PLEASE DO NOT REMOVE THIS PAGE Wu Xia Pian and the Asian Woman Warrior

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The History of Hong Kong Fashion Hong Kong Has Always Had Style

Ven Suite Ad_TIMEOUT HK_201407041.pdf 1 7/4/14 12:42 PM the history of hong kong fashion Hong Kong has always had style. We’ve been channeling the East-meets- West look and making it our own for the last six decades. Arthur Tam travels back in time to revisit and recreate the defining moments of Hong Kong’s fashion history, as C represented by the M most notable female icons of these eras. Y Photography by Calvin Sit. CM Art direction Jeroen Brulez MY CY CMY K ong Kong has a colourful history of fashion. Take a look back through the decades from the 1950s right up to the 1990s, and it’s easy to see a progression and definable change in trends that H reflect shifts in economic prosperity, the influences of myriad foreign cultures, the rise of entertainment and, of course, the power of the consumer zeitgeist. Before China became the manufacturing behemoth that it is today, most of the world looked to Hong Kong for skilled tailors and designers that could develop their brands and labels. For much of the Western world Hong Kong was a gateway into Asia. As cultural mixing began, so did the development of our city’s unique culture and its East-meets-West fashion sensibilities. Taking a trip down memory lane, we can see that Hong Kong has given birth to a variety of fashionable icons who captured the styles and trends of the time. From the 50s, we have the immortal actress Lin Dai, whose youthful and tragic death shocked the city, but as a result solidified her legendary look in intricate, exquisitely tailored and colourful cheongsams. -

Woman As a Category / New Woman Hybridity

COPAS—Current Objectives of Postgraduate American Studies 17.1 (2016) The Heroine and the Meme: Participating in Feminist Discourses Online Svenja Hohenstein ABSTRACT: This article examines the relationship between feminist participatory culture and online activism. I argue that Internet users participate in feminist discourses online by creating memes that present popular fictional female heroes such as Katniss Everdeen (The Hunger Games), Buffy Summers (Buffy the Vampire Slayer), or the Disney Princess Merida (Brave). Emphasizing specific characteristics and plot points of the respective stories, memes project, spread, and celebrate feminist ideas such as female empowerment, agency, and equality. KEYWORDS: Memes, Female Heroes, Online Feminism, Participatory Culture, Katniss Everdeen, Buffy Summers Introduction: Feminisms and Digital Culture Online activists and bloggers use media like memes to transform popular culture into a tool for social change. The result? Young people online are transformed from passive pop culture consumers to engagers and makers. (Martin and Valenti 13) In this article, I take up Courtney Martin and Vanessa Valenti’s claim that producing and sharing Internet memes can be a tool for social change because it enables users to critically participate in social and cultural discourses online. I concentrate on one specific popular culture phenomenon and observe how it is transported online and transformed into memes that contribute to feminist discourses. I focus on fictional female heroes who occupy leading roles in movies and TV-shows and analyze their representation in different types of memes. Katniss Everdeen from the highly successful Hunger Games trilogy can probably be regarded as the best-known representative of this type of character, but she is only one amongst many. -

Archetypes in Literature

Archetypes in Literature Situational, Character and Symbolic What is an archetype? • An archetype is a term used to describe universal symbols that evoke deep and sometimes unconscious responses in a reader • In literature, characters, images, and themes that symbolically embody universal meanings and basic human experiences, regardless of when or where they live, are considered archetypes. Situational Archetype • Situations that occur over and over in different versions of the story. • For example, in versions of Cinderella, a young girl seeks freedom from her current situation. She undergoes some kind of transformation and is better off at the end of the story. Situational- The Quest • Describes the search for someone or something, which when found and brought back will restore balance to the society. Situational- The Task • The task is the superhuman feat must be accomplished in order to fulfill the ultimate goal. Situational- The Journey • The hero is sent in search for some truth of information necessary to restore life, justice, and/or harmony to the kingdom. • The journey includes a series of trials the hero will face along the way. Situational- The Initiation • The initiation refers to the moment, usually psychological, in which the hero comes into maturity. • The hero gains a new awareness into the nature of problems and understands his/ her responsibility for trying to solve the issue. Situational- The Fall • This archetype describes a descent in action from a higher to a lower position in life. • This fall is often accompanied by expulsion from a kind of paradise as a penalty for breaking the rules. Situational- Death and Rebirth • This is the most common of situational archetypes. -

Damsel in Distress Or Princess in Power? Traditional Masculinity and Femininity in Young Adult Novelizations of Cinderella and the Effects on Agency

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 2020-12-09 Damsel in Distress or Princess in Power? Traditional Masculinity and Femininity in Young Adult Novelizations of Cinderella and the Effects on Agency Rylee Carling Brigham Young University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the Education Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Carling, Rylee, "Damsel in Distress or Princess in Power? Traditional Masculinity and Femininity in Young Adult Novelizations of Cinderella and the Effects on Agency" (2020). Theses and Dissertations. 8758. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/8758 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Damsel in Distress or Princess in Power? Traditional Masculinity and Femininity in Young Adult Novelizations of Cinderella and the Effects on Agency Rylee Carling A thesis submitted to the faculty of Brigham Young University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Paul Ricks, Chair Terrell Young Dawan Coombs Stefinee Pinnegar Department of Teacher Education Brigham Young University Copyright © 2020 Rylee Carling All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT Damsel in Distress or Princess in Power? Traditional Masculinity and Femininity in Young Adult Novelizations of Cinderella and the Effects on Agency Rylee Carling Department of Teacher Education, BYU Master of Arts Retellings of classic fairy tales have become increasingly popular in the past decade, but little research has been done on the novelizations written for a young adult (YA) audience. -

Horror Art Exhibit Reflects Past Social Views and Idealisms Ash Comire

Horror art exhibit reflects past social views and idealisms Ash Comire Grotesque creatures. Over-sexualixed women. Fear. A collection of authentic, iconic horror and science fiction all depicting these concepts were the main attraction of Kirk Hammett’s appropriately titled “It’s Alive” at the Columbia Museum of Art. Yes, the Kirk Hammett of influential rock band Metallica had provided the artwork for this exhibit. His collection of horror movie memorabilia takes those who pay the $10 admission back in time to the era of the Great Depression, when horror was not meant to disturb and vomit- induce like today’s measly cash grabs. A plethora of vivid hand-drawn masterpieces meant to intrigue the audiences of the 1930s and 1940s brought a brightness and action to the grim, beastly antagonists of each iconic film, characterizing them in such a way that the movie itself does not even need to be seen. Haunting reds and greys for the infamous Frankenstein invoked enough fear to remind me of when I was six-years-old, hiding my face in my dad’s shoulder at the sight of monsters on film. It was a trip down memory lane for the horror movie fanatic in me contrasted with gorgeous and vintage art that pleased my hipster aesthetic. I made sure to stop at every poster, smiling as names like Karloff and Fonda appeared on posters of movies I grew up watching with my dad and my brother. The older posters of the collection, those whose cast almost always included Karloff, had very distinct, artistic lines, flowing effortlessly to create a colorful rendering of the film’s main social commentary, while the newer ones experimented with photo editing, showcasing the shifting form of art within the theatrical world. -

The Damsel in Distress

THE DAMSEL IN DISTRESS: RESCUING WOMEN FROM AMERICAN MYTHOLOGY By MICHAEL A. SOLIS A capstone submitted to the Graduate School-Camden Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Master of Arts Graduate Program in Liberal Studies Writing under the direction of Dr. Lantzas And approved by _____________________________ Dr. Lantzas Camden, New Jersey December 2016 CAPSTONE ABSTRACT The Damsel in Distress: Rescuing Women from American Mythology By MICHAEL A. SOLIS Capstone Director: Dr. Lantzas Mythology is arguably the most powerful source of influencing and shaping society’s gender roles and beliefs; additionally, mythology provides an accurate reflection of society’s gender roles, general attitudes, fears, and preoccupations. Young boys and girls learn how to negotiate a complex world of possibilities, as well as manage gender expectations through observing gods, superheroes, and other notable characters found in mythological stories. American mythology, to include comic books, the superheroes upon which the literature is based, and the associated cartoons, motion pictures, merchandize, and fashion, contributes to an historical foundation of misogynistic entertainment and serves as didactic material for children and adults. The misogynistic nuances of the comic book storyline are not overt attempts at relegating women; instead, the influence is much more subtle and older than American mythology; rather, this debilitating feature is embedded in our psyche. Although the first comic book was printed in ii 1938, American mythology is largely influenced by Greek mythology, a major influence on western civilization. Overt and subtle misogynistic nuances have always existed in the patriarchal narrative of mythology, American, Greek, and beyond. -

Episode 289 – Talking Sammo Hung | Whistlekickmartialartsradio.Com

Episode 289 – Talking Sammo Hung | whistlekickMartialArtsRadio.com Jeremy Lesniak: Hey there, thanks for tuning in. Welcome, this is whistlekick martial arts radio and today were going to talk all about the man that I believe is the most underrated martial arts actor of today, possibly of all time, Sammo Hung. If you're new to the show you may not know my voice I'm Jeremy Lesniak, I'm the founder of whistlekick we make apparel and sparring gear and training aids and we produce things like this show. I wanna thank you for stopping by, if you want to check out the show notes for this or any of the other episodes we've done, you can find those over at whistlekickmartialartsradio.com. You find our products at whistlekick.com or on Amazon or maybe if you're one of the lucky ones, at your martial arts school because we do offer wholesale accounts. Thank you to everyone who has supported us through purchases and even if you aren’t wearing a whistlekick shirt or something like that right now, thank you for taking the time out of your day to listen to this episode. As I said, here on today's episode, were talking about one of the most respected martial arts actor still working today, a man who has been active in the film industry for almost 60 years. None other the Sammo Hung. Also known as Hung Kam Bow i'll admit my pronunciation is not always the best I'm doing what I can. Hung originates from Hong Kong where he is known not only as an actor but also as an action choreographer, producer, and director. -

Download Heroic Grace: the Chinese Martial Arts Film Catalog (PDF)

UCLA Film and Television Archive Hong Kong Economic and Trade Office in San Francisco HEROIC GRACE: THE CHINESE MARTIAL ARTS FILM February 28 - March 16, 2003 Los Angeles Front and inside cover: Lau Kar-fai (Gordon Liu Jiahui) in THE 36TH CHAMBER OF SHAOLIN (SHAOLIN SANSHILIU FANG ) present HEROIC GRACE: THE CHINESE MARTIAL ARTS FILM February 28 - March 16, 2003 Los Angeles Heroic Grace: The Chinese Martial Arts Film catalog (2003) is a publication of the UCLA Film and Television Archive, Los Angeles, USA. Editors: David Chute (Essay Section) Cheng-Sim Lim (Film Notes & Other Sections) Designer: Anne Coates Printed in Los Angeles by Foundation Press ii CONTENTS From the Presenter Tim Kittleson iv From the Presenting Sponsor Annie Tang v From the Chairman John Woo vi Acknowledgments vii Leaping into the Jiang Hu Cheng-Sim Lim 1 A Note on the Romanization of Chinese 3 ESSAYS Introduction David Chute 5 How to Watch a Martial Arts Movie David Bordwell 9 From Page to Screen: A Brief History of Wuxia Fiction Sam Ho 13 The Book, the Goddess and the Hero: Sexual Bérénice Reynaud 18 Aesthetics in the Chinese Martial Arts Film Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon—Passing Fad Stephen Teo 23 or Global Phenomenon? Selected Bibliography 27 FILM NOTES 31-49 PROGRAM INFORMATION Screening Schedule 51 Print & Tape Sources 52 UCLA Staff 53 iii FROM THE PRESENTER Heroic Grace: The Chinese Martial Arts Film ranks among the most ambitious programs mounted by the UCLA Film and Television Archive, taking five years to organize by our dedicated and intrepid Public Programming staff. -

Aspects of Chinese Cinema Today

Aspects of Chinese Cinema Today By Toh, Hai Leong Spring 1997 Issue of KINEMA 1. THE TAIWANESE ANTONIONI: TSAI MING-LIANG’S DISPLACEMENT OF LOVE IN AN URBAN ENVIRONMENT NO, Tsai Ming-liang is not in fact Taiwanese. The bespectacled 40-year-old bachelor was born in Kuching, Sarawak (East Malaysia) and only came to Taiwan for a college education. After graduating with a degree in drama and film in Taiwan’s University, he settled there and impressed critics with several experimental plays and television movies such as Give Me A Home (1988), The Happy Weaver(1989), My Name is Mary (1990), Ah Hsiung’s First Love(1990). He made a brilliant film debut in 1992 with Rebels Of The Neon God and his film Vive l’amour shared Venice’s Golden Lion for Best Film with Milcho Manchevski’s Before The Rain (1994). Rebels of the Neon God, a film about aimless and nihilistic Taipei youths, won numerous awards abroad: Among them, the Best Film award at the Festival International Cinema Giovani (1993), Best Film of New Director Award of Torino Film Festival (1993), the Best Music Award, Grand Prize and Best Director Awards of Taiwan Golden Horse Festival (1992), the Best Film of Chinese Film Festival (1992), a bronze award at the Tokyo International Film Festival in 1993 and the Best Director Award and Leading Actor Award at the Nantes Festival des Trois Continents in 1994.(1) For the sake of simplicity, he will be referred to as ”Taiwanese”, since he has made Taipei, (Taiwan) his home. In fact, he is considered to be among the second generation of New Wave filmmakers in Taiwan. -

Martial Arts As Embodied Knowledge: Asian Traditions in a Transnational World

1 Introduction Martial Arts, Transnationalism, and Embodied Knowledge D. S. Farrer and John Whalen-Bridge The outlines of a newly emerging field—martial arts studies—appear in the essays collected here in Martial Arts as Embodied Knowledge: Asian Traditions in a Transnational World. Considering knowledge as “embodied,” where “embodiment is an existential condition in which the body is the subjective source or intersubjective ground of experience,” means under- standing martial arts through cultural and historical experience; these are forms of knowledge characterized as “being-in-the-world” as opposed to abstract conceptions that are somehow supposedly transcendental (Csor- das 1999: 143). Embodiment is understood both as an ineluctable fact of martial training, and as a methodological cue. Assuming at all times that embodied practices are forms of knowledge, the writers of the essays presented in this volume approach diverse cultures through practices that may appear in the West to be esoteric and marginal, if not even dubious and dangerous expressions of those cultures. The body is a chief starting point for each of the enquiries collected in this volume, but embodiment, connecting as it does to imaginative fantasy, psychological patterning, and social organization, extends “far beyond the skin of the practicing individual” (Turner and Yangwen 2009). The discourse of martial arts, which is composed of the sum total of all the ways in which we can register, record, and otherwise signify the experience of martial arts mind- 1 © 2011 State -

The-Fate-Of-Lee-Khan Presskit.Pdf

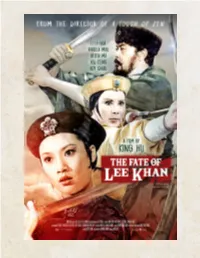

presents NEW 2K DIGITAL RESTORATION Hong Kong & Taiwan / 1973 / Action / Mandarin with English Subtitles 106 minutes / 2.35:1 / 5.1 Surround Sound U.S. THEATRICAL PREMIERE Opening April 5th in New York at Metrograph Press Contacts: Michael Krause | Foundry Communications | (212) 586-7967 | [email protected] Michael Lieberman | Metrograph | (212) 660-0312 | [email protected] Film Movement Booking Contacts: Clemence Taillandier | Theatrical | (201) 736-0261 | [email protected] Maxwell Wolkin | Festivals & Non-Theatrical | (212) 941-7744 x211 | [email protected] SYNOPSIS In his follow-up to the critically acclaimed A TOUCH OF ZEN, trailblazing filmmaker King Hu brings together an all-star female cast, including Hong Kong cinema stalwart Li Li-hua and Angela “Lady Kung Fu” Mao, in this lively martial arts adventure. When Lee Khan, a powerful general of the oppressive Yuan Dynasty, procures the battle map of the Chinese rebel army, resistance fighters, aided by an undercover girl-gang, strive to corner him at an inn. Featuring stunning action sequences choreographed by Jackie Chan’s “Kung Fu elder brother” Sammo Hung and a generous mix of intrigue and humor, THE FATE OF LEE KHAN is a legendary wuxia masterpiece. SHORT SYNOPSIS Lee Khan, a powerful general of the oppressive Yuan Dynasty, procures the battle map of the Chinese rebel army. Resistance fighters, aided by an undercover girl-gang, strive to corner him at an inn. LOGLINE King Hu's legendary wuxia masterpiece, starring Li Li-hua, Angela Mao and Hsu Feng. SELECT PRESS “The Fate of Lee Khan is to the Chinese martial arts movie what Once Upon a Time in the West is to the Italian Western: a brilliant anthology of its genre's theme and styles, yielding an exhilaratingly original vision.” –Time Out “The Fate of Lee Khan is a masterclass in getting the maximum from every aspect of production. -

Martial Arts Cinema and Hong Kong Modernity

Martial Arts Cinema and Hong Kong Modernity Aesthetics, Representation, Circulation Man-Fung Yip Hong Kong University Press Th e University of Hong Kong Pokfulam Road Hong Kong www.hkupress.org © 2017 Hong Kong University Press ISBN 978-988-8390-71-7 (Hardback) All rights reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any infor- mation storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. An earlier version of Chapter 2 “In the Realm of the Senses” was published as “In the Realm of the Senses: Sensory Realism, Speed, and Hong Kong Martial Arts Cinema,” Cinema Journal 53 (4): 76–97. Copyright © 2014 by the University of Texas Press. All rights reserved. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Printed and bound by Paramount Printing Co., Ltd. in Hong Kong, China Contents Acknowledgments viii Notes on Transliteration x Introduction: Martial Arts Cinema and Hong Kong Modernity 1 1. Body Semiotics 24 2. In the Realm of the Senses 56 3. Myth and Masculinity 85 4. Th e Diffi culty of Diff erence 115 5. Marginal Cinema, Minor Transnationalism 145 Epilogue 186 Filmography 197 Bibliography 203 Index 215 Introduction Martial Arts Cinema and Hong Kong Modernity Made at a time when confi dence was dwindling in Hong Kong due to a battered economy and in the aft ermath of the SARS epidemic outbreak,1 Kung Fu Hustle (Gongfu, 2004), the highly acclaimed action comedy by Stephen Chow, can be seen as an attempt to revitalize the positive energy and tenacious resolve—what is commonly referred to as the “Hong Kong spirit” (Xianggang jingshen)—that has allegedly pro- pelled the city’s amazing socioeconomic growth.