACIFIC DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By James A. Lovensheimer, M.A. ***** The Ohio State University 2003 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Arved Ashby, Adviser Professor Charles M. Atkinson ________________________ Adviser Professor Lois Rosow School of Music Graduate Program ABSTRACT Since its opening in 1949, Rodgers and Hammerstein’s Pulitzer Prize- winning musical South Pacific has been regarded as a masterpiece of the genre. Frequently revived, filmed for commercial release in 1958, and filmed again for television in 2000, it has reached audiences in the millions. It is based on selected stories from James A. Michener’s book, Tales of the South Pacific, also a Pulitzer Prize winner; the plots of these stories, and the musical, explore ethnic and cutural prejudice, a theme whose treatment underwent changes during the musical’s evolution. This study concerns the musico-dramatic evolution of South Pacific, a previously unexplored process revealing the collaborative interaction of two masters at the peak of their creative powers. It also demonstrates the authors’ gradual softening of the show’s social commentary. The structural changes, observable through sketches found in the papers of Rodgers and Hammerstein, show how the team developed their characterizations through musical styles, making changes that often indicate changes in characters’ psychological states; they also reveal changing approaches to the musicalization of the novel. Studying these changes provides intimate and, occasionally, unexpected insights into Rodgers and Hammerstein’s creative methods. -

The Benefits of Being a Suicidal Curmudgeon: Emil Cioran on Killing Yourself

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Faculty Scholarship 1-2021 The Benefits of Being a Suicidal Curmudgeon: Emil Cioran on Killing Yourself Glenn M. Trujillo Jr University of Louisville, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/faculty Part of the Philosophy Commons Original Publication Information Trujillo, Jr., G.M. "The Benefits Of Being A Suicidal Curmudgeon: Emil Cioran On Killing Yourself." 2021. Southwest Philosophy Review 37(1): 219-228. ThinkIR Citation Trujillo, Glenn M. Jr, "The Benefits of Being a Suicidal Curmudgeon: Emil Cioran on Killing Yourself" (2021). Faculty Scholarship. 535. https://ir.library.louisville.edu/faculty/535 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Benefi ts of Being a Suicidal Curmudgeon: Emil Cioran on Killing Yourself G. M. Trujillo, Jr. University of Louisville Abstract: Emil Cioran offers novel arguments against suicide. He assumes a meaningless world. But in such a world, he argues, suicide and death would be equally as meaningless as life or anything else. Suicide and death are as cumbersome and useless as meaning and life. Yet Cioran also argues that we should contemplate suicide to live better lives. By contemplating suicide, we confront the deep suffering inherent in existence. This humbles us enough to allow us to change even the deepest aspects of ourselves. -

After Images of the Present. Utopian Imagination In

Revista de Estudios Globales y Arte Contemporáneo | Vol. 4 | Núm. 1 | 2016 | 340-362 Nadja Gnamuš University of Primorska Koper, Slovenia AFTER IMAGES OF THE PRESENT. UTOPIAN IMAGINATION IN CONTEMPORARY ART PRACTICES Whatever we do, it could be different. The painting of a picture is never finished; the writing of a book is never completed. The conclusion of what we have just printed out could still be changed. And if it came to that, then the effort would start from the beginning.1 The introductory quote is taken from Ernst Bloch's short essay on the humanist and political writings of Berthold Brecht. "Brecht wants to change the audience itself through his products, so the changed audience […] also 1 Bloch, E. (1938). A Leninist of the Stage. Heritage of Our Times (1991). Cambridge: Polity Press, p. 229. Revista de Estudios Globales y Arte Contemporáneo ISSN: 2013-8652 online http://revistes.ub.edu/index.php/REGAC/index Schulz-Ohm, M. | Living a Utopia. The Artist’s House as a Total Work of Art has retroactive effect on the products".2 This would be the ideal effect of an artwork engaging in real social life and actively transforming it. The desire to change the world into a better, freer, and balanced place is not just the driving force of critical and socially engaged actions but also an immanent feature of utopian thought. However, this ideal and accomplished social whole (as imagined by the historical avant-gardes) is evasive and not yet to be attained. It is non-existent or ou-topic on the map of reality. -

CONTACT, the Phoenix Project, November 9, 1993

CONTACT THE PHOENIX PROJECT “YE SHALL KNOW THE TRUTH AND THE TRUTH SHALL MAKE YOU MAD.!” VOLUME 3, NUMBER 7 NEWS REVIEW ,I $ 2.00 NOVEMBER 9, 1993 Gov. Carnahan: We’re Mad As Hell WE WON'T TAKE IT MUCH LONGER! 1117193 #l HATONN in every category. We suggest that you pure excitement, monetary gain, “I Spy”, to NOT BE LISTED AMONG THOSE CRIMI- total devotion to our nation, the United “We” may be a small paper but we ARE NALS, SIR. If, indeed, you do not know States of America. We are not given the the voice of the people of this nation, under about this atrocity in your dooryard-that right to judge reasons-only performance GOD who proclaims freedom and justice you find out lest you be painted with the and mistreatment at the hands of those for ALL. We are going to turn this focus of same black brush of disregard for all jus- put in office TO PROTECT OUR FREEDOM light onto you and the judicial non-system tice and order in our once great nation. AND RIGHTS UNDER THE CONSTITU- of Missouri, Sir, until you let Gunther If, Sir, you do not feel capable of acting TIONS OF OUR STATES AND NATION. Russbacher go. You HAVE all the informa- as a Governor of a great State, then we Puppet-masters? The higher echelon of tion regarding this servant of our govern- suggest you ask your puppet-masters about misrepresentation of We-The-People-the ment who is now sick and possibly dying in the seriousness of this incarceration con- very ones involved directly-the Kissinger-s, your State Prison simply to maintain his tinuing. -

Anthropos?, Issue: 16-17 / 2011 — Dom- Na Szczytach Lokalności

Dom na szczytach lokalności «Homeat the Heights of Locality» by Aleksandra Kunce Source: Anthropos? (Anthropos?), issue: 1617 / 2011, pages: 4558, on www.ceeol.com. The following ad supports maintaining our C.E.E.O.L. service Access via CEEOL NL Germany Aleksandra Kunce Dom - na szczytach lokalno ści [*] Przedmiotem moich rozwa Ŝań b ędzie lokalno ść , człowiek lokalny, Ŝycie lokalnie pojmowane. Chc ę jednak rozpatrywa ć to, co lokalne nie w nawi ązaniu do tego, co niskie, co podporz ądkowane czemu ś globalnemu, ale jako to, co zawsze istnieje na szczytach naszego do świadczania i rozumienia egzystencji. Kiedy Emil Cioran, w 1934 roku pisał, jeszcze po rumu ńsku, swój wa Ŝny tekst "Na szczytach rozpaczy" miał na my śli egzystencj ę, która jest niepohamowanym intensywnym wzrostem, "płodnym płomieniem", w którym nast ępuje skomplikowanie tre ści duchowych i w którym wszystko pulsuje z niesłychanym napi ęciem [1] . Bycie na szczytach rozpaczy jest egzystencj ą dramatyczn ą. Chc ę pojmowa ć lokalne bycie i lokalne uło Ŝenie człowieka jako bycie na szczytach do świadczenia . Ale tu napotykam pewne przeszkody. 1. Rozumienie lokalno ści mo Ŝe mie ć niebezpieczne i ciasne obszary. Wi ąŜą si ę one z etniczno ści ą. Podstawowa obawa jest taka: Czy do obja śnienia ludzkiego losu naprawd ę potrzeba reguły etnicznej? Ale i inna: Czy ogóle da si ę rozumie ć człowieka bez odwołania etnicznego? Grecki termin "ethnos" to z jednej strony pewna liczba osób, które Ŝyj ą razem, plemi ę; z drugiej strony to stada ptaków, zwierz ąt; po Homerze to równie Ŝ naród, lud; a jeszcze pó źniej obce, barbarzy ńskie ludy, czyli nie-Ate ńczycy, biblijna greka uczy, Ŝe to nie-śydzi, poganie, ale te Ŝ kasta, klasa ludzi, plemi ę[2] . -

The Postmodern Self in Thomas Pynchon's the Crying of Lot 49

AKADEMIN FÖR UTBILDNING OCH EKONOMI Avdelningen för humaniora The Postmodern self in Thomas Pynchon's the Crying of Lot 49 Dismantling the unified self by a combination of postmodern philosophy and close reading Andreas Signell 2015-16 Uppsats, Grundnivå (Studentarbete övrigt) 15 hp Engelska med ämnesdidaktisk inriktning (61-90) Ämneslärarprogrammet med inriktning mot arbete i gymnasieskolan 0030 Uppsats Handledare: Iulian Cananau, PhD Examinator: Marko Modiano, docent Abstract This essay is about identity and the self in Thomas Pynchon's critically acclaimed masterpiece The Crying of Lot 49. Through a combination of postmodern philosophy and close reading, it examines instances of postmodernist representations of identity in the novel. The essay argues that Pynchon is dismantling the idea of a unified self and instead argues for and presents a postmodern take on identity in its place. Questions asked by the essay are: in what ways does Pynchon criticize the idea of a unified self? What alternatives to this notion does Pynchon present? The essay is split into six chapters, an introductory section followed by a background on Thomas Pynchon and the novel. This is followed by an in-depth look into postmodernism, and Ludwig Wittgenstein's importance for it, as well as the basic concepts of his philosophy. This is followed by the main analysis in which a myriad of segments and quotations from the novel are looked at. Lastly, this is followed by a summarizing conclusion. The essay assumes a postmodernist approach of not being a definitive answer; rather it is one voice among many in the community of Pynchon interpreters. -

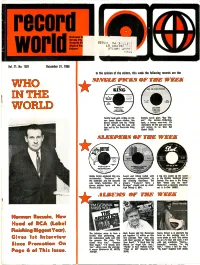

W Ho in the W Orld

0S9S I Vd 35OUIV1 IS inti m:, soa MDrUV(.3 A8klY9 Ue—C) 'Jo!. , No. 1021 December 31, 1966 In the opinion of the editors, this week the following records are the * SINGLE PICKS OF 111E W EEK W HO KING IN THE LAT TRIPPER VA, W ORLD 11/01 novnii TM FAMOUS RA MS Terrific beat gets rolling on the Ramsey Lewis gives "Day Trip- new James Brown release. Guy per," the Lennon McCartney throws himself into his "Bring opus, a breezy once-over. It's It Up" ditty and the kids will dancetime for the guy and sales turn out by the thous7nds (King will accrue in no time flat CUR (Cadet 5553). SLEEPERS OF THE W EE K Bobby Vinton produced this new Sweet and lilting ballad with A big new sound on the scene instrumental, "Bodacious" by contemporary arrangement by is the Charles Randolph Crean the Satellites and the outcome the climbing Stairsteps. The Sounde. The ti.ne is the Proko- was simply bod3cious. It's a group's "Danger She's a fieff "Peter and the Wolf" groovy number teens will like Stranger" should end up chart- theme i-nd a raunchi y attractive (13:-..rrot 313). Ugh (Windy C 6041. cut it is (Dot 16982). .1 t itl'IlS OF THE W EEK Norman Racusin, New Head of RCA (Label Finishing Biggest Year), The Artistics seem to have a Buck Owens and the Buckaroos Nancy Wilson is in absolute top terrific time performing, and put together 12 nifties on this form on this package (and in Gives 1st Interview the enthusiasm spills over into new package. -

Francis Bacon: the Logic of Sensation

Francis Bacon: the logic of sensation GILLES DELEUZE Translated from the French by Daniel W. Smith continuum LONDON • NEW YORK This work is published with the support of the French Ministry of Culture Centre National du Livre. Liberte • Egalite • Fraternite REPUBLIQUE FRANCAISE This book is supported by the French Ministry for Foreign Affairs, as part of the Burgess programme headed for the French Embassy in London by the Institut Francais du Royaume-Uni. Continuum The Tower Building 370 Lexington Avenue 11 York Road New York, NY London, SE1 7NX 10017-6503 www.continuumbooks.com First published in France, 1981, by Editions de la Difference © Editions du Seuil, 2002, Francis Bacon: Logique de la Sensation This English translation © Continuum 2003 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers. British Library Gataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from The British Library ISBN 0-8264-6647-8 Typeset by BookEns Ltd., Royston, Herts. Printed by MPG Books Ltd., Bodmin, Cornwall Contents Translator's Preface, by Daniel W. Smith vii Preface to the French Edition, by Alain Badiou and Barbara Cassin viii Author's Foreword ix Author's Preface to the English Edition x 1. The Round Area, the Ring 1 The round area and its analogues Distinction between the Figure and the figurative The fact The question of "matters of fact" The three elements of painting: structure, Figure, and contour - Role of the fields 2. -

Volume 50, No. 5 (May 1951)

WHERE THE i CURTAIN FALLS i By Jan Valtin How to Win a Contest How to pamper a husband When a grass-cutting luisl)and lies down on the job, it's a wise wife who hurries Sciditz to tlie iiamniociv. More foli<s (including husbands) like the taste of Schlitz than any other beer. In fact. Schlitz tastes so good to so many peo|)le that it's . The Largest-spUing Beer in America Hear Radio's Brightest Comedy: Mr. timl Mrs. Rounltl Colrnnn star fur Selililz a- "The llnlls of Ivy" every W. dni i-ilay over NBC © 1951, JOS. SCHLITZ BREWING CO., MILWAUKEE, WIS. 5i There's a big difference between walnut, i. walrus —and there is a powerful difference, foo# between gusnline and ^^ETHYL^^ gasoline! There is nothing like "Ethyl" gasoline . for bringing out the top performance of a new cor ... or making an older one feel young again! When you see the familiar yellow-and-black "Ethyl" emblem on a pump, you know you are getting this better gasoline. "Ethyl" antiknock fluid is the famous ingredient that steps up power and performance. Ethyl Corporation, NewYork 17,N.Y. (technical) Other products sold under the "Ethyl" trade-mark: sail caks ; : ; ethylena dichloridd . sodium (metallic) . chlorina (liquid) > : : oil solubis dye : ; t benzene hexachlorido ! !— - vol. M Ml. B Vitalis ilVfc-AeriOlfcare givG5 you LEGION HandsomQr Mair Coiitvnts for 3iuy 19!il The poppy scene on nvir eover lof)Us like so many Main Streets PEDRO THE GAMBLER (fiction) that there'll protiably l)e a goo<i (leal of guess- BY JIM K.TELG.'^.4RD 11 ing as to the actual He never knew what a long chance he look.