Two Red Figure Vases and the Stories They Tell

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

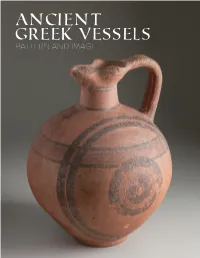

Ancient Greek Vessels Pattern and Image

ANCIENT GREEK VESSELS PATTERN AND IMAGE 1 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS It is my pleasure to acknowledge the many individuals who helped make this exhibition possible. As the first collaboration between The Trout Gallery at Dickinson College and Bryn Mawr and Wilson Colleges, we hope that this exhibition sets a precedent of excellence and substance for future collaborations of this sort. At Wilson College, Robert K. Dickson, Associate Professor of Fine Art and Leigh Rupinski, College Archivist, enthusiasti- cally supported loaning the ancient Cypriot vessels seen here from the Barron Blewett Hunnicutt Classics ANCIENT Gallery/Collection. Emily Stanton, an Art History Major, Wilson ’15, prepared all of the vessels for our initial selection and compiled all existing documentation on them. At Bryn Mawr, Brian Wallace, Curator and Academic Liaison for Art and Artifacts, went out of his way to accommodate our request to borrow several ancient Greek GREEK VESSELS vessels at the same time that they were organizing their own exhibition of works from the same collection. Marianne Weldon, Collections Manager for Special Collections, deserves special thanks for not only preparing PATTERN AND IMAGE the objects for us to study and select, but also for providing images, procuring new images, seeing to the docu- mentation and transport of the works from Bryn Mawr to Carlisle, and for assisting with the installation. She has been meticulous in overseeing all issues related to the loan and exhibition, for which we are grateful. At The Trout Gallery, Phil Earenfight, Director and Associate Professor of Art History, has supported every idea and With works from the initiative that we have proposed with enthusiasm and financial assistance, without which this exhibition would not have materialized. -

A Black-Figured Kylix from the Athenian Agora

A BLACK-FIGUREDKYLIX FROM THE ATHENIAN AGORA (PLATES 31 AND 32) I N THE spring of 1950 an ancientwell was discoveredin the area behindthe Stoa of Attalos, just east of the sixth shop from the south.' It was excavated to the bottom which was reached at a depth of 7.70 meters below the present surface of bedrock. The well was beautifully cut, round and true, in the soft green clayey bed- rock, and on two sides, the northwest and southwest, there was a series of fifteen footholds designed to help the workman who was digging the well in going down and coming up. No trace was found of the house that this well was designed to serve nor was the contemporary ground level preserved at any point near by. A pillaged foundation trench of classical Greek times passed over the mouth of the well except for the very northernmost segment, the broad deep footing trench for the back wall of the Stoa of Attalos passed about two meters to the west of the well, and a drain of the Roman period barely a meter to the east. The few remaining " islands " where bedrock stood to a higher level preserved no trace of ancient deposit. The fill in the upper meter or so of the well was loose bedrock without sherds. The next two meters produced scattered fragments of pottery of the first half of the sixth century B.C., one box full in all, among which we may note two black-figured frag- ments with animal friezes, rudely drawn, a fragmentary lid of a powder-box pyxis belonging to the Swan Group,2a fragment of a small late Corinthian skyphos with a zone of elongated animals, and several fragmentary unfigured kylixes, one of "komast " shape and two shaped like "Ionian" kylixes and having their off-set lips decorated inside with bands of thinned glaze.4 The next four and a half meters contained no sherds whatsoever, and the fill consisted sometimes of loose bedrock, occasionally of black mud. -

The Underworld Krater from Altamura

The Underworld Krater from Altamura The Underworld krater was found in 1847 in Altamura in 1 7 Persephone and Hades Herakles and Kerberos ITALY southeastern Italy. The ancient name of the town is unknown, Hades, ruler of the Underworld, was the brother of Zeus (king of the gods) and Poseidon (god of The most terrifying of Herakles’s twelve labors was to kidnap the guard dog of the Underworld. APULIA Naples but by the fourth century bc it was one of the largest fortified Altamura the sea). He abducted Persephone, daughter of the goddess Demeter, to be his wife and queen. For anyone who attempted to leave the realm of the dead without permission, Kerberos (Latin, Taranto (Taras) m settlements in the region. There is little information about Although Hades eventually agreed to release Persephone, he had tricked her into eating the seeds Cerberus) was a threatening opponent. The poet Hesiod (active about 700 BC) described the e d i t e r of a pomegranate, and so she was required to descend to the Underworld for part of each year. “bronze-voiced” dog as having fifty heads; later texts and depictions give it two or three. r a what else was deposited with the krater, but its scale suggests n e a n Here Persephone sits beside Hades in their palace. s e a that it came from the tomb of a prominent individual whose community had the resources to create and transport such a 2 9 substantial vessel. 2 The Children of Herakles and Megara 8 Woman Riding a Hippocamp Map of southern Italy marking key locations mentioned in this gallery The inhabitants of southeastern Italy—collectively known as The Herakleidai (children of Herakles) and their mother, Megara, are identified by the Greek The young woman riding a creature that is part horse, part fish is a puzzling presence in the Apulians—buried their dead with assemblages of pottery and other goods, and large vessels inscriptions above their heads. -

Kourimos Parthenos

KOURIMOS PARTHENOS The fragments of an oinochoe ' illustrated here preserve for us the earliest known representation in any medium of the dress and the masks worn by actors in Attic tragedy.2 The style of the vase suggests a date in the neighborhood of 470: 3 a time, that is, when both Aischylos and Sophokles 4 were active in the theatre. Thus, even though our fragments may not shed much new light on the " dark history of the IInv. No. P 11810. Three fragments, mended from five. Height; a, 0.073 m.; b, 0.046 m.; c, 0.065 m. From a round-bodied oinochoe, Beazley Shape III; fairly thin fabric, excellent glaze; relief contour except for the mask; sketch lines on the boy's body. The use of added color is described below, p. 269. For the lower border, a running spiral, with small loops between the spirals. Inside, dull black to brown glaze wash. The fragments were found just outside the Agora Excava- tions, near the bottom of a modern sewer trench along the south side of the Theseion Square, some 200 m. to the south of the temple, at a depth of about 3 m. below the street level. 2 For the fifth century, certainly, relevant comparative material has been limited to three pieces: the relief from the Peiraeus, now in the National Museum, Athens (N. M. 1500; Svoronos, Athener Nationalmuseum, pl. 82), which shows three actors, two of them carrying masks, approaching a reclining Dionysos; the Pronomos vase in Naples (Furtwangler-Reichhold, pls. 143-145), with its elaborate preparations for a satyr-play; and the pelike in Boston, by the Phiale painter (Att. -

Catullus, Archilochus and the 'Motto'. Two Poems of Catullus Have Long Been Compared with Fragments of Ar- Chilochus

I TWO CATULLIAN QUESTIONS L Catullus, Archilochus and the 'motto'. Two poems of Catullus have long been compared with fragments of Ar- chilochus. First, Catullus 40 and Archilochus 172 West (fully discussed by Hendrickson "CP" 20, 1925, 155); qwenan te mala mew, miselle Ravide, agit praccípítem in rrcos iambos ? quid dcus rtbi nonbene ad.vocatus ve cordcm parat excímre rimn? an uî penenias ín oravulgi? quidvis? qunlubet esse natus oPns? eris, quando quidcm mcos cttnores cwn longavoluisti amare poena. n&rep Auróppa, noîov Érppóoco tó6e tíg oùg rccr,p{epe epwctg fig cò rpìv ;1pfipqoOa; vOv òè 6l rol.ùq úocoîot gcwérrt fflog. This is known to be the beginning of a poem, since Hephaestion, who quotes l-2, only adduces the beginnings of poems; 2I0 ríg &pa òaíprov (quis d.eus) raì téoo 1oX,oúpevoE may well come from the same context. Moreover, as Hendrickson remarks, Lucian's (Pseudol. 1) paraphrase of the context of 223, which he says was addressed to one of toò6 repureteîg é,oopévoog (cf. praecípítem) rfi 1ol.fr t6v iópporv crúto0 who had re- viled the poet, seems to indicate that it went with 172; ín that case Lucian's 6 rcróòatpov &v0prone=míselle, and aiticq (qtoOvtc rai ùro0é- oeqtoî6 iúpporq will help to explain Catullus' application of iantbi to hen- decasyllables (though it does not need much explanation; cf. 54.6 and fr. 3). If Catullus had Archilochus in mind, he diverged from him in the last two lines, which envisage a situaúon quite different from that between Archilo- chus and Lycambes; the poem of Archilochus seems to have continued at considerable length and included the fable of the fox and the eagle (172- 181). -

A Masterpiece of Ancient Greece

Press Release A Masterpiece of Ancient Multimedia Greece: a World of Men, Feb. 01 - Sept. 01 2013 Gods, and Heroes DNP, Gotanda Building, Tokyo Louvre - DNP Museum Lab Tenth presentation in Tokyo The tenth Louvre - DNP Museum Lab presentation, which closes the second phase of this partnership between the Louvre and Dai Nippon Printing Co., Ltd (DNP), invites visitors to discover the art of ancient Greece, a civilization which had a significant impact on Western art and culture. They will be able to admire four works from the Louvre's Greek art collection, and in particular a ceramic masterpiece known as the Krater of Antaeus. This experimental exhibition features a series of original multimedia displays designed to enhance the observation and understanding of Greek artworks. Three of the displays designed for this presentation are scheduled for relocation in 2014 to the Louvre in Paris. They will be installed in three rooms of the Department of Greek, Etruscan and Roman Red-figure calyx krater Signed by the painter Euphronios, attributed to the Antiquities, one of which is currently home to the Venus de Milo. potter Euxitheos. Athens, c. 515–510 BC. Clay The first two phases of this project, conducted over a seven-year Paris, Musée du Louvre. G 103 period, have allowed the Louvre and DNP to explore new © Photo DNP / Philippe Fuzeau approaches to art using digital and imaging technologies; the results have convinced them of the interest of this joint venture, which they now intend to pursue along different lines. Location : Louvre – DNP Museum Lab Ground Floor, DNP - Gotanda 3-5-20 Nishi-Gotanda, Shinagawa-ku, Tokyo The "Krater of Antaeus", one of the Louvre's must-see masterpieces, Opening period : provides a perfect illustration of the beauty and quality of Greek Friday February 1 to Sunday September 1, ceramics. -

Evaluation of Attic Vase Painting in the Context of Art of Painting

_____________________________________________________ART-SANAT 7/2017_____________________________________________________ EVALUATION OF ATTIC VASE PAINTING IN THE CONTEXT OF ART OF PAINTING ÜFTADE MUŞKARA Assist. Prof., Kocaeli University, Faculty of Fine Arts, Department of Conservation and Restoration of Cultural Properties [email protected] SERPİL ŞAHİN Res. Assist., Kocaeli University, Faculty of Fine Arts, Painting Department ABSTRACT The attribution of vases to particular individual hands based on the signatures of painters or potters on the vases, the connoisseurship, obtained too much importance especially in the case of Athenian black figure and red figure pottery. It is because; through close examination of details of style it becomes possible to establish the interaction between “artists” and a sequential chronology for vases of black figure and red figure techniques. But some scholars have raised doubts on the limits of such studies. Re- examination of our perception of artist in connection with the attribution studies for Attic figured pottery and the idea supporting connoisseurship are necessary. Determination of figured pottery from a canvas painter’s point of expertise could illuminate the limitations and real context of attribution studies. Keywords: Attic vase painters, attribution studies, the connoisseurship, Morellian method. ATTİK VAZO RESMİNİN RESİM SANATI BAĞLAMINDA DEĞERLENDİRİLMESİ ÖZ Arkeolojide, Attik siyah figür ve kırmızı figür vazolarının vazolar üzerindeki çömlekçi ya da ressam imzalarından yola çıkarak özellikle belirli bireylere, ressamlara, atfedilmesi çok önem taşıyan çalışmalardır. Bunun nedeni, vazo resimlerinin detaylı incelenmesi ve stil kritiği ile ressamlar arasında ilişkiyi kurmak ve siyah figür ve kırmızı figür vazolar için bir kronoloji oluşturmanın mümkün olmasıdır.Ancak bu alanda çalışan bazı bilim insanlarının, çalışmaların sınırları ile ilgili şüpheleri vardır. -

A Mycenaean Ritual Vase from the Temple at Ayia Irini, Keos

A MYCENAEAN RITUAL VASE FROM THE TEMPLE AT AYIA IRINI, KEOS (PLATE 18) D URING the 1963 excavations of the University of Cincinnatiat Ayia Irini, a number of fragments belonging to a curious and important Mycenaean vase were discovered in the Temple, mostly in Rooms IV and XI where they were found widely scattered in the post-Late Minoan IB earthquake strata.' Since it is impos- sible to date the vase stratigraphically, it is hoped that analysis of its shape and decoration may contribute something to our knowledge of the later history of the Temple in its Mycenaean period. Unfortunately, the vase is so fragmentary and its decoration so unstandardized that this is no simple task. It is the goal of this paper to look critically at the fragments and see what they suggest for the re- construction of the vase, its probable date and affinities, and its function in the Temple. Following two main lines of approach, we will first attempt a reconstruction of the shape and then analyze the pictorial decoration. Both are important in deter- mining date, possible provenience, and function. The fragments fall into three main groups: 1) those coming from the shoulder and upper part of an ovoid closed pot with narrow neck, now made up into two large fragments which do not join but which constitute about one-third the circumference (P1. 18 :a, b, c); 2) at least two fragments from the lower part of a tapering piriform shape (P1. 18 :d, d and e) ; 3) fragments of one or more hollow ring handles (P1. -

Greek Pottery Gallery Activity

SMART KIDS Greek Pottery The ancient Greeks were Greek pottery comes in many excellent pot-makers. Clay different shapes and sizes. was easy to find, and when This is because the vessels it was fired in a kiln, or hot were used for different oven, it became very strong. purposes; some were used for They decorated pottery with transportation and storage, scenes from stories as well some were for mixing, eating, as everyday life. Historians or drinking. Below are some have been able to learn a of the most common shapes. great deal about what life See if you can find examples was like in ancient Greece by of each of them in the gallery. studying the scenes painted on these vessels. Greek, Attic, in the manner of the Berlin Painter. Panathenaic amphora, ca. 500–490 B.C. Ceramic. Bequest of Mrs. Allan Marquand (y1950-10). Photo: Bruce M. White Amphora Hydria The name of this three-handled The amphora was a large, two- vase comes from the Greek word handled, oval-shaped vase with for water. Hydriai were used for a narrow neck. It was used for drawing water and also as urns storage and transport. to hold the ashes of the dead. Krater Oinochoe The word krater means “mixing The Oinochoe was a small pitcher bowl.” This large, two-handled used for pouring wine from a krater vase with a broad body and wide into a drinking cup. The word mouth was used for mixing wine oinochoe means “wine-pourer.” with water. Kylix Lekythos This narrow-necked vase with The kylix was a drinking cup with one handle usually held olive a broad, relatively shallow body. -

Attic Black Figure from Samothrace

ATTIC BLACK FIGURE FROM SAMOTHRACE (PLATES 51-56) 1 RAGMENTS of two large black-figure column-kraters,potted and painted about j1t the middle of the sixth century, have been recovered during recent excavations at Samothrace.' Most of these fragments come from an earth fill used for the terrace east of the Stoa.2 Non-joining fragments found in the area of the Arsinoeion in 1939 and in 1949 belong to one of these vessels.3 A few fragments of each krater show traces of burning, for either the clay is gray throughout or the glaze has cracked because of intense heat. The surface of many fragments is scratched and pitted in places, both inside and outside; the glaze and the accessory colors, especially the white, have sometimes flaked. and the foot of a man to right, then a woman A. Column krater with decoration continuing to right facing a man. Next is a man or youtlh around the vase. in a mantle facing a sphinx similar to one on a 1. 65.1057A, 65.1061, 72.5, 72.6, 72.7. nuptial lebes in Houston by the Painter of P1. 51 Louvre F 6 (P1. 53, a).4 Of our sphinx, its forelegs, its haunches articulated by three hori- P.H. 0.285, Diam. of foot 0.203, Th. at ground zontal lines with accessory red between them, line 0.090 m. and part of its tail are preserved. Between the Twenty-six joining pieces from the lower forelegs and haunches are splashes of black glaze portion of the figure zone and the foot with representing an imitation inscription. -

Classical Images – Greek Pegasus

Classical images – Greek Pegasus Red-figure kylix crater Attic Red-figure kylix Triptolemus Painter, c. 460 BC attr Skythes, c. 510 BC Edinburgh, National Museums of Scotland Boston, MFA (source: theoi.com) Faliscan black pottery kylix Athena with Pegasus on shield Black-figure water jar (Perseus on neck, Pegasus with Etrurian, attr. the Sokran Group, c. 350 BC Athenian black-figure amphora necklace of bullae (studs) and wings on feet, Centaur) London, The British Museum (1842.0407) attr. Kleophrades pntr., 5th C BC From Vulci, attr. Micali painter, c. 510-500 BC 1 New York, Metropolitan Museum of ART (07.286.79) London, The British Museum (1836.0224.159) Classical images – Greek Pegasus Pegasus Pegasus Attic, red-figure plate, c. 420 BC Source: Wikimedia (Rome, Palazzo Massimo exh) 2 Classical images – Greek Pegasus Pegasus London, The British Museum Virginia, Museum of Fine Arts exh (The Horse in Art) Pegasus Red-figure oinochoe Apulian, c. 320-10 BC 3 Boston, MFA Classical images – Greek Pegasus Silver coin (Pegasus and Athena) Silver coin (Pegasus and Lion/Bull combat) Corinth, c. 415-387 BC Lycia, c. 500-460 BC London, The British Museum (Ac RPK.p6B.30 Cor) London, The British Museum (Ac 1979.0101.697) Silver coin (Pegasus protome and Warrior (Nergal?)) Silver coin (Arethusa and Pegasus Levantine, 5th-4th C BC Graeco-Iberian, after 241 BC London, The British Museum (Ac 1983, 0533.1) London, The British Museum (Ac. 1987.0649.434) 4 Classical images – Greek (winged horses) Pegasus Helios (Sol-Apollo) in his chariot Eos in her chariot Attic kalyx-krater, c. -

Sleeping Furies: Allegory, Narration and the Impact of Texts in Apulian Vase-Painting*

Sleeping Furies: Allegory, Narration and the Impact of Texts in Apulian Vase-Painting* Luca Giuliani Picture-vases in a funerary context In this paper I shall discuss a few basic peculiarities of Apulian vase paint ing. I will proceed in two steps. First I shall concentrate on the difference between what I call narrative versus allegorical meaning; as meaning is al ways closely connected with function, I will start from the few things we know about the way Apulian vases were actually used. In the second part of the paper I shall concentrate on the iconography of (just) one mythological episode: we shall look at Orestes in Delphi, surrounded by the sleeping Fu ries, and we shall have to ask what can actually have been the reason for the painters to show Furies sound asleep. But let us begin at the beginning. The production of red-figure vases on the Gulf of Tarentum starts around the middle of the fifth century: the tech nique is Attic, Attic is the shape of the vases, Attic their iconography; the first potters and painters must have been of Attic origin, having had their training in the Athenian Kerameikos. For about one generation the connec tion between Apulian and Attic vase-production remains rather close: but around 400 BC the immigration of Attic vase painters as well as the import of Attic vases comes to a sudden end: from this time at the latest vase-production in Apulia develops to become a phenomenon of its own. * Many thanks to David Wasserstein for suggesting the publication o f my paper in this journal.