Taiwanese Director Ang Lee's Creative Trajectory Exemplifies the Growing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Deepen Friendship, Seek Cooperation and Mutual Development

ISSUE 3 2009 NPCNational People’s Congress of China Deepen friendship, seek cooperation and mutual development Chinese Premier’s 60 hours in Copenhagen 3 2 Wang Zhaoguo (first from right), member of Political Bureau of the CPC Central Committee and vice chairman of the NPC Standing Committee, holds a talk with the acting chairman of the National Provincial Affairs Committee of South Africa on November 3rd, 2009. Li Jianmin 3 Contents Special Report Hot Topics Deputy 6 12 20 Deepen friendship, seek Food safety, a long journey Mao Fengmei speaks on his 17 cooperation and mutual ahead of China years of NPC membership development COVER: Low-carbon measures are to be 16 taken during the upcoming Shanghai World 22 Expo 2010. Construction of the China Pavil- NPC oversees how governments An interview with 11th NPC deputy ion was completed on February 8. At the top spend 4 trillion stimulus money of the oriental crown shaped pavilion, four Juma Taier Mawla Hajj solar panels will collect sunlight and turn so- lar energy into electricity inside. CFP 4 NPC Adviser-In-General: Li Jianguo Advisers: Wang Wanbin, Yang Jingyu, Jiang Enzhu, Qiao Xiaoyang, Nan Zhenzhong, Li Zhaoxing Lu Congmin, Wang Yingfan, Ji Peiding, Cao Weizhou Chief of Editorial Board: Li Lianning Members of Editorial Board: Yin Zhongqing, Xin Chunying, Shen Chunyao, Ren Maodong, Zhu Xueqing, Kan Ke, Peng Fang, Wang Tiemin, Yang Ruixue, Gao Qi, Zhao Jie Xu Yan Chief Editor: Wang Tiemin Vice-Chief Editors: Gao Qi, Xu Yan Executive Editor: Xu Yan Copy Editor: Zhang Baoshan, Jiang Zhuqing Layout Designers: Liu Tingting, Chen Yuye Wu Yue General Editorial Office Address: 23 Xijiaominxiang,Xicheng District Beijing 100805,P.R.China Tel: (86-10)6309-8540 (86-10)8308-4419 E-mail: [email protected] ISBN 1674-3008 CN 11-5683/D Price:RMB35 Edited by The People’s Congresses Journal Published by The People’s Congresses Journal Printed by C&C Joint Printing Co.,(Beijing) Ltd. -

Download Heroic Grace: the Chinese Martial Arts Film Catalog (PDF)

UCLA Film and Television Archive Hong Kong Economic and Trade Office in San Francisco HEROIC GRACE: THE CHINESE MARTIAL ARTS FILM February 28 - March 16, 2003 Los Angeles Front and inside cover: Lau Kar-fai (Gordon Liu Jiahui) in THE 36TH CHAMBER OF SHAOLIN (SHAOLIN SANSHILIU FANG ) present HEROIC GRACE: THE CHINESE MARTIAL ARTS FILM February 28 - March 16, 2003 Los Angeles Heroic Grace: The Chinese Martial Arts Film catalog (2003) is a publication of the UCLA Film and Television Archive, Los Angeles, USA. Editors: David Chute (Essay Section) Cheng-Sim Lim (Film Notes & Other Sections) Designer: Anne Coates Printed in Los Angeles by Foundation Press ii CONTENTS From the Presenter Tim Kittleson iv From the Presenting Sponsor Annie Tang v From the Chairman John Woo vi Acknowledgments vii Leaping into the Jiang Hu Cheng-Sim Lim 1 A Note on the Romanization of Chinese 3 ESSAYS Introduction David Chute 5 How to Watch a Martial Arts Movie David Bordwell 9 From Page to Screen: A Brief History of Wuxia Fiction Sam Ho 13 The Book, the Goddess and the Hero: Sexual Bérénice Reynaud 18 Aesthetics in the Chinese Martial Arts Film Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon—Passing Fad Stephen Teo 23 or Global Phenomenon? Selected Bibliography 27 FILM NOTES 31-49 PROGRAM INFORMATION Screening Schedule 51 Print & Tape Sources 52 UCLA Staff 53 iii FROM THE PRESENTER Heroic Grace: The Chinese Martial Arts Film ranks among the most ambitious programs mounted by the UCLA Film and Television Archive, taking five years to organize by our dedicated and intrepid Public Programming staff. -

Martial Arts As Embodied Knowledge: Asian Traditions in a Transnational World

1 Introduction Martial Arts, Transnationalism, and Embodied Knowledge D. S. Farrer and John Whalen-Bridge The outlines of a newly emerging field—martial arts studies—appear in the essays collected here in Martial Arts as Embodied Knowledge: Asian Traditions in a Transnational World. Considering knowledge as “embodied,” where “embodiment is an existential condition in which the body is the subjective source or intersubjective ground of experience,” means under- standing martial arts through cultural and historical experience; these are forms of knowledge characterized as “being-in-the-world” as opposed to abstract conceptions that are somehow supposedly transcendental (Csor- das 1999: 143). Embodiment is understood both as an ineluctable fact of martial training, and as a methodological cue. Assuming at all times that embodied practices are forms of knowledge, the writers of the essays presented in this volume approach diverse cultures through practices that may appear in the West to be esoteric and marginal, if not even dubious and dangerous expressions of those cultures. The body is a chief starting point for each of the enquiries collected in this volume, but embodiment, connecting as it does to imaginative fantasy, psychological patterning, and social organization, extends “far beyond the skin of the practicing individual” (Turner and Yangwen 2009). The discourse of martial arts, which is composed of the sum total of all the ways in which we can register, record, and otherwise signify the experience of martial arts mind- 1 © 2011 State -

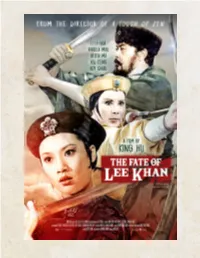

The-Fate-Of-Lee-Khan Presskit.Pdf

presents NEW 2K DIGITAL RESTORATION Hong Kong & Taiwan / 1973 / Action / Mandarin with English Subtitles 106 minutes / 2.35:1 / 5.1 Surround Sound U.S. THEATRICAL PREMIERE Opening April 5th in New York at Metrograph Press Contacts: Michael Krause | Foundry Communications | (212) 586-7967 | [email protected] Michael Lieberman | Metrograph | (212) 660-0312 | [email protected] Film Movement Booking Contacts: Clemence Taillandier | Theatrical | (201) 736-0261 | [email protected] Maxwell Wolkin | Festivals & Non-Theatrical | (212) 941-7744 x211 | [email protected] SYNOPSIS In his follow-up to the critically acclaimed A TOUCH OF ZEN, trailblazing filmmaker King Hu brings together an all-star female cast, including Hong Kong cinema stalwart Li Li-hua and Angela “Lady Kung Fu” Mao, in this lively martial arts adventure. When Lee Khan, a powerful general of the oppressive Yuan Dynasty, procures the battle map of the Chinese rebel army, resistance fighters, aided by an undercover girl-gang, strive to corner him at an inn. Featuring stunning action sequences choreographed by Jackie Chan’s “Kung Fu elder brother” Sammo Hung and a generous mix of intrigue and humor, THE FATE OF LEE KHAN is a legendary wuxia masterpiece. SHORT SYNOPSIS Lee Khan, a powerful general of the oppressive Yuan Dynasty, procures the battle map of the Chinese rebel army. Resistance fighters, aided by an undercover girl-gang, strive to corner him at an inn. LOGLINE King Hu's legendary wuxia masterpiece, starring Li Li-hua, Angela Mao and Hsu Feng. SELECT PRESS “The Fate of Lee Khan is to the Chinese martial arts movie what Once Upon a Time in the West is to the Italian Western: a brilliant anthology of its genre's theme and styles, yielding an exhilaratingly original vision.” –Time Out “The Fate of Lee Khan is a masterclass in getting the maximum from every aspect of production. -

UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT Southern District of New York *SUBJECT to GENERAL and SPECIFIC NOTES to THESE SCHEDULES* SUMMARY

UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT Southern District of New York Refco Capital Markets, LTD Case Number: 05-60018 *SUBJECT TO GENERAL AND SPECIFIC NOTES TO THESE SCHEDULES* SUMMARY OF AMENDED SCHEDULES An asterisk (*) found in schedules herein indicates a change from the Debtor's original Schedules of Assets and Liabilities filed December 30, 2005. Any such change will also be indicated in the "Amended" column of the summary schedules with an "X". Indicate as to each schedule whether that schedule is attached and state the number of pages in each. Report the totals from Schedules A, B, C, D, E, F, I, and J in the boxes provided. Add the amounts from Schedules A and B to determine the total amount of the debtor's assets. Add the amounts from Schedules D, E, and F to determine the total amount of the debtor's liabilities. AMOUNTS SCHEDULED NAME OF SCHEDULE ATTACHED NO. OF SHEETS ASSETS LIABILITIES OTHER YES / NO A - REAL PROPERTY NO 0 $0 B - PERSONAL PROPERTY YES 30 $6,002,376,477 C - PROPERTY CLAIMED AS EXEMPT NO 0 D - CREDITORS HOLDING SECURED CLAIMS YES 2 $79,537,542 E - CREDITORS HOLDING UNSECURED YES 2 $0 PRIORITY CLAIMS F - CREDITORS HOLDING UNSECURED NON- YES 356 $5,366,962,476 PRIORITY CLAIMS G - EXECUTORY CONTRACTS AND UNEXPIRED YES 2 LEASES H - CODEBTORS YES 1 I - CURRENT INCOME OF INDIVIDUAL NO 0 N/A DEBTOR(S) J - CURRENT EXPENDITURES OF INDIVIDUAL NO 0 N/A DEBTOR(S) Total number of sheets of all Schedules 393 Total Assets > $6,002,376,477 $5,446,500,018 Total Liabilities > UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT Southern District of New York Refco Capital Markets, LTD Case Number: 05-60018 GENERAL NOTES PERTAINING TO SCHEDULES AND STATEMENTS FOR ALL DEBTORS On October 17, 2005 (the “Petition Date”), Refco Inc. -

Cultural Control and Globalization in Asia

017.qxd 9/29/2006 2:28 PM Page 1 Batch number: 1 CHECKLIST (must be completed before press) (Please cross through any items that are not applicable) Front board: Spine: Back board: ❑ Title ❑ Title ❑ ISBN ❑ Subtitle ❑ Subtitle ❑ Barcode ❑ Author/edited by ❑ Author/edited by Laikwan Pang IN ASIA AND GLOBALIZATION CONTROL CULTURAL ❑ Series title ❑ Extra logo if required ❑ Extra logo if required Cultural Control and General: ❑ Book size Globalization in Asia ❑ Type fit on spine Copyright, piracy, and cinema CIRCULATED Date: SEEN BY DESK EDITOR: REVISE NEEDED Initial: Date: APPROVED FOR PRESS BY DESK EDITOR Initial: Date: Laikwan Pang ,!7IA4BISBN 978-0-415-35201-7 Routledge Media, Culture and Social Change in Asia www.routledge.com ï an informa business PC4 Royal Demy B-format Spine back edge Laik-FM.qxd 16/11/05 3:15 PM Page i Cultural Control and Globalization in Asia When does inspired creativity become plagiarism? What is the difference between video piracy and free trade? Globalization has made these hot button issues today, and Pang Laikwan’s Cultural Control and Globalization in Asia shows us why. Her analyses of, for example, stylized violence in the production of an Asian cinematic identity and Kill Bill’s copying of it versus attempts to control copying of DVDs of Kill Bill, are vivid and vital reading for anyone who wants to understand the forces shaping contemporary Asian cinematic culture. Chris Berry, Professor of Film and Television Studies, Goldsmiths College, University of London This book makes a valuable contribution to discussions of global film culture. Through an original exploration of the role of “copying” in Asian (and American) cinema, Pang offers us new ways to think about issues ranging from copyright to the relations between global and local cinematic production. -

Mass Internment Camp Implementation, Abuses

CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA ANNUAL REPORT 2020 ONE HUNDRED SIXTEENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION DECEMBER 2020 Printed for the use of the Congressional-Executive Commission on China ( Available via the World Wide Web: https://www.cecc.gov 2020 ANNUAL REPORT CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA ANNUAL REPORT 2020 ONE HUNDRED SIXTEENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION DECEMBER 2020 Printed for the use of the Congressional-Executive Commission on China ( Available via the World Wide Web: https://www.cecc.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 40–674 PDF WASHINGTON : 2020 CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA LEGISLATIVE BRANCH COMMISSIONERS House Senate JAMES P. MCGOVERN, Massachusetts, MARCO RUBIO, Florida, Co-chair Chair JAMES LANKFORD, Oklahoma MARCY KAPTUR, Ohio TOM COTTON, Arkansas THOMAS SUOZZI, New York STEVE DAINES, Montana TOM MALINOWSKI, New Jersey TODD YOUNG, Indiana BEN MCADAMS, Utah DIANNE FEINSTEIN, California CHRISTOPHER SMITH, New Jersey JEFF MERKLEY, Oregon BRIAN MAST, Florida GARY PETERS, Michigan VICKY HARTZLER, Missouri ANGUS KING, Maine EXECUTIVE BRANCH COMMISSIONERS To Be Appointed JONATHAN STIVERS, Staff Director PETER MATTIS, Deputy Staff Director (II) CONTENTS Page Section I. Executive Summary ................................................................................ 1 a. Statement From the Chairs ......................................................................... 1 b. Overview ....................................................................................................... 3 c. Key -

James TIEN 田俊(B

James TIEN 田俊(b. 1942) Actor Born Chen Wen, Tien was from Chao’an, Guangdong. In 1958, he moved to Hong Kong with his family. Same as Angela Mao Ying, he graduated from Fu Hsing Dramatic Arts Academy in Taiwan. He worked as a stuntman at Shaw Brothers in the mid-1960s. In 1969, he gained fame by assisting director Lo Wei in shooting a kung fu movie; soon after, he appeared in Vengeance of a Snow Girl (1971) in which he was also the action choreographer. Tien joined Golden Harvest soon after it was established, and adopted the stage name James Tien since. He was the male lead in the company’s early works, such as The Invincible Eight (1971), The Blade Spares None (1971), The Chase (1971) and Thunderbolt (1973, filmed in 1971). He was also cast in Bruce Lee’s vehicles such as The Big Boss (1971) and Fist of Fury (1972). From A Man Called Tiger (1973) and Seaman No 7 (1973) onward, he was often seen playing the villain; thereafter, he starred in a number of kung fu films, such as Shaolin Boxers (1974), The Dragon Tamers (1975), Hand of Death (1976) and The Shaolin Plot (1977). In 1978, Tien began to work for Lo Wei Motion Picture Co., Ltd., appearing in the Jackie Chan-starring Magnificent Bodyguards (1978), Spiritual Kung Fu (1978) and Dragon Fist (1979), all produced in Taiwan. Tien remained active throughout the 1980s, mostly taking part in Golden Harvest projects, including Winners & Sinners (1983), Twinkle, Twinkle, Lucky Stars (1985), Heart of Dragon (1985), The Millionaires’ Express (1986), Eastern Condors (1987) and Super Lady Cop (1992). -

Annual Report 2019 Annual Report

Annual Report 2019 Annual Report 2019 For more information, please refer to : CONTENTS DEFINITIONS 2 Section I Important Notes 5 Section II Company Profile and Major Financial Information 6 Section III Company Business Overview 18 Section IV Discussion and Analysis on Operation 22 Section V Directors’ Report 61 Section VI Other Significant Events 76 Section VII Changes in Shares and Information on Shareholders 93 Section VIII Directors, Supervisors, Senior Management and Staff 99 Section IX Corporate Governance Report 119 Section X Independent Auditor’s Report 145 Section XI Consolidated Financial Statements 151 Appendix I Information on Securities Branches 276 Appendix II Information on Branch Offices 306 China Galaxy Securities Co., Ltd. Annual Report 2019 1 DEFINITIONS “A Share(s)” domestic shares in the share capital of the Company with a nominal value of RMB1.00 each, which is (are) listed on the SSE, subscribed for and traded in Renminbi “Articles of Association” the articles of association of the Company (as amended from time to time) “Board” or “Board of Directors” the board of Directors of the Company “CG Code” Corporate Governance Code and Corporate Governance Report set out in Appendix 14 to the Stock Exchange Listing Rules “Company”, “we” or “us” China Galaxy Securities Co., Ltd.(中國銀河證券股份有限公司), a joint stock limited company incorporated in the PRC on 26 January 2007, whose H Shares are listed on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange (Stock Code: 06881), the A Shares of which are listed on the SSE (Stock Code: 601881) “Company Law” -

Hong Kong Martial Arts Films

GENDER, IDENTITY AND INFLUENCE: HONG KONG MARTIAL ARTS FILMS Gilbert Gerard Castillo, B.A. Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS December 2002 Approved: Donald E. Staples, Major Professor Harry Benshoff, Committee Member Harold Tanner, Committee Member Ben Levin, Graduate Coordinator of the Department of Radio, TV and Film Alan B. Albarran, Chair of the Department of Radio, TV and Film C. Neal Tate, Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Castillo, Gilbert Gerard, Gender, Identity, and Influence: Hong Kong Martial Arts Films. Master of Arts (Radio, Television and Film), December 2002, 78 pp., references, 64 titles. This project is an examination of the Hong Kong film industry, focusing on the years leading up to the handover of Hong Kong to communist China. The influence of classical Chinese culture on gender representation in martial arts films is examined in order to formulate an understanding of how these films use gender issues to negotiate a sense of cultural identity in the face of unprecedented political change. In particular, the films of Hong Kong action stars Michelle Yeoh and Brigitte Lin are studied within a feminist and cultural studies framework for indications of identity formation through the highlighting of gender issues. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First of all, I would like to thank the members of my committee all of whom gave me valuable suggestions and insights. I would also like to extend a special thank you to Dr. Staples who never failed to give me encouragement and always made me feel like a valuable member of our academic community. -

Forget About the Men, It's Time for the Ladies to Step Into the Spotlight

Forget about the men, it’s time for the ladies to step into the spotlight. Arthur Tam explores the women that have shaped, contributed and kicked major ass in Hong Kong martial arts cinema. Photography by Calvin Sit. Art Direction by Phoebe Cheng. Cover art by Stanley Chung timeout.com.hk 19 o one would argue that Hong Kong, starting with the rise of since much of the genre was shaped by female fighters like Cheng Pei- Shaw Brothers, has dominated martial arts cinema for much pei, Kara Hui, Michelle Yeoh, Angela Mao, Cynthia Rothrock and Yuen Cheng Pei-pei of the last 50 years. Local film makers laid the foundation Qiu. In the 50s and 60s, female lead roles in wuxia and kung fu films 鄭佩佩 for many of the greatest action films ever made, giving rise were just as prevalent as male roles and the ladies threw it down with Nto revered international action heroes like Jet Li, Donnie Yen, Jackie as much strength, speed and tenacity as the men did, if not more. The queen of swords Chan and, of course, the greatest of the greatest, the dragon himself, These day it’s all about fighting to level the playing field and in the Bruce Lee. light of increasing girl power, what better way to celebrate than to Yes, these are the men that we adore to this day, but we forget acknowledge women in an industry that has been so essential to the ’m always up for a fight,” says 70-year- that to their yang there has always been a strong yin.The great popularity of Hong Kong pop culture. -

Statistics on Religions and Churches in the People's Republic of China

Statistics on Religions and Churches in the People’s Republic of China – Update for the Year 2019 Katharina Wenzel-Teuber Translated by Jacqueline Mulberge This year’s statistical update on religions in China focuses on recent results from the China Family Panel Studies. In addition, we present figures on the individual religions from 2019 or – as new figures are not available for each religion every year – from previous years. 1. News from the China Family Panel Studies – “How Many Protestants Are There Really in China?” In an essay published in 2019, based on surveys conducted by the China Family Panel Studies in 2012, 2014 and 2016, the authors arrive at an estimated number of almost 40 million Protestant Christians in China.1 Since their analysis probably contributed signifi- cantly to the very substantial correction and increase in the estimated number of Protes- tants in the China State Council’s White Paper on freedom of religious belief published in 2018 (more on this later), it will be presented in detail below. The “Statistical Update” in Religions & Christianity in Today’s China has reported twice on the China Family Panel Studies (Zhongguo jiating zhuizong diaocha 中国家庭追踪调 查, abbr.: CFPS). The endeavour is a “nationally representative, annual longitudinal sur- vey,” which focuses on the “economic and non-economic well-being of the population.” It is financed by the Chinese government through Peking University. Since 2010, the In- stitute of Social Science Survey of Peking University has regularly surveyed a fixed panel of families and individuals in 25 of the 31 provinces, direct-controlled municipalities and autonomous regions of [Mainland] China, i.e.