Sardinia) from † Easements to Ecosystem Services

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

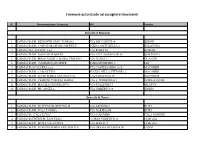

Farmacie Autorizzate Ad Accogliere Tirocinanti

Farmacie autorizzate ad accogliere tirocinanti N° Denominazione Farmacia VIA Località Distretto di Macomer 1 FARMACIA DR. DEMONTIS GIOV. TOMASO VIA DEI CADUTI 14 BIRORI 2 FARMACIA DR. CAPPAI GRAZIANO MICHELE P.ZZA CORTE BELLA 3 BOLOTANA 3 FARMACIA CADEDDU s.a.s. VIA ROMA 56 BORORE 4 FARMACIA DR. BIANCHI ALBERTO VIA VITT. EMANUELE 56 BORTIGALI 5 FARMACIA DR. PIRAS ANGELA MARIA CRISTINA VIA DANTE 1 DUALCHI 6 FARMACIA DR. GAMMINO GIUSEPPE P.ZZA MUNICIPIO 3 LEI 7 FARMACIA SCALARBA s.a.s. VIA CASTELSARDO 12/A MACOMER 8 FARMACIA DR. CABOI LUIGI PIAZZA DELLA VITTORIA 2 MACOMER 9 FARMACIA DR. SECHI MARIA ANTONIETTA VIA SARDEGNA 59 MACOMER 10 FARMACIA DR. CHERCHI TOMASO MARIA VIA E. D'ARBOREA 1 NORAGUGUME 11 FARMACIA DR. MASALA GIANFRANCO VIA STAZIONE 13 SILANUS 12 FARMACIA DR. PIU ANGELA VIA UMBERTO 88 SINDIA Distretto di Nuoro 1 FARMACIA DR. BUFFONI GIUSEPPINA M. VIA ASPRONI 9 BITTI 2 FARMACIA DR. TOLA TONINA VIA GARIBALDI BITTI 3 FARMACIA "CALA LUNA" VIA COLOMBO CALA GONONE 4 FARMACIA EREDI DR. FANCELLO CORSO UMBERTO 13 DORGALI 5 FARMACIA DR. MURA VALENTINA VIA MANNU 1 DORGALI 6 FARMACIA DR. BUFFONI MARIA ANTONIETTA VIA GRAZIA DELEDDA 80 FONNI 7 FARMACIA DR. MEREU CATERINA VIA ROMA 230 GAVOI 8 FARMACIA DR. SEDDA GIANFRANCA LARGO DANTE ALIGHIERI 1 LODINE 9 FARMACIA DR. PIRAS PIETRO VIA G.M.ANGIOJ LULA 10 FARMACIA DR. FARINA FRANCESCO SAVERIO VIA VITT. EMANUELE MAMOIADA 11 FARMACIA SAN FRANCESCO di Luciana Canargiu VIA SENATORE MONNI 2 NUORO 12 FARMACIA DADDI SNC di FRANCESCO DADDI e C. PIAZZA VENETO 3 NUORO 13 FARMACIA DR. -

Allevamento Del Suino, Produzione E Conservazione Dei Salumi

Dipartimento per le produzioni zootecniche Servizio produzioni zootecniche Corso teorico-pratico Allevamento del suino, produzione e conservazione dei salumi Attività di formazione rivolta ai gestori di agriturismi, fattorie didattiche e allevatori della Gallura Programma delle lezioni e calendario degli incontri Sportello Unico Territoriale dell’Alta Ogliastra Via N. Bixio n. 2, Tortolì - Tel. 0782 623084, fax 0782 628033 Data SUT Sede corso Argomento 13-ott-11 Alta Ogliastra Arzana Presentazione Corso Situazione regionale della filiera suinicola Tipologia e sistemi di allevamento dei suini 18-ott-11 Alta Ogliastra Arzana Le razze Gestione dell'allevamento Organizzazione delle varie fasi 20-ott-11 Alta Ogliastra Arzana Gestione sanitaria: Principali malattie Biosicurezza in allevamento 25-ott-11 Alta Ogliastra Arzana Alimentazione: Gli alimenti e le sostanze nutritive Principi di razionamento 27-ott-11 Alta Ogliastra Arzana Lezione pratica Foresta Burgos. Il suino di razza sarda: storia, attualità e prospettive; visita allevamento all'aperto dell'AGRIS. Eventuale visita guidata ad altro/i allevamento/i. 3-nov-11 Alta Ogliastra Arzana Macellazione, qualità delle carni e tagli 8-nov-11 Alta Ogliastra Arzana Classificazione dei salumi. Materie prime per la produzione dei salumi: caratteristiche fisiche, chimiche e microbiologiche; Additivi, aromi e starter 10-nov-11 Alta Ogliastra Arzana Lezione pratica sulla trasformazione e lavorazione dei salumi 15-nov-11 Alta Ogliastra Arzana La macellazione familiare e in agriturismo, La trasformazione artigianale: Iter autorizzativo e caratteristiche dei locali Procedure autorizzative per l'esportazione delle carni suine al di fuori della regione 17-nov-11 Alta Ogliastra Arzana La multifunzionalità dell'azienda agricola 22-nov-11 Alta Ogliastra Arzana Valutazione dei salumi: Analisi sensoriale Principali difetti Sportello Unico Territoriale della Barbagia Via De Gasperi, Gavoi - Tel. -

The Triassic and Jurassic Sedimentary Cycles in Central Sardinia

Geological Field Trips Società Geologica Italiana 2016 Vol. 8 (1.1) ISPRA Istituto Superiore per la Protezione e la Ricerca Ambientale SERVIZIO GEOLOGICO D’ITALIA Organo Cartografico dello Stato (legge N°68 del 2-2-1960) Dipartimento Difesa del Suolo ISSN: 2038-4947 The Triassic and Jurassic sedimentary cycles in Central Sardinia: stratigraphy, depositional environment and relationship between tectonics and sedimentation 85° Congresso Nazionale della Società Geologica Italiana - Sassari, 2008 DOI: 10.3301/GFT.2016.01 The Triassic and Jurassic sedimentary cycles in Central Sardinia: stratigraphy, depositional environment and relationship between tectonics and sedimentation L. G. Costamagna - S. Barca GFT - Geological Field Trips geological fieldtrips2016-8(1.1) Periodico semestrale del Servizio Geologico d'Italia - ISPRA e della Società Geologica Italiana Geol.F.Trips, Vol.8 No.1.1 (2016), 78 pp., 54 figs. (DOI 10.3301/GFT.2016.01) The Triassic and Jurassic sedimentary cycles in Central Sardinia: stratigraphy, depositional environment and relationship between tectonics and sedimentation 85° Congresso Nazionale della Società Geologica Italiana, Sassari 6-8 settembre 2010 Luca G. Costamagna*, Sebastiano Barca** * Dipartimento di Scienze Chimiche e Geologiche, Via Trentino, 51 - 09127, Cagliari (Italy) ** Via P. Sarpi, 18 - 09131, Cagliari (Italy) Corresponding Author e-mail address: [email protected] Responsible Director Claudio Campobasso (ISPRA-Roma) Editorial Board Editor in Chief Gloria Ciarapica (SGI-Perugia) M. Balini, G. Barrocu, C. Bartolini, 2 Editorial Responsible D. Bernoulli, F. Calamita, B. Capaccioni, Maria Letizia Pampaloni (ISPRA-Roma) W. Cavazza, F.L. Chiocci, R. Compagnoni, D. Cosentino, Technical Editor S. Critelli, G.V. Dal Piaz, C. D'Ambrogi, Mauro Roma (ISPRA-Roma) P. -

Posti Disponibili Collaboratori Scolastici

Ministero dell’Istruzione, dell’Università e della Ricerca UFFICIO SCOLASTICO REGIONALE DELLA SARDEGNA Ambito Territoriale Scolastico di Cagliari POSTI DISPONIBILI PER NOMINE A TEMPO DETERMINATO ANNO SCOLASTICO 2019/2020 PROFILO DI COLLABORATORE SCOLASTICO ORGANICO DI DIRITTO ELENCO DELLE SEDI POSTI DISPONIBILI CENTRO TERRITORIALE DISTRETTO 018……………………….. 2 CENTRO TERRITORIALE DISTRETTO 022……………………… 4 CENTRO TERRITORIALE DISTRETTO 023……………………… 5 CENTRO TERRITORIALE DISTRETTO 024………………………… 2 CENTRO TERRITORIALE DISTRETTO 019………………………… 1 CENTRO TERRITORIALE MURAVERA……………………………… 3 I.C. “BENEDETTO CROCE” PULA……………………………………. 1 I.C. VILLAMAR………………………………………………………… 1 I.C.S. "C.COLOMBO" CAGLIARI…………………………………….. 5 IC GONNOSFANADIGA………………………………………………… 1 IC SAN GAVINO MONREALE…………………………………………. 1 IC VILLASOR……………………………………………………………. 1 IC GUASILA…………………………………………………………….. 1 IC D’ARBOREA IGLESIAS…………………………………………….. 1 IC SAN GIOVANNI SUERGIU………………………………………….. 1 I.C. MONSERRATO…………………………………………………….. 1 I.C. "S. CATERINA " CAGLIARI……………………………………….. 2 I.C.G. “FILIBERTO FARCI” SEUI……………………………………. 1 I.I.S. “AZUNI” CAGLIARI……………………………………………. 11 I.T. AGRARIO "DUCA DEGLI ABRUZZI" ELMAS…………………. 4 I.IS MARCONI LUSSU SAN GAVINO………………………………….. 1 I.I.S. “P. LEVI” QUARTU S. ELENA…………………………………… 1 I.I.S. BECCARIA CARBONIA………………………………………… 1 I.I.S. "G. BROTZU" QUARTU S.E………………………………………. 1 I.I.S. "BUCCARI-MARCONI" CAGLIARI ………………………….. 3 SC. SEC. I GRADO ASSEMINI……………………………………. 2 SC.SEC. I GRADO “ALFIERI - CONSERVATORIO CAGLIARI…….. 2 LICEO CL. "DETTORI" CAGLIARI…………………………………… 1 I.M. “E. D’ARBOREA” CAGLIARI…………………………………….. 1 I.P.S.S. “PERTINI” CAGLIARI………………………………………… 1 IPSAR "A. GRAMSCI" MONSERRATO……………………………… 3 IPSIA "A.MEUCCI" CAGLIARI………………………………………. 3 LIC. ARTISTICO "FOISO FOIS" CAGLIARI…………………………. 2 I.T.E. “MARTINI” CAGLIARI…………………………………………. 3 I.T.I. “SCANO” CAGLIARI…………………………………………….. 2 ITCG ZAPPA ISILI………………………………………………………. 2 CONV. NAZ. “VITTORIO EMANUELE” CAGLIARI……………….... 26 ORGANICO DI FATTO ELENCO DELLE SEDI POSTI DISPONIBILI POSTI INTERI D.D. -

Graduatoria Definitiva

Unione dei Comuni Valle del Pardu e dei Tacchi OGLIASTRA MERIDIONALE Cardedu-Gairo-Jerzu-Osini-Perdasdefogu-Tertenia-Ulassai-Ussassai Inserimento socio-lavorativo di soggetti professionalizzati – annualità 2018 Ufficio di Piano GRADUATORIA DEFINITIVA n. Nome Data nascita Residenza Titolo studio Tot 1 Loru Enrica S. Gavino 21/05/1988 Jerzu Laurea specialistia Economia e Commercio 28,50 2 Usai Serenella Lanusei 25/08/1982 Ulassai Laurea Specialistica Scienza dell'amministrazione 24,50 3 Pittalis Giada Lanusei 25/11/1988 Gairo Laurea triennale Amministrazione 23,50 4 Chillotti Marta Lanusei 09/12/1992 Jerzu Laurea magistrale Biologia 23,00 Laurea triennale Mediazione Linguistica e 5 Krautsova Antanina Minsk 20/01/1986 Gairo specialistica in Comunicazione internazionale 23,00 6 Congera Luisa Lanusei 07/04/1979 Ulassai Laurea magistrale Giurisprudenza 23,00 7 Locci Michela Lanusei 22/01/1986 Tertenia Laurea specialistica in Architettura 21,50 8 Deidda Francesca Lanusei 02/08/1991 Ulassai Laurea triennale e magistrale in Scienze geologiche 21,00 9 Deidda Laura Lanusei 2/9/1990 Perdas Laurea magistrale ingegneria civile 21,00 10 Piroddi Luisa Cagliari 01/04/1989 Ulassai Laurea triennale Scienze Politiche 21,00 11 Garau Cesare Lanusei 08/10/1984 Jerzu Laurea specialistica Ingegneria civile 19,50 12 Cannas Marilena Lanusei 15/05/1984 Osini Laurea triennale scienze tecniche erboristiche 19,00 13 Demurtas Roberta Lanusei 19/04/1989 Ulassai Laurea triennale Scienze Turismo 17,50 14 Pavoletti Luca Livorno 26/8/1984 Ussassai Laurea triennale Tecnico -

Elenco Corse

Centro Interuniversitario Regione Autonoma della Sardegna Provincia dell’Ogliastra Ricerche economiche e mobilità PROVINCIA DELL’OGLIASTRA ELENCO CORSE PROGETTO DEFINITIVO Centro Interuniversitario Regione Autonoma della Sardegna Provincia dell’Ogliastra Ricerche economiche e mobilità UNIVERSITÁ DEGLI STUDI DI CAGLIARI CIREM CENTRO INTERUNIVERSITARIO RICERCHE ECONOMICHE E MOBILITÁ Responsabile Scientifico Prof. Ing. Paolo Fadda Coordinatore Tecnico/Operativo Dott. Ing. Gianfranco Fancello Gruppo di lavoro Ing. Diego Corona Ing. Giovanni Durzu Ing. Paolo Zedda Centro Interuniversitario Regione Autonoma della Sardegna Provincia dell’Ogliastra Ricerche economiche e mobilità SCHEMA DEI CORRIDOI ORARIO CORSE CORSE ‐ OGLIASTRA ‐ ANDATA RITORNO CORRIDOIO "GENNA e CRESIA" CORRIDOIO "GENNA e CRESIA" Partenza Arrivo Nome Linee Nome Corsa Km Origine Destinazione Tipologia Veicolo Partenza Arrivo Nome Linee Nome Corsa Km Origine Destinazione Tipologia Veicolo 06:15 07:25 LINEA ROSSA 3630 C1 ‐ fer 40,151 JERZU ARBATAX BUS_15_POSTI A 17:40 18:50 LINEA ROSSA 3630 C1 ‐ fer 40,151 ARBATAX JERZU BUS_15_POSTI R 06:50 08:00 LINEA ROSSA 3630 C ‐ scol 43,012 OSINI NUOVO TORTOLI' STAZIONE FDS BUS_55_POSTI A 13:40 14:50 LINEA ROSSA 3630 C ‐ scol 43,012 TORTOLI' STAZIONE FDS OSINI NUOVO BUS_55_POSTI R 07:00 07:45 LINEA ROSSA 3511 C2 ‐ scol 28,062 LANUSEI PIAZZA V. EMANUELE1 JERZU BUS_55_POSTI A 13:42 14:27 LINEA ROSSA 3511 C2 ‐ scol 28,062 JERZU LANUSEI PIAZZA V. EMANUELE1 BUS_55_POSTI R 07:15 08:00 LINEA ROSSA 3511 C1 ‐ scol 28,062 JERZU LANUSEI PIAZZA V. EMANUELE1 BUS_55_POSTI A 13:42 14:27 LINEA ROSSA 3511 C1 ‐ scol 28,062 LANUSEI PIAZZA V. EMANUELE1 JERZU BUS_55_POSTI R 07:30 07:58 LINEA ROSSA 3 C ‐ scol 18,316 BARI SARDO LANUSEI PIAZZA V. -

N.001-2019 Istituz SUAPE Presso Unione Comuni D'ogliastra

COMUNE DI CARDEDU PROVINCIA DI NUORO DELIBERAZIONE DEL CONSIGLIO COMUNALE n. 1 del 24/01/2019 COPIA Oggetto: Istituzione dello Sportello Unico per le Attività Produttive e per l'Attività Edilizia SUAPE Associato Ogliastra 2, presso lUnione Comuni d'Ogliastra. Approvazione schema di convenzione (allegato A). Approvazione schema di regolamento (allegato B). L’anno DUEMILADICIANNOVE il giorno ventiquattro del mese di gennaio alle ore 18,05 presso la sala delle adunanze, si è riunito il Consiglio Comunale,convocato con avvisi spediti a termini di legge, in sessione ordinaria ed in prima convocazione. Risultano presenti/assenti i seguenti consiglieri: PIRAS MATTEO PRESENTE MOLINARO ARMANDO PRESENTE COCCO SABRINA PRESENTE PILIA PATRIK PRESENTE CUCCA PIER LUIGI PRESENTE PISU MARIA SOFIA ASSENTE CUCCA SIMONE PRESENTE PODDA MARCO PRESENTE DEMURTAS MARCO PRESENTE SCATTU FEDERICO PRESENTE LOTTO GIOVANNI PRESENTE VACCA MARCELLO PRESENTE MARCEDDU MIRCO ASSENTE Quindi n. 11 (undici) presenti su n. 13 (tredici) componenti assegnati, n. 2 (due) assenti. il Signor Matteo Piras, nella sua qualità di Sindaco, assume la presidenza e, assistito dal Segretario Comunale Dott.ssa Giovannina Busia, sottopone all'esame del Consiglio la proposta di deliberazione di cui all'oggetto, di seguito riportata: IL CONSIGLIO COMUNALE PREMESSO che: • i Comuni di Arzana, Bari Sardo, Cardedu, Elini, Ilbono, Lanusei e Loceri, con rispettive deliberazioni consiliari, si sono costituiti in Unione ai sensi dell’art. 32 del T.U.E.L. 267/2000 e dell’articolo 3 della ex Legge Regionale 12/2005 - oggi sostituita dalla Legge Regionale 2/2016 - denominandola “ Unione Comuni D’Ogliastra ” ed approvando con i medesimi atti lo Statuto e l’atto costitutivo dell’Unione; • con deliberazione del Consiglio comunale n. -

Tutti Assieme

REGIONE AUTONOMA DELLA SARDEGNA ENTE FORESTE DELLA SARDEGNA Corso concorso selettivo di formazione per il reclutamento di n. 2 dipendenti a tempo indeterminato con laurea in Economia e Commercio, Categoria Quadri, livello retributivo I, amministrativo-contabile (CODICE 4) PUNTEGGI RELATIVI ALLA PROVA SCRITTA DEL 26 OTTOBRE 2006 POS. COGNOME NOME DATA LUOGO DI NASCITA VOTO 1 MEI FABRIZIO 19/02/1973 CARBONIA 25,8 2 BUSIA SONIA 24/08/1975 SASSARI 25,695 3 COCCO MASSIMO 21/06/1971 CAGLIARI 25,1 4 SORU VALERIA 17/12/1966 TERRALBA 24,48 5 CHESSA GIUSEPPINA 10/08/1965 ULASSAI 23,925 6 ATZORI ROBERTA 28/12/1973 CAGLIARI 23,885 7 DESSI' MARIA ELENA 02/03/1974 SORGONO 23,74 8 ARRIZZA FABIO 01/10/1974 ALGHERO 23,37 9 CHIRRI MARIA GIOVANNA 22/08/1965 SASSARI 22,855 10 LAI DANIELA 17/08/1975 CAGLIARI 22,67 11 PANI LORENA 27/04/1967 TERRALBA 22,67 12 ZACCHINO MARIO 15/11/1968 KOELN (GERMANIA) 22,485 13 VIRDIS MARIA FRANCESCA 21/05/1968 CAGLIARI 22,485 14 CASTI CRISTINA 07/10/1975 CAGLIARI 22,3 15 PIGA GIAMPAOLO 28/11/1970 ARMUNGIA 22,3 16 PANI STEFANIA 09/02/1972 CAGLIARI 22,195 17 SCALAS MARINA 14/11/1970 SERRAMANNA 22,195 18 COCCO MARCELLINA 04/12/1971 CAGLIARI 21,825 19 ARESU DENNIS 18/02/1979 HANNOVER 21,785 20 LUSSO STEFANO 30/01/1971 CAGLIARI 21,785 21 MULAS SERAFINO 07/03/1966 NUORO 21,785 22 PUDDU ARMANDA 20/10/1979 QUARTU SANT'ELENA 21,68 23 ORRU' AGOSTINO 27/06/1975 CAGLIARI 21,68 24 BOI ANDREA 27/04/1970 LANUSEI 21,64 25 SCATTU MASSIMILANO 16/07/1980 GAIRO 21,6 26 PELLEGRINI MICHELA 02/11/1970 CAGLIARI 21,125 27 MANCA MAURO 12/01/1973 CAGLIARI -

Autorizzazione Societa GLE Sport A.S.D. Per

PROVINCIA DI NUORO SETTORE INFRASTRUTTURE ZONA OMOGENEA OGLIASTRA SERVIZIO AGRICOLTURA, MANUTENZIONI E TUTELA DEL TERRITORIO DETERMINAZIONE N° 617 DEL 14/06/2019 OGGETTO: Autorizzazione societa GLE Sport A.S.D. per lo svolgimento di una competizione amatoriale e dilettantistica denominata " 8° Rally di Sardegna Bike " indetta per i giorni 16 _ 17 _ 18 _ 19 _ 20 _ 21 Giugno 2019 _ internazionale di Rally _ Raid di Mountain Bike a Tappe. IL RESPONSABILE DEL SERVIZIO VISTI: - l’art.65, comma 2, lett.B) della L.R. 9/2007 di trasferimento alla Provincia delle competenze relative al rilascio delle autorizzazioni in materia di competizioni sportive su strada; - la nota prot. 275 del 30 gennaio 2008 dell’Assessorato Regionale dei Lavori Pubblici, in base alla quale i provvedimenti autorizzativi per lo svolgimento di manifestazioni sportive su strada sono demandati alle Amministrazioni Provinciali competenti per territorio ai sensi della citata L.R. N.9/2006; - l’istanza assunta al protocollo della Provincia di Nuoro Zona Omogenea dell’Ogliastra al n. 2217 del 15/05/2019 della Società Sportiva G.L.E. Sport A.S.D., con sede in Cagliari in via Farina n° 11, a firma del suo Presidente, Sig. Gian Domenico Nieddu, per ottenere l’autorizzazione allo svolgimento di una manifestazione/gara amatoriale/dilettantistica denominata “8° Rally di Sardegna Bike” – internazionale di Rally-Raid di Mountain Bike a tappe da tenersi nei territori dei cantieri dell’Ente Forestas ricadenti nei Comuni di Arzana, Baunei, Desulo, Gairo, Orgosolo, Seui, Talana, Triei, Urzulei, Ussassai e Villagrande Strisaili nei giorni 16 – 17 – 18 – 19 – 20 – 21 Giugno 2019 . -

Official Journal C 3 of the European Union

Official Journal C 3 of the European Union Volume 62 English edition Information and Notices 7 January 2019 Contents IV Notices NOTICES FROM EUROPEAN UNION INSTITUTIONS, BODIES, OFFICES AND AGENCIES European Commission 2019/C 3/01 Euro exchange rates .............................................................................................................. 1 NOTICES FROM MEMBER STATES 2019/C 3/02 Notice inviting proposals for the transfer of an extraction area for hydrocarbon extraction ................ 2 2019/C 3/03 Communication from the Minister for Economic Affairs and Climate Policy of the Kingdom of the Netherlands pursuant to Article 3(2) of Directive 94/22/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council on the conditions for granting and using authorisations for the prospection, exploration and production of hydrocarbons ................................................................................................... 4 V Announcements PROCEDURES RELATING TO THE IMPLEMENTATION OF COMPETITION POLICY European Commission 2019/C 3/04 Prior notification of a concentration (Case M.9148 — Univar/Nexeo) — Candidate case for simplified procedure (1) ........................................................................................................................ 6 EN (1) Text with EEA relevance. OTHER ACTS European Commission 2019/C 3/05 Publication of the amended single document following the approval of a minor amendment pursuant to the second subparagraph of Article 53(2) of Regulation (EU) No 1151/2012 ............................. -

The Military Representation in the Local Media

JOU0010.1177/1464884917700914JournalismEsu and Maddanu 700914research-article2017 Research Essay Journalism 1 –19 Military pollution in no © The Author(s) 2017 Reprints and permissions: war zone: The military sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884917700914DOI: 10.1177/1464884917700914 representation in the journals.sagepub.com/home/jou local media Aide Esu University of Cagliari, Italy Simone Maddanu University of Cagliari, Italy Abstract This article analyses the local press’ representation of an experimental military activity located in Sardinia (Italy). We seek to assess the changes of the portrait of the military over a 57-year period, looking at the relevant narratives that have occurred in the local press. The authors’ perspective scrutinises the local print media as a key medium for understanding representations of the military and its activities. The adoption of frame analysis and the study of the frame effects highlight two main historical storylines. In the early stages of the military base, the military was portrayed as an agent of change, a frame defined as modernity versus tradition. A gradual decline followed in the wake of growing concerns related to the after-effects of experimental military activities, and the military came to be perceived as a threat to local community, military personnel and the environment. Keywords Ethnographic content analysis, local press, military bases, risk, social movements Corresponding author: Simone Maddanu, Department of Social Sciences and Institutions, University of Cagliari, Via Fra Ignazio 78, 09123 Cagliari, Italy. Email: [email protected] 2 Journalism Introduction In 1956, the largest Italian military range and rocket launching site was built in Sardinia and transformed a few years later into an Inter-service Test and Training Range (PISQ1), evolving into one of the most important experimental military areas and training centres in Europe. -

RELAZIONE ELENCO NOMINATIVI CENSIMENTO LAUNEDDAS Febbraio

ASSESSORADU DE SU TUR ISMU , ARTESANIA E CUMMÈRTZIU ASSESSORATO DEL TURISMO , ARTIGIANATO E COMMERCIO PROMOZIONE E VALORIZZAZIONE DELLA LAUNEDDAS Censimento suonatori e costruttori di launeddas L’ antico strumento tradizionale, anima de lla musica che si produce nell'i sola, appartenente solo ed esclusivamente al patrimonio culturale della Sardegna, con un'origine tramandata da millenni, è da considerarsi come un motore fortemente identitario per lo sviluppo turistico, simbolo millenario conosciuto e apprezzato in tutto il mondo, che merita di divenire patrimonio dell’umanità con il riconoscimento dell'Unesco. Con deliberazione n. 53/42 del 20.12.2013 la Giunta Regionale avente ad oggetto “Pro mozione e valorizzazione delle launeddas e istituzione dell’albo dei costruttori e suonatori dell’antico strumento musicale e artigianale della Sardegna”, ha previsto una serie di azioni mirate alla tutela e alla divulgazione delle launeddas, utile volano, di forte impronta culturale e tradizionale, per lo sviluppo turistico ed economico dell’isola. Alcune iniziative sostenute dall’Assessorato del Turismo , Artigianato e Commercio , accompagnate dalle launeddas, hanno avuto risonanza internazionale, come ad esempio “La musique, la culture, les traditions d’une île dans la Méditerranée”, l’evento rappresentato nel mese di maggio 2014 nella sede dell’Unesco di Parigi o il “Culture Festival in London” tenutosi a Londra nel mese di novembre dello stesso anno. A br eve sarà ufficialmente presentato il libro “Launeddas. La voce delle canne nel vento”, un Progetto fortemente voluto dall’Assessorato Regionale, che raccoglie la storia dello strumento, ne evidenzia la completezza e le complessità, ne illustra, inoltre, co n un ampio corredo fotografico storico e inedito anche la bellezza e il suo spazio nell’arte.