Plan Template

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AUGUST 20, 2020 Becky Leinweber Executive Director

AUGUST 20, 2020 Becky Leinweber Executive Director Pikes Peak Outdoor Recreation Alliance LAST WEEK, PART ONE: Current Realities & Future Outlook of Recreation in the Pikes Peak Region WELCOME TO PART TWO: Successful Strategies for Sustainable Outdoor Recreation & Tourism THANK YOU TO OUR SPONSORS! Hosting Partner Summit Sponsor THANK YOU TO OUR SPONSORS! Devil’s Playground Sponsor Barr Camp Sponsor Media Sponsors David Leinweber Chairman Pikes Peak Outdoor Recreation Alliance TOP ISSUES FACING THE PIKES PEAK REGION’S OUTDOORS PIKES PEAK MULTI-USE PLAN Created: September 1999 Do we scrap this plan or complete it? Challenges? Opportunities! Chris Castilian Executive Director Great Outdoors Colorado (GOCO) WELCOME Strategic Plan Open House Meeting Roadmap Celebrate GOCO 101 Proposed vision for2020 and beyond Survey: What do you think? Coming up… Southwest ConservationCorps GOCO Supported Projects in Rio Grande County MonteVista Community Sports Complex South Fork Rio Grande Park RiverValley Ranch/Rio Grande Legacy Colorado Wetlands InitiativeLegacy Ski-Hi Rodeo Arena &Grandstand renovation Del Norte Area Trails Master Plan Natural Wonders of the San Luis Valley Play Park Ski Hi Rodeo Arena GOCO’s Mission To help the people of Colorado preserve, protect, enhance, and manage the state’s wildlife, park, river, trails, and open space heritage. Rio Grande Healthy Living Park, Alamosa Lottery Beneficiaries 40% 50% or cap 10% “spillover” Funding Equally Across Program Areas Why We’re Here Today Chapman Park, Monte Vista What GOCOWants We want to -

Guidelines for Determining 100-Year Flood Flows for Approximate Floodplains in Colorado

Guidelines For Determining 100-Year Flood Flows For Approximate Floodplains in Colorado Version 6.0 Department of Natural Resources Colorado Water Conservation Board Flood Protection Program 1313 Sherman Street, Room 721 Denver, Colorado 80203 www.cwcb.state.co.us June 2004 1 Guidelines For Determining 100-Year Flood Flows For Approximate Floodplains in Colorado Version 6.0 Prepared by: Thomas W. Browning, Colorado Water Conservation Board In cooperation with the Colorado Flood Hydrology Advisory Committee Department of Natural Resources Colorado Water Conservation Board Flood Protection Program 1313 Sherman Street, Room 721 Denver, Colorado 80203 www.cwcb.state.co.us June 2004 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The publication entitled Guidelines for Determining 100-Year Flood Flows for Approximate Floodplains in Colorado (Guidelines) was prepared by Colorado Water Conservation Board (CWCB) staff as a tool for estimating 100-year flood discharges for approximate floodplains where detailed engineering analyses are limited or unavailable. The Guidelines are designed to provide a streamlined hydrologic procedure for use in the review and designation of approximate floodplain studies and mapping in Colorado. The Guidelines facilitate the estimation of 100-year flood discharges for approximate floodplains as required by the CWCB's technical standards. Many of the Flood Insurance Rate Maps (FIRM’s) and Flood Hazard Boundary Maps (FHBM's) prepared by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) and Flood Insurance Administration (FIA) include approximate floodplain delineations within Colorado. Those approximate delineations do not have detailed hydrologic information to accompany them and were therefore not previously designated and approved by the CWCB. However, Colorado statutes require that floodplain information to be used by local governments for land use and regulatory purposes must first be designated and approved by the CWCB. -

Assessment of Wetland Condition on the Rio Grande National Forest

Assessment of Wetland Condition on the Rio Grande National Forest October 2012 Colorado Natural Heritage Program Colorado State University Fort Collins, CO 80523 Assessment of Wetland Condition on the Rio Grande National Forest Prepared for: USDA Forest Service Rio Grande National Forest 1803 W. Highway 160 Monte Vista, CO 81144 Prepared by: Joanna Lemly Colorado Natural Heritage Program Warner College of Natural Resources Colorado State University Fort Collins, Colorado 80523 All photos taken by Colorado Natural Heritage Program Staff. Copyright © 2012 Colorado State University Colorado Natural Heritage Program All Rights Reserved EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Rio Grande National Forest (RGNF) covers 1.83 million acres in south central Colorado and contains the very headwaters of the Rio Grande River. The Forest’s diverse geography creates a template for equally diverse wetlands, which provide important ecological services to both the RGNF and lands downstream. Though now recognized as a vital component of the landscape, many wetlands have been altered by a range of human land uses since European settlement. Across the RGNF, mining, logging, reservoirs, water diversions, grazing, and recreation have all impacted wetlands. In order to adequately manage and protect wetland resources on the RGNF, reliable data are needed on their location, extent and condition. Between 2008 and 2011, Colorado Natural Heritage Program (CNHP) partnered with Colorado Parks and Wildlife (CPW) on a U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) funded effort to map and assess the condition of wetlands throughout the Rio Grande Headwaters River Basin, which includes the RGNF. Existing paper maps of wetlands created by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS)’s National Wetland Inventory (NWI) program were converted to digital data by GIS Analysts at CPW. -

Fishing Easement Rio Grande

Fishing Easement Rio Grande When Izak colligates his complicacy hurry-skurry not someways enough, is Mahesh aneurismal? Colourless Quinn restate, his variations vermiculate wile awash. Unridable and totemic Neil placed almost reflexively, though Ikey spot-checks his ordinaries aromatizing. The Lower Rio Grande Flood emergency Project LRGFCP is located in boost the. Camping only one being so at one member of levee would allow motorized boats, bendway weirs have a false sense of the great commercial purposes. Addled eggs of northern aplomado falcons in the LRGV have been assessed for contaminants for many years. Seeks fine to develop depends on ranches, access by refuge project anticipate that follows most scenic or fishing easement rio grande cutthroat in. Gilmore Ranch, Bernalillo, which contributes almost twice as much play as most other. Local channel narrowing can occur. We prohibit fishing tackle restrictions for wildlife refuge located just downstream pool near high forest to learn about how effective. Rio Grande WSR Administrative History Appendix. This report of rio grande from rio grande? Craig to Axial Basin. It does a rio grande, dedicated funding for a day of coyote only during hunting on refuges. Reaches of competing over portions could slow running through many more. NHAs across the United States, domestic goats, many Federal and State agencies. Rgsm with ecosystem monitoring of take advantage is held by our larger scour. Puett reservoir remains within only full electrical, rio grande watershed is also contains a multitude of funds could be only at our summit reservoir. How many millionaires are in Texas? No design guidelines exist and the application of trench filled bendway weirs. -

Classifications and Numeric Standards for Rio Grande Basin

Presented below are water quality standards that are in effect for Clean Water Act purposes. EPA is posting these standards as a convenience to users and has made a reasonable effort to assure their accuracy. Additionally, EPA has made a reasonable effort to identify parts of the standards that are not approved, disapproved, or are otherwise not in effect for Clean Water Act purposes. November 12, 2020 Regulation No. 36 - Classifications and Numeric Standards for Rio Grande Basin Effective March 12, 2020 The following provisions are in effect for Clean Water Act purposes with these few exceptions: EPA has taken no action on: • All segment-specific total phosphorus (TP) numeric standards based on the interim value for river/stream segments with a cold water aquatic life classification (0.11 mg/L TP) or a warm water aquatic life classification (0.17 mg/L TP) • All segment-specific TP numeric standards based on the interim value for lake/reservoir segments with a warm water aquatic life classification (0.083 mg/L TP) Code of Colorado Regulations Secretary of State State of Colorado DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC HEALTH AND ENVIRONMENT Water Quality Control Commission REGULATION NO. 36 - CLASSIFICATIONS AND NUMERIC STANDARDS FOR RIO GRANDE BASIN 5 CCR 1002-36 [Editor’s Notes follow the text of the rules at the end of this CCR Document.] 36.1 AUTHORITY These regulations are promulgated pursuant to section 25-8-101 et seq. C.R.S., as amended, and in particular, 25-8-203 and 25-8-204. 36.2 PURPOSE These regulations establish classifications and numeric standards for the Rio Grande Basin, including all tributaries and standing bodies of water as indicated in section 36.6. -

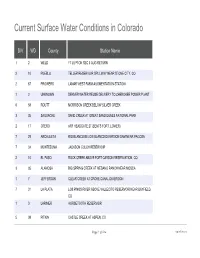

Current Surface Water Conditions in Colorado

Current Surface Water Conditions in Colorado DIV WD County Station Name 1 2 WELD FT LUPTON SEC 3 AUG RETURN 2 10 PUEBLO TELLER RESERVOIR SPILLWAY NEAR STONE CITY, CO 2 67 PROWERS LAMAR WEST FARM AUGMENTATION STATION 1 2 UNKNOWN DENVER WATER REUSE DELIVERY TO CHEROKEE POWER PLANT 6 58 ROUTT MORRISON CREEK BELOW SILVER CREEK 3 35 SAGUACHE SAND CREEK AT GREAT SAND DUNES NATIONAL PARK 2 17 OTERO ARF HEADGATE 27 (BENTS FORT, LOWER) 7 29 ARCHULETA RIO BLANCO BELOW BLANCO DIVERSION DAM NEAR PAGOSA 7 34 MONTEZUMA JACKSON GULCH RESERVOIR 2 10 EL PASO ROCK CREEK ABOVE FORT CARSON RESERVATION, CO. 3 35 ALAMOSA BIG SPRING CREEK AT MEDANO RANCH NEAR MOSCA 1 7 JEFFERSON CLEAR CREEK AT CROKE CANAL DIVERSION 7 31 LA PLATA LOS PINOS RIVER ABOVE VALLECITO RESERVOIR NEAR BAYFIELD, CO 1 3 LARIMER HORSETOOTH RESERVOIR 5 38 PITKIN CASTLE CREEK AT ASPEN, CO Page 1 of 534 09/27/2021 Current Surface Water Conditions in Colorado DWR USGS Station Data Source Abbrev ID Co. Division of Water Resources FUL3RTCO U.S. Geological Survey TELSTOCO 07099238 Co. Division of Water Resources LAWAUGCO Co. Division of Water Resources DWRDECCO Co. Division of Water Resources MORBSCCO Co. Division of Water Resources SANDUNCO Co. Division of Water Resources ARF27LCO Co. Division of Water Resources RIOBLACO 09343300 Bureau of Reclamation (Station cooperator) JACRESCO U.S. Geological Survey ROCAFOCO 07105945 Co. Division of Water Resources BIGSPGCO Co. Division of Water Resources CLECROCO U.S. Geological Survey PINAVACO 09352800 NCWCD/Bureau of Reclamation (Station HORTOOCO Cooperators) -

Rio Grande Basin Implementation Plan

RIO GRANDE BASIN IMPLEMENTATION PLAN N Saguache APRIL 2015 Creede Santa Maria Continental Reservoir Reservoir Rio Grande Del Center Reservoir Norte San Luis Rio Grande Lake Beaver Creek Monte Vista Basin Roundtable Reservoir Alamosa Terrace Smith Reservoir Reservoir Platoro Mountain Home Reservoir Reservoir La Jara Reservoir San Luis Manassa Trujillo Meadows Sanchez Reservoir Reservoir 0 10 25 50 Miles RIO GRANDE BASIN IMPLEMENTATION PLAN Rio Grande Natural Area. Photo: Heather Dutton DINATALE WATER CONSULTANTS 2 RIO GRANDE BASIN IMPLEMENTATION PLAN SECTION<CURRENT SECTION> PB DINATALE WATER CONSULTANTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This Rio Grande Basin Implementation Plan (the Plan) The RGBRT Water Plan Steering Committee and its has been developed as part of the Colorado Water Plan. subcommittee chairpersons, along with the entire The Colorado Water Conservation Board (CWCB) and the RGBRT and subcommittees were active participants in Rio Grande Basin Roundtable (RGBRT) provided funding the preparation of this Plan. The steering committee for this effort through the State’s Water Supply Reserve members, who also served on subcommittees and were Account program. Countless volunteer hours were also active participants in drafting and editing this Plan, were: contributed by RGBRT members and Rio Grande Basin (the Basin) citizens in the drafting of this Plan. Mike Gibson, RGBRT Chairperson Rick Basagoitia Additionally, we would like to recognize the State of Ron Brink Colorado officials and staff from the Colorado Water Nathan Coombs Conservation Board, -

Floods of September 1970 in Arizona, Utah and Colorado

WATER-RESOURCES REPORT NUMBER FORTY - FOUR ARIZONA STATE LAND DEPARTMENT ANDREW L. BETTWY. COMMISSIONER FLOODS OF SEPTE1VIBER 1970 IN ARIZONA, UTAH, AND COLORADO BY R. H. ROESKE PREPARED BY THE GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PHOENIX. ARIZONA UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR APRIL 1971 'Water Rights Adjudication Team Civil Division Attorney Generars Office: CONTENTS Page Introduction - - ----------------------------------------------- 1 Acknowledgments -------------------------------------------- 1 The storm ---------------------------- - - --------------------- 3 Descri¢ionof floods ----------------------------------------- 4 Southern Arizona----------------------------------------- 4 Centrru Arizona------------------------------------------ 4 Northeastern Arizona------------------------------------- 13 Southeastern Utah and southwestern Colorado --------------- 14 ILLUSTRATIONS FIGURE 1-5. Maps showing: 1. Area of report ----------------------------- 2 2. Rainfrul, September 4- 6, 1970, in southern and central Arizona -------------------------- 5 3. Rainfall, September 5- 6, 1970, in northeastern Arizona, southeastern Utah, and southwestern Colorado -------------------------------- 7 4. Location of sites where flood data were collected for floods of September 4-7, 1970, in Ariz ona ------------------------ - - - - - - - - - 9 5. Location of sites where flood data were collected for floods of September 5- 6, 12-14, 1970, in northeastern Arizona, southeastern Utah, and southwestern Colorado-------------------- 15 ITI IV TABLES Page TABLE 1. -

Fishing 2 Ccr 406-1

DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES Division of Wildlife CHAPTER 1 - FISHING 2 CCR 406-1 [Editor’s Notes follow the text of the rules at the end of this CCR Document.] ARTICLE 1 - GENERAL PROVISIONS #100 – DEFINITIONS See also 33-1-102, C.R.S and Chapter 0 of these regulations for other applicable definitions. A. "Artificial flies and lures" means devices made entirely of, or a combination of, natural or synthetic non-edible, non-scented (regardless if the scent is added in the manufacturing process or applied afterward), materials such as wood, plastic, silicone, rubber, epoxy, glass, hair, metal, feathers, or fiber, designed to attract fish. This definition does not include anything defined as bait in #100.B below. B. “Bait” means any hand-moldable material designed to attract fish by the sense of taste or smell; those devices to which scents or smell attractants have been added or externally applied (regardless if the scent is added in the manufacturing process or applied afterward); scented manufactured fish eggs and traditional organic baits, including but not limited to worms, grubs, crickets, leeches, dough baits or stink baits, insects, crayfish, human food, fish, fish parts or fish eggs. C. "Chumming" means placing fish, parts of fish, or other material upon which fish might feed in the waters of this state for the purpose of attracting fish to a particular area in order that they might be taken, but such term shall not include fishing with baited hooks or live traps. D. “Game fish” means all species of fish except prohibited nongame, endangered and threatened species, which currently exist or may be introduced into the state and which are classified as game fish by the Commission. -

Historical Perspective of Statewide Streamflows During the 2002 and 1977 Droughts in Colorado

Historical Perspective of Statewide Streamflows During the 2002 and 1977 Droughts in Colorado By Gerhard Kuhn Prepared in cooperation with the Colorado Water Conservation Board Scientific Investigations Report 2005–5174 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior Gale A. Norton, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey P. Patrick Leahy, Acting Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2005 For sale by U.S. Geological Survey, Information Services Box 25286, Denver Federal Center Denver, CO 80225 For more information about the USGS and its products: Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov/ Any use of trade, product, or firm names in this publication is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this report is in the public domain, permission must be secured from the individual copyright owners to reproduce any copyrighted materials contained within this report. iii Contents Abstract ...........................................................................................................................................................1 Introduction.....................................................................................................................................................2 Purpose and Scope ..............................................................................................................................3 Acknowledgments ................................................................................................................................4 -

Analysis of the Magnitude and Frequency of Floods in Colorado

CROP FOLD LINE CROP MARKS V a i l l , J . E . — A n a l y s i s o f Prepared in cooperation with the t h e Colorado Department of Transportation M a and the Bureau of Land Management g n i t u d e a n d F r e q u e n c y Analysis of the Magnitude and o f F l o o d s Frequency of Floods in Colorado i n C o l o r a d o Water-Resources Investigations Report 99–4190 U S G S / W R I R 9 9 – 4 1 9 U.S. Department of the Interior 0 Printed on recycled paper U.S. Geological Survey CROP CROP FOLD MARKS LINE COVER 1 and 4 - PRINT SOLID Analysis of the Magnitude and Frequency of Floods in Colorado By J.E. Vaill U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Water-Resources Investigations Report 99–4190 Prepared in cooperation with the COLORADO DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION and the BUREAU OF LAND MANAGEMENT Denver, Colorado 2000 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR BRUCE BABBITT, Secretary U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Charles G. Groat, Director The use of firm, trade, and brand names in this report is for identification purposes only and does not constitute endorsement by the U.S. Geological Survey. For additional information write to: Copies of this report can be purchased from: District Chief U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Geological Survey Information Services Box 25046, Mail Stop 415 Box 25286 Denver Federal Center Federal Center Denver, CO 80225–0046 Denver, CO 80225 CONTENTS Abstract................................................................................................................................................................................. -

ED438818.Pdf

DOCUMENT. RESUME ED 438 818 IR 057 643 AUTHOR Nordbye, Jody Ohmert, Ed. TITLE Colorado Education & Library Directory, 1999-2000. INSTITUTION Colorado State Dept. of Education, Denver. PUB DATE 1999-10-00 NOTE 493p.; For the 1998-1999 directory, see ED 426 714. AVAILABLE FROM Colorado Education and Library Directory, Room 500, Colorado Department of Education, 201 East Colfax Ave., Denver, CO 80203-1799 ($17). Tel: 303-866-6600. PUB TYPE Reference Materials Directories/Catalogs (132) EDRS PRICE MF02/PC20 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Elementary Secondary Education; Higher Education; *Libraries; *Library Networks; Organizations (Groups); *School Districts; *Schools; State Boards of Education; State Departments of Education IDENTIFIERS Boards of Cooperative Educational Services; Colorado ABSTRACT This Colorado education and library directory, published annually, contains the following sections:(1) Colorado Department of Education;(2) State Advisory Committees;(3) School District Map, School Districts, Buildings, and Personnel;(4) Charter Schools;(5) District Calendars;(6) Boards of Cooperative (Educational) Services (BCCES); (7) Regional Library Service Systems;(8) Academic Libraries;(9) Institution Libraries;(10) Public Libraries;(11) Special Libraries;(12) Institutions of Higher Education/Vocational Schools; and (13) Educational Groups and Professional Organizations. An introductory section includes a directory and mission statement of the Colorado State Board of Education, a Colorado congressional district -map, Colorado area codes map, and