Martial Arts As Embodied Knowledge: Asian Traditions in a Transnational World

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aboutdog Brothersmartial Arts

About Dog Brothers Martial Arts Dog Brothers Martial Arts (DBMA) is a system of many styles where the ultimate goal is to “walk as a warrior for all your days™.” As such we have an ap- proach that is in search of the totality of both ritual combat (sport fighting such as Mixed Martial Arts/Vale Tudo, Muay Kickboxing, Brazilian Jiu Jitsu and others) and reality (practical street defense, weapon awareness, and uneven odds). This means that the greater mission is to have real skills throughout the entirety of one’s life—not just when one is young and competitive. Considerable thought and experience has gone into the development of this cur- riculum, and as is the case with all things taught in the DBMA curriculum: “If you see it taught, you see it fought.™” The curriculum is divided into 3 areas: Real Contact Stick Fighting, Kali Tudo™ and Die Less Often. A brief overview of these areas of study is found on the next page. What You’ll Learn Consistency Across Categories Fun, Fit, and Functional Hurting, Healing, and Harmonizing The Filipino Martial Arts are unique in that they As previously stated, we look to share the long In addition to combative tools, tactics, and focus on weapons first, and allow the learning that term training goal: “walk as a warrior for all techniques, DBMA also incorporates a healing takes place there to inform a practitioner’s empty your days™” with you. For the long term, it of component to training. We include yoga, alignment hand movements and skills. -

Download Article

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 278 2nd Yogyakarta International Seminar on Health, Physical Education, and Sport Science (YISHPESS 2018) 1st Conference on Interdisciplinary Approach in Sports (CoIS 2018) Martial art of Dayak Central Kalimantan (a Study of History, Philosophy, and Techniques of Traditional Martial Arts) Eko Hernando Siswantoyo Graduated Program Graduated Program Universitas Negeri Yogyakarta Universitas Negeri Yogyakarta Yogyakarta, Indonesia Yogyakarta, Indonesia [email protected] [email protected] Abstract—This study aims to explore how the history of baboon called as Southern pig-tailed which is called macaca traditional Dayak martial arts in Central Kalimantan, the nemestrina in Latin. philosophy contained therein, and the techniques of martial The bangkui stance is the main or ultimate technique to arts in Dayak Central Kalimantan. The research applied a turn off and lock the opponent's movements because, the qualitative research with historical research method. The Data bangkui movement itself has a some techniques capable of sources in the study were obtained through three traditional paralyzing an opponent with just an attack. This traditional martial arts colleges in Central Kalimantan, namely; martial art tends to use bare hands and relys on the agility of Pangunraun Pitu (East Barito regency), Silat Sakti Salamat the players' movements, although there are also some martial Kambe (Katingan regency), and Palampang Panerus Tinjek art practitioners who use weapons. This pattern of the (Pulang Pisau regency). The data collection techniques used traditional self-defense tends to attack enemies from the were observation, interviews, and documentation. The results showed that (1) the figure who first spread the martial arts of bottom and directly attacks the opponent's body's defensive the Dayak tribe into all parts of Central Kalimantan were two points. -

Download Heroic Grace: the Chinese Martial Arts Film Catalog (PDF)

UCLA Film and Television Archive Hong Kong Economic and Trade Office in San Francisco HEROIC GRACE: THE CHINESE MARTIAL ARTS FILM February 28 - March 16, 2003 Los Angeles Front and inside cover: Lau Kar-fai (Gordon Liu Jiahui) in THE 36TH CHAMBER OF SHAOLIN (SHAOLIN SANSHILIU FANG ) present HEROIC GRACE: THE CHINESE MARTIAL ARTS FILM February 28 - March 16, 2003 Los Angeles Heroic Grace: The Chinese Martial Arts Film catalog (2003) is a publication of the UCLA Film and Television Archive, Los Angeles, USA. Editors: David Chute (Essay Section) Cheng-Sim Lim (Film Notes & Other Sections) Designer: Anne Coates Printed in Los Angeles by Foundation Press ii CONTENTS From the Presenter Tim Kittleson iv From the Presenting Sponsor Annie Tang v From the Chairman John Woo vi Acknowledgments vii Leaping into the Jiang Hu Cheng-Sim Lim 1 A Note on the Romanization of Chinese 3 ESSAYS Introduction David Chute 5 How to Watch a Martial Arts Movie David Bordwell 9 From Page to Screen: A Brief History of Wuxia Fiction Sam Ho 13 The Book, the Goddess and the Hero: Sexual Bérénice Reynaud 18 Aesthetics in the Chinese Martial Arts Film Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon—Passing Fad Stephen Teo 23 or Global Phenomenon? Selected Bibliography 27 FILM NOTES 31-49 PROGRAM INFORMATION Screening Schedule 51 Print & Tape Sources 52 UCLA Staff 53 iii FROM THE PRESENTER Heroic Grace: The Chinese Martial Arts Film ranks among the most ambitious programs mounted by the UCLA Film and Television Archive, taking five years to organize by our dedicated and intrepid Public Programming staff. -

Sag E Arts Unlimited Martial Arts & Fitness Training

Sag e Arts Unlimited Martial Arts & Fitness Training Grappling Intensive Program - Basic Course - Sage Arts Unlimited Grappling Intensive Program - Basic Course Goals for this class: - To introduce and acclimate students to the rigors of Grappling. - To prepare students’ technical arsenal and conceptual understanding of various formats of Grappling. - To develop efficient movement skills and defensive awareness in students. - To introduce students to the techniques of submission wrestling both with and without gi’s. - To introduce students to the striking aspects of Vale Tudo and Shoot Wrestling (Shooto) and their relationship to self-defense, and methods for training these aspects. - To help students begin to think tactically and strategically regarding the opponent’s base, relative position and the opportunities that these create. - To give students a base of effective throws and breakfalls, transitioning from a standing format to a grounded one. Class Rules 1. No Injuries 2. Respect your training partner, when they tap, let up. 3. You are 50% responsible for your safety, tap when it hurts. 4. An open mind is not only encouraged, it is mandatory. 5. Take Notes. 6. No Whining 7. No Ego 8. No Issues. Bring Every Class Optional Equipment Notebook or 3-ring binder for handouts and class notes. Long or Short-sleeved Rashguard Judo or JiuJitsu Gi and Belt Ear Guards T-shirt to train in (nothing too valuable - may get stretched out) Knee Pads Wrestling shoes (optional) Bag Gloves or Vale Tudo Striking Gloves Mouthguard Focus Mitts or Thai Pads Smiling Enthusiasm and Open-mindedness 1 Introduction Grappling Arts from around the World Nearly every culture has its own method of grappling with a unique emphasis of tactic, technique and training mindset. -

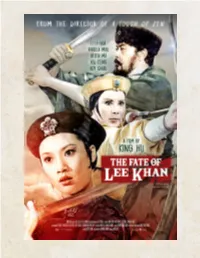

The-Fate-Of-Lee-Khan Presskit.Pdf

presents NEW 2K DIGITAL RESTORATION Hong Kong & Taiwan / 1973 / Action / Mandarin with English Subtitles 106 minutes / 2.35:1 / 5.1 Surround Sound U.S. THEATRICAL PREMIERE Opening April 5th in New York at Metrograph Press Contacts: Michael Krause | Foundry Communications | (212) 586-7967 | [email protected] Michael Lieberman | Metrograph | (212) 660-0312 | [email protected] Film Movement Booking Contacts: Clemence Taillandier | Theatrical | (201) 736-0261 | [email protected] Maxwell Wolkin | Festivals & Non-Theatrical | (212) 941-7744 x211 | [email protected] SYNOPSIS In his follow-up to the critically acclaimed A TOUCH OF ZEN, trailblazing filmmaker King Hu brings together an all-star female cast, including Hong Kong cinema stalwart Li Li-hua and Angela “Lady Kung Fu” Mao, in this lively martial arts adventure. When Lee Khan, a powerful general of the oppressive Yuan Dynasty, procures the battle map of the Chinese rebel army, resistance fighters, aided by an undercover girl-gang, strive to corner him at an inn. Featuring stunning action sequences choreographed by Jackie Chan’s “Kung Fu elder brother” Sammo Hung and a generous mix of intrigue and humor, THE FATE OF LEE KHAN is a legendary wuxia masterpiece. SHORT SYNOPSIS Lee Khan, a powerful general of the oppressive Yuan Dynasty, procures the battle map of the Chinese rebel army. Resistance fighters, aided by an undercover girl-gang, strive to corner him at an inn. LOGLINE King Hu's legendary wuxia masterpiece, starring Li Li-hua, Angela Mao and Hsu Feng. SELECT PRESS “The Fate of Lee Khan is to the Chinese martial arts movie what Once Upon a Time in the West is to the Italian Western: a brilliant anthology of its genre's theme and styles, yielding an exhilaratingly original vision.” –Time Out “The Fate of Lee Khan is a masterclass in getting the maximum from every aspect of production. -

1001 Years of Missing Martial Arts

1001 Years of Missing Martial Arts IMPORTANT NOTICE: Author: Master Mohammed Khamouch Chief Editor: Prof. Mohamed El-Gomati All rights, including copyright, in the content of this document are owned or controlled for these purposes by FSTC Limited. In Deputy Editor: Prof. Mohammed Abattouy accessing these web pages, you agree that you may only download the content for your own personal non-commercial Associate Editor: Dr. Salim Ayduz use. You are not permitted to copy, broadcast, download, store (in any medium), transmit, show or play in public, adapt or Release Date: April 2007 change in any way the content of this document for any other purpose whatsoever without the prior written permission of FSTC Publication ID: 683 Limited. Material may not be copied, reproduced, republished, Copyright: © FSTC Limited, 2007 downloaded, posted, broadcast or transmitted in any way except for your own personal non-commercial home use. Any other use requires the prior written permission of FSTC Limited. You agree not to adapt, alter or create a derivative work from any of the material contained in this document or use it for any other purpose other than for your personal non-commercial use. FSTC Limited has taken all reasonable care to ensure that pages published in this document and on the MuslimHeritage.com Web Site were accurate at the time of publication or last modification. Web sites are by nature experimental or constantly changing. Hence information published may be for test purposes only, may be out of date, or may be the personal opinion of the author. Readers should always verify information with the appropriate references before relying on it. -

The Practice of Pencak Silat in West Java

The Politics of Inner Power: The Practice of Pencak Silat in West Java By Ian Douglas Wilson Ph.D. Thesis School of Asian Studies Murdoch University Western Australia 2002 Declaration This is my own account of the research and contains as its main content, work which has not been submitted for a degree at any university Signed, Ian Douglas Wilson Abstract Pencak silat is a form of martial arts indigenous to the Malay derived ethnic groups that populate mainland and island Southeast Asia. Far from being merely a form of self- defense, pencak silat is a pedagogic method that seeks to embody particular cultural and social ideals within the body of the practitioner. The history, culture and practice of pencak in West Java is the subject of this study. As a form of traditional education, a performance art, a component of ritual and community celebrations, a practical form of self-defense, a path to spiritual enlightenment, and more recently as a national and international sport, pencak silat is in many respects unique. It is both an integrative and diverse cultural practice that articulates a holistic perspective on the world centering upon the importance of the body as a psychosomatic whole. Changing socio-cultural conditions in Indonesia have produced new forms of pencak silat. Increasing government intervention in pencak silat throughout the New Order period has led to the development of nationalized versions that seek to inculcate state-approved values within the body of the practitioner. Pencak silat groups have also been mobilized for the purpose of pursuing political aims. Some practitioners have responded by looking inwards, outlining a path to self-realization framed by the powers, flows and desires found within the body itself. -

Silat: a Muslim Traditional Martial Art in Southern Thailand 125

Silat: A Muslim Traditional Martial Art in Southern Thailand 125 Chapter 3 Silat: A Muslim Traditional Martial Art in Southern Thailand Bussakorn Binson Introduction In Thai nomenclature, silat has various written forms, e.g. zila, sila, shila, zilat, sila, shilat, and zzila. It can also be called dika, buedika, buezila, buerasila, padik, and bueradika. In this chapter, “silat” will be used in accordance with the Encyclopaedia of Cultures in Southern Thailand (Ruengnarong 1999:8029) to depict an art form that is a blend of martial arts, folk performing arts, sport, and an element of the ritual occult all belonging to the Muslim social group of the Malay Peninsula. The most prominent martial art among Thai-Muslim communities in Southern Thailand is known as pencak silat. According to the Pattani Malay dialect - Thai Dictionary, “silat” is derived from “bersila” or “ssila” which means a form of traditional Malaysian martial art. Some linguists postulate that “silat” is derived from the Sanskrit word “shila” which means a fight to support honesty. Silat spread northward from the Malay Peninsula into Southeast Asia sev- eral hundred years ago. Its origin, however, is still ambiguous among Thais due to the absence of written evidence. A few legends have been maintained over the generations by lineages of silat masters in Southern Thailand. Whilst the history of silat is neither clear nor concise, most scholars acknowledge the art form is the result of the blending of a mixture of religious influences from Islam, Hinduism, and Buddhism and cultural influences from Indonesia, India, and China. In this chapter the author will describe the characteristics of silat in Southern Thailand by describing its knowledge transfer and the related rites and beliefs in both practice and performance. -

Silat Martial Ritual Initiation in Brunei Darussalam

Southeast Asia: A Multidisciplinary Journal, Vol 14, 2014, pp 1–13 © FASS, UBD Silat martial ritual initiation in Brunei Darussalam Gabriel Facal Institut de recherches Asiatiques (Aix-Marseille Université) Abstract Almost no research has been done on the silat martial ritual initiations developed in Brunei even though silat continues to be a main cultural marker of the sultanate and it is recurrent in legendary narratives as well as in contemporary local film productions. For Bruneian people, the image of silat is also conveyed by the multitude of Malaysian and Indonesian movies they can watch. Therefore the upheavals that silat has endured since the inception of the sport’s federation in the 1980’s have challenged the possibility of local silat groups keeping alive their practice, structure and organization. These evolutions also reflect certain conflicts in the Bruneian cultural policy, as the government seeks to promote a traditional cultural heritage while at the same time transforming its content to match an alternative ideological discourse. Introduction Martial ritual initiations have spread widely across the so-called Malay world (for debate about this notion, see Barnard, 2004), and have been extensively documented. For example, Maryono (2002) describes pencak and silat in Indonesia, De Grave (2001) deals with pencak in Java, Facal (2012) focuses on penceu in Banten, Wilson (2002) analyzes penca in West Java, and Farrer (2012) considers silat in Malaysia. However, there has been less coverage of the situation in Brunei. This discrepancy can be explained by the secrecy surrounding the transmission and integration of the practice in a wide and complex set of transmission frames, based on an authority structure which refers to local cosmology and religious values. -

Efficacy and Entertainment in Martial Arts Studies D.S. Farrer

Dr. Douglas Farrer is Head of Anthropology at the University CONTRIBUTOR of Guam. He has conducted ethnographic fieldwork in Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand, Hong Kong, and Guam. D. S. Farrer’s research interests include martial arts, the anthropology of performance, visual anthropology, the anthropology of the ocean, digital anthropology, and the sociology of religion. He authored Shadows of the Prophet: Martial Arts and Sufi Mysticism, and co-edited Martial Arts as Embodied Knowledge: Asian Traditions in a Transnational World. Recently Dr. Farrer compiled ‘War Magic and Warrior Religion: Cross-Cultural Investigations’ for Social Analysis. On Guam he is researching Brazilian jiu-jitsu, scuba diving, and Micronesian anthropology. EFFICACY AND ENTERTAINMENT IN MARTIAL ARTS STUDIES anthropological perspectives D.S. FARRER DOI ABSTRACT 10.18573/j.2015.10017 Martial anthropology offers a nomadological approach to Martial Arts Studies featuring Southern Praying Mantis, Hung Sing Choy Li Fut, Yapese stick dance, Chin Woo, Brazilian jiu-jitsu, and seni silat to address the infinity loop model in the anthropology of performance/performance studies which binds KEYWORDs together efficacy and entertainment, ritual and theatre, social and aesthetic drama, concealment and revelation. The infinity Efficacy, entertainment, loop model assumes a positive feedback loop where efficacy nomadology, Brazilian jiu-jitsu, flows into entertainment and vice versa. The problem addressed seni silat, Chinese martial arts, here is what occurs when efficacy and entertainment collide? performance Misframing, captivation, occulturation, and false connections are related as they emerged in anthropological fieldwork settings CITATION from research into martial arts conducted since 2001, where confounded variables may result in new beliefs in the restoration Farrer, D.S. -

Cultural Control and Globalization in Asia

017.qxd 9/29/2006 2:28 PM Page 1 Batch number: 1 CHECKLIST (must be completed before press) (Please cross through any items that are not applicable) Front board: Spine: Back board: ❑ Title ❑ Title ❑ ISBN ❑ Subtitle ❑ Subtitle ❑ Barcode ❑ Author/edited by ❑ Author/edited by Laikwan Pang IN ASIA AND GLOBALIZATION CONTROL CULTURAL ❑ Series title ❑ Extra logo if required ❑ Extra logo if required Cultural Control and General: ❑ Book size Globalization in Asia ❑ Type fit on spine Copyright, piracy, and cinema CIRCULATED Date: SEEN BY DESK EDITOR: REVISE NEEDED Initial: Date: APPROVED FOR PRESS BY DESK EDITOR Initial: Date: Laikwan Pang ,!7IA4BISBN 978-0-415-35201-7 Routledge Media, Culture and Social Change in Asia www.routledge.com ï an informa business PC4 Royal Demy B-format Spine back edge Laik-FM.qxd 16/11/05 3:15 PM Page i Cultural Control and Globalization in Asia When does inspired creativity become plagiarism? What is the difference between video piracy and free trade? Globalization has made these hot button issues today, and Pang Laikwan’s Cultural Control and Globalization in Asia shows us why. Her analyses of, for example, stylized violence in the production of an Asian cinematic identity and Kill Bill’s copying of it versus attempts to control copying of DVDs of Kill Bill, are vivid and vital reading for anyone who wants to understand the forces shaping contemporary Asian cinematic culture. Chris Berry, Professor of Film and Television Studies, Goldsmiths College, University of London This book makes a valuable contribution to discussions of global film culture. Through an original exploration of the role of “copying” in Asian (and American) cinema, Pang offers us new ways to think about issues ranging from copyright to the relations between global and local cinematic production. -

James TIEN 田俊(B

James TIEN 田俊(b. 1942) Actor Born Chen Wen, Tien was from Chao’an, Guangdong. In 1958, he moved to Hong Kong with his family. Same as Angela Mao Ying, he graduated from Fu Hsing Dramatic Arts Academy in Taiwan. He worked as a stuntman at Shaw Brothers in the mid-1960s. In 1969, he gained fame by assisting director Lo Wei in shooting a kung fu movie; soon after, he appeared in Vengeance of a Snow Girl (1971) in which he was also the action choreographer. Tien joined Golden Harvest soon after it was established, and adopted the stage name James Tien since. He was the male lead in the company’s early works, such as The Invincible Eight (1971), The Blade Spares None (1971), The Chase (1971) and Thunderbolt (1973, filmed in 1971). He was also cast in Bruce Lee’s vehicles such as The Big Boss (1971) and Fist of Fury (1972). From A Man Called Tiger (1973) and Seaman No 7 (1973) onward, he was often seen playing the villain; thereafter, he starred in a number of kung fu films, such as Shaolin Boxers (1974), The Dragon Tamers (1975), Hand of Death (1976) and The Shaolin Plot (1977). In 1978, Tien began to work for Lo Wei Motion Picture Co., Ltd., appearing in the Jackie Chan-starring Magnificent Bodyguards (1978), Spiritual Kung Fu (1978) and Dragon Fist (1979), all produced in Taiwan. Tien remained active throughout the 1980s, mostly taking part in Golden Harvest projects, including Winners & Sinners (1983), Twinkle, Twinkle, Lucky Stars (1985), Heart of Dragon (1985), The Millionaires’ Express (1986), Eastern Condors (1987) and Super Lady Cop (1992).