Reclamation of Derelict Industrial Land in Portugal: Greening Is Not Enough

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hygiea Internationalis

Regional Dynamics and Social Diversity – Portugal in the 21st Century Teresa Ferreira Rodrigues Introduction hrough its history Portugal always presented regional differences concerning population distribution, as well as fertility and mortality trends. Local T specificities related to life and death levels reflect diverse socioeconomic conditions and also different health coverage. We will try to diagnose the main concerns and future challenges related to those regional differences, using quantitative and qualitative data on demographic trends, well-being average levels and health services offer. We want to demonstrate that this kind of academic researches can be useful to policy makers, helping them: (1) to implement regional directed policies; (2) to reduce internal diversity; and (3) to improve quality of life in the most excluded areas. Our first issue consists in measuring the link between Portuguese modernization and asymmetries on social well-being levels1. Today Portugal faces some modera- tion on population growth rates, a total dependency on migration rates, both exter- nal and internal, as well as aged structures. But national average numbers are totally different from those at a regional level, mainly if using non demographic indicators, such as average living patterns or purchase power2. The paper begins with a short diagnosis on the huge demographic and socioeco- nomic changes of the last decades. In the second part we analyze the extent of the link between those changes and regional convergence on well-being levels. Finally, we try to determine the extent of regional contrasts, their main causes and the rela- tionship between social change and local average wealth standards, as well as the main problems and challenges that will be under discussion in the years to come, in what concerns to health policies. -

Rota Histórica Das Linhas De Torres G UIA Ficha Técnica

Rota Histórica das Linhas de Torres G UIA ficha técnica COORDENAÇÃO DESIGN Carlos Silveira www.tvmdesigners.pt Carlos Guardado da Silva EDIÇÃO Ana Catarina Sousa PILT – Plataforma Intermunicipal Graça Soares Nunes para as Linhas de Torres TEXTOS Ana Catarina Sousa [ACS] IMPRESSÃO Gráfica Maiadouro Ana Correia [AC] TIRAGEM 6000 exemplares Carlos Guardado da Silva [CGS] DEPÓSITO LEGAL 338 329/12 Carlos Silveira [CS] 1ª EDIÇÃO – NOVEMBRO 2011 Florbela Estêvão [FE] Paula Ferreira [PF] CATALOGAÇÃO Sandra Oliveira [SO] Rota Histórica das Linhas de Torres : Guia / coord. REVISÃO Carlos Silveira, Carlos Guardado da Silva, Ana Catarina Equipa da UT5 – Publicações Sousa, Graça Soares Nunes; [textos de] Ana Catarina Francisco de Sousa Lobo Sousa, Ana Correia, Carlos Guardado da Silva, Carlos Silveira, Florbela Estêvão, Paula Ferreira, EQUIPA DA UNIDADE TÉCNICA 5 – PUBLICAÇÕES Sandra Oliveira. – Vila Franca de Xira : PILT, 2011. Graça Soares Nunes – 120 p. : il. ; 20 cm Ana Catarina Sousa ISBN 978-989-8398-14-7 Ana Correia Carlos Guardado da Silva Carlos Silveira CDU Florbela Estêvão 355.48 Linhas de Torres Vedras (036) Isabel Silva 94(469.411)“1809/1811” (036) Joaquim Jorge 94(4)“1807/1814” (036) Natália Calvo Paula Ferreira Rui Brás Sandra Oliveira SIGLAS Susana Gonçalves CMAV Câmara Municipal de Arruda dos Vinhos CML Câmara Municipal de Loures CRÉDITOS FOTOGRÁFICOS CMM Câmara Municipal de Mafra António Pedro Vicente CMSMA Câmara Municipal de Sobral de Monte Agraço Biblioteca Nacional de Portugal CMTV Câmara Municipal de Torres Vedras Câmara Municipal -

Relatorio E Contas 2016

CAIXA DE CRÉDITO AGRÍCOLA MÚTUO DE LOURES, SINTRA E LITORAL, CRL | Relatório e Contas 2016 2 Índice 00 CAIXA DE CRÉDITO AGRÍCOLA MÚTUO DE LOURES, SINTRA E LITORAL, CRL | Relatório e Contas 2016 3 CAIXA DE CRÉDITO AGRÍCOLA MÚTUO DE LOURES, SINTRA E LITORAL, CRL | Relatório e Contas 2016 4 0. ÍNDICE 3 1. ENQUADRAMENTO ECONÓMICO 7 1.1. Economia Mundial 9 1.2. Economia Portuguesa 13 1.3. Mercado Bancário 17 1.3.1. Evolução do Mercado Nacional de Depósitos 17 1.3.2. Evolução do Mercado Nacional de Crédito 18 1.4. Mercados Financeiros 21 1.5. Principais Riscos e Incertezas para 2017 25 2. GRUPO CRÉDITO AGRÍCOLA 27 2.1. Análise Financeira do Negócio Bancário do Grupo CA 29 2.2. Outros Factos Relevantes 37 3. A REALIDADE DA CAIXA DE CRÉDITO AGRÍCOLA MÚTUO DE LOURES, SINTRA E LITORAL, C.R.L. 41 3.1. Aspetos Mais Relevantes 45 3.2. Apresentação da CCAM 47 3.2.1. Estrutura de capital 47 3.2.2. Marcos históricos 47 3.2.3. Rede de distribuição 49 3.2.4. Recursos humanos 51 4. ESTRATÉGIA E ÁREA DE NEGÓCIO 53 4.1 Objetivos Estratégicos 55 4.2 Resultados 57 4.2.1. Resultados 57 4.2.2. Margem financeira 59 4.2.3. Produto bancário 60 4.2.4. Custos operacionais 61 4.2.5. Resultado operacional 62 4.2.6. Resultado antes de imposto 62 4.2.7. Resultado líquido 62 4.3. Balanço 64 4.3.1. Crédito concedido 69 4.3.2. Crédito vencido 70 4.3.3. -

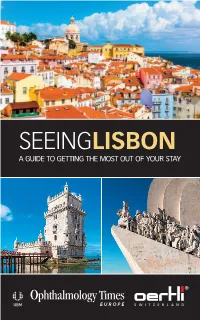

Seeinglisbon a Guide to Getting the Most out of Your Stay

SEEINGLISBON A GUIDE TO GETTING THE MOST OUT OF YOUR STAY magentablackcyanyellow ES959734_OTECG0817_cv1.pgs 08.22.2017 19:44 ADV It‘s Better, It‘s Different – Welcome to the city of discoverers Vasco da Gama began his ingenious discovery tours in the city on the western edge of Europe and greatly enhanced people’s conception of the world. He strongly questioned some approaches to knowledge and paved the way for trade with India. Following his achievements, Lisbon enjoyed a time of great prosperity that came to a sudden end following the disastrous earthquake in 1755. What we experience as an impressive city image today, especially the Baixa, was created in the 18th century. Only the Torre de Belém still reminds us of the time of great sailors and their untiring spirit of discovery. Of course, the time of individual explorations is long past, but the urge for new knowledge has remained unchanged. Today, it is a great number of people who work on the front lines with curiosity, diligence and persistence to bring about progress. They have come to Lisbon as well, to make new discoveries by sharing scientific and practical approaches. Not only in lectures, workshops and discussions but also in dialogues with industry, at the Oertli booth for example. Discover the total range of cataract and posterior segment surgical platforms, the latest functions of the OS4 device, an amazingly simple MIGS method and the new FEELceps line, or simply discover the friendliness and competence of our employees at booth no P263. We warmly welcome you! magentablackcyanyellow -

English Version

Visit LOURES So much to → →> SANTO ANTÓNIO DOS CAVALEIROS | Chapel of the Holy Spirit. Quinta do Conventinho SANTO ANTÃO DO TOJAL | Aqueduct [PIM] LOURES | Church of Santa Maria de Loures [NM] SANTO ANTÃO DO TOJAL | The Monumental Square [PIM] HERE IS heritage! LOUSA | Altar of the Church of São Pedro [BPI] We enrich and recovered memories, traditions, values and spaces that the culture and our ancestors bequeathed us. SANTA IRIA DE AZÓIA | One of the oldest olive trees in Portugal Home ← → →> SACAVÉM | Sacavém Ceramic Museum SANTO ANTÓNIO DOS CAVALEIROS | Municipal Museum of Loures HERE IS culture! BUCELAS | Museum of Vine and Wine The museum and galleries of Loures make us complicit in centuries of history that, collectively, continue to give meaning and to strengthen the identity of this territory. LOURES | Municipal Gallery Vieira da Silva Promote the heritage is to reinforce, with affection, the most identity of all: people and their ways of life. SANTA IRIA DE AZÓIA | Castle of Pirescouxe Home ← → →> URBAN ART | Terraços da Ponte, Sacavém HERE IS diversity! FOLKLORE | Ethnographic group Synonyms of culture and social identity, multiculturalism, handicraft and folklore transmit the traditions and customs of saloia’s region and all those who chose to live in. HANDICRAFT | Work done in clay BUCELAS | Feast of the wine and the grape harvest MUSIC | Meeting of Philharmonic Bands and Small Orchestras of Loures InícioHome ← → →> TRADITIONAL CUISINE | Pataniscas of cod CHEESE FACTORY | Saloios cheeses ARINTO’S CASTE | Grapes for the production of the white wines [QWPDR] VINEYARDS | Demarcated Wine Region of Bucelas HERE ARE flavours! TRADITIONAL CUISINE | Sweet scones Taste the delicacies, as well as the typical and refined products from this region, WINE TOURISM | Bucelas’ Wine is to rediscover our WINE TOURISM | Carrafouchas’ Vineyard roots, where features the wines and cheeses. -

The Festivities of the Light of Carnide: a Persistent Authenticity

Papers 375 The festivities of the Light of Carnide: a persistent authenticity M. I. Roque Universidade Europeia – Laureate International Universities, Lisbon, Portugal CIDEHUS.UÉ – Centro Interdisciplinar de História, Culturas e Sociedades da Universidade de Évora, Évora, Portugal M. J. Forte Universidade Europeia – Laureate International Universities, Lisbon, Portugal ABSTRACT: The Círio of Our Lady of the Cabo, also known as Círiodos Saloios, has been a pilgrimage since the XV century far from the sanctuary at cap Espichel to the far away rural communities of the neighbouring diocese of Lisbon. The Círio of Our Lady of the Cabo is related to the feast of Our Lady of the Light of Carnide, a bordering neighbourhood of Lisbon. The festival, which is held annually in September, culminates in a procession attracting many foreigners to the local. As a popular religiosity phenomenon, it concerns its intangible heritage and asserts an important trace of its cultural identity. Nevertheless, blending the sacred and the profane, it incorporates extrinsic components related to a social, cultural and touristic dimension. Tourism, although offering opportunities to the local development, also presents a challenge to preserve the local authenticity without compromising the dynamics of the inherent hybridity between locals and outsiders. In order to understand the phenomenon and its ambivalences and adjustments, a qualitative study is proposed, comprising a literary revision about the Círio and the local devotion to Our Lady of the Light across times, non-structured interviews with the locals and a participant observation of the festivities since 2015. The research, even being descriptive, is designed as a correlational study, analyzing the impact of tourism in the religious sense of the event. -

FULLTEXT01.Pdf

http://www.diva-portal.org This is the published version of a paper published in European Journal of Public Health. Citation for the original published paper (version of record): Briones-Vozmediano, E., Stjärnfeldt, J., Larson, F., Nielsen, A., Eriksson, M. et al. (2020) Young men's discourses of health service utilization for Chlamydia infection testing in Stockholm European Journal of Public Health, 30(Issue Supplement_5): ckaa166.854 https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckaa166.854 Access to the published version may require subscription. N.B. When citing this work, cite the original published paper. Permanent link to this version: http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:umu:diva-179521 16th World Congress on Public Health 2020 2020–01 v847 reported genital cancers as complication to STD, 32.7% Young men’s discourses of health service utilization infertility. Some minorities (2.7%) thought that STD could for Chlamydia infection testing in Stockholm be complicated by blindness. Erica Briones-Vozmediano Conclusions: 1,2 2 2 2 Despite the high prevalence of STD among young adults, most E Briones-Vozmediano , J Stja¨ rnfeldt , F Larson , A Nielsen , M Eriksson3, M Salazar2 students knew very little about those infections. Implementing 1Department of Nursing and Physiotherapy, University of Lleida, Lleida, sexual educational programs and measuring their effectiveness Spain should be a priority. 2Department of Global Public Health, Karolinska Institut, Stockholm, Key messages: Sweden 3Department of Social Work, University of Umea˚ , Umea˚ , Sweden There is a huge lack of knowledge about sexually Contact: [email protected] Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/eurpub/article/30/Supplement_5/ckaa166.854/5915222 by Umea universitet user on 03 February 2021 Transmitted diseases among Tunisian college students. -

Sustainable Urban Mobility Policies As a Path to Healthy Cities—The Case Study of LMA, Portugal

sustainability Article Sustainable Urban Mobility Policies as a Path to Healthy Cities—The Case Study of LMA, Portugal Ana Louro *, Nuno Marques da Costa and Eduarda Marques da Costa Centre for Geographical Studies, Institute of Geography and Spatial Planning, Universidade de Lisboa, Rua Branca Edmée Marques, 1600-276 Lisboa, Portugal; [email protected] (N.M.d.C.); [email protected] (E.M.d.C.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +351-210-443-000 Received: 6 February 2019; Accepted: 17 May 2019; Published: 23 May 2019 Abstract: Sustainable development has become the basis of several worldwide policies over the last few decades, and its role will continue to shape policies for decades to come, especially those that are focused on urban mobility. At the same time, urban mobility is included in the framework of the Healthy Cities movement. In this context, using the Lisbon Metropolitan Area (LMA), Portugal, as the study area, this article intends to answer the following research question: are sustainable urban mobility policies contributing to healthy cities? Urban mobility planning and public health instruments were compared with the discourses and practices of those responsible for the implementation of urban mobility policies and Healthy Cities projects. The results reveal that a large number of responses proposed in the mobility planning instruments are, to some extent, related to the principles of healthy cities. Also, while municipal agents tend not to consider the inclusion of those principles, they instead incorporate the concepts of sustainable development. Nevertheless, we found that both approaches overlap the policy directions of healthy cities. -

Manual De Acolhimento

Gabinete do Cidadão ACES Loures – Odivelas Nota de Boas Vindas Este Manual tem como objectivo principal, dotar os novos colaboradores do Gabinete do Cidadão, dos conhecimentos essenciais sobre o ACES LOURES – ODIVELAS e, das informações e ferramentas necessárias facilitadoras da sua integração. Para o efeito, o Manual de Integração e Acolhimento está dividido em duas partes fundamentais: A apresentação do ACES e a apresentação do Gabinete do Cidadão. Esperamos que o Manual cumpra a sua função de acolhimento e integração do profissional e que este adquira as competências necessárias para o melhor desempenho da sua função e das actividades a ela inerentes. Votos de Bom Trabalho. Coordenadora Directora Executiva Gabinete do Cidadão ACES Loures-Odivelas _________________ ____________________ (Tânia Ferreira, Dra.) (Ileine Lopes, Dra.) Tânia Ferreira 01-10-2016 Gabinete do Cidadão ACES Loures – Odivelas (Baseado no Regulamento Interno) INTRODUÇÃO Tânia Ferreira 01-10-2016 Gabinete do Cidadão ACES Loures – Odivelas Os Centros de Saúde constituem o primeiro acesso dos cidadãos à prestação de cuidados de saúde, assumindo importantes funções de promoção da saúde e prevenção da doença, prestação de cuidados na doença e ligação a outros serviços para a continuidade dos cuidados. O DL n.º 28/2008, de 22 de Fevereiro, posteriormente alterado pelos DL n.º 81/2009, de 2 de Abril, DL n.º 102/2009 de 11 de Maio, DL n.º 248/2009 de 22 de Setembro, e DL n.º 253/2012 de 27 de Novembro, DL n.º 137/2013 de 7 de Outubro e DL n.º 239/2015 de 14 de outubro, criou os Agrupamentos de Centros de Saúde do Serviço Nacional de Saúde, designados por ACES, e estabeleceu o seu regime de organização e funcionamento. -

![ROTA HISTÓRICA DAS LINHAS DE TORRES [+351] 261 817 170 Tel.: E-Mail: Turismo@Cm-Mafra.Pt TURISMO LISBOA E VALE DO TEJO](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1566/rota-hist%C3%B3rica-das-linhas-de-torres-351-261-817-170-tel-e-mail-turismo-cm-mafra-pt-turismo-lisboa-e-vale-do-tejo-3381566.webp)

ROTA HISTÓRICA DAS LINHAS DE TORRES [+351] 261 817 170 Tel.: E-Mail: [email protected] TURISMO LISBOA E VALE DO TEJO

GU I A i Rota Histórica das Linhas de Torres Rota Histórica ARRUDA DOS VINHOS Descubra a Rota Histó rica das Linhas de Torres e viaje pela época gps: 38°58’60’’N; 09°04’40’’W das Invasões Napoleónicas, em seis percursos temáticos que tel.: [+351] 263 974 004 atravessam uma paisagem de contrastes onde a vista se perde e-mail: [email protected] www.cm-arruda.pt e se experimentam as tradições e sabores locais marcados pela história. Nas proximidades de Lisboa, entre o rio Tejo e LOURES o Oceano Atlântico, conheça o sistema de fortifi cações que gps: 38°49’36,50’’N; 09°09’38,03’’W tel.: [+351] 211 151 509/ 10 em 1810 marcou um ponto de viragem na Guerra Peninsular. e-mail: [email protected] www.cm-loures.pt MAFRA gps: 38°56’11,10’’N; 09°19’37,28’’W ROTA HISTÓRICA DAS LINHAS DE TORRES [+351] 261 817 170 tel.: www.rhlt.com.pt e-mail: [email protected] www.cm-mafra.pt TURISMO LISBOA E VALE DO TEJO SOBRAL DE MONTE AGRAÇO www.turismolisboavaledotejo.pt gps: 39°01’07,134”N; 09°09’05,520’’W TURISMO DO OESTE tel.: [+351] 261 942296 e-mail: [email protected] www.rt-oeste.pt www.cm-sobral.pt TURISMO DE PORTUGAL TORRES VEDRAS www.descubraportugal.pt gps: 39°05’29,13’’N; 09°15’31,87’’W Rota Histórica www.visitportugal.com tel.: [+351] 261 310 483 e-mail: [email protected] www.cm-tvedras.pt das Linhas de Torres VILA FRANCA DE XIRA gps: 38°57’13,055”N; 08°59’25,859’’W G U I A tel.: [+351] 263 285 605 e-mail: [email protected] www.cm-vfxira.pt Em 1810, a península a norte de Lisboa viu erguer-se percursos Torres VeDrAs nA primeirA LinhA um dos sistemas militares mais eficazes do Mundo, as Linhas de Torres Vedras. -

5 a Realidade Da Caixa De Crédito Agrícola Mútuo De Loures, Sintra E Litoral, C.R.L

Caixa de Crédito Agrícola Mútuo de Loures, Sintra e Litoral, C.R.L. RELATÓRIO E CONTAS 2017 CAIXA DE CRÉDITO AGRÍCOLA MÚTUO DE LOURES, SINTRA E LITORAL, CRL | Relatório e Contas 2017 2 Índice 00 CAIXA DE CRÉDITO AGRÍCOLA MÚTUO DE LOURES, SINTRA E LITORAL, CRL | Relatório e Contas 2017 3 CAIXA DE CRÉDITO AGRÍCOLA MÚTUO DE LOURES, SINTRA E LITORAL, CRL | Relatório e Contas 2017 4 0. ÍNDICE 3 1. ANÁLISE DA ENVOLVENTE EXTERNA 7 1.1. Enquadramento Macroeconómico 9 1.1.1. Economia Mundial 9 1.1.2. Economia Nacional 13 1.2. Economia e Tecido Empresarial 15 2. ANÁLISE DO MERCADO BANCÁRIO E FINANCEIRO 19 2.1. Mercado Bancário Nacional 21 2.1.1. Evolução do mercado nacional de depósitos (Dezembro 2012 – 21 Dezembro 2017) 2.1.2. Evolução do mercado nacional de crédito (Dezembro 2012 – 22 Dezembro 2017) 2.3. Mercado Financeiro 25 3. CRÉDITO AGRÍCOLA - EVOLUÇÃO RECENTE 31 3.1. Resultado e Balanço 33 3.1.1. Análise Financeira do Negócio Bancário do Grupo CA 33 3.1.2. Outros Factos Relevantes 38 4. PRINCIPAIS RISCOS E INCERTEZAS PARA 2018 45 5. A REALIDADE DA CAIXA DE CRÉDITO AGRÍCOLA MÚTUO DE LOURES, SINTRA E LITORAL, C.R.L. 49 5.1. Aspetos Relevantes 54 5.2. Apresentação da CCAM 56 5.2.1. Marcos Históricos 56 5.2.2. Estrutura de Capital 59 5.2.3. Rede de Distribuição 59 5.2.4. Recursos Humanos 63 6. ESTRATÉGIA E ÁREA DE NEGÓCIO 65 6.1. Objetivos Estratégicos 67 6.2. Demonstração de Resultados 69 6.2.1. -

Ramada, Odivelas

O sítio pré-histórico da Pedreira do Aires (Ramada,Odivelas): notícia da sua identificação1 MARCO ANTÓNIO ANDRADE2 MARISA S. CARDOSO2 RESUMOO presente trabalho tem como objectivo dar a conhecer a identificação de um sítio arqueo- lógico em precária situação de conservação. Pela avaliação do espólio recolhido e da implan- tação específica na paisagem, assim como do registo arqueológico envolvente, avança-se com uma proposta cronológica e funcional para o sítio. Ao que tudo indica, e tendo sempre em conta o carácter literalmente superficial dos dados recolhidos, estamos perante uma esta- ção possivelmente dedicada a uma actividade específica dentro da Pré-História das antigas sociedades camponesas da Península de Lisboa, embora outras interpretações possam e devam ser consideradas. ABSTRACTThis paper has the intent to inform about the identification of an archaeo- logical site in a precarious situation of preservation. With the evaluation of the recovered arte- facts and the specific implantation on the landscape, as well as the involving archaeological register, we advance with a chronological and functional proposal for the site. As it seems, and taking always in account the literally superficial character of the collected data, we have here a site possibly dedicated to a specific activity in the Prehistory of the ancient peasant societies of the Lisbon Peninsula, although other interpretations can and should be considered. 1. Localização e caracterização Identificado em inícios de 2002, numa visita casual à área, o sítio arqueológico da Pedreira do Aires situa-se à entrada do Bairro do Girassol, no início da Rua Aurélio Paz dos Reis, fregue- sia da Ramada, concelho de Odivelas.