The Brandeis Fifth-Century Athenian Lekythos Evolution of Form, Ritual Practices and Use

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ancient Greek Vessels Pattern and Image

ANCIENT GREEK VESSELS PATTERN AND IMAGE 1 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS It is my pleasure to acknowledge the many individuals who helped make this exhibition possible. As the first collaboration between The Trout Gallery at Dickinson College and Bryn Mawr and Wilson Colleges, we hope that this exhibition sets a precedent of excellence and substance for future collaborations of this sort. At Wilson College, Robert K. Dickson, Associate Professor of Fine Art and Leigh Rupinski, College Archivist, enthusiasti- cally supported loaning the ancient Cypriot vessels seen here from the Barron Blewett Hunnicutt Classics ANCIENT Gallery/Collection. Emily Stanton, an Art History Major, Wilson ’15, prepared all of the vessels for our initial selection and compiled all existing documentation on them. At Bryn Mawr, Brian Wallace, Curator and Academic Liaison for Art and Artifacts, went out of his way to accommodate our request to borrow several ancient Greek GREEK VESSELS vessels at the same time that they were organizing their own exhibition of works from the same collection. Marianne Weldon, Collections Manager for Special Collections, deserves special thanks for not only preparing PATTERN AND IMAGE the objects for us to study and select, but also for providing images, procuring new images, seeing to the docu- mentation and transport of the works from Bryn Mawr to Carlisle, and for assisting with the installation. She has been meticulous in overseeing all issues related to the loan and exhibition, for which we are grateful. At The Trout Gallery, Phil Earenfight, Director and Associate Professor of Art History, has supported every idea and With works from the initiative that we have proposed with enthusiasm and financial assistance, without which this exhibition would not have materialized. -

About a Type of Islamic Incense Burner 29

ABOUT A TYPE OF ISLAMIC INCENSE BURNER MEHMET AGA-OGLU NCENSE burners were no novel vessels produced to usheredinto a chamberand served a meal, after which the meet the specific needs of Islamic social life. The ori- incense burnerswere brought so that the guests could per- gin of thurification with various aromatic substances fume themselves before entering the caliph's presence.5 for magical, religious, or social occasions,and the devising The amount of aromatic substances,particularly aloes and of special vessels for the purpose,go far back to the histori- certain varieties of sandalwoods, used for thurification in cal beginnings of the Near Eastern peoples.1 Islam, al- the households of caliphs and dignitaries, must have been though in principle opposed to luxurious ways of life, did enormous. We are informed by al-Tabari, for example, not prevent the use of incense and perfumes. The popu- that Amr ibn al-Laith, the founder of the Saffarid dynasty larity of perfumes during the first centuries is best illus- of Eastern Iran, sent to Caliphal-Mu'tamid in the year 268 trated by the lengthy legistic opinions expressed in the (881/82) 200 minas of aloes wood which he had confis- Hadith literature,2and, among others, by a chapter in the cated from a grandson of Abu Dulaf.6 Among the proper- manual for elegant manners "of a man of polite education," ties left after his death in 301 (913), by Abu'l-Husayn written by Abu'l-Tayyib Muhammad ibn Ishaq al-Wash- Ali ibn Ahmad al-Rasibi, the 'Abbasid governor of Khu- sha.' zistan and neighboring territories,were great numbers of Historicalsources are extremely generous with accounts gold and silver vessels, perfumes, and other valuables, as on the subject.' A few examples can be cited here, and well as 4,420 mithkals of aloes wood for thurification.7 others will be presentedelsewhere. -

Greek Pottery Gallery Activity

SMART KIDS Greek Pottery The ancient Greeks were Greek pottery comes in many excellent pot-makers. Clay different shapes and sizes. was easy to find, and when This is because the vessels it was fired in a kiln, or hot were used for different oven, it became very strong. purposes; some were used for They decorated pottery with transportation and storage, scenes from stories as well some were for mixing, eating, as everyday life. Historians or drinking. Below are some have been able to learn a of the most common shapes. great deal about what life See if you can find examples was like in ancient Greece by of each of them in the gallery. studying the scenes painted on these vessels. Greek, Attic, in the manner of the Berlin Painter. Panathenaic amphora, ca. 500–490 B.C. Ceramic. Bequest of Mrs. Allan Marquand (y1950-10). Photo: Bruce M. White Amphora Hydria The name of this three-handled The amphora was a large, two- vase comes from the Greek word handled, oval-shaped vase with for water. Hydriai were used for a narrow neck. It was used for drawing water and also as urns storage and transport. to hold the ashes of the dead. Krater Oinochoe The word krater means “mixing The Oinochoe was a small pitcher bowl.” This large, two-handled used for pouring wine from a krater vase with a broad body and wide into a drinking cup. The word mouth was used for mixing wine oinochoe means “wine-pourer.” with water. Kylix Lekythos This narrow-necked vase with The kylix was a drinking cup with one handle usually held olive a broad, relatively shallow body. -

Bijildings on the West Side of the Ag-Ora

BIJILDINGS ON THE WEST SIDE OF THE AG-ORA PLATES I-VITI INTRODUCTION' The region to the north of the Areopagus and to the east of Kolonos Agoraios had many natural advantages to recommend it as the site for thZecentral public place of the com- munity (Fig. 1). It was the most open and level area of any extent beneath the immediate shelter of the Acropolis. Along its southern edge a series of springs bubbled out from the foot of the Areopagus, so abundant as to have formed the principal source of drinking water in the city throughout antiquity. A gentle slope toward the north guaranteed adequate natural drainage, desirable for private habitation and essential for the construc- tion of large public buildings. The region lay, moreover, on the direct route between the Acropolis and the Dipylon, the principal gate of the city, and so was conveniently situated alike for residents and visitors. Actual habitation in the area can now be shown to extend at least well back into the second millennium B.C. Scattered fragments of household pottery of typical Middle Helladic types, Gray Minyan and Matt-painted wares, have appeared above bedrock along the north foot of the Areopagus, along the east slope and foot of Kolonos and even at the north foot of Kolonos. A simple shaft burial not later than this period was made near the mid point of the east foot of the latter hill 2 (Fig. 64, Section C-C). Practically no house- hold pottery of Late Helladic times has been found in the area so that there is no direct evidence for habitation in this period. -

Catalogue 8 Autumn 2020

catalogue 8 14-16 Davies Street london W1K 3DR telephone +44 (0)20 7493 0806 e-mail [email protected] WWW.KalloSgalleRy.com 1 | A EUROPEAN BRONZE DIRK BLADE miDDle BRonze age, ciRca 1500–1100 Bc length: 13.9 cm e short sword is thought to be of english origin. e still sharp blade is ogival in form and of rib and groove section. in its complete state the blade would have been completed by a grip, and secured to it by bronze rivets. is example still preserves one of the original rivets at the butt. is is a rare form, with wide channels and the midrib extending virtually to the tip. PRoVenance Reputedly english With H.a. cahn (1915–2002) Basel, 1970s–90s With gallery cahn, prior to 2010 Private collection, Switzerland liteRatuRe Dirks are short swords, designed to be wielded easily with one hand as a stabbing weapon. For a related but slightly earlier in date dagger or dirk with the hilt still preserved, see British museum: acc. no. 1882,0518.6, which was found in the River ames. For further discussion of the type, cf. J. evans, e Ancient Bronze Implements, Weapons and Ornaments of Great Britain and Ireland, london, 1881; S. gerloff and c.B. Burgess, e Dirks and Rapiers of Great Britain and Ireland, abteilung iV: Band 7, munich, Beck, 1981. 4 5 2 | TWO GREEK BRONZE PENDANT BIRD)HEAD PYXIDES PRoVenance christie’s, london, 14 may 2002, lot 153 american private collection geometRic PeRioD, ciRca 10tH–8tH centuRy Bc Heights: 9.5 cm; 8 cm liteRatuRe From northern greece, these geometric lidded pendant pyxides are called a ‘sickle’ type, one with a broad tapering globular body set on a narrow foot that flares at the base; the other and were most likely used to hold perfumed oils or precious objects. -

A Prize Aryballos

A PRIZE ARYBALLOS (PLATES 63 AND 64) T nHE most interesting single find from the excavation of 1954 on Temple Hill in Corinth was the fine aryballos of Middle Corinthian date with a representationof a dancing chorus (see above, pp. 151-152). Its significance is readily apparent: in it are combbinedneat and very careful workmanship,a fresh and lively scene, which is one of the earliest representations of a dancing chorus, and one of the longest archaic Corinthian inscriptions, other than a list of names, yet discovered on a vase (PIs. 63, 64). The subject of the scene and the inscription imply that this was not an ordin- ary product of the potter's workshop, but a special order, made as a prize, or in com- memoration of a vrictoryin a dancing contest, and dedicated by the chorus leader, Pyrvias (Pyrrhias). It is a vase worthy of a place in the early archaic temple in spite of its small size,' for every element of its decoration shows great care and the scene, with its youthful chorus and leader, is no comast dance, but a serious and proper performance, gracefully and simply executed. The vase is complete except for a piece of the front part of the lip, conveniently broken in antiquity to reveal the scene better to its modern viewers. It shows no signs of actual use, but is worn slightly on the sides and back of the handle by abrasion from the rough filling in which it lay. The clay is a typical Corinthian buff, the surface smooth and polished. -

Attic Pottery of the Later Fifth Century from the Athenian Agora

ATTIC POTTERY OF THE LATER FIFTH CENTURY FROM THE ATHENIAN AGORA (PLATES 73-103) THE 1937 campaign of the American excavations in the Athenian Agora included work on the Kolonos Agoraios. One of the most interesting results was the discovery and clearing of a well 1 whose contents proved to be of considerable value for the study of Attic pottery. For this reason it has seemed desirable to present the material as a whole.2 The well is situated on the southern slopes of the Kolonos. The diameter of the shaft at the mouth is 1.14 metres; it was cleared to the bottom, 17.80 metres below the surface. The modern water-level is 11 metres down. I quote the description from the excavator's notebook: The well-shaft, unusually wide and rather well cut widens towards the bottom to a diameter of ca. 1.50 m. There were great quantities of pot- tery, mostly coarse; this pottery seems to be all of the same period . and joins In addition to the normal abbreviations for periodicals the following are used: A.B.C. A n tiquites du Bosphore Cimmerien. Anz. ArchaiologischerAnzeiger. Deubner Deubner, Attische Feste. FR. Furtwangler-Reichhold, Griechische Vasenmxlerei. Kekule Kekule, Die Reliefs an der Balustrade der Athena Nike. Kraiker Kraiker,Die rotfigurigenattischen Vasen (Collectionof the ArchaeologicalIn- stitute of Heidelberg). Langlotz Langlotz, Griechische Vasen in Wiirzburg. ML. Monumenti Antichi Pu'bblicatiper Cura della Reale Accadenia dei Lincei. Rendiconti Rendiconti della Reale Accademia dei Lincei. Richter and Hall Richter and Hall, Red-Figured Athenian Vases in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. -

A Protocorinthian Aryballos with a Myth Scene from Tegea

SVENSKA INSTITUTEN I ATHEN OCH ROM INSTITUTUM ATHENIENSE ATQUE INSTITUTUM ROMANUM REGNI SUECIAE Opuscula Annual of the Swedish Institutes at Athens and Rome 13 2020 STOCKHOLM Licensed to <[email protected]> EDITORIAL COMMITTEE Prof. Gunnel Ekroth, Uppsala, Chairman Dr Lena Sjögren, Stockholm, Vice-chairman Mrs Kristina Björksten Jersenius, Stockholm, Treasurer Dr Susanne Berndt, Stockholm, Secretary Prof. Christer Henriksén, Uppsala Prof. Anne-Marie Leander Touati, Lund Prof. Peter M. Fischer, Göteborg Dr David Westberg, Uppsala Dr Sabrina Norlander-Eliasson, Stockholm Dr Lewis Webb, Göteborg Dr Ulf R. Hansson, Rome Dr Jenny Wallensten, Athens EDITOR Dr Julia Habetzeder Department of Archaeology and Classical Studies Stockholm University SE-106 91 Stockholm [email protected] SECRETARY’S ADDRESS Department of Archaeology and Classical Studies Stockholm University SE-106 91 Stockholm [email protected] DISTRIBUTOR eddy.se ab Box 1310 SE-621 24 Visby For general information, see http://ecsi.se For subscriptions, prices and delivery, see http://ecsi.bokorder.se Published with the aid of a grant from The Swedish Research Council (2017-01912) The English text was revised by Rebecca Montague, Hindon, Salisbury, UK Opuscula is a peer reviewed journal. Contributions to Opuscula should be sent to the Secretary of the Editorial Committee before 1 November every year. Contributors are requested to include an abstract summarizing the main points and principal conclusions of their article. For style of references to be adopted, see http://ecsi.se. Books for review should be sent to the Secretary of the Editorial Committee. ISSN 2000-0898 ISBN 978-91-977799-2-0 © Svenska Institutet i Athen and Svenska Institutet i Rom Printed by TMG Sthlm, Sweden 2020 Cover illustrations from Aïopoulou et al. -

Perfume Vessels in South-East Italy

Perfume Vessels in South-East Italy A Comparative Analysis of Perfume Vessels in Greek and Indigenous Italian Burials from the 6th to 4th Centuries B.C. Amanda McManis Department of Archaeology Faculty of Arts University of Sydney October 2013 2 Abstract To date there has been a broad range of research investigating both perfume use in the Mediterranean and the cultural development of south-east Italy. The use of perfume was clearly an important practice in the broader Mediterranean, however very little is known about its introduction to the indigenous Italians and its subsequent use. There has also been considerable theorising about the nature of the cross-cultural relationship between the Greeks and the indigenous Italians, but there is a need for archaeological studies to substantiate or refute these theories. This thesis therefore aims to make a relevant contribution through a synthesis of these areas of study by producing a preliminary investigation of the use of perfume vessels in south-east Italy. The assimilation of perfume use into indigenous Italian culture was a result of their contact with the Greek settlers in south-east Italy, however the ways in which perfume vessels were incorporated into indigenous Italian use have not been systematically studied. This thesis will examine the use of perfume vessels in indigenous Italian burials in the regions of Peucetia and Messapia and compare this use with that of the burials at the nearby Greek settlement of Metaponto. The material studied will consist of burials from the sixth to fourth centuries B.C., to enable an analysis of perfume use and social change over time. -

SPECIAL TOURS MYTHOLOGY Gallery of Greek and Roman Casts

SPECIAL TOURS MYTHOLOGY Gallery of Greek and Roman Casts Battle of the Greeks and Amazons Temple of Apollo at Phigaleia (Bassai) Greek, late 5th c. B.C. The Mausoleion at Halikarnassos Greek, ca. 360-340 B.C. Myth: The Amazons lived in the northern limits of the known world. They were warrior women who fought from horseback usually with bow and arrows, but also with axe and spear. Their shields were crescent shaped. They destroyed the right breast of young Amazons, to facilitate use of the bow. The Attic hero Theseus had joined Herakles on his expedition against them and received the Amazon Antiope (or Hippolyta) as his share of the spoils of war. In revenge, the Amazons invaded Attica. In the subsequent battle Antiope was killed. This battle was represented in a number of works, notably the metopes of the Parthenon and the shield of the Athena Parthenos, the great cult statue by Pheidias that stood in the Parthenon. Symbolically, the battle represents the triumph of civilization over barbarism. Battle of the Gods and Giants Altar of Zeus and Athena, Pergamon (Zeus battling Giants) Greek, ca. 180 B.C. Myth: The giants, born of Earth, threatened Zeus and the other gods, and a fierce struggle ensued, the so-called Gigantomachy, or battle of the gods and giants. The giants were defeated and imprisoned below the earth. This section of the frieze from the altar shows Zeus battling three giants. The myth may reflect an event of prehistory, the arrival ca. 2000 B.C. of Greek- speaking invaders, who brought with them their own gods, whose chief god was Zeus. -

Ancient Mediterranean Gallery Labels

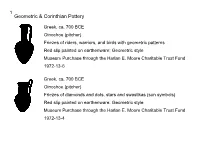

1 Geometric & Corinthian Pottery Greek, ca. 700 BCE Oinochoe (pitcher) Friezes of riders, warriors, and birds with geometric patterns Red slip painted on earthenware; Geometric style Museum Purchase through the Harlan E. Moore Charitable Trust Fund 1972-13-6 Greek, ca. 700 BCE Oinochoe (pitcher) Friezes of diamonds and dots, stars and swastikas (sun symbols) Red slip painted on earthenware; Geometric style Museum Purchase through the Harlan E. Moore Charitable Trust Fund 1972-13-4 2 Geometric & Corinthian Pottery (cont.) Greek, Corinthian, ca. 580 BCE Kotyle (stemless drinking cup) Banded decoration with aquatic birds, panthers, and goats Black and red slip painted on earthenware; “Wild Style” Museum Purchase through the Harlan E. Moore Charitable Trust Fund 1970-9-1 Greek, Corinthian, ca. 600 BCE Olpe (pitcher) Banded decoration of swans, goats, panthers, boars, and sirens Black, red, and white slip painted on earthenware; Moore Painter Museum Purchase through the Harlan E. Moore Charitable Trust Fund 1970-9-2 3 Geometric & Corinthian Pottery (cont.) Greek, Corinthian, ca. 600–590 BCE Oinochoe (pitcher) Banded decoration of owl, sphinx, aquatic bird, panthers, and lions Black, red, and white slip painted on earthenware Museum Purchase through the Harlan E. Moore Charitable Trust Fund 1970-9-4 4 Greek Black-figure Pottery Greek, Attic, ca. 550 BCE Amphora (storage jar) Equestrian scenes Black-figure technique; Pointed Nose Painter (Tyrrhenian group) Museum Purchase through the Harlan E. Moore Charitable Trust Fund 1970-9-3 Greek, Attic, ca. 530–520 BCE Kylix (stemmed drinking cup) Exterior: Apotropaic eyes and Athena battling Giants Interior medallion: Triton Black-figure technique on earthenware; after Exekias Museum Purchase through the Harlan E. -

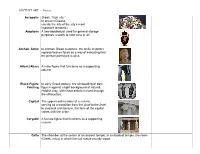

Art Concepts

ANCIENT ART - Greece Acropolis Greek, “high city.” In ancient Greece, usually the site of the city’s most important temple(s). Amphora A two-handled jar used for general storage purposes, usually to hold wine or oil. Archaic Smile In Archaic Greek sculpture, the smile sculptors represented on faces as a way of indicating that the person portrayed is alive. Atlant (Atlas) A male figure that functions as a supporting column. Black-Figure In early Greek pottery, the silhouetting of dark Painting figures against a light background of natural, reddish clay, with linear details incised through the silhouettes. Capital The uppermost member of a column, serving as a transition from the shaft to the lintel. In classical architecture, the form of the capital varies with the order. Caryatid A female figure that functions as a supporting column. Cella The chamber at the center of an ancient temple; in a classical temple, the room (Greek, naos) in which the cult statue usually stood. ANCIENT ART - Greece Centaur In ancient Greek mythology, a fantastical creature, with the front or top half of a human and the back or bottom half of a horse. Contrapposto The disposition of the human figure in which one part is turned in opposition to another part (usually hips and legs one way, shoulders and chest another), creating a counterpositioning of the body about its central axis. Sometimes called “weight shift” because the weight of the body tends to be thrown to one foot, creating tension on one side and relaxation on the other. Corinthian Corinthian columns are the latest of the three Greek styles and show the influence of Egyptian columns in their capitals, which are shaped like inverted bells.