The Ring and the Trial

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Premium List AKC Obedience & Rally Trials Two Back-To-Back Saturday & Sunday August 28Th & 29Th, 2021 NO GERMAN SH

Premium List AKC Obedience & Rally Trials Carpentersville, IL 60110 1510Meadowsedge Ln RobinWalsh Car-Dun-Al O.D.T.C. O.D.T.C. Car-Dun-Al Obedience Event #’s 2021055025 & 2021055026 Rally Event #’s 2021055047 & 2021055048 Unbenched - Indoors (Licensed by the American Kennel Club) Two Back-To-Back Obedience and Rally Trials Saturday & Sunday th th August 28 & 29 , 2021 NO GERMAN SHEPHERDS ON SUNDAY, AUGUST 29TH Car-Dun-Al ODTC Building 10783 Wolf Drive Huntley, Illinois 60142 DO NOT mail entries to this address Trial Hours: 7:00 to 6:00 P.M. CST. “Entries will be accepted for dogs listed in the AKC Canine partners Program” Rally is limited to 100 entries per day. Obedience is limited to 8 hours of judging per day Certification: Permission has been granted by the American Kennel Club for holding this event under American Kennel Club Rules and Regulations. Gina DiNardo, Secretary Car-Dun-Al Obedience Dog Training Club OBEDIENCE TRIAL TROPHY & PRIZE LIST RIBBON PRIZES - ALL OBEDIENCE CLASSES President Jerry McEvilly 1st. Vice President Carol Preble First Place……..…Blue Rosette Second Place….…Red Rosette Third Place…….Yellow Rosette Fourth Place……White Rosette nd 2 . Vice President Bonnie Morrow A Green Ribbon will be awarded to each dog receiving a Qualifying Score. Corresponding Secretary Martha LaLoggia 9265 S Union Rd, Huntley, IL. 60142 Highest Scoring Dog in Regular Classes………....…..Blue & Gold Rosette Recording Secretary Heidi Nelson Highest Combined Score in Open B & Utility……….Blue & Green Rosette Treasurer John Opatrny Director of -

Finnish Champion Title Regulations 2020

FINNISH CHAMPION TITLE REGULATIONS 2020 1 FINNISH CHAMPION TITLE REGULATIONS Valid as of 1.1.2020. This document is a translation of the original version in Finnish, Suomen Valionarvosäännöt 2020. In cases of doubt, the original version will prevail. REQUIREMENTS APPLIED TO ALL BREEDS Finnish Show Champion (FI CH) At least three certificates obtained in Finnish dog shows under three different judges. At least one of these certificates must be obtained at the minimum age of 24 months. Possible breed-specific requirements regarding trial results will also have to be met. The change enters into force on 1.6.2011. (Council 29/5/11) The requirements regarding trial results are minimum requirements. For a dog that has a Finnish owner / holder, results in breed-specific trials gained in Nordic countries count towards the Finnish Show Champion title. (Council 24/11/07) Finnish Agility Champion (FI ACH) A dog is awarded the Finnish Agility Champion title once it has been awarded three Agility Certificates in the highest class in Agility, under three different Agility judges. In addition, the dog must have obtained at least the quality grade good at a dog show at the minimum age of 15 months. A foreign dog is awarded the Finnish Agility Champion title, once it has obtained the national Agility Champion title of its country and has been awarded one Agility Certificate in the highest class in Agility in Finland. (Council 23/11/2019) Finnish Jumping Champion (FI ACH-J) A dog is awarded the Finnish Agility Jumping Champion title once it has been awarded three Jumping Certificates in the highest class in Agility, under three different Agility judges. -

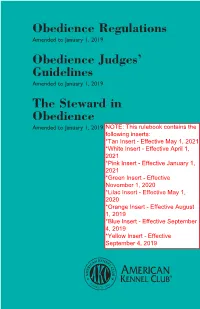

AKC Obedience Regulations Applicable to the Class in Which the Dog Is Entered

Obedience Regulations Amended to January 1, 2019 Obedience Judges’ Guidelines Amended to January 1, 2019 The Steward in Obedience Amended to January 1, 2019 AMERICAN KENNEL CLUB’S MISSION STATEMENT The American Kennel Club is dedicated to upholding the integrity of its Registry, promoting the sport of purebred dogs and breeding for type and function. Founded in 1884, the AKC and its affiliated organizations advocate for the purebred dog as a family companion, advance canine health and well-being, work to protect the rights of all dog owners and promote responsible dog ownership. Revisions to the Obedience Regulations Effective May 1, 2021 This insert is issued as a supplement to the Obedience Regulations amended to January 1, 2019 and approved by the AKC Board of Directors February 9, 2021 CHAPTER 1 – OBEDIENCE REGULATIONS GENERAL REGULATIONS Section 3. Premium Lists, Entries, Closing of Entries. (paragraph 5) The premium list shall specify the name and address of the Superintendent or Trial Secretary who is to receive the entries. Only one mailing address may be used for receipt of paper of entries. Paper entries delivered to any other address are invalid and must be returned to the sender. Section 27. Limitation of Entries and Methods of Entry. If a club anticipates an entry to exceed the capacity of its facilities for a licensed or member trial, it may limit entries, not to exceed up to eight hours of judging time per day, per judge. Prominent announcement of such limits will appear on the title or cover page of the premium list for an obedience trial or immediately under the obedience heading in the premium list for a dog show. -

Official Ukc Obedience Rulebook

OFFICIAL UKC OBEDIENCE RULEBOOK JANUARY 1, 2021 *REVISED JULY 27, 2021 OFFICIAL OBEDIENCE RULEBOOK TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter 1 - General Rules ............................................................................................................................................................... 2 Chapter 2 – Ring and Equipment Requirements ............................................................................................................................. 4 Chapter 3 – Exhibitor and Spectator Conduct at UKC Events .......................................................................................................... 5 Chapter 4 – Rules Applying to Exhibitors ........................................................................................................................................ 5 Chapter 5 – Entry Eligibility for Licensed Classes ............................................................................................................................ 7 Chapter 6 – Rules Applying to Licensed Classes ............................................................................................................................ 10 Chapter 7 – Ring Procedures ......................................................................................................................................................... 10 Chapter 8 – Judging Standards, General Scoring and Deductions ................................................................................................. 11 Chapter 9 – Judging Procedures ................................................................................................................................................... -

The Alaskan Malamute Club of America, Inc. Combined

THE ALASKAN MALAMUTE CLUB OF AMERICA, INC. Alaskan Malamute Club of America, Inc. COMBINED PREMIUM LIST Member of the American Kennel Club Two Specialties – One Location Northeast REGIONAL Specialty & NATIONAL Specialty Shows Northeast Regional Specialty Sunday, October 10 – Tuesday, October 12, 2021 Conformation & Jr. Showmanship #2021011454 Sweepstakes & Veteran Sweepstakes #2021011453 Obedience #2021011451 Rally #2021011423 (held on Wednesday) 4-6 Month Beginner Puppy #2021011455 Northeast National Specialty Wednesday, October 13 – Saturday, October 16, 2021 Conformation & Jr. Showmanship #2021011449 Sweepstakes & Veteran Sweepstakes #2021011448 Futurity/Maturity – 2021011448 Obedience #2021011452 (held on Tuesday) Rally #2021011424 4-6 Month Beginner Puppy #2021011450 THESE SHOWS WILL BE HELD INDOORS – UNBENCHED. Regional & National Specialty AKC Agility Trials Monday, 10/11 & Tuesday, 10/12/2021 Northeast Regional Specialty Show Allstar Events Complex, 2638 Emmitsburg Rd, Gettysburg, PA Sunday, October 10 – Tuesday, October 12, 2021 AGILITY ENTRIES CLOSE WEDNESDAY, SEPTEMBER 22ND National Specialty Show Event Secretary: Denise Thomas, Countryside Agility Wednesday, October 13 – Saturday, October 16, 2021 2321 West 38th St, Erie, PA 16506 [email protected] 814-315-6668 Event Chair: Laura Heft, 66 Old Falls Blvd., No. Tonawanda, NY 14120 AMCA’S Annual Membership Meeting [email protected] 716-425-4468 Wednesday morning, October 13th Premium List available at: Countryside Agility Online Entry Service: Agility On Line Entries -

OTCH Obedience Trial Premium

Directions to Site: I-81 to Exit 57 (PA Route 114); proceed north on Route 114 approximately Due to Covid-19 regulations, limited crating in the building will be allowed. 1 mile. At the signal light at the intersection of Routes 114 and 944 (Wertzville No lunch will be served. Masks must be worn when inside. Road) go straight, take the second right past the signal turn in the lot. The Temperatures will be checked. If you don’t feel well, STAY HOME! OTCH building is the cream-colored building with a green stripe behind the Rite Aid Pharmacy. Entries must be received by April 17, 2021, after which Setting your GPS device to the street address is pretty reliable: time entries will be considered Day of Show entries 1 Souder Court, Mechanicsburg, PA. PREMIUM LIST Where to stay: Consult this web site: UKC RALLY & OBEDIENCE TRIALS https://www.bringfido.com/lodging/city/mechanicsburg_pa_us/ Licensed by the United Kennel Club Red Roof Inn offers special rates: • Carlisle PA, 1450 Harrisburg Pike: $57 through 4/29, then goes up to $65 through 11/11. ($70 Fri/Sat nights) • Harrisburg North, 300 Corporate Cir: $48.99 through 4/29, the goes up to $55.99 through 11/11 ($56.99 Fri/Sat nights) • Harrisburg South, 950 Eisenhower Blvd: $48.99 through 4/29, the goes up to $55.99 through 11/11 ($55.99 Fri/Sat nights) Holiday Inn Express (4.4 mi. from trial site) 6325 Carlisle Pike, Mechanicsburg, PA 17050; (717) 790-0924. Mention OTCH for a price of $92.65 (with tax) and only one dog charge; free breakfast included. -

Premium List

PREMIUM LIST TRI-VALLEY WORKING DOG CLUB of Pinon Hills, Inc. THE KENNEL CLUB OF RIVERSIDE LAKE PERRIS STATE RECREATION AREA PERRIS, CALIFORNIA Friday, October 29, 2021 Tri-Valley Working Dog Club of Pinon Hills Working Group Shows with Sweepstakes, NOHS, All Breed Obedience and Rally Saturday, October 30, 2021 All Breed Dog Show, Obedience and Two Rally Trials, Pee Wee National Owner-Handled Series This show is limited to 1500 entries, limited to 50 entries per Rally trial, limited to 8 hours of Obedience entries Concurrent Specialty: Cocker Spaniel Club of Southern California Sunday, October 31, 2021 All Breed Dog Show Beginner Puppy 4-6 Months National Owner-Handled Series This show is limited to 1500 entries Close of entries: Noon Wednesday, October 13, 2021 PDT 1 IMPORTANT NOTICE Mail Entries with Fees to Jack Bradshaw, 320 Maple Avenue, Torrance, CA 90503 Make checks payable to Jack Bradshaw FAX: (323) 727-2949 E-MAIL ENTRIES: www.jbradshaw.com For entries made online there will be a service fee of $4.00 per dog per show. There will be a $4.00 service fee if entries are cancelled for any reason per dog per show. These service fees are non-refundable. Include MasterCard, Visa or American Express number & expiration date. There will be a $4.00 convenience fee charged per dog per show when using a credit card for payment of hand delivered or mailed in entries. Fax machines are available 24 hours a day. Hand Deliveries - 320 Maple Avenue, Torrance, CA 90503 All entries with fees must be in the office of the Superintendent not later than NOON WEDNESDAY, OCTOBER 13, 2021 PDT Limited to 1500 entries, 50 entries per Rally trial, Obedience 8 hours After which time no entries may be accepted, cancelled, changed, substituted, corrected, completed, or signed and no entry fees refunded. -

Premium List

Obedience #2019243701 – Rally #2019243702 #2019243703 The trial Secretary will assign entries as they are received. Therefore, entries for each judge assigned to specific classes of obedience will be closed when 8 hours of judging has been reached. Rally Limit 70 each Trial ENTRIES CLOSE : 3:00 PM, WEDNESDAY, February 27, 2019 at Secretary’s home after which time entries cannot be accepted, canceled or substituted EXCEPT as provided for in Chapter 11, Section 6 of the Dog Show Rules. Premium list FIFTY SIXTH OBEDIENCE Eighteenth & Ninteenth RALLY (Unbenched) CHARLES RIVER DOG TRAINING CLUB, Inc. (Licensed by American Kennel Club) MASTERPEACE DOG TRAINING 264 Fisher Street, Franklin, MA 508-553-9300 SATURDAY, March 16, 2019 SUNDAY, March 17, 2019 Show Hours 7:00 AM TO 6:00 PM This show will be held indoors TRIAL SECRETARY: mail all entries with fees To: Alice Smith 2 Leslie Road, Ipswich, MA 01938 (978) 356-5693 E-mail: [email protected] (OPEN TO ALL BREEDS AND MIXED BREEDS) CRDTC dedicates this weekend of trials to JACK HINES in fond and grateful memory of his guidance as an instructor and his kindness as a friend to dogs and humans. OFFICERS President. ........................................................................................................................ Gwen Beaven Vice President .................................................................................................................. Ellen Brinker Treasurer ..................................................................................................................... -

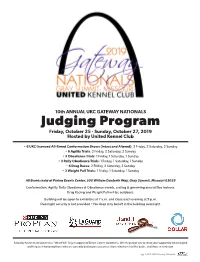

GATEWAY NATIONALS Judging Program Friday, October 25 - Sunday, October 27, 2019 Hosted by United Kennel Club

10th ANNUAL UKC GATEWAY NATIONALS Judging Program Friday, October 25 - Sunday, October 27, 2019 Hosted by United Kennel Club • 6 UKC Licensed All-Breed Conformation Shows (Intact and Altered): 2 Friday, 2 Saturday, 2 Sunday • 6 Agility Trials: 2 Friday, 2 Saturday, 2 Sunday • 3 Obedience Trials: 1 Friday, 1 Saturday, 1 Sunday • 3 Rally Obedience Trials: 1 Friday, 1 Saturday, 1 Sunday • 6 Drag Races: 2 Friday, 2 Saturday, 2 Sunday • 3 Weight Pull Trials: 1 Friday, 1 Saturday, 1 Sunday All Events held at Purina Events Center, 500 William Danforth Way, Gray Summit, Missouri 63039 Conformation, Agility, Rally Obedience & Obedience events, crating & grooming area will be indoors. Drag Racing and Weight Pull will be outdoors. Building will be open to exhibitors at 7 a.m. and close each evening at 9 p.m. Overnight security is not provided • No dogs may be left in the building overnight. Saturday has been designated as “Wear Pink” Day in support of Breast Cancer Awareness. We encourage you to show your support by wearing pink and help us in honoring those who are currently battling breast cancer, those who have lost the battle, and those in remission. pg. 1 2019 UKC Gateway Nationals Sales begin Thursday afternoon! Stop by the UKC Superintendents Table to purchase your GATEWAY MERCHANDISE t-shirts starting at $19 NEW YOUTH Additional T-SHIRT colors and styles will be OPTION available! Items shown are digital mockups of the products for sale. Differences may exist between the mockup and final product. 2019 UKC Gateway Nationals pg. 2 Entry Information • All times are Central Time. -

* PREMIUM LIST * 2 AKC All-Breed Obedience Trials Houston Obedience Training Dog Club, Inc

Obedience Event #’s 2011064617 & 2011064618 Entries Close Wednesday, 6:00 pm, September 28, 2011 After which time entries cannot be accepted, cancelled, altered or substituted except as provided for in Chapter 11, Section 6 of the Dog Show Rules. * PREMIUM LIST * 2 AKC All-Breed Obedience Trials (one ring -- a morning trial, followed by an afternoon trial) Classes offered: Beginner Novice A & B, Novice A & B only Open to all AKC-Recognized Breeds and All American Dogs (Mixed Breeds) Houston Obedience Training Dog Club, Inc. Licensed by the American Kennel Club 2400 Campbell Rd, Unit “H”, Houston, Tx. 77080 Trial Hours: 6:30 a.m. until 30 min. after judging ends Saturday October 15, 2011 All Classes will be held INDOORS, UNBENCHED CERTIFICATION Permission has been granted by the American Kennel Club for the holding of these events under AKC Rules and Regulations. James P. Crowley, Secretary Houston Obedience Training Dog Club, Inc. Trial Secretary Sandra Walroth, 11810 Hammond Dr. Apt 405 Houston, TX 77065 FIRST CLASS MAIL DATED MATERIAL HOUSTON OBEDIENCE DOG TRAINING CLUB, INC. - Non-profit organization for over 40 years - www.hotdogclub.org – 713-694-7446 2400 Campbell Rd., # H, Houston, Tx. 77080 OFFICERS President Kim Hess Vice President Sally Duncan Treasurer Jo Ella Dixon Director Sandy Walroth Secretary Karen Cooper 627 Rolling Mill Dr. Sugarland, Tx 77498 OBEDIENCE TRIAL COMMITTEE Trial Chair: Kathleen Milford 20918 Hamlet Ridge Ln. Katy, Tx 77449 281-796-6189 [email protected] Trial Secretary: Sandy Walroth 11810 Hammond Dr. Apt. 405 Houston, Tx 77065 832-744-0270 [email protected] Chief Ring Steward: Nancy Ward HOT Dog Club Equipment: Kim Hess 2400 Campbell Rd., Unit H Catalog: Cynthia Krohn Grounds: Sandy Magie Houston, TX 77080 Judge’s Hospitality: Donna Fox Ring Setup & Building Prep: George Anna Bobo & Kim Keleman Trial Hospitality: Phyllis Patten & Kathleen Costello www.hotdogclub.org Premium List: Kristi Carpenter Trophy Chair: JoElla Dixon www.facebook.com/hot.dog.club and the Officers and Directors of the HOT Dog Club, Inc. -

On Your Mark

ON YOUR MARK WHAT IS FLYBALL Flyball racing is a fast and exciting sport, not only for the spectators and handlers, but for the dogs as well. There are four dogs on a team with an alternate or two. As teams line up, excitement builds. With each dog eager to compete, sometimes it's all the handler can do to hold their dogs. A judge signals the start of the race between the two competing teams. The first dog from each team is released. Each handler is hoping the green light will go on before their dog hits the start and finish line. The first dog is normally released with the first or second caution light, often more than 50 feet from the start line. Racing side by side, each dog races down its lane, flying over a set of four jumps set ten feet apart. At the far end of each lane is a flyball box. Each dog must step on a flyball box pedal releasing a mechanism flipping a tennis ball from the cup. Like Olympic swimmers, dogs bank off the box, hopefully with the ball, if not, the dog must retrieve the ball, and than return over all four jumps with the ball. As each dog makes the turn another dog is waiting eagerly to be released. Dogs are often released more than 50 feet from the start/finish line in an effort to reach top speed as they pass the returning dog at the start/finish line. The lead changes several times as dogs and handlers alike make mistakes. -

Versatility Award Proposal.Xlsx

VERSATILITY AWARDS Points only received from the top title earned Category A: Conformation (max 5pts) Pts Category E: Agility Pts Bronze GCH - AKC Grand Champion 4 MACH - Master Agility Champion 5 Total Points: /8 CH - AKC Champion 3 MD or MXJ - Master Agility 4 # of Req. Categories: /3 UKC, ARBA, or International Champion 2 AX or AXJ, AGIII - Agility Excellent 4 Novice Title(s): /1 Recommende (Cot 4) - French Evaluation 4 OA or OAH, AGCH - Open Agility 3 Excellent+ - Rating at a Journee or Cotation 3 3 NA or NAH, AGII - Novice Agility 2 Excellent - Rating at a Journee or Cotation 2 2 AGI - Agility I 1 Silver Tres Bon/Bon - Rating at a Journee or Cotation 1 1 Total Points: /12 Category F: Herding Pts # of Req. Categories: /3 Category B: Obedience Pts HC/WTCH/HTCH - Herding Ch./Working Trial Ch./Herding Trial Ch. 5 # of Req. Activites: /4 OTCH - Obedience Trial Champion 5 HX/ATD - Herding Excellent / Advanced Trial Dog 4 Inter./Adv. Title(s): /1 UDX - Utility Dog Excellent 4 HTD-I/II/III - Herding Trial Dog I/II/III 2/3/4 Previous Titles: Bronze UD - Utility Dog 3 HRD-I/II/III - Herding Ranch Dog I/II/III 2/3/4 CDX - Companion Dog Excellent 2 HI/OTD - Herding Intermediate/Open Trial Dog 3 CD - Companion Dog 1 HS/STD - Herding Started/Herding Started 2 Gold BN - Beginner Novice 1 HT/PT/JHD - Herding Tested/Pre-Trial Tested, Junior Herding Dog 1 Total Points: /16 DVG/USA Obedience 1, 2, or 3 1/2/3 # of Req.