A Three-Dimensional Laguerre Geometry and Its Visualization

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Many Lives of the Twisted Cubic

Mathematical Assoc. of America American Mathematical Monthly 121:1 February 10, 2018 11:32 a.m. TwistedMonthly.tex page 1 The many lives of the twisted cubic Abstract. We trace some of the history of the twisted cubic curves in three-dimensional affine and projective spaces. These curves have reappeared many times in many different guises and at different times they have served as primary objects of study, as motivating examples, and as hidden underlying structures for objects considered in mathematics and its applications. 1. INTRODUCTION Because of its simple coordinate functions, the humble (affine) 3 twisted cubic curve in R , given in the parametric form ~x(t) = (t; t2; t3) (1.1) is staple of computational problems in many multivariable calculus courses. (See Fig- ure 1.) We and our students compute its intersections with planes, find its tangent vectors and lines, approximate the arclength of segments of the curve, derive its cur- vature and torsion functions, and so forth. But in many calculus books, the curve is not even identified by name and no indication of its protean nature and rich history is given. This essay is (semi-humorously) in part an attempt to remedy that situation, and (more seriously) in part a meditation on the ways that the things mathematicians study often seem to have existences of their own. Basic structures can reappear at many times in many different contexts and under different names. According to the current consensus view of mathematical historiography, historians of mathematics do well to keep these different avatars of the underlying structure separate because it is almost never correct to attribute our understanding of the sorts of connections we will be con- sidering to the thinkers of the past. -

Hydraulic Cylinder Replacement for Cylinders with 3/8” Hydraulic Hose Instructions

HYDRAULIC CYLINDER REPLACEMENT FOR CYLINDERS WITH 3/8” HYDRAULIC HOSE INSTRUCTIONS INSTALLATION TOOLS: INCLUDED HARDWARE: • Knife or Scizzors A. (1) Hydraulic Cylinder • 5/8” Wrench B. (1) Zip-Tie • 1/2” Wrench • 1/2” Socket & Ratchet IMPORTANT: Pressure MUST be relieved from hydraulic system before proceeding. PRESSURE RELIEF STEP 1: Lower the Power-Pole Anchor® down so the Everflex™ spike is touching the ground. WARNING: Do not touch spike with bare hands. STEP 2: Manually push the anchor into closed position, relieving pressure. Manually lower anchor back to the ground. REMOVAL STEP 1: Remove the Cylinder Bottom from the Upper U-Channel using a 1/2” socket & wrench. FIG 1 or 2 NOTE: For Blade models, push bottom of cylinder up into U-Channel and slide it forward past the Ram Spacers to remove it. Upper U-Channel Upper U-Channel Cylinder Bottom 1/2” Tools 1/2” Tools Ram 1/2” Tools Spacers Cylinder Bottom If Ram-Spacers fall out Older models have (1) long & (1) during removal, push short Ram Spacer. Ram Spacers 1/2” Tools bushings in to hold MUST be installed on the same side Figure 1 Figure 2 them in place. they were removed. Blade Models Pro/Spn Models Need help? Contact our Customer Service Team at 1 + 813.689.9932 Option 2 HYDRAULIC CYLINDER REPLACEMENT FOR CYLINDERS WITH 3/8” HYDRAULIC HOSE INSTRUCTIONS STEP 2: Remove the Cylinder Top from the Lower U-Channel using a 1/2” socket & wrench. FIG 3 or 4 Lower U-Channel Lower U-Channel 1/2” Tools 1/2” Tools Cylinder Top Cylinder Top Figure 3 Figure 4 Blade Models Pro/SPN Models STEP 3: Disconnect the UP Hose from the Hydraulic Cylinder Fitting by holding the 1/2” Wrench 5/8” Wrench Cylinder Fitting Base with a 1/2” wrench and turning the Hydraulic Hose Fitting Cylinder Fitting counter-clockwise with a 5/8” wrench. -

An Introduction to Topology the Classification Theorem for Surfaces by E

An Introduction to Topology An Introduction to Topology The Classification theorem for Surfaces By E. C. Zeeman Introduction. The classification theorem is a beautiful example of geometric topology. Although it was discovered in the last century*, yet it manages to convey the spirit of present day research. The proof that we give here is elementary, and its is hoped more intuitive than that found in most textbooks, but in none the less rigorous. It is designed for readers who have never done any topology before. It is the sort of mathematics that could be taught in schools both to foster geometric intuition, and to counteract the present day alarming tendency to drop geometry. It is profound, and yet preserves a sense of fun. In Appendix 1 we explain how a deeper result can be proved if one has available the more sophisticated tools of analytic topology and algebraic topology. Examples. Before starting the theorem let us look at a few examples of surfaces. In any branch of mathematics it is always a good thing to start with examples, because they are the source of our intuition. All the following pictures are of surfaces in 3-dimensions. In example 1 by the word “sphere” we mean just the surface of the sphere, and not the inside. In fact in all the examples we mean just the surface and not the solid inside. 1. Sphere. 2. Torus (or inner tube). 3. Knotted torus. 4. Sphere with knotted torus bored through it. * Zeeman wrote this article in the mid-twentieth century. 1 An Introduction to Topology 5. -

Volumes of Prisms and Cylinders 625

11-4 11-4 Volumes of Prisms and 11-4 Cylinders 1. Plan Objectives What You’ll Learn Check Skills You’ll Need GO for Help Lessons 1-9 and 10-1 1 To find the volume of a prism 2 To find the volume of • To find the volume of a Find the area of each figure. For answers that are not whole numbers, round to prism a cylinder the nearest tenth. • To find the volume of a 2 Examples cylinder 1. a square with side length 7 cm 49 cm 1 Finding Volume of a 2. a circle with diameter 15 in. 176.7 in.2 . And Why Rectangular Prism 3. a circle with radius 10 mm 314.2 mm2 2 Finding Volume of a To estimate the volume of a 4. a rectangle with length 3 ft and width 1 ft 3 ft2 Triangular Prism backpack, as in Example 4 2 3 Finding Volume of a Cylinder 5. a rectangle with base 14 in. and height 11 in. 154 in. 4 Finding Volume of a 6. a triangle with base 11 cm and height 5 cm 27.5 cm2 Composite Figure 7. an equilateral triangle that is 8 in. on each side 27.7 in.2 New Vocabulary • volume • composite space figure Math Background Integral calculus considers the area under a curve, which leads to computation of volumes of 1 Finding Volume of a Prism solids of revolution. Cavalieri’s Principle is a forerunner of ideas formalized by Newton and Leibniz in calculus. Hands-On Activity: Finding Volume Explore the volume of a prism with unit cubes. -

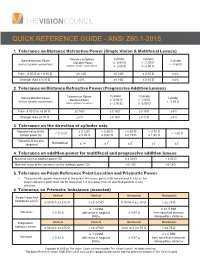

Quick Reference Guide - Ansi Z80.1-2015

QUICK REFERENCE GUIDE - ANSI Z80.1-2015 1. Tolerance on Distance Refractive Power (Single Vision & Multifocal Lenses) Cylinder Cylinder Sphere Meridian Power Tolerance on Sphere Cylinder Meridian Power ≥ 0.00 D > - 2.00 D (minus cylinder convention) > -4.50 D (minus cylinder convention) ≤ -2.00 D ≤ -4.50 D From - 6.50 D to + 6.50 D ± 0.13 D ± 0.13 D ± 0.15 D ± 4% Stronger than ± 6.50 D ± 2% ± 0.13 D ± 0.15 D ± 4% 2. Tolerance on Distance Refractive Power (Progressive Addition Lenses) Cylinder Cylinder Sphere Meridian Power Tolerance on Sphere Cylinder Meridian Power ≥ 0.00 D > - 2.00 D (minus cylinder convention) > -3.50 D (minus cylinder convention) ≤ -2.00 D ≤ -3.50 D From -8.00 D to +8.00 D ± 0.16 D ± 0.16 D ± 0.18 D ± 5% Stronger than ±8.00 D ± 2% ± 0.16 D ± 0.18 D ± 5% 3. Tolerance on the direction of cylinder axis Nominal value of the ≥ 0.12 D > 0.25 D > 0.50 D > 0.75 D < 0.12 D > 1.50 D cylinder power (D) ≤ 0.25 D ≤ 0.50 D ≤ 0.75 D ≤ 1.50 D Tolerance of the axis Not Defined ° ° ° ° ° (degrees) ± 14 ± 7 ± 5 ± 3 ± 2 4. Tolerance on addition power for multifocal and progressive addition lenses Nominal value of addition power (D) ≤ 4.00 D > 4.00 D Nominal value of the tolerance on the addition power (D) ± 0.12 D ± 0.18 D 5. Tolerance on Prism Reference Point Location and Prismatic Power • The prismatic power measured at the prism reference point shall not exceed 0.33Δ or the prism reference point shall not be more than 1.0 mm away from its specified position in any direction. -

![Real Rank Two Geometry Arxiv:1609.09245V3 [Math.AG] 5](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0085/real-rank-two-geometry-arxiv-1609-09245v3-math-ag-5-170085.webp)

Real Rank Two Geometry Arxiv:1609.09245V3 [Math.AG] 5

Real Rank Two Geometry Anna Seigal and Bernd Sturmfels Abstract The real rank two locus of an algebraic variety is the closure of the union of all secant lines spanned by real points. We seek a semi-algebraic description of this set. Its algebraic boundary consists of the tangential variety and the edge variety. Our study of Segre and Veronese varieties yields a characterization of tensors of real rank two. 1 Introduction Low-rank approximation of tensors is a fundamental problem in applied mathematics [3, 6]. We here approach this problem from the perspective of real algebraic geometry. Our goal is to give an exact semi-algebraic description of the set of tensors of real rank two and to characterize its boundary. This complements the results on tensors of non-negative rank two presented in [1], and it offers a generalization to the setting of arbitrary varieties, following [2]. A familiar example is that of 2 × 2 × 2-tensors (xijk) with real entries. Such a tensor lies in the closure of the real rank two tensors if and only if the hyperdeterminant is non-negative: 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 x000x111 + x001x110 + x010x101 + x011x100 + 4x000x011x101x110 + 4x001x010x100x111 −2x000x001x110x111 − 2x000x010x101x111 − 2x000x011x100x111 (1) −2x001x010x101x110 − 2x001x011x100x110 − 2x010x011x100x101 ≥ 0: If this inequality does not hold then the tensor has rank two over C but rank three over R. To understand this example geometrically, consider the Segre variety X = Seg(P1 × P1 × P1), i.e. the set of rank one tensors, regarded as points in the projective space P7 = 2 2 2 7 arXiv:1609.09245v3 [math.AG] 5 Apr 2017 P(C ⊗ C ⊗ C ). -

Hyperbolic Monopoles and Rational Normal Curves

HYPERBOLIC MONOPOLES AND RATIONAL NORMAL CURVES Nigel Hitchin (Oxford) Edinburgh April 20th 2009 204 Research Notes A NOTE ON THE TANGENTS OF A TWISTED CUBIC B Y M. F. ATIYAH Communicated by J. A. TODD Received 8 May 1951 1. Consider a rational normal cubic C3. In the Klein representation of the lines of $3 by points of a quadric Q in Ss, the tangents of C3 are represented by the points of a rational normal quartic O4. It is the object of this note to examine some of the consequences of this correspondence, in terms of the geometry associated with the two curves. 2. C4 lies on a Veronese surface V, which represents the congruence of chords of O3(l). Also C4 determines a 4-space 2 meeting D. in Qx, say; and since the surface of tangents of O3 is a developable, consecutive tangents intersect, and therefore the tangents to C4 lie on Q, and so on £lv Hence Qx, containing the sextic surface of tangents to C4, must be the quadric threefold / associated with C4, i.e. the quadric determining the same polarity as C4 (2). We note also that the tangents to C4 correspond in #3 to the plane pencils with vertices on O3, and lying in the corresponding osculating planes. 3. We shall prove that the surface U, which is the locus of points of intersection of pairs of osculating planes of C4, is the projection of the Veronese surface V from L, the pole of 2, on to 2. Let P denote a point of C3, and t, n the tangent line and osculating plane at P, and let T, T, w denote the same for the corresponding point of C4. -

Natural Cadmium Is Made up of a Number of Isotopes with Different Abundances: Cd106 (1.25%), Cd110 (12.49%), Cd111 (12.8%), Cd

CLASSROOM Natural cadmium is made up of a number of isotopes with different abundances: Cd106 (1.25%), Cd110 (12.49%), Cd111 (12.8%), Cd 112 (24.13%), Cd113 (12.22%), Cd114(28.73%), Cd116 (7.49%). Of these Cd113 is the main neutron absorber; it has an absorption cross section of 2065 barns for thermal neutrons (a barn is equal to 10–24 sq.cm), and the cross section is a measure of the extent of reaction. When Cd113 absorbs a neutron, it forms Cd114 with a prompt release of γ radiation. There is not much energy release in this reaction. Cd114 can again absorb a neutron to form Cd115, but the cross section for this reaction is very small. Cd115 is a β-emitter C V Sundaram, National (with a half-life of 53hrs) and gets transformed to Indium-115 Institute of Advanced Studies, Indian Institute of Science which is a stable isotope. In none of these cases is there any large Campus, Bangalore 560 012, release of energy, nor is there any release of fresh neutrons to India. propagate any chain reaction. Vishwambhar Pati The Möbius Strip Indian Statistical Institute Bangalore 560059, India The Möbius strip is easy enough to construct. Just take a strip of paper and glue its ends after giving it a twist, as shown in Figure 1a. As you might have gathered from popular accounts, this surface, which we shall call M, has no inside or outside. If you started painting one “side” red and the other “side” blue, you would come to a point where blue and red bump into each other. -

10-4 Surface and Lateral Area of Prism and Cylinders.Pdf

Aim: How do we evaluate and solve problems involving surface area of prisms an cylinders? Objective: Learn and apply the formula for the surface area of a prism. Learn and apply the formula for the surface area of a cylinder. Vocabulary: lateral face, lateral edge, right prism, oblique prism, altitude, surface area, lateral surface, axis of a cylinder, right cylinder, oblique cylinder. Prisms and cylinders have 2 congruent parallel bases. A lateral face is not a base. The edges of the base are called base edges. A lateral edge is not an edge of a base. The lateral faces of a right prism are all rectangles. An oblique prism has at least one nonrectangular lateral face. An altitude of a prism or cylinder is a perpendicular segment joining the planes of the bases. The height of a three-dimensional figure is the length of an altitude. Surface area is the total area of all faces and curved surfaces of a three-dimensional figure. The lateral area of a prism is the sum of the areas of the lateral faces. Holt Geometry The net of a right prism can be drawn so that the lateral faces form a rectangle with the same height as the prism. The base of the rectangle is equal to the perimeter of the base of the prism. The surface area of a right rectangular prism with length ℓ, width w, and height h can be written as S = 2ℓw + 2wh + 2ℓh. The surface area formula is only true for right prisms. To find the surface area of an oblique prism, add the areas of the faces. -

Plus Cylinder Lensometry Tara L Bragg, CO August 2015

Mark E Wilkinson, OD Plus Cylinder Lensometry Tara L Bragg, CO August 2015 Lensometry A lensometer is an optical bench consisting of an illuminated moveable target, a powerful fixed lens, and a telescopic eyepiece focused at infinity. The key element is the field lens that is fixed in place so that its focal point is on the back surface of the lens being analyzed. The lensometer measures the back vertex power of the spectacle lens. The vertex power is the reciprocal of the distance between the back surface of the lens and its secondary focal point. This is also known as the back focal length. For this reason, a lensometer does not really measure the true focal length of a lens, which is measured from the principal planes, not from the lens surface. The lensometer works on the Badal principle with the addition of an astronomical telescope for precise detection of parallel rays at neutralization. The Badel principle is Knapp’s law applied to lensometers. Performing Manual Lensometry Focusing the Eyepiece The focus of the lensometer eyepiece must be verified each time the instrument is used, to avoid erroneous readings. 1. With no lens or a plano lens in place on the lensometer, look through the eyepiece of the instrument. Turn the power drum until the mires (the perpendicular cross lines), viewed through the eyepiece, are grossly out of focus. 2. Turn the eyepiece in the plus direction to fog (blur) the target seen through the eyepiece. 3. Slowly turn the eyepiece in the opposite direction until the target is clear, then stop turning. -

ULRICH BUNDLES on CUBIC FOURFOLDS Daniele Faenzi, Yeongrak Kim

ULRICH BUNDLES ON CUBIC FOURFOLDS Daniele Faenzi, Yeongrak Kim To cite this version: Daniele Faenzi, Yeongrak Kim. ULRICH BUNDLES ON CUBIC FOURFOLDS. 2020. hal- 03023101v2 HAL Id: hal-03023101 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03023101v2 Preprint submitted on 25 Nov 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. ULRICH BUNDLES ON CUBIC FOURFOLDS DANIELE FAENZI AND YEONGRAK KIM Abstract. We show the existence of rank 6 Ulrich bundles on a smooth cubic fourfold. First, we construct a simple sheaf E of rank 6 as an elementary modification of an ACM bundle of rank 6 on a smooth cubic fourfold. Such an E appears as an extension of two Lehn-Lehn-Sorger-van Straten sheaves. Then we prove that a general deformation of E(1) becomes Ulrich. In particular, this says that general cubic fourfolds have Ulrich complexity 6. Introduction An Ulrich sheaf on a closed subscheme X of PN of dimension n and degree d is a non-zero coherent sheaf F on X satisfying H∗(X, F(−j)) = 0 for 1 ≤ j ≤ n. In particular, the cohomology table {hi(X, F(j))} of F is a multiple of the cohomology table of Pn. -

![TWO FAMILIES of STABLE BUNDLES with the SAME SPECTRUM Nonreduced [M]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3812/two-families-of-stable-bundles-with-the-same-spectrum-nonreduced-m-953812.webp)

TWO FAMILIES of STABLE BUNDLES with the SAME SPECTRUM Nonreduced [M]

proceedings of the american mathematical society Volume 109, Number 3, July 1990 TWO FAMILIES OF STABLE BUNDLES WITH THE SAME SPECTRUM A. P. RAO (Communicated by Louis J. Ratliff, Jr.) Abstract. We study stable rank two algebraic vector bundles on P and show that the family of bundles with fixed Chern classes and spectrum may have more than one irreducible component. We also produce a component where the generic bundle has a monad with ghost terms which cannot be deformed away. In the last century, Halphen and M. Noether attempted to classify smooth algebraic curves in P . They proceeded with the invariants d , g , the degree and genus, and worked their way up to d = 20. As the invariants grew larger, the number of components of the parameter space grew as well. Recent work of Gruson and Peskine has settled the question of which invariant pairs (d, g) are admissible. For a fixed pair (d, g), the question of determining the number of components of the parameter space is still intractable. For some values of (d, g) (for example [E-l], if d > g + 3) there is only one component. For other values, one may find many components including components which are nonreduced [M]. More recently, similar questions have been asked about algebraic vector bun- dles of rank two on P . We will restrict our attention to stable bundles a? with first Chern class c, = 0 (and second Chern class c2 = n, so that « is a positive integer and i? has no global sections). To study these, we have the invariants n, the a-invariant (which is equal to dim//"'(P , f(-2)) mod 2) and the spectrum.