Sous Les Pavés, La Plage | Ibraaz

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mark Wallinger: State Britain: Tate Britain, London, 15 January – 27 August 2007

Mark Wallinger: State Britain: Tate Britain, London, 15 January – 27 August 2007 Yesterday an extraordinary work of political-conceptual-appropriation-installation art went on view at Tate Britain. There’ll be those who say it isn’t art – and this time they may even have a point. It’s a punch in the face, and a bunch of questions. I’m not sure if I, or the Tate, or the artist, know entirely what the work is up to. But a chronology will help. June 2001: Brian Haw, a former merchant seaman and cabinet-maker, begins his pavement vigil in Parliament Square. Initially in opposition to sanctions on Iraq, the focus of his protest shifts to the “war on terror” and then the Iraq war. Its emphasis is on the killing of children. Over the next five years, his line of placards – with many additions from the public - becomes an installation 40 metres long. April 2005: Parliament passes the Serious Organised Crime and Police Act. Section 132 removes the right to unauthorised demonstration within one kilometre of Parliament Square. This embraces Whitehall, Westminster Abbey, the Home Office, New Scotland Yard and the London Eye (though Trafalgar Square is exempted). As it happens, the perimeter of the exclusion zone passes cleanly through both Buckingham Palace and Tate Britain. May 2006: The Metropolitan Police serve notice on Brian Haw to remove his display. The artist Mark Wallinger, best known for Ecce Homo (a statue of Jesus placed on the empty fourth plinth in Trafalgar Square), is invited by Tate Britain to propose an exhibition for its long central gallery. -

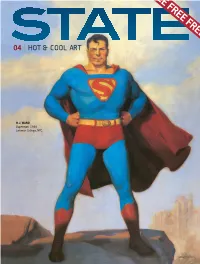

State 04 Layout 1

EE FREE FREE 04 | HOT & COOL ART H.J. WARD Superman 1940 Lehman College, NYC. Pulpit in Empty Chapel Oil on canvas Bed under Window Oil on canvas ‘How potent are these as ‘This new work is terrific in images of enclosed the emptiness of psychic secrecies!’ space in today's society, and MEL GOODING of the fragility of the sacred. Special works.’ DONALD KUSPIT stephen newton Represented in Northern England Represented in Southern England Abbey Walk Gallery Baker-Mamonova Galleries 8 Abbey Walk 45-53 Norman Road Grimsby St. Leonards-on-Sea www.newton-art.com Lincolnshire DN311NB East Sussex TN38 2QE >> IN THIS ISSUE COVER .%'/&)00+%00)6= IMAGE ,%713:)( H.J. Ward Superman 1940 Lehman College, NYC. ;IPSSOJSV[EVHXSWIIMRK]SYEXSYVRI[ 3 The first ever painting of Superman is the work of Hugh TVIQMWIW1EWSRW=EVH0SRHSR7; Joseph Ward (1909-1945) who died tragically young at 35 from cancer. He spent a lot of his time creating the sensational covers for pulp crime magazines, usually young 'YVVIRXP]WLS[MRK0IW*ERXSQIW[MXL women suggestively half-dressed, as well as early comic CONJURING THE ELEMENTS STREET STYLE REDUX [SVOF]%FSYHME%JIH^M,YKLIW0ISRGI book heroes like The Lone Ranger and Green Hornet. His main Public Art Triumphs Pin-point Paul Jones employer was Trojan Publications, but around 1940, Ward 08| 10 | 6ETLEIP%KFSHNIPSY&ERHSQE4EE.SI was commissioned to paint the first ever full length portrait of Superman to coincide with a radio show. He was paid ,EQEHSY1EMKE $100. The painting hung in the chief’s office at DC comics until mysteriously disappearing in 1957 (see editorial). -

UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title No such thing as society : : art and the crisis of the European welfare state Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4mz626hs Author Lookofsky, Sarah Elsie Publication Date 2009 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO No Such Thing as Society: Art and the Crisis of the European Welfare State A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Art History, Theory and Criticism by Sarah Elsie Lookofsky Committee in charge: Professor Norman Bryson, Co-Chair Professor Lesley Stern, Co-Chair Professor Marcel Hénaff Professor Grant Kester Professor Barbara Kruger 2009 Copyright Sarah Elsie Lookofsky, 2009 All rights reserved. The Dissertation of Sarah Elsie Lookofsky is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: Co-Chair Co-Chair University of California, San Diego 2009 iii Dedication For my favorite boys: Daniel, David and Shannon iv Table of Contents Signature Page…….....................................................................................................iii Dedication.....................................................................................................................iv Table of Contents..........................................................................................................v Vita...............................................................................................................................vii -

Britain After Empire

Britain After Empire Constructing a Post-War Political-Cultural Project P. W. Preston Britain After Empire This page intentionally left blank Britain After Empire Constructing a Post-War Political-Cultural Project P. W. Preston Professor of Political Sociology, University of Birmingham, UK © P. W. Preston 2014 Softcover reprint of the hardcover 1st edition 2014 978-1-137-02382-7 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. No portion of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, Saffron House, 6–10 Kirby Street, London EC1N 8TS. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. The author has asserted his right to be identified as the author of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. First published 2014 by PALGRAVE MACMILLAN Palgrave Macmillan in the UK is an imprint of Macmillan Publishers Limited, registered in England, company number 785998, of Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS. Palgrave Macmillan in the US is a division of St Martin’s Press LLC, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010. Palgrave Macmillan is the global academic imprint of the above companies and has companies and representatives throughout the world. Palgrave® and Macmillan® are registered trademarks in the United States, the United Kingdom, Europe and other countries. -

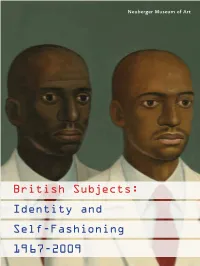

British Subjects: Identity and Self-Fashioning 19 67-2009 for Full Functionality Please Open Using Acrobat 8

Neuberger Museum of Art British Subjects: Identity and Self-Fashioning 19 67-2009 For full functionality please open using Acrobat 8. 4 Curator’s Foreword To view the complete caption for an illustration please roll your mouse over the figure or plate number. 5 Director’s Preface Louise Yelin 6 Visualizing British Subjects Mary Kelly 29 An Interview with Amelia Jones Susan Bright 37 The British Self: Photography and Self-Representation 49 List of Plates 80 Exhibition Checklist Copyright Neuberger Museum of Art 2009 Neuberger Museum of Art All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission in writing from the publishers. Director’s Foreword Curator’s Preface British Subjects: Identity and Self-Fashioning 1967–2009 is the result of a novel collaboration British Subjects: Identity and Self-Fashioning 1967–2009 began several years ago as a study of across traditional disciplinary and institutional boundaries at Purchase College. The exhibition contemporary British autobiography. As a scholar of British and postcolonial literature, curator, Louise Yelin, is Interim Dean of the School of Humanities and Professor of Literature. I intended to explore the ways that the life writing of Britons—construing “Briton” and Her recent work addresses the ways that life writing and self-portraiture register subjective “British” very broadly—has registered changes in Britain since the Second World War. responses to changes in Britain since the Second World War. She brought extraordinary critical Influenced by recent work that expands the boundaries of what is considered under the insight and boundless energy to this project, and I thank her on behalf of a staff and audience rubric of autobiography and by interdisciplinary exchanges made possible by my institutional that have been enlightened and inspired. -

4. Contemporary Art in London

저작자표시-비영리-변경금지 2.0 대한민국 이용자는 아래의 조건을 따르는 경우에 한하여 자유롭게 l 이 저작물을 복제, 배포, 전송, 전시, 공연 및 방송할 수 있습니다. 다음과 같은 조건을 따라야 합니다: 저작자표시. 귀하는 원저작자를 표시하여야 합니다. 비영리. 귀하는 이 저작물을 영리 목적으로 이용할 수 없습니다. 변경금지. 귀하는 이 저작물을 개작, 변형 또는 가공할 수 없습니다. l 귀하는, 이 저작물의 재이용이나 배포의 경우, 이 저작물에 적용된 이용허락조건 을 명확하게 나타내어야 합니다. l 저작권자로부터 별도의 허가를 받으면 이러한 조건들은 적용되지 않습니다. 저작권법에 따른 이용자의 권리는 위의 내용에 의하여 영향을 받지 않습니다. 이것은 이용허락규약(Legal Code)을 이해하기 쉽게 요약한 것입니다. Disclaimer 미술경영학석사학위논문 Practice of Commissioning Contemporary Art by Tate and Artangel in London 런던의 테이트와 아트앤젤을 통한 현대미술 커미셔닝 활동에 대한 연구 2014 년 2 월 서울대학교 대학원 미술경영 학과 박 희 진 Abstract The practice of commissioning contemporary art has become much more diverse and complex than traditional patronage system. In the past, the major commissioners were the Church, State, and wealthy individuals. Today, a variety of entities act as commissioners, including art museums, private or public art organizations, foundations, corporations, commercial galleries, and private individuals. These groups have increasingly formed partnerships with each other, collaborating on raising funds for realizing a diverse range of new works. The term, commissioning, also includes this transformation of the nature of the commissioning models, encompassing the process of commissioning within the term. Among many commissioning models, this research focuses on examining the commissioning practiced by Tate and Artangel in London, in an aim to discover the reason behind London's reputation today as one of the major cities of contemporary art throughout the world. -

Columbia University Department of Art History

COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENT OF ART HISTORY AND ARCHAEOLOGY MIRIAM AND IRA D. WALLACH FINE ARTS CENTER FALL 2007 826schermerhorn Zoë Strother returns to from the chairman’s office Columbia University My term as chairman began in January, but a long-standing commit- Zoë Strother returns to ment to deliver the Slade Lectures at Cambridge University found me in Columbia this fall as the first England for the first half of spring term. During that time, my esteemed Riggio Professor of African colleague, and our former department chairman, Professor David Rosand, Art, after serving on the faculty led the department with a sure hand. I am deeply grateful to David for of the University of California, taking on this duty and to Emily Gabor, our Department Administrator, Los Angeles. She will be happily welcomed by faculty and our excellent office staff for helping him so ably. members in the Department Traditionally, the messages from department chairmen that are regular who worked with her when features of our newsletter combine reflection on the past academic year she taught at Columbia and a preview of the year that lies ahead. It is a great pleasure to begin with between 1995 and 2000. She some truly wonderful news. As the 2006–07 academic year was drawing is well known as a teacher and to a close, word arrived of a magnificent gift to the department from scholar of African art and the Mr. and Mrs. Leonard Riggio. The Riggio gift (described on page 3) will art of the African Diaspora, provide funds for two professorships, fellowships for graduate students, with a specialization in art of Central Africa. -

Fourth Plinth: Contemporary Monument Contemporary 5 Dec 2012— 20 Jan 2013 Fourth Plinth: Contemporary Monument Contemporary

5 Dec 2012— 20 Jan 2013 Fourth Plinth: Contemporary Monument 5 Dec 2012— 20 Jan 2013 Fourth Plinth: Contemporary Monument Foreword The Mayor of London's Fourth Plinth has always been a space for experimentation in contemporary art. It is therefore extremely fitting for this exciting exhibition to be opening at the Institute of Contemporary Arts, London – an institution with a like-minded vision that continues to champion radical and pioneering art. This innovative and thought-provoking programme has generated worldwide appeal. It has provided both the impetus and a platform for some of London’s most iconic artworks and has brought out the art critic in everyone – even our taxi drivers. Bringing together all twenty-one proposals for the first time, and exhibiting them in close proximity to Trafalgar Square, this exhibition presents an opportunity to see behind the scenes, not only of the Fourth Plinth but, more broadly, of the processes behind commissioning contemporary art. It has been a truly fascinating experience to view all the maquettes side-by-side in one space, to reflect on thirteen years’ worth of work and ideas, and to think of all the changes that have occurred over this period: changes in artistic practice, the city’s government, the growing heat of public debate surrounding national identity and how we are represented through the objects chosen to adorn our public spaces. The triumph of the Fourth Plinth is that it ignites discussion among those who would not usually find themselves considering the finer points of contemporary art. We very much hope this exhibition will continue to stimulate debate and we encourage you to tell us what you think at: www.london.gov.uk/fourthplinth Justine Simons Head of Culture for the Mayor of London Gregor Muir Executive Director, ICA 2 3 5 Dec 2012— 20 Jan 2013 Fourth Plinth: Contemporary Monument One Thing Leads To Another… Michaela Crimmin Trafalgar Square holds interesting tensions. -

Carlier | Gebauer Press Release Mark Wallinger

carlier | gebauer Press release Mark Wallinger | Mark Wallinger 30.04.- 28.05.2016 Opening: Friday, April 29th, 2016 For his seventh solo exhibition with carlier | gebauer, the Turner Prize winning artist Mark Wallinger will present his new series id Paintings. According to Freud, the id, driven by the pleasure principle, is the source of all psychic energy. Wallinger’s id Paintings (2015) are intuitive and guided by instinct, echoing the primal, impulsive and libidinal characteris - tics of the id. These monumental paintings have grown out of Wallinger’s longstanding self- portrait series, and reference the artist’s own body. Wallinger’s height – or arm span – is the basis of the canvas size, they are exactly this mea - surement in width and double in height. Created by sweeping paint-laden hands across the canvas in active, freeform gestures, the id Paintings bear the evidence of their making and of the artist’s performed encounter with the surface. The perceptible handprints within the paint recall cave paint - ings and signpost a single active participant. The paintings are apprehended at the point of arrest, encouraging forensic examination. Wallinger uses symmetrical bodily gestures, causing the two halves of the canvas to mirror one another. Through this process, reference could be made to the bilateral symmetry of Leonardo da Vinci’s ‘Vitruvian Man’, an ideal representation of the human body and its denotations of proportion in mirror writing. The paintings bear a deliberate visual resemblance to the Rorschach test: in recognizing figures and shapes in the material, the viewer reveals their own desires and predilections, or perhaps tries to interpret those of the artist. -

A Pamphlet for the Serpentine Gallery Manifesto Marathon 2008: 1

MANIFESTO PAMPHLET 18/19.10.2008 A pamphlet for the Serpentine Gallery Manifesto Marathon 2008: 1. The historic avant-gardes of the early 20th century and the neo- avant-gardes in the 1960s and 70s created a time of radical manifestos. 2. We now live in a time that is more atomised and has less cohesive artistic movements. 3. At this moment, there is a reconnection to the manifesto as a document of poetic and political intent. 4. This is a declaration of artistic will and new-found optimism. 5. New modes of publication and production are a means to distribute ideas in the form of texts, documents, and radical pamphlets. 6. This futurological congress presents manifestos for the 21st century. This event is urgent. 1 MANIFESTO PAMPHLET 18/19.10.2008 Gilbert & George (1969) SPONSOR’S FOREWORD In an exciting journey to discover the future of travel and relaunch their brand, Kuoni has partnered with a series of prominent experts from the worlds of contemporary lifestyle, fashion, art, architecture, music and literature. The latest in its ongoing series of collaborations sees Kuoni partner with the Serpentine Gallery, and, from 18 – 19 October, Kuoni is proud to be the headline sponsor of the Serpentine Gallery Manifesto Marathon. Through the sponsorship of the Manifesto Marathon, Kuoni will collect new perspectives on travel and develop these into a ‘new culture of travelling’–a selection of luxury, unique and authentic travel experiences. The Kuoni and Serpentine Gallery relationship is based on a common sense of curiosity and passion for innovation. Moreover, the concept of the Manifesto Marathon closely mirrors the Kuoni Getaway Council –an ever-evolving group of prolific experts and innovative thinkers from different fields, industries and countries– which was set up as a platform for exchanging ideas and finding new ways to innovate in travel. -

An Interview with Mark Wallinger

An Interview with Mark Wallinger Downloaded from http://direct.mit.edu/octo/article-pdf/doi/10.1162/octo.2008.123.1.185/1754526/octo.2008.123.1.185.pdf by guest on 24 September 2021 YVE-ALAIN BOIS, GUY BRETT, MARGARET IVERSEN, AND JULIAN STALLABRASS The following discussion with the British artist Mark Wallinger, which took place in his London flat on June 3, 2007, essentially focuses on State Britain, his eight-month installation at Tate Britain.1 The excellent press release provided by the museum deserves to be quoted in full: Mark Wallinger has recreated peace campaigner Brian Haw’s Parliament Square protest for a dramatic new installation at Tate Britain. Running along the full length of the Duveen Galleries, State Britain consists of a meticulous reconstruction of over 600 weather-beaten banners, pho- tographs, peace flags and messages from well-wishers that have been amassed by Haw over the past five years. Faithful in every detail, each section of Brian Haw’s peace camp from the makeshift tarpaulin shelter and tea-making area to the profusion of hand-painted placards and teddy bears wearing peace-slogan t-shirts has been painstakingly sourced and replicated for the display. Brian Haw began his protest against the economic sanction in Iraq in June 2001, and has remained opposite the Palace of Westminster ever since. On 23 May 2006, following the passing by Parliament of the “Serious Organised Crime and Police Act” prohibiting unauthorised demonstrations within a one kilometer radius of Parliament Square, the majority of Haw’s protest was removed. Taken literally, the edge of this exclusion zone bisects Tate Britain. -

The Magazine of the Glasgow School of Art Issue 10

Issue 10 The magazine of The Glasgow School of Art FlOW ISSUE 10 Cover Image: There will be no miracles here, installation view at Mount Stuart. Nathan Coley Photo:Kenneth Hunter >BRIEFING Hot 50 We√come Design Week magazine has put the GSA into its HOT 50 honours list of people and Welcome to Issue 10 of Flow. organisations that have made a significant contribution Nathan Coley’s work, pictured on the front of this issue of Flow, makes a bold declaration – There to design. will be no miracles here. However, the word miracle is derived from the Latin word miraculum The magazine describes the GSA as a leader in the meaning ‘something wonderful’ and had we commissioned Nathan to produce a similar piece of field of design education and work for the School, he could have boldly declared There are miracles here – there is ‘something commends the School for wonderful’ here. engaging in ‘socially relevant design rather that just creating We try to share the ‘something wonderful’ that is The Glasgow School of Art in every issue of Flow a product’. and this issue is no different, sharing with you the successes and achievements of our students, SIE Success for Red Button alumni and staff, but also some of the challenges that the School is facing and the creative ways For the fourth year in succession, in which we are addressing them. This issue looks at scholarships and the co-curriculum.Through GSA students have won prizes our responses to these challenges, we are not only building on our tradition of access, but are in the Scottish Institute continuing to produce graduates who are professionally orientated and socially engaged.