Hong Kong Martial Arts Films

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

See It Big! Action Features More Than 30 Action Movie Favorites on the Big

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE ‘SEE IT BIG! ACTION’ FEATURES MORE THAN 30 ACTION MOVIE FAVORITES ON THE BIG SCREEN April 19–July 7, 2019 Astoria, New York, April 16, 2019—Museum of the Moving Image presents See It Big! Action, a major screening series featuring more than 30 action films, from April 19 through July 7, 2019. Programmed by Curator of Film Eric Hynes and Reverse Shot editors Jeff Reichert and Michael Koresky, the series opens with cinematic swashbucklers and continues with movies from around the world featuring white- knuckle chase sequences and thrilling stuntwork. It highlights work from some of the form's greatest practitioners, including John Woo, Michael Mann, Steven Spielberg, Akira Kurosawa, Kathryn Bigelow, Jackie Chan, and much more. As the curators note, “In a sense, all movies are ’action’ movies; cinema is movement and light, after all. Since nearly the very beginning, spectacle and stunt work have been essential parts of the form. There is nothing quite like watching physical feats, pulse-pounding drama, and epic confrontations on a large screen alongside other astonished moviegoers. See It Big! Action offers up some of our favorites of the genre.” In all, 32 films will be shown, many of them in 35mm prints. Among the highlights are two classic Technicolor swashbucklers, Michael Curtiz’s The Adventures of Robin Hood and Jacques Tourneur’s Anne of the Indies (April 20); Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai (April 21); back-to-back screenings of Mad Max: Fury Road and Aliens on Mother’s Day (May 12); all six Mission: Impossible films -

Empireheads to the Florida Estate of Burt Reynolds To

presents WORDS PORTRAITS Nick de Semlyen Steve Schofi eld EMPIRE HEADS TO THE FLORIDA ESTATE OF BURT REYNOLDS TO SPEND AN ALL-ACCESS WEEKEND WITH THE BANDIT HIMSELF, ONCE THE BIGGEST MOVIE STAR ON THE PLANET TYPE Jordan Metcalf 120 JANUARY 2016 JANUARY 2016 121 Most character-building of all, he shared a New York apartment with Rip Torn. “He was wild,” Reynolds says of the notoriously volatile Men In Black star. “One time they asked me to go duck- hunting in the Roosevelt Game Reserve for (TV show) The American Sportsman, and I took Rip with me. While we were walking around, some geese fl ew above us, squawking. Rip goes, ‘You know what “IF I’D SAID YES TO STAR they’re saying? They’re saying, “That’s the crazy Rip Torn down there.”’ He took his gun, said, ‘I’ll teach that sonuvabitch WARS, IT WOULD HAVE to talk like that,’ and shot one. I said, ‘Rip, you really are crazy.’ But I couldn’t help but love him. Still do.” Reynolds built a reputation as HIS REFRESHMENTS ARE LAID OUT. MEANT NO SMOKEY a fearless man of action, stoked by his A cluster of grapes, a glass of ice water eagerness to do his own stunts. “The and a bowl of Veggie Straws potato fi rst one involved me going through chips (‘Zesty Ranch’ fl avour), arranged AND THE BANDIT…” a plate-glass window on a show called lovingly on a side-table. Frontiers Of Faith,” he says. “I got 125 The students are assembled. This bucks — a nice chunk of change in 1957.” Friday night, 18 of them have come. -

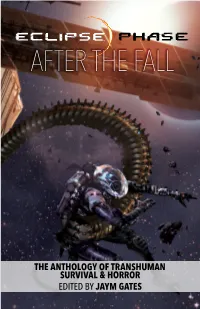

Eclipse Phase: After the Fall

AFTER THE FALL In a world of transhuman survival and horror, technology allows the re-shaping of bodies and minds, but also creates opportunities for oppression and puts the capa- AFTER THE FALL bility for mass destruction in the hands of everyone. Other threats lurk in the devastated habitats of the Fall, dangers both familiar and alien. Featuring: Madeline Ashby Rob Boyle Davidson Cole Nathaniel Dean Jack Graham Georgina Kamsika SURVIVAL &SURVIVAL HORROR Ken Liu OF ANTHOLOGY THE Karin Lowachee TRANSHUMAN Kim May Steven Mohan, Jr. Andrew Penn Romine F. Wesley Schneider Tiffany Trent Fran Wilde ECLIPSE PHASE 21950 Advance THE ANTHOLOGY OF TRANSHUMAN Reading SURVIVAL & HORROR Copy Eclipse Phase created by Posthuman Studios EDITED BY JAYM GATES Eclipse Phase is a trademark of Posthuman Studios LLC. Some content licensed under a Creative Commons License (BY-NC-SA); Some Rights Reserved. © 2016 AFTER THE FALL In a world of transhuman survival and horror, technology allows the re-shaping of bodies and minds, but also creates opportunities for oppression and puts the capa- AFTER THE FALL bility for mass destruction in the hands of everyone. Other threats lurk in the devastated habitats of the Fall, dangers both familiar and alien. Featuring: Madeline Ashby Rob Boyle Davidson Cole Nathaniel Dean Jack Graham Georgina Kamsika SURVIVAL &SURVIVAL HORROR Ken Liu OF ANTHOLOGY THE Karin Lowachee TRANSHUMAN Kim May Steven Mohan, Jr. Andrew Penn Romine F. Wesley Schneider Tiffany Trent Fran Wilde ECLIPSE PHASE 21950 THE ANTHOLOGY OF TRANSHUMAN SURVIVAL & HORROR Eclipse Phase created by Posthuman Studios EDITED BY JAYM GATES Eclipse Phase is a trademark of Posthuman Studios LLC. -

Bullet in the Head

JOHN WOO’S Bullet in the Head Tony Williams Hong Kong University Press The University of Hong Kong Pokfulam Road Hong Kong www.hkupress.org © Tony Williams 2009 ISBN 978-962-209-968-5 All rights reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Printed and bound by Condor Production Ltd., Hong Kong, China Contents Series Preface ix Acknowledgements xiii 1 The Apocalyptic Moment of Bullet in the Head 1 2 Bullet in the Head 23 3 Aftermath 99 Appendix 109 Notes 113 Credits 127 Filmography 129 1 The Apocalyptic Moment of Bullet in the Head Like many Hong Kong films of the 1980s and 90s, John Woo’s Bullet in the Head contains grim forebodings then held by the former colony concerning its return to Mainland China in 1997. Despite the break from Maoism following the fall of the Gang of Four and Deng Xiaoping’s movement towards capitalist modernization, the brutal events of Tiananmen Square caused great concern for a territory facing many changes in the near future. Even before these disturbing events Hong Kong’s imminent return to a motherland with a different dialect and social customs evoked insecurity on the part of a population still remembering the violent events of the Cultural Revolution as well as the Maoist- inspired riots that affected the colony in 1967. -

Gender and the Family in Contemporary Chinese-Language Film Remakes

Gender and the family in contemporary Chinese-language film remakes Sarah Woodland BBusMan., BA (Hons) A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2016 School of Languages and Cultures 1 Abstract This thesis argues that cinematic remakes in the Chinese cultural context are a far more complex phenomenon than adaptive translation between disparate cultures. While early work conducted on French cinema and recent work on Chinese-language remakes by scholars including Li, Chan and Wang focused primarily on issues of intercultural difference, this thesis looks not only at remaking across cultures, but also at intracultural remakes. In doing so, it moves beyond questions of cultural politics, taking full advantage of the unique opportunity provided by remakes to compare and contrast two versions of the same narrative, and investigates more broadly at the many reasons why changes between a source film and remake might occur. Using gender as a lens through which these changes can be observed, this thesis conducts a comparative analysis of two pairs of intercultural and two pairs of intracultural films, each chapter highlighting a different dimension of remakes, and illustrating how changes in gender representations can be reflective not just of differences in attitudes towards gender across cultures, but also of broader concerns relating to culture, genre, auteurism, politics and temporality. The thesis endeavours to investigate the complexities of remaking processes in a Chinese-language cinematic context, with a view to exploring the ways in which remakes might reflect different perspectives on Chinese society more broadly, through their ability to compel the viewer to reflect not only on the past, by virtue of the relationship with a source text, but also on the present, through the way in which the remake reshapes this text to address its audience. -

Spectre, Connoting a Denied That This Was a Reference to the Earlier Films

Key Terms and Consider INTERTEXTUALITY Consider NARRATIVE conventions The white tuxedo intertextually references earlier Bond Behind Bond, image of a man wearing a skeleton mask and films (previous Bonds, including Roger Moore, have worn bone design on his jacket. Skeleton has connotations of Central image, protag- the white tuxedo, however this poster specifically refer- death and danger and the mask is covering up someone’s onist, hero, villain, title, ences Sean Connery in Goldfinger), providing a sense of identity, someone who wishes to remain hidden, someone star appeal, credit block, familiarity, nostalgia and pleasure to fans who recognise lurking in the shadows. It is quite easy to guess that this char- frame, enigma codes, the link. acter would be Propp’s villain and his mask that is reminis- signify, Long shot, facial Bond films have often deliberately referenced earlier films cent of such holidays as Halloween or Day of the Dead means expression, body lan- in the franchise, for example the ‘Bond girl’ emerging he is Bond’s antagonist and no doubt wants to kill him. This guage, colour, enigma from the sea (Ursula Andress in Dr No and Halle Berry in acts as an enigma code for theaudience as we want to find codes. Die Another Day). Daniel Craig also emerged from the sea out who this character is and why he wants Bond. The skele- in Casino Royale, his first outing as Bond, however it was ton also references the title of the film, Spectre, connoting a denied that this was a reference to the earlier films. ghostly, haunting presence from Bond’s past. -

Unbelievable Bodies: Audience Readings of Action Heroines As a Post-Feminist Visual Metaphor

Unbelievable Bodies: Audience Readings of Action Heroines as a Post-Feminist Visual Metaphor Jennifer McClearen A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts University of Washington 2013 Committee: Ralina Joseph, Chair LeiLani Nishime Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Communication ©Copyright 2013 Jennifer McClearen Running head: AUDIENCE READINGS OF ACTION HEROINES University of Washington Abstract Unbelievable Bodies: Audience Readings of Action Heroines as a Post-Feminist Visual Metaphor Jennifer McClearen Chair of Supervisory Committee: Associate Professor Ralina Joseph Department of Communication In this paper, I employ a feminist approach to audience research and examine the individual interviews of 11 undergraduate women who regularly watch and enjoy action heroine films. Participants in the study articulate action heroines as visual metaphors for career and academic success and take pleasure in seeing women succeed against adversity. However, they are reluctant to believe that the female bodies onscreen are physically capable of the action they perform when compared with male counterparts—a belief based on post-feminist assumptions of the limits of female physical abilities and the persistent representations of thin action heroines in film. I argue that post-feminist ideology encourages women to imagine action heroines as successful in intellectual arenas; yet, the ideology simultaneously disciplines action heroine bodies to render them unbelievable as physically powerful women. -

CELEBRITY INTERVIEWS a A1 Aaron Kwok Alessandro Nivola

CELEBRITY INTERVIEWS A A1 Aaron Kwok Alessandro Nivola Alexander Wang Lee Hom Alicia Silverstone Alphaville Andrew Lloyd Webber Andrew Seow Andy Lau Anita Mui Anita Sarawak Ann Kok Anthony Lun Arthur Mendonca B Bananarama Benedict Goh Billy Davis Jr. Boris Becker Boy George Brett Ratner Bruce Beresford Bryan Wong C Candice Yu Casper Van Dien Cass Phang Celine Dion Chow Yun Fat Chris Rock Chris Tucker Christopher Lee Christy Chung Cindy Crawford Cirque du Soleil Coco Lee Conner Reeves Crystals Culture Club Cynthia Koh D Danny Glover David Brown David Julian Hirsh David Morales Denzel Washington Diana Ser Don Cheadle Dick Lee Dwayne Minard E Edward Burns Elijah Wood Elisa Chan Emil Chau Eric Tsang F Fann Wong Faye Wong Flora Chan G George Chaker George Clooney Giovanni Ribisi Glen Goei Gloria Estefan Gordan Chan Gregory Hoblit Gurmit Singh H Halle Berry Hank Azaria Hugh Jackman Hossan Leong I Irene Ang Ix Shen J Jacelyn Tay Jacintha Jackie Chan Jacky Cheung James Ingram James Lye Jamie Lee Jean Reno Jean-Claude van Damme Jeff Chang Jeff Douglas Jeffrey Katzenberg Jennifer Paige Jeremy Davies Jet Li Joan Chen Joe Johnston Joe Pesci Joel Schumacher Joel Silver John Travolta John Woo Johnny Depp Joyce Lee Julian Cheung Julianne Moore K KC Collins Karen Mok Keagan Kang Kenny G Kevin Costner Kim Robinson Kit Chan Koh Chieng Mun Kym Ng L Leelee Sobieski Leon Lai Lim Kay Tong Lisa Ang Lucy Liu M Mariah Carey Mark Richmond Marilyn McCoo Mary Pitilo Matthew Broderick Mel Gibson Mel Smith Michael Chang Mimi Leder Moses Lim N Nadya Hutagalung Nicholas -

Der Teufel Hat Den Schnaps Gemacht...Um Uns Zu Stärken

Repositorium für die Medienwissenschaft Heinz-Jürgen Köhler Der Teufel hat den Schnaps gemacht...um uns zu stärken. Trinken und Kämpfen in Jackie Chans DRUNKEN MASTER-Filmen 2001 https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/110 Veröffentlichungsversion / published version Zeitschriftenartikel / journal article Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Köhler, Heinz-Jürgen: Der Teufel hat den Schnaps gemacht...um uns zu stärken. Trinken und Kämpfen in Jackie Chans DRUNKEN MASTER-Filmen. In: montage AV. Zeitschrift für Theorie und Geschichte audiovisueller Kommunikation, Jg. 10 (2001), Nr. 2, S. 107–114. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/110. Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer Deposit-Lizenz (Keine This document is made available under a Deposit License (No Weiterverbreitung - keine Bearbeitung) zur Verfügung gestellt. Redistribution - no modifications). We grant a non-exclusive, Gewährt wird ein nicht exklusives, nicht übertragbares, non-transferable, individual, and limited right for using this persönliches und beschränktes Recht auf Nutzung dieses document. This document is solely intended for your personal, Dokuments. Dieses Dokument ist ausschließlich für non-commercial use. All copies of this documents must retain den persönlichen, nicht-kommerziellen Gebrauch bestimmt. all copyright information and other information regarding legal Auf sämtlichen Kopien dieses Dokuments müssen alle protection. You are not allowed to alter this document in any Urheberrechtshinweise und sonstigen Hinweise auf gesetzlichen way, to copy it for public or commercial purposes, to exhibit the Schutz beibehalten werden. Sie dürfen dieses Dokument document in public, to perform, distribute, or otherwise use the nicht in irgendeiner Weise abändern, noch dürfen Sie document in public. dieses Dokument für öffentliche oder kommerzielle Zwecke By using this particular document, you accept the conditions of vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, aufführen, vertreiben oder use stated above. -

All the Feff Stars 2017

ALL THE FEFF STARS 2018 Brigitte LIN Ching Hsia, actress, Outside the Window, Cloud of Romance, Red Dust, Dragon Inn, Bride with White Hair, Chungking Express *Golden Mulberry for Lifetime Achievement Award CHINA DING Sheng, director, A Better Tomorrow 2018 ZHANG LinZi, director, Transcendent LIANG Shuang, sound designer, Transcendent FENG Jian, line producer, Transcendent CUI Hongtao, project-in-charge, Transcendent XIN Yukun, director, Wrath of Silence SUN Pei , DJ Pei HONG KONG Nansun SHI, producer Kim ROBINSON, hair-stylist and artist Chapman TO, director, The Empty Hands John SHAM, producer, My Heart is That Eternal Rose Derek CHIU, director, No. 1 Chung Ying Street Johnnie TO, director, producer, Throw Down YEH Ka-lun, director, Fresh Wave: Bright Spring Days HO Chung-ken, director, Fresh Wave: Fires LAM Hei-chun, director, Fresh Wave: Goodbye INDONESIA Arya VASCO, actor, My Generation George TIMOTHY, co-producer, My Generation Emil HERALDI, director, Night Bus JAPAN HIROKI Ryuichi, director, Side Job. TODA Akihiro, director, The Name YOSHIDA Daihachi, director, The Scythian Lamb OOKU Akiko, director, Tremble All You Want UEDA Shinichiro, director, One Cut of the Dead ICHIHASHI Koji, producer, One Cut of the Dead ICHIHARA Hiroshi, actor, One Cut of the Dead OSAWA Sinichiro, actor, One Cut of the Dead SHUHAMA Harumi, actress, One Cut of the Dead TAKEHARA Yoshiko, actress, One Cut of the Dead YOSHIDA Miki, actress, One Cut of the Dead Adam TOREL, representative, One Cut of the Dead TAKAMIYA Eitetsu, DJ THE PHILIPPINES Rae RED, director, -

Introduction

INTRODUCTION The wuxia film is the oldest genre in the Chinese cinema that has remained popular to the present day. Yet despite its longevity, its history has barely been told until fairly recently, as if there was some force denying that it ever existed. Indeed, the genre was as good as non-existent in China, its country of birth, for some fifty years, being proscribed over that time, while in Hong Kong, where it flowered, it was gen- erally derided by critics and largely neglected by film historians. In recent years, it has garnered a following not only among fans but serious scholars. David Bordwell, Zhang Zhen, David Desser and Leon Hunt have treated the wuxia film with the crit- ical respect that it deserves, addressing it in the contexts of larger studies of Hong Kong cinema (Bordwell), the Chinese cinema (Zhang), or the generic martial arts action film and the genre known as kung fu (Desser and Hunt).1 In China, Chen Mo and Jia Leilei have published specific histories, their books sharing the same title, ‘A History of the Chinese Wuxia Film’ , both issued in 2005.2 This book also offers a specific history of the wuxia film, the first in the English language to do so. It covers the evolution and expansion of the genre from its beginnings in the early Chinese cinema based in Shanghai to its transposition to the film industries in Hong Kong and Taiwan and its eventual shift back to the Mainland in its present phase of development. Subject and Terminology Before beginning this history, it is necessary first to settle the question ofterminology , in the process of which, the characteristics of the genre will also be outlined. -

Redirected from Films Considered the Greatest Ever) Page Semi-Protected This List Needs Additional Citations for Verification

List of films considered the best From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia (Redirected from Films considered the greatest ever) Page semi-protected This list needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be chall enged and removed. (November 2008) While there is no general agreement upon the greatest film, many publications an d organizations have tried to determine the films considered the best. Each film listed here has been mentioned in a notable survey, whether a popular poll, or a poll among film reviewers. Many of these sources focus on American films or we re polls of English-speaking film-goers, but those considered the greatest withi n their respective countries are also included here. Many films are widely consi dered among the best ever made, whether they appear at number one on each list o r not. For example, many believe that Orson Welles' Citizen Kane is the best mov ie ever made, and it appears as #1 on AFI's Best Movies list, whereas The Shawsh ank Redemption is #1 on the IMDB Top 250, whilst Star Wars Episode V: The Empire Strikes Back is #1 on the Empire magazine's Top 301 List. None of the surveys that produced these citations should be viewed as a scientif ic measure of the film-watching world. Each may suffer the effects of vote stack ing or skewed demographics. Internet-based surveys have a self-selected audience of unknown participants. The methodology of some surveys may be questionable. S ometimes (as in the case of the American Film Institute) voters were asked to se lect films from a limited list of entries.