Humanum Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Biography of Pope John Paul Ii Pdf

Biography of pope john paul ii pdf Continue John Paul II (1920-2005) CAROL JASEF VODYA, elected Pope on October 16, 1978, was born on May 18, 1920, in Wadowice, Poland. He was the third of three children born to Karol Oytytya and Emilia Kakovsky, who died in 1929. His older brother Edmund, a doctor, died in 1932, and his father, Carol, a non-commissioned officer in the army, died in 1941. He was nine years old when he received his First Communion and eighteen years when he received the Sacrament of Confirmation. After graduating from high school in Vadowice, he enrolled at the University of Jagelon in Krakow in 1938. When the Nazi occupying forces closed the university in 1939, Karol worked (1940-1944) in a quarry and then at the Solvea chemical plant to earn a living and avoid deportation to Germany. Feeling called to the priesthood, he began his studies in 1942 at a secret large seminary in Krakow under the direction of Archbishop Adam Stefan Sapiehi. At the time, he was one of the organizers of the Rhapsodic Theatre, which was also underground. After the war, Carol continued his studies at the main seminary, recently reopened, and at the School of Theology at Jagelon University, before his priestly ordination in Krakow on November 1, 1946. Father Oytysha was then sent by Cardinal Sapieha to Rome, where he received his doctorate in theology (1948). He wrote his thesis on faith, as is understood in the works of St. John the Cross. As a student in Rome, he spent his holidays performing pastoral service with Polish expats in France, Belgium and Holland. -

Pontifical John Paul Ii Institute for Studies on Marriage & Family

PONTIFICAL JOHN PAUL II INSTITUTE FOR STUDIES ON MARRIAGE & FAMILY at The Catholic University of America, Washington, D.C. ACADEMIC CATALOG 2011 - 2013 © Copyright 2011 Pontifical John Paul II Institute for Studies on Marriage and Family at The Catholic University of America Cover photo by Tony Fiorini/CUA 2JOHN PAUL II I NSTITUTE TABLE OF CONTENTS MISSION STATEMENT 4 DEGREE PROGRAMS 20 The Master of Theological Studies NATURE AND PURPOSE in Marriage and Family OF THE INSTITUTE 5 (M.T.S.) 20 The Master of Theological Studies GENERAL INFORMATION 8 in Biotechnology and Ethics 2011-12 A CADEMIC CALENDAR 10 (M.T.S.) 22 The Licentiate in Sacred Theology STUDENT LIFE 11 of Marriage and Family Facilities 11 (S.T.L.) 24 Brookland/CUA Area 11 Housing Options 11 The Doctorate in Sacred Theology Meals 12 with a Specialization in Medical Insurance 12 Marriage and Family (S.T.D.) 27 Student Identification Cards 12 The Doctorate in Theology with Liturgical Life 12 a Specialization in Person, Dress Code 13 Marriage, and Family (Ph.D.) 29 Cultural Events 13 Transportation 13 COURSES OF INSTRUCTION 32 Parking 14 FACULTY 52 Inclement Weather 14 Post Office 14 THE MCGIVNEY LECTURE SERIES 57 Student Grievances 14 DISTINGUISHED LECTURERS 57 Career and Placement Services 14 GOVERNANCE & A DMINISTRATION 58 ADMISSIONS AND FINANCIAL AID 15 STUDENT ENROLLMENT 59 TUITION AND FEES 15 APOSTOLIC CONSTITUTION ACADEMIC INFORMATION 16 MAGNUM MATRIMONII SACRAMENTUM 62 Registration 16 Academic Advising 16 PAPAL ADDRESS TO THE FACULTY OF Classification of Students 16 Auditing -

(Mk 1:22). on the Role of Wonderment in the Theological Method

Teologia w Polsce 14,2 (2020), s. 49–62 10.31743/twp.2020.14.2.03 Fr. Cezary Smuniewski* Akademia Sztuki Wojennej, Warszawa “ET STUPEBANT SUPER DOCTRINA EJUS” (MK 1:22). ON THE ROLE OF WONDERMENT IN THE THEOLOGICAL METHOD The study is a contribution to research on the theological method and shows the motif of wonderment in the teaching and poetry of John Paul II as an experience inviting man to get to know God and His works ever more deeply. The human experience of being amazed with God has been presented as a theological event – a grace of the ability to stand in awe of God, to get closer to Him and to speak about Him. The author of the article comes to the conclusion that the mission of a theologian is inseparably connected with cultivating the ability to be amazed with God and His works. The experience of wonderment is one of the elements leading to communion with Christ the Theologian, who reveals the Father. INTRODUCTION The aim of this study is to show the motif of wonderment and at the same time to try to recognize in this motif the content that can be useful in research on the theological method and thus indirectly on the mission of the theologian. The choice of sources which became the basis for the analysis was determined by the main idea – striving to show wonderment as one of the elements influencing the theological thinking and the experience of faith. The quoted documents and studies were selected with regard to their relation to the theological and semantic problem space, defined by the main goal. -

X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X

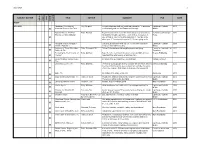

2/25/2020 1 SUBJECT MATTER TITLE AUTHOR SUMMARY PUB DATE DVD gdom VIDEO AUDIO OTHER OTHER AUDIO 2/12/2020 Abraham: Revealing the Ray, Stephen To understand our faith, we must understand the "Jewishness" Lighthouse Catholic 2011 x Historical Roots of our Faith of Christianity and our Old Testament Heritage Media Adam's Return: The Five Rohr, Richard Boys become men in much the same way across cultures, by St. Anthony Messenger 2006 Promises of Male Initiation integrating, through experience, each of these messages: 1. Press x Life is hard; 2. You are not that important; 3. Your life is not about you; 4. You are not in control; 5. You are going to die. Amazing Angels and Super Cat.Chat, designed for kids ages 3-11, to teach lessons for Lighthouse Catholic 2008 x Saints - Episode 1 living out their faith every day Media Authority of Those Who Have Rohr, Richard OFM Father Richard shares his insights on pain and dying Center for Loss and Life 2005 x Suffered, The Transition Becoming the Best Version of Kelly, Matthew Take life to the next level: who you become is infinitely more Beacon Publishing 1999 x Yourself important than what you do or what you have. Best of Catholic Answers Live, 47 answers to questions from non-Catholics Catholic Answers x The Best Way to Live, The Kelly, Matthew Perfect for young paople as they consider the life before them at Beacon Publishing 2012 the time of Confirmation; also an important reminder for adults x of any age, and one that is sure to help you refocus your life x Bible, The Recitation of the Bible on 64 cd's Zondervan 2001 Body and Blood of Christ, The Hahn, Dr. -

The BG News March 25, 2004

Bowling Green State University ScholarWorks@BGSU BG News (Student Newspaper) University Publications 3-25-2004 The BG News March 25, 2004 Bowling Green State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news Recommended Citation Bowling Green State University, "The BG News March 25, 2004" (2004). BG News (Student Newspaper). 7259. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news/7259 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Publications at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in BG News (Student Newspaper) by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@BGSU. State University THURSDAY March 25, 2004 SHOWERS HIGH: 631 LOW: 54 www.bgnews.com independent student press VOLUME 98 ISSUE 117 Alumni speaks about STAND By Monica Frost seen and heard throughout Ohio for the STAND'S campaign strategy moves up a based groups. REPORTER past three years in print ads as well as hierarchy of education and awareness, "It's kids talking to kids," Miller said of Rick Miller, a 1979 University graduate, radio and television spots. empowerment, activism and the ultimate STAND'S street-approach. "It's people shared with students and faculty yestei- Miller's speech was titled "Apathy to goal of a cultural shift where "tobacco is talking from their hearts about something day evening some very interesting num- Advocacy: Changing Ohio's Culture no longer culturally accepted in Ohio," that's tmly important to them." bers concerning tobacco use in the state Regarding Tobacco Use" and was a pan of Miller said. -

Dominum Et Vivificantem

SUMMARY Year 2003 marks the 25th anniversary of Card. Karol Wojtyła’s appointment to Peter’s See. The present volume of the Ethos, entitled T he Ethos of the Pilgrim, is thought as an attempt to point to the most genuine aspect of this outstandingly prolific pontificate. This special attribute of John Paul II*s pontificate can be perceived in the fact that the Pope has construed his mission as that of a Pilgrim. Indeed, peregrination appears to constitute a special dimension of John Paul II’s service to humanity. Pilgrimages have been a most significant instrument of the Holy Father’s apostolic mission already sińce the start of the pontificate, beginning with the trip to Santo Domingo and Mexico in January 1979. Actually, the agenda of John Paul II’s pontificate, which was to become a Pilgrim one, was clearly outlined in the homily delivered by the Pope in Victory Sąuare in Warsaw on 2 June 1979. The Holy Father said then: “Once the Church has realized anew that being the People of God she participates in the mission of Christ, that she is the People that conducts this mission in history, that the Church is a «pilgrim» people, the Pope can no longer remain a prisoner in the Vatican. He has had no other choice, but to become, once again, pilgrim-Peter, just like St. Peter himself, who became a pilgrim from Antioch to Rome in order to bear witness to Christ and to sign it with his blood.” From the perspective of the last 25 years one can observe a perfect coherence that marks the implementation of this agenda. -

The Communional Rhythm of Life. the Personalistic Meditation on Human Life According to Karol Wojtyla/John Paul Ii *

Synesis, v. 6, n. 2, p. 122-139, jul/dez. 2014, ISSN 1984-6754 © Universidade Católica de Petrópolis, Petrópolis, Rio de Janeiro, Brasil THE COMMUNIONAL RHYTHM OF LIFE. THE PERSONALISTIC MEDITATION ON HUMAN LIFE ACCORDING TO KAROL WOJTYLA/JOHN PAUL II * MASSIMILIANO POLLINI LUDWIG-MAXIMILIANS-UNIVERSITY MUNICH, GERMANY Mas ¿cómo perseveras, ¡oh vida!, no viviendo donde vives, y haciendo por que mueras las flechas que recibes de lo que del Amado en ti concibes?1 Gloria Dei vivens homo, vita autem hominis visio Dei. (…) Haec enim gloria hominis, perseverare ac permanere in Dei servitute2 Zapoczątkował w nich miejsce urodzin i miejsce życia odsłonił w każdym człowieku, które przerasta nurt mijania, które przerasta śmierć3 Abstract: In this brief paper I attempt to focus our attention on some of the main thematic lines concerning Karol Wojtyła’s meditation both on man’s personhood and man’s life. I especially wish to investigate the meaning of the term «life», such as it is used in the thought and the teachings of the man who became John Paul II. Keywords: Karol Wojtyla; personalism; nature; person; life. Resumo: Neste breve ensaio, pretendo prestar atenção a uma das principais linhas temáticas da meditação de Karol Wojtyla sobre a personalidade humana e a vida do homem. Almejo especialmente investigar o significado do termo “vida”, tal como é usado no pensamento e nos ensinamentos do homem que se tornou João Paulo II. Palavras-chave: Karol Wojtyla; personalismo; natureza; pessoa; vida. Artigo recebido em 15/12/2014 e aprovado para publicação pelo Conselho Editorial em 23/12/2014. PhD Student at the Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München (Faculty of Philosophy). -

Saint John Paul II (1978-2005)

Saint John Paul II (1978-2005) His Holiness John Paul II (16 Oct. 1978-2 April 2005) was the first Slav and the first non-Italian Pope since Hadrian VI. Karol Wojtyla was born on 18 May 1920 at Wadowice, an industrial town south-west of Krakow, Poland. His father was a retired army lieutenant, to whom he became especially close since his mother died when he was still a small boy. Joining the local primary school at seven, he went at eleven to the state high school, where he proved both an outstanding pupil and a fine sportsman, keen on football, swimming, and canoeing (he was later to take up skiing); he also loved poetry, and showed a particular flair for acting. In 1938 he moved with his father to Krakow where he entered the Jagiellonian University to study Polish language and literature; as a student he was prominent in amateur dramatics, and was admired for his poems. When the Germans occupied Poland in September 1939, the university was forcibly closed down, although an underground network of studies was maintained (as well as an underground theatrical club which he and a friend organised). Thus he continued to study incognito, and also to write poetry. In winter 1940 he was given a labourer’s job in a limestone quarry at Zakrówek, outside Krakow, and in 1941 was transferred to the water- purification department of the Solway factory in Borek Falecki; these experiences were to inspire some of the more memorable of his later poems. In 1942, after his father’s death and after recovering from two near-fatal accidents, he felt the call to the priesthood, began studying theology clandestinely and after the liberation of Poland by the Russian forces in January 1945 was able to rejoin the Jagiellonian University openly. -

NEW SUNDAY April 27, 2014 SECOND SUNDAY of the RESURRECTION

NEW SUNDAY April 27, 2014 SECOND SUNDAY OF THE RESURRECTION SAINT MARON MARONITE CATHOLIC CHURCH Mailing Address: 7800 Brookside Road Independence, Ohio 44131 Upcoming Events Rev. Fr. Peter Karam, Pastor email: [email protected] MCFP Rev. Fr. George Hajj, Associate Pastor email: [email protected] Sunday, April 27 Rev. Deacon George Khoury MYA Mr. Bechara Daher, Subdeacon Sunday, April 27 Mr. Lattouf Lattouf, Subdeacon Mr. Ghazi Faddoul, Subdeacon 50+ Mr. Georges Faddoul, Subdeacon Friday, May 2 Holy Communion Office Phone: 216.520.5081 Emergency Phone: 216.333.0760 Sunday, May 4 ICS Monday, May 5 Divine Liturgy Schedule Sons of Mary Weekdays: Chapel Monday, May 5 10:00 am Sunday: Downtown May Crowning 9:30 am - English 11:00am - Arabic & English Sunday, May 25 Saturday: Chapel: 5:00 pm Holy Days of Obligation 7pm MISSION STATEMENT We, the people of Saint Maron Parish, form a BAPTISM - community of disciples dedicated to a shared faith and Call the office at least 2 months in advance. common life which exemplifies the life, works, and MARRIAGE - teaching of Jesus Christ as reflected in the Sacred Call at least 8 months in advance. Scriptures and the Maronite Catholic Tradition. Our SACRAMENT OF RECONCILIATION - Parish life and mission are to proclaim the Gospel, to By appointment foster and strengthen the faith, and to evangelize. Our SACRAMENT OF ANOINTING/SICK CALLS covenant of discipleship with Jesus Christ is fulfilled Call the Parish Office immediately. 216.520.5081 or 216.333.0760 through liturgy, education, and service. E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.saintmaron-clev.org Facebook: SaintMaronChurch Office Hrs: Mon-Fri. -

Spring: the Canonizations of Saints John XXIII and John Paul II

WINDSOR to WOODSTOCK, GODERICH to PORT DOVER and COMMUNITIES IN-BETWEEN Spring 2014 • #152 OF NEWSPAPER THE DIOCESE OF LOndON Amherstburg | Aylmer | Belle River | Blenheim | Brights Grove | Brussels | Chatham | Comber | Corunna | Courtland | Delaware | Delhi | Dresden | Dublin | Emeryville | Erieau | Essex | Exeter | Forest | Glencoe | Goderich | Grand Bend | Harrow | Ingersoll | Kingsville | Kinkora | Langton | LaSalle | Leamington | Listowel | London | Lucan | Maidstone | McGregor | Merlin | Mitchell | Mount Carmel | Oxley | Pain Court | Parkhill | Pelee Island | Petrolia | Port Dover | Port Lambton | Ridgetown | River Canard | Rondeau | Sarnia | Seaforth | Sebringville | Simcoe | St. Joseph | St. Marys | St. Thomas | Stratford | Strathroy | Tecumseh | Thamesville | Tilbury | Tillsonburg | Wallaceburg | Walsh | Waterford | Watford | West Lorne | Wheatley | Windsor | Wingham Woodslee | Woodstock | Zurich Saint John XXIII Saint John Paul II On Sunday, April 27, the fear, when the threat of nuclear us remember the words he build the civilization of love.” of Divine Mercy. whole Church celebrated war was brought to a head. In proclaimed at his election: the canonization of Pope his famous Encyclical, Peace “Be not afraid. Open wide the Throughout his papacy, he was He believed that each one of John XXIII and Pope John on Earth, he implored world doors for Christ.” For the next a tireless defender of the dignity us is called to holiness and he Paul II. During their years leaders to work for a genuine 26 years, he proclaimed this of every person – born or knew that we needed the saints in the papacy, they were peace built on justice and not a message through his writings unborn, rich or poor, healthy or to inspire us on our journey. extraordinary pastors whose false peace secured by nuclear and his travels around the sick, oppressed or free. -

To Discover the Project of Life with Saint John Paul II

World Youth Day 2016 Krakow. The School of Faith and Humanity, eds. by J. Stala, P. Guzik, The Pontifical University of John Paul II in Krakow Press, Krakow 2018, p. 109–125 ISBN 978-83-7438-735-4 (print), ISBN 978-83-7438-736-1 (online) DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15633/9788374387361.08 Rev. Michał Drożdż Pontifical University of John Paul II in Krakow, Poland To discover the project of life with Saint John Paul II 1. Introduction World Youth Day is not only a great spiritual experience in the religious di- mension, meeting with God in a community of young people from around the world, fascinated by the person of Jesus Christ, but also a manifesta- tion of the beauty of youth in the dimension of life, enthusiasm, a model of fascination with pure, unadulterated values, an expression of the cour- age of life ideals and imitation of real authorities, testimony to the civi- lization of life and love. That is why it is worth keeping the spirit and at- mosphere of this meeting, those relations, this community, and acting in the testimonies of young people. They are an authentic sign of a youthful project of life based on trust in Jesus and His Good News. These testimo- nies are also a living seal on so many pages of life built up in the commu- nity of disciples and friends of Christ. Youth are always fascinating. Young people on one hand reflect the nat- ural fascination with great, unpolluted values and ideals, and on the other hand, they reflect on their lives all attempts to search for valuable proj- 110 ects of life in a world of destroyed real authorities and values. -

The Beauty of Man a Synopsis of St

The Beauty of Man A Synopsis of St. John Paul II's Theology of the Body by Rev. Benjamin P.Bradshaw, STL The Beauty of Man: A Synopsis of St. Pope John Paul II’s Theology of the Body Rev. Benjamin P. Bradshaw, STL 1 For Joseph Ratzinger (Pope Emeritus) 2 Preface: Pope Francis has noted that too often there exists an inappropriate rift between the realm of theology and that of the lived realities of the lay faithful in the pews: Not infrequently an opposition between theology and pastoral ministry emerges, as if they were two opposite, separate realities that had nothing to do with each other. We not infrequently identify doctrine with conservatism and antiquity; and on the contrary, we tend to think of pastoral ministry in terms of adaptation, reduction, accommodation. As if they had nothing to do with each other. A false opposition is generated between theology and pastoral ministry, between Christian reflection and Christian life. … The attempt to overcome this divorce between theology and pastoral ministry, between faith and life, was indeed one of the main contributions of Vatican Council II.1 For his part, Joseph Ratzinger has noted that there is clearly an “ecclesial vocation” by which the- ologians, in the dedication of their work, partake.2 If theology is truly to be “done on one’s knees,” at some point it must make the leap from the classroom to the pew and from the pew to lived realities of those sitting in the pews on any given Sunday.3 The argument could be made that few transitions are more needed in our own time than for St.