2D and 3D Shapes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hydraulic Cylinder Replacement for Cylinders with 3/8” Hydraulic Hose Instructions

HYDRAULIC CYLINDER REPLACEMENT FOR CYLINDERS WITH 3/8” HYDRAULIC HOSE INSTRUCTIONS INSTALLATION TOOLS: INCLUDED HARDWARE: • Knife or Scizzors A. (1) Hydraulic Cylinder • 5/8” Wrench B. (1) Zip-Tie • 1/2” Wrench • 1/2” Socket & Ratchet IMPORTANT: Pressure MUST be relieved from hydraulic system before proceeding. PRESSURE RELIEF STEP 1: Lower the Power-Pole Anchor® down so the Everflex™ spike is touching the ground. WARNING: Do not touch spike with bare hands. STEP 2: Manually push the anchor into closed position, relieving pressure. Manually lower anchor back to the ground. REMOVAL STEP 1: Remove the Cylinder Bottom from the Upper U-Channel using a 1/2” socket & wrench. FIG 1 or 2 NOTE: For Blade models, push bottom of cylinder up into U-Channel and slide it forward past the Ram Spacers to remove it. Upper U-Channel Upper U-Channel Cylinder Bottom 1/2” Tools 1/2” Tools Ram 1/2” Tools Spacers Cylinder Bottom If Ram-Spacers fall out Older models have (1) long & (1) during removal, push short Ram Spacer. Ram Spacers 1/2” Tools bushings in to hold MUST be installed on the same side Figure 1 Figure 2 them in place. they were removed. Blade Models Pro/Spn Models Need help? Contact our Customer Service Team at 1 + 813.689.9932 Option 2 HYDRAULIC CYLINDER REPLACEMENT FOR CYLINDERS WITH 3/8” HYDRAULIC HOSE INSTRUCTIONS STEP 2: Remove the Cylinder Top from the Lower U-Channel using a 1/2” socket & wrench. FIG 3 or 4 Lower U-Channel Lower U-Channel 1/2” Tools 1/2” Tools Cylinder Top Cylinder Top Figure 3 Figure 4 Blade Models Pro/SPN Models STEP 3: Disconnect the UP Hose from the Hydraulic Cylinder Fitting by holding the 1/2” Wrench 5/8” Wrench Cylinder Fitting Base with a 1/2” wrench and turning the Hydraulic Hose Fitting Cylinder Fitting counter-clockwise with a 5/8” wrench. -

Swimming in Spacetime: Motion by Cyclic Changes in Body Shape

RESEARCH ARTICLE tation of the two disks can be accomplished without external torques, for example, by fixing Swimming in Spacetime: Motion the distance between the centers by a rigid circu- lar arc and then contracting a tension wire sym- by Cyclic Changes in Body Shape metrically attached to the outer edge of the two caps. Nevertheless, their contributions to the zˆ Jack Wisdom component of the angular momentum are parallel and add to give a nonzero angular momentum. Cyclic changes in the shape of a quasi-rigid body on a curved manifold can lead Other components of the angular momentum are to net translation and/or rotation of the body. The amount of translation zero. The total angular momentum of the system depends on the intrinsic curvature of the manifold. Presuming spacetime is a is zero, so the angular momentum due to twisting curved manifold as portrayed by general relativity, translation in space can be must be balanced by the angular momentum of accomplished simply by cyclic changes in the shape of a body, without any the motion of the system around the sphere. external forces. A net rotation of the system can be ac- complished by taking the internal configura- The motion of a swimmer at low Reynolds of cyclic changes in their shape. Then, presum- tion of the system through a cycle. A cycle number is determined by the geometry of the ing spacetime is a curved manifold as portrayed may be accomplished by increasing by ⌬ sequence of shapes that the swimmer assumes by general relativity, I show that net translations while holding fixed, then increasing by (1). -

An Introduction to Topology the Classification Theorem for Surfaces by E

An Introduction to Topology An Introduction to Topology The Classification theorem for Surfaces By E. C. Zeeman Introduction. The classification theorem is a beautiful example of geometric topology. Although it was discovered in the last century*, yet it manages to convey the spirit of present day research. The proof that we give here is elementary, and its is hoped more intuitive than that found in most textbooks, but in none the less rigorous. It is designed for readers who have never done any topology before. It is the sort of mathematics that could be taught in schools both to foster geometric intuition, and to counteract the present day alarming tendency to drop geometry. It is profound, and yet preserves a sense of fun. In Appendix 1 we explain how a deeper result can be proved if one has available the more sophisticated tools of analytic topology and algebraic topology. Examples. Before starting the theorem let us look at a few examples of surfaces. In any branch of mathematics it is always a good thing to start with examples, because they are the source of our intuition. All the following pictures are of surfaces in 3-dimensions. In example 1 by the word “sphere” we mean just the surface of the sphere, and not the inside. In fact in all the examples we mean just the surface and not the solid inside. 1. Sphere. 2. Torus (or inner tube). 3. Knotted torus. 4. Sphere with knotted torus bored through it. * Zeeman wrote this article in the mid-twentieth century. 1 An Introduction to Topology 5. -

Volumes of Prisms and Cylinders 625

11-4 11-4 Volumes of Prisms and 11-4 Cylinders 1. Plan Objectives What You’ll Learn Check Skills You’ll Need GO for Help Lessons 1-9 and 10-1 1 To find the volume of a prism 2 To find the volume of • To find the volume of a Find the area of each figure. For answers that are not whole numbers, round to prism a cylinder the nearest tenth. • To find the volume of a 2 Examples cylinder 1. a square with side length 7 cm 49 cm 1 Finding Volume of a 2. a circle with diameter 15 in. 176.7 in.2 . And Why Rectangular Prism 3. a circle with radius 10 mm 314.2 mm2 2 Finding Volume of a To estimate the volume of a 4. a rectangle with length 3 ft and width 1 ft 3 ft2 Triangular Prism backpack, as in Example 4 2 3 Finding Volume of a Cylinder 5. a rectangle with base 14 in. and height 11 in. 154 in. 4 Finding Volume of a 6. a triangle with base 11 cm and height 5 cm 27.5 cm2 Composite Figure 7. an equilateral triangle that is 8 in. on each side 27.7 in.2 New Vocabulary • volume • composite space figure Math Background Integral calculus considers the area under a curve, which leads to computation of volumes of 1 Finding Volume of a Prism solids of revolution. Cavalieri’s Principle is a forerunner of ideas formalized by Newton and Leibniz in calculus. Hands-On Activity: Finding Volume Explore the volume of a prism with unit cubes. -

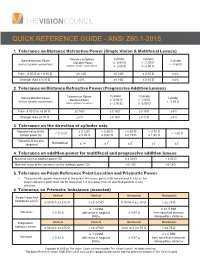

Quick Reference Guide - Ansi Z80.1-2015

QUICK REFERENCE GUIDE - ANSI Z80.1-2015 1. Tolerance on Distance Refractive Power (Single Vision & Multifocal Lenses) Cylinder Cylinder Sphere Meridian Power Tolerance on Sphere Cylinder Meridian Power ≥ 0.00 D > - 2.00 D (minus cylinder convention) > -4.50 D (minus cylinder convention) ≤ -2.00 D ≤ -4.50 D From - 6.50 D to + 6.50 D ± 0.13 D ± 0.13 D ± 0.15 D ± 4% Stronger than ± 6.50 D ± 2% ± 0.13 D ± 0.15 D ± 4% 2. Tolerance on Distance Refractive Power (Progressive Addition Lenses) Cylinder Cylinder Sphere Meridian Power Tolerance on Sphere Cylinder Meridian Power ≥ 0.00 D > - 2.00 D (minus cylinder convention) > -3.50 D (minus cylinder convention) ≤ -2.00 D ≤ -3.50 D From -8.00 D to +8.00 D ± 0.16 D ± 0.16 D ± 0.18 D ± 5% Stronger than ±8.00 D ± 2% ± 0.16 D ± 0.18 D ± 5% 3. Tolerance on the direction of cylinder axis Nominal value of the ≥ 0.12 D > 0.25 D > 0.50 D > 0.75 D < 0.12 D > 1.50 D cylinder power (D) ≤ 0.25 D ≤ 0.50 D ≤ 0.75 D ≤ 1.50 D Tolerance of the axis Not Defined ° ° ° ° ° (degrees) ± 14 ± 7 ± 5 ± 3 ± 2 4. Tolerance on addition power for multifocal and progressive addition lenses Nominal value of addition power (D) ≤ 4.00 D > 4.00 D Nominal value of the tolerance on the addition power (D) ± 0.12 D ± 0.18 D 5. Tolerance on Prism Reference Point Location and Prismatic Power • The prismatic power measured at the prism reference point shall not exceed 0.33Δ or the prism reference point shall not be more than 1.0 mm away from its specified position in any direction. -

Art Concepts for Kids: SHAPE & FORM!

Art Concepts for Kids: SHAPE & FORM! Our online art class explores “shape” and “form” . Shapes are spaces that are created when a line reconnects with itself. Forms are three dimensional and they have length, width and depth. This sweet intro song teaches kids all about shape! Scratch Garden Value Song (all ages) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=coZfbTIzS5I Another great shape jam! https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6hFTUk8XqEc Cookie Monster eats his shapes! https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gfNalVIrdOw&list=PLWrCWNvzT_lpGOvVQCdt7CXL ggL9-xpZj&index=10&t=0s Now for the activities!! Click on the links in the descriptions below for the step by step details. Ages 2-4 Shape Match https://busytoddler.com/2017/01/giant-shape-match-activity/ Shapes are an easy art concept for the littles. Lots of their environment gives play and art opportunities to learn about shape. This Matching activity involves tracing the outside shape of blocks and having littles match the block to the outline. It can be enhanced by letting your little ones color the shapes emphasizing inside and outside the shape lines. Block Print Shapes https://thepinterestedparent.com/2017/08/paul-klee-inspired-block-printing/ Printing is a great technique for young kids to learn. The motion is like stamping so you teach little ones to press and pull rather than rub or paint. This project requires washable paint and paper and block that are not natural wood (which would stain) you want blocks that are painted or sealed. Kids can look at Paul Klee art for inspiration in stacking their shapes into buildings, or they can chose their own design Ages 4-6 Lois Ehlert Shape Animals http://www.momto2poshlildivas.com/2012/09/exploring-shapes-and-colors-with-color.html This great project allows kids to play with shapes to make animals in the style of the artist Lois Ehlert. -

A Three-Dimensional Laguerre Geometry and Its Visualization

A Three-Dimensional Laguerre Geometry and Its Visualization Hans Havlicek and Klaus List, Institut fur¨ Geometrie, TU Wien 3 We describe and visualize the chains of the 3-dimensional chain geometry over the ring R("), " = 0. MSC 2000: 51C05, 53A20. Keywords: chain geometry, Laguerre geometry, affine space, twisted cubic. 1 Introduction The aim of the present paper is to discuss in some detail the Laguerre geometry (cf. [1], [6]) which arises from the 3-dimensional real algebra L := R("), where "3 = 0. This algebra generalizes the algebra of real dual numbers D = R("), where "2 = 0. The Laguerre geometry over D is the geometry on the so-called Blaschke cylinder (Figure 1); the non-degenerate conics on this cylinder are called chains (or cycles, circles). If one generator of the cylinder is removed then the remaining points of the cylinder are in one-one correspon- dence (via a stereographic projection) with the points of the plane of dual numbers, which is an isotropic plane; the chains go over R" to circles and non-isotropic lines. So the point space of the chain geometry over the real dual numbers can be considered as an affine plane with an extra “improper line”. The Laguerre geometry based on L has as point set the projective line P(L) over L. It can be seen as the real affine 3-space on L together with an “improper affine plane”. There is a point model R for this geometry, like the Blaschke cylinder, but it is more compli- cated, and belongs to a 7-dimensional projective space ([6, p. -

1 Lifts of Polytopes

Lecture 5: Lifts of polytopes and non-negative rank CSE 599S: Entropy optimality, Winter 2016 Instructor: James R. Lee Last updated: January 24, 2016 1 Lifts of polytopes 1.1 Polytopes and inequalities Recall that the convex hull of a subset X n is defined by ⊆ conv X λx + 1 λ x0 : x; x0 X; λ 0; 1 : ( ) f ( − ) 2 2 [ ]g A d-dimensional convex polytope P d is the convex hull of a finite set of points in d: ⊆ P conv x1;:::; xk (f g) d for some x1;:::; xk . 2 Every polytope has a dual representation: It is a closed and bounded set defined by a family of linear inequalities P x d : Ax 6 b f 2 g for some matrix A m d. 2 × Let us define a measure of complexity for P: Define γ P to be the smallest number m such that for some C s d ; y s ; A m d ; b m, we have ( ) 2 × 2 2 × 2 P x d : Cx y and Ax 6 b : f 2 g In other words, this is the minimum number of inequalities needed to describe P. If P is full- dimensional, then this is precisely the number of facets of P (a facet is a maximal proper face of P). Thinking of γ P as a measure of complexity makes sense from the point of view of optimization: Interior point( methods) can efficiently optimize linear functions over P (to arbitrary accuracy) in time that is polynomial in γ P . ( ) 1.2 Lifts of polytopes Many simple polytopes require a large number of inequalities to describe. -

Geometry © 2000 Springer-Verlag New York Inc

Discrete Comput Geom OF1–OF15 (2000) Discrete & Computational DOI: 10.1007/s004540010046 Geometry © 2000 Springer-Verlag New York Inc. Convex and Linear Orientations of Polytopal Graphs J. Mihalisin and V. Klee Department of Mathematics, University of Washington, Box 354350, Seattle, WA 98195-4350, USA {mihalisi,klee}@math.washington.edu Abstract. This paper examines directed graphs related to convex polytopes. For each fixed d-polytope and any acyclic orientation of its graph, we prove there exist both convex and concave functions that induce the given orientation. For each combinatorial class of 3-polytopes, we provide a good characterization of the orientations that are induced by an affine function acting on some member of the class. Introduction A graph is d-polytopal if it is isomorphic to the graph G(P) formed by the vertices and edges of some (convex) d-polytope P. As the term is used here, a digraph is d-polytopal if it is isomorphic to a digraph that results when the graph G(P) of some d-polytope P is oriented by means of some affine function on P. 3-Polytopes and their graphs have been objects of research since the time of Euler. The most important result concerning 3-polytopal graphs is the theorem of Steinitz [SR], [Gr1], asserting that a graph is 3-polytopal if and only if it is planar and 3-connected. Also important is the related fact that the combinatorial type (i.e., the entire face-lattice) of a 3-polytope P is determined by the graph G(P). Steinitz’s theorem has been very useful in studying the combinatorial structure of 3-polytopes because it makes it easy to recognize the 3-polytopality of a graph and to construct graphs that represent 3-polytopes without producing an explicit geometric realization. -

Archimedean Solids

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln MAT Exam Expository Papers Math in the Middle Institute Partnership 7-2008 Archimedean Solids Anna Anderson University of Nebraska-Lincoln Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/mathmidexppap Part of the Science and Mathematics Education Commons Anderson, Anna, "Archimedean Solids" (2008). MAT Exam Expository Papers. 4. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/mathmidexppap/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Math in the Middle Institute Partnership at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in MAT Exam Expository Papers by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Archimedean Solids Anna Anderson In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts in Teaching with a Specialization in the Teaching of Middle Level Mathematics in the Department of Mathematics. Jim Lewis, Advisor July 2008 2 Archimedean Solids A polygon is a simple, closed, planar figure with sides formed by joining line segments, where each line segment intersects exactly two others. If all of the sides have the same length and all of the angles are congruent, the polygon is called regular. The sum of the angles of a regular polygon with n sides, where n is 3 or more, is 180° x (n – 2) degrees. If a regular polygon were connected with other regular polygons in three dimensional space, a polyhedron could be created. In geometry, a polyhedron is a three- dimensional solid which consists of a collection of polygons joined at their edges. The word polyhedron is derived from the Greek word poly (many) and the Indo-European term hedron (seat). -

Geometric Modeling in Shape Space

Geometric Modeling in Shape Space Martin Kilian Niloy J. Mitra Helmut Pottmann Vienna University of Technology Figure 1: Geodesic interpolation and extrapolation. The blue input poses of the elephant are geodesically interpolated in an as-isometric- as-possible fashion (shown in green), and the resulting path is geodesically continued (shown in purple) to naturally extend the sequence. No semantic information, segmentation, or knowledge of articulated components is used. Abstract space, line geometry interprets straight lines as points on a quadratic surface [Berger 1987], and the various types of sphere geometries We present a novel framework to treat shapes in the setting of Rie- model spheres as points in higher dimensional space [Cecil 1992]. mannian geometry. Shapes – triangular meshes or more generally Other examples concern kinematic spaces and Lie groups which straight line graphs in Euclidean space – are treated as points in are convenient for handling congruent shapes and motion design. a shape space. We introduce useful Riemannian metrics in this These examples show that it is often beneficial and insightful to space to aid the user in design and modeling tasks, especially to endow the set of objects under consideration with additional struc- explore the space of (approximately) isometric deformations of a ture and to work in more abstract spaces. We will show that many given shape. Much of the work relies on an efficient algorithm to geometry processing tasks can be solved by endowing the set of compute geodesics in shape spaces; to this end, we present a multi- closed orientable surfaces – called shapes henceforth – with a Rie- resolution framework to solve the interpolation problem – which mannian structure. -

Shape Synthesis Notes

SHAPE SYNTHESIS OF HIGH-PERFORMANCE MACHINE PARTS AND JOINTS By John M. Starkey Based on notes from Walter L. Starkey Written 1997 Updated Summer 2010 2 SHAPE SYNTHESIS OF HIGH-PERFORMANCE MACHINE PARTS AND JOINTS Much of the activity that takes place during the design process focuses on analysis of existing parts and existing machinery. There is very little attention focused on the synthesis of parts and joints and certainly there is very little information available in the literature addressing the shape synthesis of parts and joints. The purpose of this document is to provide guidelines for the shape synthesis of high-performance machine parts and of joints. Although these rules represent good design practice for all machinery, they especially apply to high performance machines, which require high strength-to-weight ratios, and machines for which manufacturing cost is not an overriding consideration. Examples will be given throughout this document to illustrate this. Two terms which will be used are part and joint. Part refers to individual components manufactured from a single block of raw material or a single molding. The main body of the part transfers loads between two or more joint areas on the part. A joint is a location on a machine at which two or more parts are fastened together. 1.0 General Synthesis Goals Two primary principles which govern the shape synthesis of a part assert that (1) the size and shape should be chosen to induce a uniform stress or load distribution pattern over as much of the body as possible, and (2) the weight or volume of material used should be a minimum, consistent with cost, manufacturing processes, and other constraints.