Pennsylvania Railroad Electrification Strategy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RAILROAD COMMUNICATIONS Amtrak

RAILROAD COMMUNICATIONS Amtrak Amtrak Police Department (APD) Frequency Plan Freq Input Chan Use Tone 161.295 R (160.365) A Amtrak Police Dispatch 71.9 161.295 R (160.365) B Amtrak Police Dispatch 100.0 161.295 R (160.365) C Amtrak Police Dispatch 114.8 161.295 R (160.365) D Amtrak Police Dispatch 131.8 161.295 R (160.365) E Amtrak Police Dispatch 156.7 161.295 R (160.365) F Amtrak Police Dispatch 94.8 161.295 R (160.365) G Amtrak Police Dispatch 192.8 161.295 R (160.365) H Amtrak Police Dispatch 107.2 161.205 (simplex) Amtrak Police Car-to-Car Primary 146.2 160.815 (simplex) Amtrak Police Car-to-Car Secondary 146.2 160.830 R (160.215) Amtrak Police CID 123.0 173.375 Amtrak Police On-Train Use 203.5 Amtrak Police Area Repeater Locations Chan Location A Wilmington, DE B Morrisville, PA C Philadelphia, PA D Gap, PA E Paoli, PA H Race Amtrak Police 10-Codes 10-0 Emergency Broadcast 10-21 Call By Telephone 10-1 Receiving Poorly 10-22 Disregard 10-2 Receiving Well 10-24 Alarm 10-3 Priority Service 10-26 Prepare to Copy 10-4 Affirmative 10-33 Does Not Conform to Regulation 10-5 Repeat Message 10-36 Time Check 10-6 Busy 10-41 Begin Tour of Duty 10-7 Out Of Service 10-45 Accident 10-8 Back In Service 10-47 Train Protection 10-10 Vehicle/Person Check 10-48 Vandalism 10-11 Request Additional APD Units 10-49 Passenger/Patron Assist 10-12 Request Supervisor 10-50 Disorderly 10-13 Request Local Jurisdiction Police 10-77 Estimated Time of Arrival 10-14 Request Ambulance or Rescue Squad 10-82 Hostage 10-15 Request Fire Department 10-88 Bomb Threat 10-16 -

Railroad Postcards Collection 1995.229

Railroad postcards collection 1995.229 This finding aid was produced using ArchivesSpace on September 14, 2021. Description is written in: English. Describing Archives: A Content Standard Audiovisual Collections PO Box 3630 Wilmington, Delaware 19807 [email protected] URL: http://www.hagley.org/library Railroad postcards collection 1995.229 Table of Contents Summary Information .................................................................................................................................... 4 Historical Note ............................................................................................................................................... 4 Scope and Content ......................................................................................................................................... 5 Administrative Information ............................................................................................................................ 5 Controlled Access Headings .......................................................................................................................... 6 Collection Inventory ....................................................................................................................................... 6 Railroad stations .......................................................................................................................................... 6 Alabama ................................................................................................................................................... -

Pennvolume1.Pdf

PENNSYLVANIA STATION REDEVELOPMENT PROJECT ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT TABLE OF CONTENTS VOLUME I: ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT Executive Summary ............................................................... 1 ES.1 Introduction ................................................................ 1 ES.2 Purpose and Need for the Proposed Action ......................................... 2 ES.3 Alternatives Considered ....................................................... 2 ES.4 Environmental Impacts ....................................................... 3 ES.4.1 Rail Transportation .................................................... 3 ES.4.2 Vehicular and Pedestrian Traffic .......................................... 3 ES.4.3 Noise .............................................................. 4 ES.4.4 Vibration ........................................................... 4 ES.4.5 Air Quality .......................................................... 4 ES.4.6 Natural Environment ................................................... 4 ES.4.7 Land Use/Socioeconomics ............................................... 4 ES.4.8 Historic and Archeological Resources ...................................... 4 ES.4.9 Environmental Risk Sites ............................................... 5 ES.4.10 Energy/Utilities ...................................................... 5 ES.5 Conclusion Regarding Environmental Impact ...................................... 5 ES.6 Project Documentation Availability .............................................. 5 Chapter 1: Description -

Attachment a Statement of Work RFQ Number: 6100041691 OVERVIEW: the Pennsylvania Department of Transportation (Penndot) Is Respo

Attachment A Statement of Work RFQ Number: 6100041691 OVERVIEW: The Pennsylvania Department of Transportation (PennDOT) is responsible for the operating costs for the Amtrak Keystone and Pennsylvanian passenger rail services. The Keystone Service provides frequent higher speed passenger train service along the Amtrak part owned Keystone Corridor between the Harrisburg Transportation Center in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania and 30th Street Station in Philadelphia. Some trains continue on the Northeast Corridor and terminate at Pennsylvania Station in New York, and the Pennsylvanian runs between New York and Pittsburgh with stops in between. PennDOT aims to increase ridership on these services as increased revenue offsets the state subsidy for the rail services, which is estimated to be $14.9 million in the 2017 Federal fiscal year. In 2012, PennDOT and Amtrak partnered on PA Trips By Train (www.patripsbytrain.com), an initiative spotlighting events and destinations in communities along the service routes. PennDOT is shifting the campaign’s focus from excursion travelers to commuter travel (Keystone) with the goal of gaining more riders. BACKGROUND NEEDED TO COMPLETE WORK PLAN: In 2014, Amtrak conducted surveys of 402 Keystone customers and 400 Pennsylvanian customers. PennDOT is advising interested vendors to obtain the results of those surveys to better understand the project. Information from those surveys, including gender, age, income, and more is available only by executing a Non-Disclosure Agreement (NDA) with Amtrak. Interested contractors must fully complete and sign Attachment E, Amtrak Market Research Data Nondisclosure. The completed hard copy with an original ink signature must be submitted to Amtrak. Interested vendors wishing to have an original returned must submit two signed copies. -

Harrisburg Division

HARRISBURG DIVISION NORTHERN REGION TIMETABLE NUMBER 1 EFFECTIVE SEPTEMBER 19, 2015 COMMITTED TO SAFETY DOUBLE ZEROS ZERO INJURIES ZERO INCIDENTS HARRISBURG DIVISION TIMETABLE TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Timetable General Information..................................................5 a. Train Dispatcher Contact Information…………………….4 b. Station Page........................................................................5 c. Explanation of Characters.................................................5 d. Diesel Unit Groups.............................................................6 e. Main Track Control.............................................................6 f. Division Special Instructions.............................................6 II. Harrisburg Division Station Pages.....................................7-263 III. Harrisburg Division Special Instructions......................265-269 NORFOLK SOUTHERN DIVISION HEADQUARTERS Train Dispatching Office 4600 Deer Path Road Harrisburg, PA 17110 Assistant Superintendent – Microwave 541-2146 Bell 717-541-2146 Dispatch Chief Dispatcher Microwave 541-2158 Bell 717-541-2158 Harrisburg East Dispatcher Microwave 541-2136 Bell 717-541-2136 Harrisburg Terminal Dispatcher Microwave 541-2138 Bell 717-541-2138 Lehigh Line Dispatcher Microwave 541-2139 Bell 717-541-2139 Southern Tier Dispatcher Microwave 541-2144 Bell 717-541-2144 Mainline Dispatcher Microwave 541-2142 Bell 717-541-2142 D&H Dispatcher Microwave 541-2143 Bell 717-541-2143 EMERGENCY 911 HARRISBURG DIVISION TIMETABLE GENERAL INFORMATION A. -

National Register of Historic Places Inventory -- Nomination Form

Form No. 10-300 (Rev. 10-74) UNITED STATES DEPARTMEN ,. JF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS I NAME HISTORIC Grand Central Terminal AND/OR COMMON Grand Central Terminal LOCATION STREETS,NUMBER 71-105 East 42nd Street _NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT New York _ VICINITY OF 18th STATE CODE COUNTY CODE New York New York 36 QCLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _DISTRICT —PUBLIC X2DCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM 2^BUILDING(S) ^PRIVATE _ UNOCCUPIED X.COMMERCIAL _PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE _S!TE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS _ OBJECT _IN PROCESS —YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED X_YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL ^-TRANSPORTATION _NO _ MILITARY —OTHER: OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Pennsylvania Central Transportation Company STREET & NUMBER 466 Lexington Avenue CITY. TOWN STATE New York VICINITY OF New York LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, New York County Hall of Records REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC. STREET& NUMBER 31 Chambers Street CITY, TOWN STATE New York New York REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE New York City Landmarks Commission DATE 1967 —FEDERAL —STATE —COUNTY x_LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS CITY, TOWN STATE New York New Yn-rlf DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE _EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED —UNALTERED ^-ORIGINAL SITE X_GOOD —RUINS X_ALTERED _MOVED DATE- _FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE A complete contemporary description would be lengthy—in the brief: "The terminal has two levels. The upper one of these, 20 ft. -

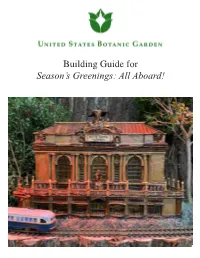

Train Station Models Building Guide 2018

Building Guide for Season’s Greenings: All Aboard! 1 Index of buildings and dioramas Biltmore Depot North Carolina Page 3 Metro-North Cannondale Station Connecticut Page 4 Central Railroad of New Jersey Terminal New Jersey Page 5 Chattanooga Train Shed Tennessee Page 6 Cincinnati Union Terminal Ohio Page 7 Citrus Groves Florida Page 8 Dino Depot -- Page 9 East Glacier Park Station Montana Page 10 Ellicott City Station Maryland Page 11 Gettysburg Lincoln Railroad Station Pennsylvania Page 12 Grain Elevator Minnesota Page 13 Grain Fields Kansas Page 14 Grand Canyon Depot Arizona Page 15 Grand Central Terminal New York Page 16 Kirkwood Missouri Pacific Depot Missouri Page 17 Lahaina Station Hawaii Page 18 Los Angeles Union Station California Page 19 Michigan Central Station Michigan Page 20 North Bennington Depot Vermont Page 21 North Pole Village -- Page 22 Peanut Farms Alabama Page 23 Pennsylvania Station (interior) New York Page 24 Pikes Peak Cog Railway Colorado Page 25 Point of Rocks Station Maryland Page 26 Salt Lake City Union Pacific Depot Utah Page 27 Santa Fe Depot California Page 28 Santa Fe Depot Oklahoma Page 29 Union Station Washington Page 30 Union Station D.C. Page 31 Viaduct Hotel Maryland Page 32 Vicksburg Railroad Barge Mississippi Page 33 2 Biltmore Depot Asheville, North Carolina built 1896 Building Materials Roof: pine bark Facade: bark Door: birch bark, willow, saltcedar Windows: willow, saltcedar Corbels: hollowed log Porch tread: cedar Trim: ash bark, willow, eucalyptus, woody pear fruit, bamboo, reed, hickory nut Lettering: grapevine Chimneys: jequitiba fruit, Kielmeyera fruit, Schima fruit, acorn cap credit: Village Wayside Bar & Grille Wayside Village credit: Designed by Richard Morris Hunt, one of the premier architects in American history, the Biltmore Depot was commissioned by George Washington Vanderbilt III. -

Planning Context

1. Preface This plan serves as the update to Chapter 12, the transportation plan element, of the 2003 Cumberland County Comprehensive Plan. Background information and specific statistics on the modes of transportation in the county can be found in Chapter 11 of the comprehensive plan and in the Harrisburg Area Transportation Study (HATS) Long Range Transportation Plan1. 2. Introduction Cumberland County is home to a variety of transportation resources ranging from interstate highways to sidewalks in local neighborhoods. The transportation infrastructure found in the county supports the national, state and local economies and the high quality of life in our communities, alike. The value of our transportation system warrants the county’s involvement in its planning, design, construction and maintenance. Cumberland County’s transportation planning authority emanates from Article III of the Pennsylvania Municipalities Planning Code (MPC), Act 247 of 1968. The MPC requires county comprehensive plans to include a plan for the “movement of people and goods” that includes all modes of transportation. Under this planning authorization the county’s actual role in planning and implementing improvements for all modes of transportation must be carefully managed. This plan identifies the salient transportation issues and needs facing the county and recommends a series of county-based strategies and action steps aimed at addressing the identified needs and issues. 3. Highways and Bridges Issues and Needs Cumberland County has an extensively developed highway network that provides for local, regional, and national transportation. All roads in the county are owned and maintained by municipalities, the state, or the federal government. The rich hydrologic resources of Cumberland County are spanned by 438 bridges that are over 20’ in length2. -

Lancaster Train Station Master Plan Which Is a Product of the Lancaster County Planning Commission and Funded by Pennsylvania Department of Transportation

Lancaster Train Station Master Plan October 2012 Table of Contents Executive Summary ....................................................................................................................................... i Introduction ................................................................................................................................................... 1 Summary of Current and On-Going Station Improvements ......................................................................... 1 Planning Horizons ......................................................................................................................................... 7 Physical Plant ................................................................................................................................................ 7 Maintenance .......................................................................................................................................... 7 Station Capital Improvements ............................................................................................................... 9 Available Non-Transportation Spaces ................................................................................................ 17 Station Artwork ................................................................................................................................... 19 Historic Preservation .......................................................................................................................... -

Transportation from Baltimore/Washington International Thurgood Marshall Airport (BWI)

Transportation Options to Johns Hopkins Carey Business School’s Harbor East Campus 100 International Drive, Baltimore, MD 21202 This document is not inclusive of all the various forms of transportation options in the Baltimore area. The Carey Business School does not endorse or advise any specific transportation option. The school provides this document only to offer students a list of various transportation options. All information is subject to change and was obtained from the websites of said transportation options. Information within is current and accurate at the time of this documents creation. Links to external or 3rd party websites are for your convenience, check for updated information. TRAVEL FROM LOCAL AIRPORTS There are three airports in close proximity to Baltimore: (1) Baltimore/Washington International Thurgood Marshall Airport (BWI) http://www.bwiairport.com/ 1 (2) Ronald Reagan Washington National Airport (DCA) http://www.metwashairports.com/reagan/reagan.htm (3) Washington Dulles International Airport (IAD) http://www.metwashairports.com/dulles/dulles.htm 3 The information below about how to reach Baltimore is split 2 into sections depending upon the airport where you land. Transportation from Baltimore/Washington International Thurgood Marshall Airport (BWI) 1 CAR RENTAL BWI Airport has a rental car facility. Passengers arriving on flights take the free shuttle from the lower level terminal for a ten-minute ride to the rental facility. Reservations are highly recommended. Cost: The cost of the rental cars will depend upon company and type of vehicle. You can access a list of rental companies at http://www.bwiairport.com/en/travel/ground- transportation/trans/carrental. -

Penn Station Table of Contents

www.PDHcenter.com www.PDHonline.org Penn Station Table of Contents Slide/s Part Description 1N/ATitle 2 N/A Table of Contents 3~88 1 An Absolute Necessity 89~268 2 The Art of Transportation 269~330 3 Eve of Destruction 331~368 4 Lost Cause 369~417 5 View to a Kill 418~457 6 Men’s Room Modern 458~555 7 Greatness to Come Fall From Grace 1 2 Part 1 The Logical Result An Absolute Necessity 3 4 “…The idea of tunneling under the Hudson and East Rivers for an entrance into New York City did not evolve suddenly. It was the logical result of long-studied plans in which Mr. Alexander Johnston Cassatt, the late President of the Company, participated from the beginning, and an entrance into New York City was decided upon only when the Executive Officers and Directors of the Company realized that it had become an absolute necessity…” RE: excerpt from The New York Im- provement and Tunnel Extension of the Pennsylvania Railroad Left: Alexander J. Cassatt (1839-1906), Above: caption: “The empire of the Pennsylvania Railroad, President – Pennsylvania Railroad extending through most of the northeast, but unable to reach Company (1899-1906) 5 Manhattan until 1910” 6 © J.M. Syken 1 www.PDHcenter.com www.PDHonline.org “…After the Company in 1871 leased the United Railroads of New Jersey, which terminate in Jersey City, the Officers of the Railroad looked longingly toward New York City. They wanted a station there, but they were confronted both by the great expense of such an undertaking, as well as the lack of a feasible plan, for at that time the engineering obstacles seemed to be insurmountable. -

Northeast Corridor New York to Philadelphia

Northeast Corridor New York to Philadelphia 1 INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................2 2 A HISTORY..............................................................................................3 3 ROLLING STOCK......................................................................................4 3.1 EMD AEM-7 Electric Locomotive .......................................................................................4 3.2 Amtrak Amfleet Coaches .................................................................................................5 4 SCENARIOS.............................................................................................6 4.1 Go Newark....................................................................................................................6 4.2 New Jersey Trenton .......................................................................................................6 4.3 Spirit or Transportation ..................................................................................................6 4.4 The Big Apple................................................................................................................6 4.5 Early Clocker.................................................................................................................7 4.6 Evening Clocker.............................................................................................................7 4.7 Northeast Regional ........................................................................................................7