The Suez Crisis: a Brief Comint History (U)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE AMERICAN UNIVERSITY in CAIRO School of Humanities And

1 THE AMERICAN UNIVERSITY IN CAIRO School of Humanities and Social Sciences Department of Arab and Islamic Civilizations Islamic Art and Architecture A thesis on the subject of Revival of Mamluk Architecture in the 19th & 20th centuries by Laila Kamal Marei under the supervision of Dr. Bernard O’Kane 2 Dedications and Acknowledgments I would like to dedicate this thesis for my late father; I hope I am making you proud. I am sure you would have enjoyed this field of study as much as I do. I would also like to dedicate this for my mother, whose endless support allowed me to pursue a field of study that I love. Thank you for listening to my complains and proofreads from day one. Thank you for your patience, understanding and endless love. I am forever, indebted to you. I would like to thank my family and friends whose interest in the field and questions pushed me to find out more. Aziz, my brother, thank you for your questions and criticism, they only pushed me to be better at something I love to do. Zeina, we will explore this world of architecture together some day, thank you for listening and asking questions that only pushed me forward I love you. Alya’a and the Friday morning tours, best mornings of my adult life. Iman, thank you for listening to me ranting and complaining when I thought I’d never finish, thank you for pushing me. Salma, with me every step of the way, thank you for encouraging me always. Adham abu-elenin, thank you for your time and photography. -

Empire's H(A)Unting Grounds: Theorising Violence and Resistance in Egypt and Afghanistan

Empire’s h(a)unting grounds: theorising violence and resistance in Egypt and Afghanistan LSE Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/102631/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Manchanda, Nivi and Salem, Sara (2020) Empire’s h(a)unting grounds: theorising violence and resistance in Egypt and Afghanistan. Current Sociology, 68 (2). pp. 241-262. ISSN 1461-7064 10.1177%2F0011392119886866 Reuse Items deposited in LSE Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the LSE Research Online record for the item. [email protected] https://eprints.lse.ac.uk/ Empire’s H(a)unting Grounds: Theorising violence and resistance in Egypt and Afghanistan Nivi Manchanda, Queen Mary University of London Sara Salem, London School of Economics Abstract This article thinks theory otherwise by searching for what is missing, silent and yet highly productive and constitutive of present realities’. Looking at Afghanistan and Egypt, we show how imperial legacies and capitalist futurities are rendered invisible by dominant social theories, and why it matters that we think beyond an empiricist sociology in the Middle East. In Afghanistan, we explore the ways in which portrayals of the country as retrogressive elide the colonial violence that that have ensured the very backwardness that is now considered Afghanistan’s enduring characteristic. -

Suez Canal Development Project: Egypt's Gate to the Future

Economy Suez Canal Development Project: Egypt's Gate to the Future President Abdel Fattah el-Sissi With the Egyptian children around him, when he gave go ahead to implement the East Port Said project On November 27, 2015, President Ab- Egyptians’ will to successfully address del-Fattah el-Sissi inaugurated the initial the challenges of careful planning and phase of the East Port Said project. This speedy implementation of massive in- was part of a strategy initiated by the vestment projects, in spite of the state of digging of the New Suez Canal (NSC), instability and turmoil imposed on the already completed within one year on Middle East and North Africa and the August 6, 2015. This was followed by unrelenting attempts by certain interna- steps to dig out a 9-km-long branch tional and regional powers to destabilize channel East of Port-Said from among Egypt. dozens of projects for the development In a suggestive gesture by President el of the Suez Canal zone. -Sissi, as he was giving a go-ahead to This project is the main pillar of in- launch the new phase of the East Port vestment, on which Egypt pins hopes to Said project, he insisted to have around yield returns to address public budget him on the podium a galaxy of Egypt’s deficit, reduce unemployment and in- children, including siblings of martyrs, crease growth rate. This would positively signifying Egypt’s recognition of the role reflect on the improvement of the stan- of young generations in building its fu- dard of living for various social groups in ture. -

Omar-Ashour-English.Pdf

CENTER ON DEMOCRACY, DEVELOPMENT, AND THE RULE OF LAW STANFORD UNIVERSITY BROOKINGS DOHA CENTER - STANFORD PROJECT ON ARAB TRANSITIONS PAPER SERIES Number 3, November 2012 FROM BAD COP TO GOOD COP: THE CHALLENGE OF SECURITY SECTOR REFORM IN EGYPT OMAR ASHOUR PROGRAM ON ARAB REFORM AND DEMOCRACY, CDDRL FROM BAD COP TO GOOD COP: THE CHALLENGE OF SECURITY SECTOR REFORM IN EGYPT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY gence within the police force of a cadre of reform- ist officers is also encouraging and may help shift Successful democratic transitions hinge on the the balance of power within the Ministry of Interi- establishment of effective civilian control of the or. These officers have established reformist orga- armed forces and internal security institutions. The nizations, such as the General Coalition of Police transformation of these institutions from instru- Officers and Officers But Honorable, and begun to ments of brutal repression and regime protection push for SSR themselves. The prospects for imple- to professional, regulated, national services – secu- menting these civil society and internal initiatives, rity sector reform (SSR) – is at the very center of however, remain uncertain; they focus on admira- this effort. In Egypt, as in other transitioning Arab ble ends but are less clear on the means of imple- states and prior cases of democratization, SSR is mentation. They also have to reckon with strong an acutely political process affected by an array of elements within the Ministry of Interior – “al-Ad- different actors and dynamics. In a contested and ly’s men” (in reference to Mubarak’s longstanding unstable post-revolutionary political sphere, the minister) – who remain firmly opposed to reform. -

Eastern Europe

* *»t« »t<»»t« ************* Eastern Europe INTRODUCTION FTER A PROTRACTED STRUGCLE, Nikita Khrushchev succeeded in July 1957 AL. in securing the removal from top Communist Party and government positions of Vyacheslav Molotov, Lazar Kaganovich, Georgi Malenkov, and Dmitri Shepilov. At the same time two other lesser party leaders, Mikail Pervukhin and Maxim Saburov, were removed from the Party presidium. The decision to remove them was taken at a plenary meeting of the Com- munist Party Central Committee in Moscow June 22-29, 1957. Khrushchev and the 309-member Central Committee accused the deposed leaders, the so- called "anti-Party group," of wanting to lead the Party back to the pattern of leadership and the political line that had prevailed under Josef Stalin. While there were varying interpretations as to which of the contending men and factions represented what policy, it was clear that in this all-important fight for power a new and significant element had been introduced. In his duel with the oldest and most authoritative leaders of the Party, Khrushchev could not muster more than about half of the presidium votes. The powerful support he needed to break the deadlock came from the Soviet army. The backing of Marshal Georgi Zhukov, according to reliable reports, assured Khrushchev's victory. At the same Central Committee meeting, Zhukov was elevated to full membership in the Party presidium. After the June plenum, the influence of Marshal Zhukov and his role in the government of the Soviet Union seemed to increase, and the marshal's pronouncements indicated that he did not underestimate his newly acquired power position. -

Refugee Status Appeals Authority New Zealand

REFUGEE STATUS APPEALS AUTHORITY NEW ZEALAND REFUGEE APPEAL NO 76505 AT AUCKLAND Before: B L Burson (Chairperson) S A Aitchison (Member) Counsel for the Appellant: D Mansouri-Rad Appearing for the Department of Labour: No Appearance Date of Hearing: 3 & 4 May 2010 Date of Decision: 14 June 2010 DECISION [1] This is an appeal against the decision of a refugee status officer of the Refugee Status Branch (RSB) of the Department of Labour (DOL) declining refugee status to the appellant, a national of Iraq. INTRODUCTION [2] The appellant claims to have a well-founded fear of being persecuted in Iraq on account of his former Ba’ath Party membership in the rank of Naseer Mutakadim, and due to his father’s position as Branch Member of the al-Amed Organisation for the Ba’ath Party in City A. He fears persecution at the hands of members of the Mahdi Army – a Shi’a militia group in Iraq, the police who collaborate with them, and the Iraqi Government that is infiltrated by militias. [3] The principal issues to be determined in this appeal are the well- foundedness of the appellant’s fears and whether he can genuinely access meaningful domestic protection. 2 THE APPELLANT’S CASE [4] What follows is a summary of the appellant’s evidence in support of his claim. It will be assessed later in this decision. Background [5] The appellant is a single man in his early-30s. He was born in Suburb A in City A. He is one of three children, the youngest of two boys. -

Country Advice Egypt Egypt – EGY37024 – Treatment of Anglican Christians in Al Minya 2 August 2010

Country Advice Egypt Egypt – EGY37024 – Treatment of Anglican Christians in Al Minya 2 August 2010 1. Please provide detailed information on Al Minya, including its location, its history and its religious background. Please focus on the Christian population of Al Minya and provide information on what Christian denominations are in Al Minya, including the Anglican Church and the United Coptic Church; the main places of Christian worship in Al Minya; and any conflict in Al Minya between Christians and the authorities. 1 Al Minya (also known as El Minya or El Menya) is known as the „Bride of Upper Egypt‟ due to its location on at the border of Upper and Lower Egypt. It is the capital city of the Minya governorate in the Nile River valley of Upper Egypt and is located about 225km south of Cairo to which it is linked by rail. The city has a television station and a university and is a centre for the manufacture of soap, perfume and sugar processing. There is also an ancient town named Menat Khufu in the area which was the ancestral home of the pharaohs of the 4th dynasty. 2 1 „Cities in Egypt‟ (undated), travelguide2egypt.com website http://www.travelguide2egypt.com/c1_cities.php – Accessed 28 July 2010 – Attachment 1. 2 „Travel & Geography: Al-Minya‟ 2010, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica Online, 2 August http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/384682/al-Minya – Accessed 28 July 2010 – Attachment 2; „El Minya‟ (undated), touregypt.net website http://www.touregypt.net/elminyatop.htm – Accessed 26 July 2010 – Page 1 of 18 According to several websites, the Minya governorate is one of the most highly populated governorates of Upper Egypt. -

Title of Thesis: ABSTRACT CLASSIFYING BIAS

ABSTRACT Title of Thesis: CLASSIFYING BIAS IN LARGE MULTILINGUAL CORPORA VIA CROWDSOURCING AND TOPIC MODELING Team BIASES: Brianna Caljean, Katherine Calvert, Ashley Chang, Elliot Frank, Rosana Garay Jáuregui, Geoffrey Palo, Ryan Rinker, Gareth Weakly, Nicolette Wolfrey, William Zhang Thesis Directed By: Dr. David Zajic, Ph.D. Our project extends previous algorithmic approaches to finding bias in large text corpora. We used multilingual topic modeling to examine language-specific bias in the English, Spanish, and Russian versions of Wikipedia. In particular, we placed Spanish articles discussing the Cold War on a Russian-English viewpoint spectrum based on similarity in topic distribution. We then crowdsourced human annotations of Spanish Wikipedia articles for comparison to the topic model. Our hypothesis was that human annotators and topic modeling algorithms would provide correlated results for bias. However, that was not the case. Our annotators indicated that humans were more perceptive of sentiment in article text than topic distribution, which suggests that our classifier provides a different perspective on a text’s bias. CLASSIFYING BIAS IN LARGE MULTILINGUAL CORPORA VIA CROWDSOURCING AND TOPIC MODELING by Team BIASES: Brianna Caljean, Katherine Calvert, Ashley Chang, Elliot Frank, Rosana Garay Jáuregui, Geoffrey Palo, Ryan Rinker, Gareth Weakly, Nicolette Wolfrey, William Zhang Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Gemstone Honors Program, University of Maryland, 2018 Advisory Committee: Dr. David Zajic, Chair Dr. Brian Butler Dr. Marine Carpuat Dr. Melanie Kill Dr. Philip Resnik Mr. Ed Summers © Copyright by Team BIASES: Brianna Caljean, Katherine Calvert, Ashley Chang, Elliot Frank, Rosana Garay Jáuregui, Geoffrey Palo, Ryan Rinker, Gareth Weakly, Nicolette Wolfrey, William Zhang 2018 Acknowledgements We would like to express our sincerest gratitude to our mentor, Dr. -

Suez 1956 24 Planning the Intervention 26 During the Intervention 35 After the Intervention 43 Musketeer Learning 55

Learning from the History of British Interventions in the Middle East 55842_Kettle.indd842_Kettle.indd i 006/09/186/09/18 111:371:37 AAMM 55842_Kettle.indd842_Kettle.indd iiii 006/09/186/09/18 111:371:37 AAMM Learning from the History of British Interventions in the Middle East Louise Kettle 55842_Kettle.indd842_Kettle.indd iiiiii 006/09/186/09/18 111:371:37 AAMM Edinburgh University Press is one of the leading university presses in the UK. We publish academic books and journals in our selected subject areas across the humanities and social sciences, combining cutting-edge scholarship with high editorial and production values to produce academic works of lasting importance. For more information visit our website: edinburghuniversitypress.com © Louise Kettle, 2018 Edinburgh University Press Ltd The Tun – Holyrood Road, 12(2f) Jackson’s Entry, Edinburgh EH8 8PJ Typeset in 11/1 3 Adobe Sabon by IDSUK (DataConnection) Ltd, and printed and bound in Great Britain. A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978 1 4744 3795 0 (hardback) ISBN 978 1 4744 3797 4 (webready PDF) ISBN 978 1 4744 3798 1 (epub) The right of Louise Kettle to be identifi ed as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, and the Copyright and Related Rights Regulations 2003 (SI No. 2498). 55842_Kettle.indd842_Kettle.indd iivv 006/09/186/09/18 111:371:37 AAMM Contents Acknowledgements vii 1. Learning from History 1 Learning from History in Whitehall 3 Politicians Learning from History 8 Learning from the History of Military Interventions 9 How Do We Learn? 13 What is Learning from History? 15 Who Learns from History? 16 The Learning Process 18 Learning from the History of British Interventions in the Middle East 21 2. -

ACLED) - Revised 2Nd Edition Compiled by ACCORD, 11 January 2018

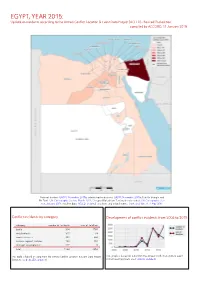

EGYPT, YEAR 2015: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) - Revised 2nd edition compiled by ACCORD, 11 January 2018 National borders: GADM, November 2015b; administrative divisions: GADM, November 2015a; Hala’ib triangle and Bir Tawil: UN Cartographic Section, March 2012; Occupied Palestinian Territory border status: UN Cartographic Sec- tion, January 2004; incident data: ACLED, undated; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 Conflict incidents by category Development of conflict incidents from 2006 to 2015 category number of incidents sum of fatalities battle 314 1765 riots/protests 311 33 remote violence 309 644 violence against civilians 193 404 strategic developments 117 8 total 1244 2854 This table is based on data from the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project This graph is based on data from the Armed Conflict Location & Event (datasets used: ACLED, undated). Data Project (datasets used: ACLED, undated). EGYPT, YEAR 2015: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) - REVISED 2ND EDITION COMPILED BY ACCORD, 11 JANUARY 2018 LOCALIZATION OF CONFLICT INCIDENTS Note: The following list is an overview of the incident data included in the ACLED dataset. More details are available in the actual dataset (date, location data, event type, involved actors, information sources, etc.). In the following list, the names of event locations are taken from ACLED, while the administrative region names are taken from GADM data which serves as the basis for the map above. In Ad Daqahliyah, 18 incidents killing 4 people were reported. The following locations were affected: Al Mansurah, Bani Ebeid, Gamasa, Kom el Nour, Mit Salsil, Sursuq, Talkha. -

Egyptian Natural Gas Industry Development

Egyptian Natural Gas Industry Development By Dr. Hamed Korkor Chairman Assistant Egyptian Natural Gas Holding Company EGAS United Nations – Economic Commission for Europe Working Party on Gas 17th annual Meeting Geneva, Switzerland January 23-24, 2007 Egyptian Natural Gas Industry History EarlyEarly GasGas Discoveries:Discoveries: 19671967 FirstFirst GasGas Production:Production:19751975 NaturalNatural GasGas ShareShare ofof HydrocarbonsHydrocarbons EnergyEnergy ProductionProduction (2005/2006)(2005/2006) Natural Gas Oil 54% 46 % Total = 71 Million Tons 26°00E 28°00E30°00E 32°00E 34°00E MEDITERRANEAN N.E. MED DEEPWATER SEA SHELL W. MEDITERRANEAN WDDM EDDM . BG IEOC 32°00N bp BALTIM N BALTIM NE BALTIM E MED GAS N.ALEX SETHDENISE SET -PLIOI ROSETTA RAS ELBARR TUNA N BARDAWIL . bp IEOC bp BALTIM E BG MED GAS P. FOUAD N.ABU QIR N.IDKU NW HA'PY KAROUS MATRUH GEOGE BALTIM S DEMIATTA PETROBEL RAS EL HEKMA A /QIR/A QIR W MED GAS SHELL TEMSAH ON/OFFSHORE SHELL MANZALAPETROTTEMSAH APACHE EGPC EL WASTANI TAO ABU MADI W CENTURION NIDOCO RESTRICTED SHELL RASKANAYES KAMOSE AREA APACHE Restricted EL QARAA UMBARKA OBAIYED WEST MEDITERRANEAN Area NIDOCO KHALDA BAPETCO APACHE ALEXANDRIA N.ALEX ABU MADI MATRUH EL bp EGPC APACHE bp QANTARA KHEPRI/SETHOS TAREK HAMRA SIDI IEOC KHALDA KRIER ELQANTARA KHALDA KHALDA W.MED ELQANTARA KHALDA APACHE EL MANSOURA N. ALAMEINAKIK MERLON MELIHA NALPETCO KHALDA OFFSET AGIBA APACHE KALABSHA KHALDA/ KHALDA WEST / SALLAM CAIRO KHALDA KHALDA GIZA 0 100 km Up Stream Activities (Agreements) APACHE / KHALDA CENTURION IEOC / PETROBEL -

A Short History of Egypt – to About 1970

A Short History of Egypt – to about 1970 Foreword................................................................................................... 2 Chapter 1. Pre-Dynastic Times : Upper and Lower Egypt: The Unification. .. 3 Chapter 2. Chronology of the First Twelve Dynasties. ............................... 5 Chapter 3. The First and Second Dynasties (Archaic Egypt) ....................... 6 Chapter 4. The Third to the Sixth Dynasties (The Old Kingdom): The "Pyramid Age"..................................................................... 8 Chapter 5. The First Intermediate Period (Seventh to Tenth Dynasties)......10 Chapter 6. The Eleventh and Twelfth Dynasties (The Middle Kingdom).......11 Chapter 7. The Second Intermediate Period (about I780-1561 B.C.): The Hyksos. .............................................................................12 Chapter 8. The "New Kingdom" or "Empire" : Eighteenth to Twentieth Dynasties (c.1567-1085 B.C.)...............................................13 Chapter 9. The Decline of the Empire. ...................................................15 Chapter 10. Persian Rule (525-332 B.C.): Conquest by Alexander the Great. 17 Chapter 11. The Early Ptolemies: Alexandria. ...........................................18 Chapter 12. The Later Ptolemies: The Advent of Rome. .............................20 Chapter 13. Cleopatra...........................................................................21 Chapter 14. Egypt under the Roman, and then Byzantine, Empire: Christianity: The Coptic Church.............................................23