With a Compendium of Recollections and Tribute Pieces from Bancom Alumni and Friends

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NATIONAL CAPITAL REGION Child & Youth Welfare (Residential) ACCREDITED a HOME for the ANGELS CHILD Mrs

Directory of Social Welfare and Development Agencies (SWDAs) with VALID REGISTRATION, LICENSED TO OPERATE AND ACCREDITATION per AO 16 s. 2012 as of March, 2015 Name of Agency/ Contact Registration # License # Accred. # Programs and Services Service Clientele Area(s) of Address /Tel-Fax Nos. Person Delivery Operation Mode NATIONAL CAPITAL REGION Child & Youth Welfare (Residential) ACCREDITED A HOME FOR THE ANGELS CHILD Mrs. Ma. DSWD-NCR-RL-000086- DSWD-SB-A- adoption and foster care, homelife, Residentia 0-6 months old NCR CARING FOUNDATION, INC. Evelina I. 2011 000784-2012 social and health services l Care surrendered, 2306 Coral cor. Augusto Francisco Sts., Atienza November 21, 2011 to October 3, 2012 abandoned and San Andres Bukid, Manila Executive November 20, 2014 to October 2, foundling children Tel. #: 562-8085 Director 2015 Fax#: 562-8089 e-mail add:[email protected] ASILO DE SAN VICENTE DE PAUL Sr. Enriqueta DSWD-NCR RL-000032- DSWD-SB-A- temporary shelter, homelife Residentia residential care -5- NCR No. 1148 UN Avenue, Manila L. Legaste, 2010 0001035-2014 services, social services, l care and 10 years old (upon Tel. #: 523-3829/523-5264/522- DC December 25, 2013 to June 30, 2014 to psychological services, primary community-admission) 6898/522-1643 Administrator December 24, 2016 June 29, 2018 health care services, educational based neglected, Fax # 522-8696 (Residential services, supplemental feeding, surrendered, e-mail add: [email protected] Care) vocational technology program abandoned, (Level 2) (commercial cooking, food and physically abused, beverage, transient home) streetchildren DSWD-SB-A- emergency relief - vocational 000410-2010 technology progrm September 20, - youth 18 years 2010 to old above September 19, - transient home- 2013 financially hard up, (Community no relative in based) Manila BAHAY TULUYAN, INC. -

Hbeat60a.Pdf

2 HEALTHbeat I July - August 2010 HEALTH exam eeny, meeny, miney, mo... _____ 1. President Noynoy Aquino’s platform on health is called... a) Primary Health Care b) Universal Health Care c) Well Family Health Care _____ 2. Dengue in its most severe form is called... a) dengue fever b) dengue hemorrhagic fever c) dengue shock syndrome _____ 3. Psoriasis is... a) an autoimmune disease b) a communicable disease c) a skin disease _____ 4. Disfigurement and disability from Filariasis is due to... a) mosquitoes b) snails c) worms _____ 5. A temporary family planning method based on the natural effect of exclusive breastfeeding is... a) Depo-Provera b) Lactational Amenorrhea c) Tubal Ligation _____ 6. The creamy yellow or golden substance that is present in the breasts before the mature milk is made is... a) Colostrum b) Oxytocin c) Prolactin _____ 7. The pop culture among the youth that rampantly express depressing words through music, visual arts and the Internet is called... a) EMO b) Jejemon c) Badingo _____ 8. The greatest risk factor for developing lung cancer is... a) Human Papilloma Virus b) Fats c) Smoking _____ 9. In an effort to further improve health services to the people and be at par with its private counterparts, Secretary Enrique T. Ona wants the DOH Central Office and two or three pilot DOH hospitals to get the international standard called... a) ICD 10 b) ISO Certification c) PS Mark _____ 10. PhilHealth’s minimum annual contribution is worth... a) Php 300 b) Php 600 c) Php 1,200 Answers on Page 49 July - August 2010 I HEALTHbeat 3 DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH - National Center for Health Promotion 2F Bldg. -

The Conflict of Political and Economic Pressures in Philippine Economic

This dissertation has been Mic 61-2821 naicrofilmed exactly as received BRAZIL, Harold Edmund. THE CONFLICT OF POLITICAL AND ECONOMIC PRESSURES m PHILIPPINE ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT. The Ohio State University, Ph.D., 1961 Political Science, public administration University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan THE CONFLICT OF POLITICAL AND ECONOMIC PRESSURES IN PHILIPPINE ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for tjie Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Harold Edmund Brazil, B, S., M. A» The Ohio S tate U niversity 1961 Approved by Adviser Co-Adviser Department of Political Science PREFACE The purpose of this study is to examine the National Economic Council of the Philippines as a focal point of the contemporary life of that nation. The claim is often made that the Republic of the Philippines, by reason of American tutelage, stands as the one nation in the Orient that has successfully established itself as an American-type democracy. The Philippines is confronted today by serious econcanic problems which may threaten the stability of the nation. From the point of view of purely economic considerations, Philippine national interests would seem to call for one line of policy to cope with these economic problems. Yet, time and again, the Philippine government has been forced by political considerations to foUcw some other line of policy which was patently undesirable from an economic point of view. The National Economic Council, a body of economic experts, has been organized for the purpose of form ulating economic p o licy and recommend ing what is economically most desirable for the nation. -

Psychographics Study on the Voting Behavior of the Cebuano Electorate

PSYCHOGRAPHICS STUDY ON THE VOTING BEHAVIOR OF THE CEBUANO ELECTORATE By Nelia Ereno and Jessa Jane Langoyan ABSTRACT This study identified the attributes of a presidentiable/vice presidentiable that the Cebuano electorates preferred and prioritized as follows: 1) has a heart for the poor and the needy; 2) can provide occupation; 3) has a good personality/character; 4) has good platforms; and 5) has no issue of corruption. It was done through face-to-face interview with Cebuano registered voters randomly chosen using a stratified sampling technique. Canonical Correlation Analysis revealed that there was a significant difference as to the respondents’ preferences on the characteristic traits of the presidential and vice presidential candidates across respondents with respect to age, gender, educational attainment, and economic status. The strength of the relationships were identified to be good in age and educational attainment, moderate in gender and weak in economic status with respect to the characteristics of the presidentiable. Also, there was a good relationship in age bracket, moderate relationship in gender and educational attainment, and weak relationship in economic status with respect to the characteristics of a vice presidentiable. The strength of the said relationships were validated by the established predictive models. Moreover, perceptual mapping of the multivariate correspondence analysis determined the groupings of preferred characteristic traits of the presidential and vice presidential candidates across age, gender, educational attainment and economic status. A focus group discussion was conducted and it validated the survey results. It enumerated more characteristics that explained further the voting behavior of the Cebuano electorates. Keywords: canonical correlation, correspondence analysis perceptual mapping, predictive models INTRODUCTION Cebu has always been perceived as "a province of unpredictability during elections" [1]. -

Between Rhetoric and Reality: the Progress of Reforms Under the Benigno S. Aquino Administration

Acknowledgement I would like to extend my deepest gratitude, first, to the Institute of Developing Economies-JETRO, for having given me six months from September, 2011 to review, reflect and record my findings on the concern of the study. IDE-JETRO has been a most ideal site for this endeavor and I express my thanks for Executive Vice President Toyojiro Maruya and the Director of the International Exchange and Training Department, Mr. Hiroshi Sato. At IDE, I had many opportunities to exchange views as well as pleasantries with my counterpart, Takeshi Kawanaka. I thank Dr. Kawanaka for the constant support throughout the duration of my fellowship. My stay in IDE has also been facilitated by the continuous assistance of the “dynamic duo” of Takao Tsuneishi and Kenji Murasaki. The level of responsiveness of these two, from the days when we were corresponding before my arrival in Japan to the last days of my stay in IDE, is beyond compare. I have also had the opportunity to build friendships with IDE Researchers, from Nobuhiro Aizawa who I met in another part of the world two in 2009, to Izumi Chibana, one of three people that I could talk to in Filipino, the other two being Takeshi and IDE Researcher, Velle Atienza. Maraming salamat sa inyo! I have also enjoyed the company of a number of other IDE researchers within or beyond the confines of the Institute—Khoo Boo Teik, Kaoru Murakami, Hiroshi Kuwamori, and Sanae Suzuki. I have been privilege to meet researchers from other disciplines or area studies, Masashi Nakamura, Kozo Kunimune, Tatsufumi Yamagata, Yasushi Hazama, Housan Darwisha, Shozo Sakata, Tomohiro Machikita, Kenmei Tsubota, Ryoichi Hisasue, Hitoshi Suzuki, Shinichi Shigetomi, and Tsuruyo Funatsu. -

INFORMATION to USERS the Most Advanced Technology Has Been

INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photo graph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are re produced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. These are also available as one exposure on a standard 35mm slide or as a 17" x 23" black and white photographic print for an additional charge. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI University Microfilms international A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 Nortfi Zeeb Road. -

Extinguishment of Agency General Condition Revocation Withdrawal Of

Extinguishment of Agency General condition Revocation Withdrawal of agent Death of the Principal Death of the Agent CASES Republic of the Philippines SUPREME COURT Manila FIRST DIVISION G.R. No. L-36585 July 16, 1984 MARIANO DIOLOSA and ALEGRIA VILLANUEVA-DIOLOSA, petitioners, vs. THE HON. COURT OF APPEALS, and QUIRINO BATERNA (As owner and proprietor of QUIN BATERNA REALTY), respondents. Enrique L. Soriano for petitioners. Domingo Laurea for private respondent. RELOVA, J.: Appeal by certiorari from a decision of the then Court of Appeals ordering herein petitioners to pay private respondent "the sum of P10,000.00 as damages and the sum of P2,000.00 as attorney's fees, and the costs." This case originated in the then Court of First Instance of Iloilo where private respondents instituted a case of recovery of unpaid commission against petitioners over some of the lots subject of an agency agreement that were not sold. Said complaint, docketed as Civil Case No. 7864 and entitled: "Quirino Baterna vs. Mariano Diolosa and Alegria Villanueva-Diolosa", was dismissed by the trial court after hearing. Thereafter, private respondent elevated the case to respondent court whose decision is the subject of the present petition. The parties — petitioners and respondents-agree on the findings of facts made by respondent court which are based largely on the pre-trial order of the trial court, as follows: PRE-TRIAL ORDER When this case was called for a pre-trial conference today, the plaintiff, assisted by Atty. Domingo Laurea, appeared and the defendants, assisted by Atty. Enrique Soriano, also appeared. A. -

![THE HUMBLE BEGINNINGS of the INQUIRER LIFESTYLE SERIES: FITNESS FASHION with SAMSUNG July 9, 2014 FASHION SHOW]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7828/the-humble-beginnings-of-the-inquirer-lifestyle-series-fitness-fashion-with-samsung-july-9-2014-fashion-show-667828.webp)

THE HUMBLE BEGINNINGS of the INQUIRER LIFESTYLE SERIES: FITNESS FASHION with SAMSUNG July 9, 2014 FASHION SHOW]

1 The Humble Beginnings of “Inquirer Lifestyle Series: Fitness and Fashion with Samsung Show” Contents Presidents of the Republic of the Philippines ................................................................ 8 Vice-Presidents of the Republic of the Philippines ....................................................... 9 Popes .................................................................................................................................. 9 Board Members .............................................................................................................. 15 Inquirer Fitness and Fashion Board ........................................................................... 15 July 1, 2013 - present ............................................................................................... 15 Philippine Daily Inquirer Executives .......................................................................... 16 Fitness.Fashion Show Project Directors ..................................................................... 16 Metro Manila Council................................................................................................. 16 June 30, 2010 to June 30, 2016 .............................................................................. 16 June 30, 2013 to present ........................................................................................ 17 Days to Remember (January 1, AD 1 to June 30, 2013) ........................................... 17 The Philippines under Spain ...................................................................................... -

From the Library of Garrick Lee Praise for up and out of Poverty

ptg From the Library of Garrick Lee Praise for Up and Out of Poverty “Philip Kotler, pioneer in social marketing, and Nancy Lee bring their inci- sive thinking and pragmatic approach to the problems of behavior change at the bottom of the pyramid. Creative solutions to persistent problems that affect the poor require the tools of social marketing and multi-stakeholder management. In this book, the poor around the world have found new and powerful allies. A must read for those who work to alleviate poverty and restore human dignity.” —CK Prahalad, Paul and Ruth McCracken Distinguished University Pro- fessor, Ross School of Business, The University of Michigan, Ann Arbor; and author of The Fortune at the Bottom of the Pyramid, 5th Anniversary Edition “Up and Out of Poverty will prove very helpful to antipoverty planners and workers to help the poor deal better with their problems of daily living. Philip Kotler and Nancy Lee illustrate vivid cases of how the poor can be helped by social marketing solutions.” —Mechai Viravaidya, founder and Chairman, ptg Population and Community Development Association, Thailand “Helping others out of poverty is a simple task; yet it remains incomplete. Putting poverty in a museum is achievable within a short span of time—if we all work together, we can do it!” —Muhammad Yunus, winner of the Nobel Prize for Peace; and Managing Director, Grameen Bank “In Up and Out of Poverty, Kotler and Lee remind us that ‘markets’ are peo- ple. A series of remarkable case studies demonstrate conclusively the power of social marketing to release the creative energy of people to solve their own problems. -

Upsurge of People's Resistance in the Philippines and the World

Jose Maria Sison Upsurge of People’s Resistance in the Philippines and the World Selected Works 2020 Julieta de Lima, Editor Table of Contents Title Page Upsurge of People's Resistance in the Philippines and the World Author’s Preface I. Articles and Speeches Terrorist crimes of Trump and US imperialism | turn the peoples of the Middle East against them On the Prospect of Peace Negotiations during the Time of Duterte or Thereafter1 Fight for Land, Justice and Peace | Message on the Occasion of 33rd Anniversary | of the Mendiola massacre2 Celebrate the First Quarter Storm of 1970, | Honor and Emulate the Heroic Activist Youth Relevance of the First Quarter Storm of 1970 | to the Global Anti- Fascist In Transition to the Resurgence of the | World Proletarian Revolution In Transition to the Resurgence of the | World Proletarian Revolution4 On the International Situation, | Covid-19 Pandemic and the People’s Response5 | First Series of ILPS Webinars In Transition to the Resurgence | of the World Proletarian Revolution6 An Update on the International Situation7 | for the International Coordinating Committee | of the International League of Peoples’ Struggle ILPS as United Front for Anti-Imperialist and | Democratic Struggle | Message on the Plan to Establish the ILPS-Europe8 A Comment on Dialectical Materialism, Idealism | and Mechanical Materialism Lenin at 150: Lenin Lives!9 | In Celebration of the 150th birth anniversary | of V.I. Lenin On the Current Character of the Philippine Economy General View of Lenin’s Theory on | Modern Imperialism -

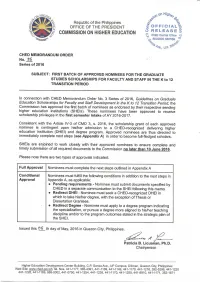

CMO No. 26, Series of 2016

List of Approved SHEI Nominees for Graduate Scholarships in the K to 12 Transition Program BATCH 1 SENDING HIGHER REGION EDUCATION NAME OF FACULTY / PROGRAM TITLE APPLIED FOR PROGRAM DELIVERING HEI (IF REMARKS INSTITUTION (SHEI) STAFF STATUS KNOWN/PROSPECTIVE) 1 ASIACAREER Reyno, Miriam Joy M. Master in Business Administration New Master's Lyceum-Northwestern Redirect Degree, COLLEGE University Redirect DHEI FOUNDATION, INC. 1 COLEGIO DE Baquiran, Brylene Ann Doctor of Philosophy major in New Doctorate Not Stated DAGUPAN R. Educational Management Bautista, Chester Allan Doctor in Information Technology New Doctorate Not Stated Redirect Degree F. Caralos, Edilberto Jr. L. Master in Information Technology New Master's Not Stated Columbino, Marvin B. MS Electronics Engineering New Master's Saint Louis University Dela Cruz, Anna Clarissa Master in Information Technology New Master's Not Stated R. Dela Cruz, Vivian A. Doctor of Philosophy Ongoing Not Stated Doctorate Fernandez, Hajibar Master in Information Technology New Master's Not Stated Jhoneil L. Fortin, Arnaldy D. Doctor in Information Technology New Doctorate Not Stated Gabriel, Jr. Renato J. Master in Communication major New Master's De La Salle University, Taft in Applied Medical Studies Page 1 of 183 Lachica, Evangeline N. Doctor in Information Technology New Doctorate Not Stated Landingin, Mark Joseph Master of Arts in Philosophy New Master's Not Stated D. Macaranas, Jin Benir C. Master of Science in Electrical New Master's Saint Louis University Engineering Navarro, Adessa Bianca Master in Business Administration Ongoing Not Stated G. Master's Ordonez, Jesse Jr. P. Doctor of Philosophy New Doctorate Not Stated Seco, Cristian Rey C. -

The Politics of Economic Reform in the Philippines the Case of Banking Sector Reform Between 1986 and 1995

The Politics of Economic Reform in the Philippines The Case of Banking Sector Reform between 1986 and 1995 A thesis submitted for the degree of PhD School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) University of London 2005 Shingo MIKAMO ProQuest Number: 10673052 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10673052 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 2 Abstract This thesis is about the political economy of the Philippines in the process of recovery from the ruin of economic crisis in the early 1980s. It examines the dynamics of Philippine politics by focussing on banking sector reform between 1986 and 1995. After the economic turmoil of the early 1980s, the economy recovered between 1986 and 1996 under the Aquino and Ramos governments, although the country is still facing numerous economic challenges. After the "Asian currency crisis" of 1997, the economy inevitably decelerated again. However, the Philippines was seen as one of the economies least adversely affected by the rapid depreciation of its currency. The existing literature tends to stress the roles played by international financial structures, the policy preferences of the IMF, the World Bank and the US government and the interests of the dominant social force as decisive factors underlying economic and banking reform policy-making in the Philippines.