“Of Technical Competence, Perceived Autonomy and Relational Expertise”: Understanding Professional Identity Among Nurses Working in a Stroke Unit*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

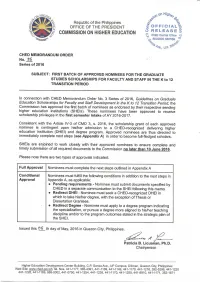

CMO No. 26, Series of 2016

List of Approved SHEI Nominees for Graduate Scholarships in the K to 12 Transition Program BATCH 1 SENDING HIGHER REGION EDUCATION NAME OF FACULTY / PROGRAM TITLE APPLIED FOR PROGRAM DELIVERING HEI (IF REMARKS INSTITUTION (SHEI) STAFF STATUS KNOWN/PROSPECTIVE) 1 ASIACAREER Reyno, Miriam Joy M. Master in Business Administration New Master's Lyceum-Northwestern Redirect Degree, COLLEGE University Redirect DHEI FOUNDATION, INC. 1 COLEGIO DE Baquiran, Brylene Ann Doctor of Philosophy major in New Doctorate Not Stated DAGUPAN R. Educational Management Bautista, Chester Allan Doctor in Information Technology New Doctorate Not Stated Redirect Degree F. Caralos, Edilberto Jr. L. Master in Information Technology New Master's Not Stated Columbino, Marvin B. MS Electronics Engineering New Master's Saint Louis University Dela Cruz, Anna Clarissa Master in Information Technology New Master's Not Stated R. Dela Cruz, Vivian A. Doctor of Philosophy Ongoing Not Stated Doctorate Fernandez, Hajibar Master in Information Technology New Master's Not Stated Jhoneil L. Fortin, Arnaldy D. Doctor in Information Technology New Doctorate Not Stated Gabriel, Jr. Renato J. Master in Communication major New Master's De La Salle University, Taft in Applied Medical Studies Page 1 of 183 Lachica, Evangeline N. Doctor in Information Technology New Doctorate Not Stated Landingin, Mark Joseph Master of Arts in Philosophy New Master's Not Stated D. Macaranas, Jin Benir C. Master of Science in Electrical New Master's Saint Louis University Engineering Navarro, Adessa Bianca Master in Business Administration Ongoing Not Stated G. Master's Ordonez, Jesse Jr. P. Doctor of Philosophy New Doctorate Not Stated Seco, Cristian Rey C. -

Private Higher Education Institutions Faculty-Student Ratio: AY 2017-18

Table 11. Private Higher Education Institutions Faculty-Student Ratio: AY 2017-18 Number of Number of Faculty/ Region Name of Private Higher Education Institution Students Faculty Student Ratio 01 - Ilocos Region The Adelphi College 434 27 1:16 Malasiqui Agno Valley College 565 29 1:19 Asbury College 401 21 1:19 Asiacareer College Foundation 116 16 1:7 Bacarra Medical Center School of Midwifery 24 10 1:2 CICOSAT Colleges 657 41 1:16 Colegio de Dagupan 4,037 72 1:56 Dagupan Colleges Foundation 72 20 1:4 Data Center College of the Philippines of Laoag City 1,280 47 1:27 Divine Word College of Laoag 1,567 91 1:17 Divine Word College of Urdaneta 40 11 1:4 Divine Word College of Vigan 415 49 1:8 The Great Plebeian College 450 42 1:11 Lorma Colleges 2,337 125 1:19 Luna Colleges 1,755 21 1:84 University of Luzon 4,938 180 1:27 Lyceum Northern Luzon 1,271 52 1:24 Mary Help of Christians College Seminary 45 18 1:3 Northern Christian College 541 59 1:9 Northern Luzon Adventist College 480 49 1:10 Northern Philippines College for Maritime, Science and Technology 1,610 47 1:34 Northwestern University 3,332 152 1:22 Osias Educational Foundation 383 15 1:26 Palaris College 271 27 1:10 Page 1 of 65 Number of Number of Faculty/ Region Name of Private Higher Education Institution Students Faculty Student Ratio Panpacific University North Philippines-Urdaneta City 1,842 56 1:33 Pangasinan Merchant Marine Academy 2,356 25 1:94 Perpetual Help College of Pangasinan 642 40 1:16 Polytechnic College of La union 1,101 46 1:24 Philippine College of Science and Technology 1,745 85 1:21 PIMSAT Colleges-Dagupan 1,511 40 1:38 Saint Columban's College 90 11 1:8 Saint Louis College-City of San Fernando 3,385 132 1:26 Saint Mary's College Sta. -

Directory of Higher Education Institutions As of October 23, 2009

Directory of Higher Education Institutions as of October 23, 2009 04001 Abada College Private Non-Sectarian President : Atty. Miguel D. Ansaldo, Jr. Region : IVB - MIMAROPA Address : Marfrancisco, Pinamalayan, Oriental Mindoro 5208 Telephone : (043) 443-13-56 (043)284-41-50 Fax : (043)443-13-56 E-mail : Year Established : April 26, 1950 Website : 06128 ABE International Coll of Business and Economics-Bacolod Private Non-Sectarian School Director : Joretta M. Abraham Region : VI - Western Visayas Address : Luzuriaga Street, Bacolod City, Negros Occidental 6100 Telephone : (034)-432-2484 to 85 Fax : E-mail : [email protected] Year Established : 2001 Website : www.amaes.edu.ph 01122 ABE International College of Business and Accountancy Private Non-Sectarian School Director : Mr. Juanito Mendiola Region : I - Ilocos Region Address : 3rd flr. E&R Bldg. Malolos Crossing, City of Malolos (Capital), Bulacan, Cebu City, Bulacan 2428 Telephone : (032) 234-2421 Fax : (044)662-1018 E-mail : [email protected]/abe_urdaneta_city@hot mail.com Year Established : 2001 Website : http://amaes.educ.ph. 13309 ABE International College of Business and Accountancy-Las Piñas Private Non-Sectarian President : Mr. Amable C. Aguiluz IX Region : NCR - National Capital Region Address : RCS Bldg III, Zapote, Alabang Road, Pamplona, Las Piñas City, City of Las Piñas, Fourth District Telephone : (02) 872-01-83; 872-61-62 Fax : (02) 872-02-20 E-mail : Year Established : 2001 Website : 1 Directory of Higher Education Institutions as of October 23, 2009 13308 ABE International College of Business and Accountancy-Quezon City Private Non-Sectarian President : Mr. Amable C. Aguiluz IX Region : NCR - National Capital Region Address : #878 Rempson Bldg., Aurora Blvd., Cubao, Quezon City, Quezon City, Second District Telephone : (02) 912-95-77; 912-95-78 Fax : (02) 912-95-78 E-mail : Year Established : 2000 Website : 13350 ABE International College of Business and Accountancy-Taft Private Non-Sectarian President : Mr. -

WCCI 50TH Anniversary Celebration Commemorative Program

WCCI 50TH ANNIVERSARY CELEBRATION COMMEMORATIVE PROCEEDINGS 1 Table of Contents Welcome President Toh Swee-Hin . 5 President, Andy Vaughn, Alliant International University . 6 Reflections from the Secretariat . 7 WCCI History . 9 WCCI Conference Locations/Venue/Last 50 Years . 16 Program Overview . 18 Program Highlights . 19 Past Presidents Committee (Jessica Kimmel, Chair) . .. 24 Presidents Council Members . .. 25 Reflections of Early Influential WCCI Eminent Friends Presentations . 26 Executive Board Members . 30 WCCI Board Members and Officers . 31 Institutional Members . 36 Life Members . 37 Business and Marketing Representatives . .. 38 Part II – Tributes to Honor Retirement of Ate Estela as Executive Director Participant Speakers . .. 40 Closing Message – Executive Director, Estela C. Matriano & New Acting President/VP - Emmy Garon . 49 Registered Participants . 50 WCCI Song . 56 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Technical and Production Team Toh Swee-Hin, WCCI President Joyce Pittman, WCCI Board Secretary and Drexel University Semantha Mercanti, Drexel University Carole Caparros, WCCI Secretariat Funding and Supporters Alliant University, San Diego, USA Rush Medical University, Chicago, Illinois, USA Hosts WCCI Board of Directors Others 3 THE VIRTUAL 50th ANNIVERSARY CELEBRATION of the WORLD COUNCIL FOR CURRICULUM & INSTRUCTION (WCCI) NOVEMBER 5, 2020 GMT 2 pm – 4 pm Copyright, WCCI 2021 4 MESSAGE Shalom, Assalamu alaikum, Namaste, Amituofo, Greetings of Peace! On this auspicious commemoration of the 50th Anniversary of WCCI, may I join all members and friends in extending my warmest congratulations for WCCI’s achievements in striving to fulfill its vision and mission as a transnational educational organization for the building of a peaceful, just, inclusive and sustainable world. Fifty years is indeed a long journey to travel and WCCI’s steps in reaching this milestone have drawn on the energies and commitment of a community of educators from diverse regions and countries and multiple fields of learning, teaching, research, and service. -

~ 0 Ill 1Z~ LIBR

1Z ~ LIBR ~ 0 ill e l5..IJ I NF B MATIOl\T Vol. II No.3 Quezon City, Philippine October 1974 In this issue: The Philippine Population-1985 I 2/PSSC Social Science Information October 19741 Editor's notes The conservatives usually cry very the working hours of labourers will be leaders always meddle with it. Their object, loudly against the rapid mechanisation reduced to half. The reduction in the ive is always to serve the interests of their brought about by the use of advanced .working hours will. certainly, have to be party and not the welfare of labourers. types of scientific technology. The fact is effected. keeping in view the demand for that the mechanisation under a capitalistic the commodities and the availability of ******** framework means more misery and labour resources. unemployment to the common people and The proper use of science, under the The aspiration to become rich by ex hence the objection from the conservative collective economic set up will only bring ploiting others is a sort of mental malady. camp. The mechanlsation applied in the forth human welfare. It may well be just In fact,if the eternal hunger of the human I public welfare without hitting the possible that owing to mechanisation no soul does not find the real path leading to I capitalistic framework has to be opposed, one will have to undergo labour for more mental and spiritual wealth, it becomes; because with the double increase in the than five minutes a week. Being not always engaged in the work of depriving others of yield of a machine the requirement of engrossed in the anxiety about grains and human labour will decrease by half clothes,there will be no misuse of their their rights by robbing them of their reo consequently capitalists retrench labourers mental and spiritual resources. -

PASS Acta 16

Crisis in a Global Economy. Re-planning the Journey Pontifical Academy of Social Sciences, Acta 16, 2011 www.pass.va/content/dam/scienzesociali/pdf/acta16/acta16-ramirez.pdf COMMENTARY ON THE PAPERS PERSONAL & FAMILY DECISIONS IN A SCENARIO OF UNCERTAINTY & ETHICS AND ECONOMICS: NEW CONSIDERATIONS FOR ENTREPRENEURS MINA RAMIREZ INTRODUCTION I thank Prof. Msgr. Minnerath for a very lucid paper that elaborates on why the ‘practices of economic development’ which have caused the global economic downturn have been antithetical to the principles of Christian Social Doctrine – human dignity, integrity of creation, common good, social justice, subsidiarity and solidarity. Indeed, the current dominant global eco- nomic system centered on big enterprises and international financial inter- mediaries has unwittingly considered the person merely in ‘economistic’ terms as a commodity or a factor of production that entails cost. The mentality, the worldview of the dominant economic system has cre- ated the condition which led to the global economic crisis. Prof. Vittorio Hösle traced back – since almost 500 years ago to the present – the philo- sophical orientation that has fostered an absolutely individualistic mental- ity thus shaping a worldview which culminated in the present neo-liberal- istic mentality. Cited by Prof. Hösle were the three ‘radical moral innova- tors’ of the social question: Niccolò Machiavelli (1469-1527), extreme indi- vidualism in the realm of politics, Bernard de Mandeville (1670-1733), absolute individualism in the field of economics, and Robert Malthus (1766-1834) in the area of demography. An understanding of Adam Smith’s view of the economy taken out of context – ‘that the economy is partly a self-regulating system’ (‘It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker, that we expect our COMMENTARY ON THE PAPERS BY H.E. -

Three Decades of Peace Education in the Philippines: Stories of Hope and Challenges Copyright © 2017 All Rights Reserved

INSIDE FRONT COVER BLANK PAGE Three Decades of Peace Education in the Philippines: Stories of Hope and Challenges Copyright © 2017 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced without per- mission in writing from the publishers and the authors except by a reviewer or researcher who wishes to quote brief passages in connection with a review or research for inclusion in any other publication. Published by the Center for Peace Education, Miriam College, Katipunan Ave., Quezon City, Philippines, and the World Council for Curriculum and Instruction, Philippines Chapter. Printed by Cover & Pages Publishing, Inc., Manila, Philippines. ISBN: 978-971-0177-12-7 iv Three Decades of Peace Education in the Philippines: Stories of Hope and Challenges Editors: Toh Swee-Hin • Virginia Cawagas • Jasmin N. Galace Assistant Editor: Anna Kristina M. Dinglasan Publishers: Center for Peace Education, Miriam College & World Council for Curriculum and Instruction, Philippines Chapter v 6 Three Decades of Peace Education in the Philippines: Stories of Hope and Challenges CONTENTS Preface .........................................................................................................ix Introduction ................................................................................................. 1 Section I: Visions Crystallized, Seeds Planted Journeying in Solidarity: Educating for a Culture of Peace from Mindanao to Manila and Beyond by Toh Swee-Hin ................... 15 Peace Education: Reflections of a Mindanao Educator by Ofelia L. -

An Annotated Guide to Philippine Serials the Cornell University Southeast Asia Program

AN ANNOTATED GUIDE TO PHILIPPINE SERIALS THE CORNELL UNIVERSITY SOUTHEAST ASIA PROGRAM The Southeast Asia Program was organized at Cornell University in _the Department of Far Eastern Studies in 1950. It is a teaching and research program of interdisciplinary studies in the humanities, social sciences, and some natural sciences. It deals with Southeast Asia as a region, and with the individual countries of the area: Brunei, Burma, Indonesia, the Khmer Republic, Laos, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam. The activities of the Program are carried on both at Cornell and in Southeast Asia. They include an undergraduate and graduate curriculum at Cornell which provides instruction by specialists in Southeast Asian cultural history and present-day affairs and offers intensive training in each of the major languages of the area. The Pro9ram sponsors group research projects on Thailand, on Indonesia, on the Philippines, and on linguistic studies of the languages of the area. At the same time, individual staff and students of the Program have done field research in every Southeast Asian country. A list of publications relating to Southeast Asia which may be obtained on prepaid order directly from the Program is given at end end of this volume. Information on Program staff, fellowships, requirements for degrees, and current course offerings will be found in an Announcement of the DepaPtment of Asian Studies, obtainable from the Director, Southeast Asia Program, 120 Uris Hall, Cornell University, Ithaca, New York 14853. ii -

With a Compendium of Recollections and Tribute Pieces from Bancom Alumni and Friends

The ebook version of this book may be downloaded at www.xBancom.com This Bancom book project was made possible by the generous support of mr. manuel V. Pangilinan. The book launching was sponsored by smart infinity copyright © 2013 by sixto K. roxas Bancom memoirsby sixto K. roxas With a Compendium of Recollections and Tribute Pieces from Bancom Alumni and Friends Edited by eduardo a. Yotoko Published by PLDT-smart Foundation, inc and Bancom alumni, inc. (BaLi) contents Foreword by Evelyn R. Singson 5 Foreword by Francis G. Estrada 7 Preface 9 Prologue: Bancom and the Philippine financial markets 13 chapter 1 Bancom at its 10th year 24 chapter 2 BTco and cBTc, Bliss and Barcelon 28 chapter 3 ripe for investment banking 34 chapter 4 Founding eDF 41 chapter 5 organizing PDcP 44 chapter 6 childhood, ateneo and social action 48 chapter 7 my development as an economist 55 chapter 8 Practicing economics at central Bank and PnB 59 chapter 9 corporate finance at Filoil 63 chapter 10 economic planning under macapagal 71 chapter 11 shaping the development vision 76 chapter 12 entering the money market 84 chapter 13 creating the Treasury Bill market 88 chapter 14 advising on external debt management 90 chapter 15 Forming a virtual merchant bank 103 chapter 16 Functional merger with rcBc 108 chapter 17 asean merchant banking network 112 chapter 18 some key asian central bankers 117 chapter 19 asia’s star economic planners 122 chapter 20 my american express interlude 126 chapter 21 radical reorganization and BiHL 136 chapter 22 Dewey Dee and the end of Bancom 141 chapter 23 The total development company components 143 chapter 24 a changed life-world 156 chapter 25 The sustainable development movement 167 chapter 26 The Bancom university of experience 174 chapter 27 summing up the legacy 186 Photo Folio 198 compendium of recollections and Tribute Pieces from Bancom alumni and Friends 205 4 Bancom memoirs Bancom was absorbed by union Bank in 1981. -

School Codes As of 09-10-2012

SCHOOL SCHOOL NAME SCHOOL ADDRESS NAME 0133 ABAD SANTOS EDUCATIONAL INSTITUTION SAN BERNARDO ST. NEAR RECTO AVE., MANILA 1105 ABADA COLLEGE PINAMALAYAN, ORIENTAL MINDORO 2399 ABE INTERNATIONAL COLLEGE OF BUSINESS & ACCOUNTANCY-MALOLOS MC ARTHUR H-WAY, MALOLOS CITY, BULACAN 2362 ABE INTERNATIONAL COLLEGE OF BUSINESS & ACCOUNTANCY-URDANETA URDANETA CITY, PANGASINAN 1932 ABE INTERNATIONAL COLLEGE OF BUSINESS & ECONOMICS-BACOLOD BACOLOD CITY, NEGROS OCCIDENTAL 1984 ABE INTERNATIONAL COLLEGE OF BUSINESS & ECONOMICS-CABANATUAN CABANATUAN CITY, NUEVA ECIJA 1894 ABE INTERNATIONAL COLLEGE OF BUSINESS & ECONOMICS-CAINTA CAINTA, RIZAL 1880 ABE INTERNATIONAL COLLEGE OF BUSINESS & ECONOMICS-DAGUPAN DAGUPAN CITY, PANGASINAN 1891 ABE INTERNATIONAL COLLEGE OF BUSINESS & ECONOMICS-DASMARIÑAS DASMARINAS, CAVITE 2012 ABE INTERNATIONAL COLLEGE OF BUSINESS & ECONOMICS-ILOILO ILOILO CITY, ILOILO 2174 ABE INTERNATIONAL COLLEGE OF BUSINESS & ECONOMICS-LAS PIÑAS PAMPLONA, LAS PIÑAS CITY, MM 1911 ABE INTERNATIONAL COLLEGE OF BUSINESS & ECONOMICS-LUCENA QUEZON AVENUE/ZAMORA ST., LUCENA CITY 1581 ABE INTERNATIONAL COLLEGE OF BUSINESS & ECONOMICS-RECTO C. M. RECTO, MANILA 1725 ABE INTERNATIONAL COLLEGE OF BUSINESS & ECONOMICS-TACLOBAN TACLOBAN CITY, LEYTE 1361 ABELLANA COLLEGE OF ARTS & TRADE OSMENA BLVD., CEBU CITY, CEBU 0353 ABELLANA NATIONAL SCHOOL CEBU CITY, CEBU 0403 ABRA STATE INST. OF SCIENCE & TECH.(ABRA IST)-BANGUED BANGUED, ABRA 0029 ABRA STATE INST. OF SCIENCE & TECH.(ABRA IST)-LAGANGILANG LAGANGILANG, ABRA 0469 ABRA VALLEY COLLEGE BANGUED, ABRA 1979 ABUBAKAR COMPUTER LEARNING CENTER BONGAO, TAWI-TAWI 1015 ABUYOG COMMUNITY COLLEGE ABUYOG, LEYTE 2260 ACADEMIA DE SAN LORENZO DEMA-ALA SAN JOSE DEL MONTE, BULACAN 2352 ACCESS COMPUTER & TECHNICAL COLLEGE-MANILA SAMPALOC, MANILA 1860 ACES TAGUM COLLEGE MANKILAM, TAGUM CITY, DAVAO DEL NORTE 1474 ACI COMPUTER COLLEGE (for. -

Nature of Transitioning Among Persons Living with Undetectable HIV

19 “Journey of Uncertainties:” Nature of Transitioning among Persons Living with Undetectable HIV https://doi.org/10.37719/jhcs.2020.v2i1.oa002 RUDOLF CYMORR KIRBY P. MARTINEZ, PhD, MA, RN https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5323-5108 1College of Nursing, San Beda University, Manila, Philippines 2Graduate School of Nursing, Arellano University Juan Sumulong Campus, Manila, Philippines Corresponding author’s email: [email protected] Abstract Introduction: The management of persons living with HIV gears towards making that person “seronegative,” undetectable in screening and practically with almost no risk of transmitting the disease. Although the trajectory of this management is clear, the process by which the person living with HIV transition from being seropositive to seronegative remains to be explored. There remains to be a paucity of research on the nature of transitioning among seronegative persons living with HIV especially from the lens of an Asian nation. Methodology: This study explored the nature of transitioning among nine (9) seronegative persons living with HIV. Grounded on the Rogerian Science of Unitary Human Being as its philosophical underpinning and Gadamerian interpretative phenomenology as its approach, nine (9) informants were selected with the following criteria: They are 1) Persons living with HIV for at least 2 years; 2) Seronegative for at least a year during the time of the interview, and 3) Willing to articulate and share their experiences. After obtaining approval from the University Research Ethics Board, multiple in- depth interviews, story-telling sessions, and photo-elicitation were utilized to gather the informants' narratives. Findings: After a series of reflective analyses, the following nature of transitioning was identified: (1) transitioning as a conscious deliberate choice, (2) transitioning as an unpredictable struggle of being, and (3) transitioning as seeking a personal sense of normalcy. -

Conference Program

MESSAGE FROM THE DEAN I am extending my great appreciation and praises to the team of the 11th National Conference on Research in Teacher Education (NCRTE). You have once again laboriously put together this biennial assembly. I am similarly greeting with conviviality the scholars, practitioners, and students who have joined us in this three-day conference. Welcome to the UP College of Education (UP Ced)! This year’s theme, “Educational Reforms: Reflecting on the Past, Exploring Dynamic Solutions, and Forging New Horizons”, is seeking to understand how the topography of the Philippine educational system is continuously being refined by developments and amendments. These are mirrored and echoed by the eleven strands: 1) trends and innovations in assessment; 2) action research; 3) educational evaluation; 3) child protection; 4) career education; 5) mental health; 6) teacher education and training; 7) teaching, learning, and technology; 8) ICT in school administration; 9) instructional leadership and school performance; 10) educational leadership and policy; and 11) professional and organizational development. Keeping abreast with developments and amendments in the field provides us with the baseline and foundational work in sustaining improvement for our practices and our academic culture. In this year’s NCRTE, we hope to spur imaginative solutions and deepen our understanding of our state of affairs, enabling us to create paths where there previously was one. I also hope that this deepened understanding enables us to see clearly on things that we still know little about. May discussions and exchange of ideas in this year’s conference diminish our thinking that the present is a mere culmination of our former advancements.