Download (399Kb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Biographical Appendix

Biographical Appendix The following women are mentioned in the text and notes. Abney- Hastings, Flora. 1854–1887. Daughter of 1st Baron Donington and Edith Rawdon- Hastings, Countess of Loudon. Married Henry FitzAlan Howard, 15th Duke of Norfolk, 1877. Acheson, Theodosia. 1882–1977. Daughter of 4th Earl of Gosford and Louisa Montagu (daughter of 7th Duke of Manchester and Luise von Alten). Married Hon. Alexander Cadogan, son of 5th Earl of Cadogan, 1912. Her scrapbook of country house visits is in the British Library, Add. 75295. Alten, Luise von. 1832–1911. Daughter of Karl von Alten. Married William Montagu, 7th Duke of Manchester, 1852. Secondly, married Spencer Cavendish, 8th Duke of Devonshire, 1892. Grandmother of Alexandra, Mary, and Theodosia Acheson. Annesley, Katherine. c. 1700–1736. Daughter of 3rd Earl of Anglesey and Catherine Darnley (illegitimate daughter of James II and Catherine Sedley, Countess of Dorchester). Married William Phipps, 1718. Apsley, Isabella. Daughter of Sir Allen Apsley. Married Sir William Wentworth in the late seventeenth century. Arbuthnot, Caroline. b. c. 1802. Daughter of Rt. Hon. Charles Arbuthnot. Stepdaughter of Harriet Fane. She did not marry. Arbuthnot, Marcia. 1804–1878. Daughter of Rt. Hon. Charles Arbuthnot. Stepdaughter of Harriet Fane. Married William Cholmondeley, 3rd Marquess of Cholmondeley, 1825. Aston, Barbara. 1744–1786. Daughter and co- heir of 5th Lord Faston of Forfar. Married Hon. Henry Clifford, son of 3rd Baron Clifford of Chudleigh, 1762. Bannister, Henrietta. d. 1796. Daughter of John Bannister. She married Rev. Hon. Brownlow North, son of 1st Earl of Guilford, 1771. Bassett, Anne. Daughter of Sir John Bassett and Honor Grenville. -

Hereditary Genius Francis Galton

Hereditary Genius Francis Galton Sir William Sydney, John Dudley, Earl of Warwick Soldier and knight and Duke of Northumberland; Earl of renown Marshal. “The minion of his time.” _________|_________ ___________|___ | | | | Lucy, marr. Sir Henry Sydney = Mary Sir Robt. Dudley, William Herbert Sir James three times Lord | the great Earl of 1st E. Pembroke Harrington Deputy of Ireland.| Leicester. Statesman and __________________________|____________ soldier. | | | | Sir Philip Sydney, Sir Robert, Mary = 2d Earl of Pembroke. Scholar, soldier, 1st Earl Leicester, Epitaph | courtier. Soldier & courtier. by Ben | | Johnson | | | Sir Robert, 2d Earl. 3d Earl Pembroke, “Learning, observation, Patron of letters. and veracity.” ____________|_____________________ | | | Philip Sydney, Algernon Sydney, Dorothy, 3d Earl, Patriot. Waller's one of Cromwell's Beheaded, 1683. “Saccharissa.” Council. First published in 1869. Second Edition, with an additional preface, 1892. Fifith corrected proof of the first electronic edition, 2019. Based on the text of the second edition. The page numbering and layout of the second edition have been preserved, as far as possible, to simplify cross-referencing. This is a corrected proof. This document forms part of the archive of Galton material available at http://galton.org. Original electronic conversion by Michal Kulczycki, based on a facsimile prepared by Gavan Tredoux. Many errata were detected by Diane L. Ritter. This edition was edited, cross-checked and reformatted by Gavan Tredoux. HEREDITARY GENIUS AN INQUIRY INTO ITS LAWS AND CONSEQUENCES BY FRANCIS GALTON, F.R.S., ETC. London MACMILLAN AND CO. AND NEW YORK 1892 The Right of Translation and Reproduction is Reserved CONTENTS PREFATORY CHAPTER TO THE EDITION OF 1892.__________ VII PREFACE ______________________________________________ V CONTENTS __________________________________________ VII ERRATA _____________________________________________ VIII INTRODUCTORY CHAPTER. -

The Rarity of Realpolitik the Rarity of Brian Rathbun Realpolitik What Bismarck’S Rationality Reveals About International Politics

The Rarity of Realpolitik The Rarity of Brian Rathbun Realpolitik What Bismarck’s Rationality Reveals about International Politics Realpolitik, the pur- suit of vital state interests in a dangerous world that constrains state behavior, is at the heart of realist theory. All realists assume that states act in such a man- ner or, at the very least, are highly incentivized to do so by the structure of the international system, whether it be its anarchic character or the presence of other similarly self-interested states. Often overlooked, however, is that Real- politik has important psychological preconditions. Classical realists note that Realpolitik presupposes rational thinking, which, they argue, should not be taken for granted. Some leaders act more rationally than others because they think more rationally than others. Hans Morgenthau, perhaps the most fa- mous classical realist of all, goes as far as to suggest that rationality, and there- fore Realpolitik, is the exception rather than the rule.1 Realpolitik is rare, which is why classical realists devote as much attention to prescribing as they do to explaining foreign policy. Is Realpolitik actually rare empirically, and if so, what are the implications for scholars’ and practitioners’ understanding of foreign policy and the nature of international relations more generally? The necessity of a particular psy- chology for Realpolitik, one based on rational thinking, has never been ex- plicitly tested. Realists such as Morgenthau typically rely on sweeping and unveriªed assumptions, and the relative frequency of realist leaders is difªcult to establish empirically. In this article, I show that research in cognitive psychology provides a strong foundation for the classical realist claim that rationality is a demanding cogni- tive standard that few leaders meet. -

(2019), No. 7 1 Some Marginalia in Burnet's

Some Marginalia in Burnet’s History of My Own Time Gilbert Burnet, Bishop of Salisbury (1643–1715) had no known connection with New College during his lifetime, and very little contact with the University of Oxford. He was a graduate of the University of Aberdeen, and as a young man he had served briefly as Professor of Divinity in the University of Glasgow, but he is not remembered primarily as an academic or as a scholar. Yet, long after his death, New College Library acquired a copy of one of Burnet’s books of very considerable interest to those historians of the British Isles who specialize in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries. To explain why this is so, it is necessary first to describe Burnet, and the part he played in the affairs of the period through which he lived. I Burnet began to compile the final version of his History of My Own Time, the book in question, in about 1703, during the reign of Queen Anne. It was an exercise in contemporary history, rather than an autobiography, and it covered, in a narrative format, the years from the Restoration of 1660 to, eventually, the conclusion of the War of the Spanish Succession at the Treaty of Utrecht in 1713. An introductory chapter covered the reign of Charles I, the civil wars in Scotland and England, and the Interregnum. It was well known to contemporaries that Burnet was engaged in writing what was called his ‘Secret History’, and its publication was awaited with keen anticipation, because Burnet was a celebrated figure both in ecclesiastical affairs and in secular politics. -

The Legal History of European Reparation Claims: 1946–1953

BUXBAUM 1.17.14 1/17/2014 2:42 PM From Paris To London: The Legal History of European Reparation Claims: 1946–1953 Richard M. Buxbaum* INTRODUCTION: THE EARLY HISTORY AND WHY IT MATTERS The umbrella concept of reparations, including its compensatory as well as restitutionary aspects, regretfully remains as salient today as it was in the twentieth century. A fresh look at its history in that century, and how that history shapes today’s discourses, is warranted. This study is warranted in particular because the major focus in recent decades has been on the claims of individual victims of various atrocities and injustices—generalized as the development of international human rights law by treaty, statute, and judicial decision. One consequence of this development is that the historical primacy of the state both as the agent for its subjects and as the principally if not solely responsible actor is ever more contested. How did this shift from state responsibility and state agency over the past half-century or more occur? Considering the apparent primacy of the state in this context as World War II came to an end, do the shortcomings of the inter-state processes of the early postwar period provide a partial explanation of these later * Jackson H. Ralston Professor of International Law (Emeritus), University of California, Berkeley, School of Law. My thanks to a number of research assistants, in particular Lisa Pfitzner, Sonya Hymer, Niilana Mutama, and Rachel Anderson; my thanks also to David Caron and the late Gerald Feldman for critical reading of the manuscript and good advice. -

The Deutsche Bank and the Nazi Economic War Against the Jews: the Expropriation of Jewish-Owned Property Harold James Frontmatter More Information

Cambridge University Press 0521803292 - The Deutsche Bank and the Nazi Economic War Against the Jews: The Expropriation of Jewish-Owned Property Harold James Frontmatter More information The Deutsche Bank and the Nazi Economic War Against the Jews This book examines the role of the Deutsche Bank, Germany’s largest financial institution, in the expropriation of Jewish-owned enterprises during the Nazi dictatorship, both in the existing territories of Germany and in the area seized by the German army during World War II. The author uses new and previously unavailable materials, many from the bank’s own archives, to examine policies that led to the eventual genocide of European Jews. How far did the realization of the vicious and destruc- tive Nazi ideology depend on the acquiesence, the complicity, and the cupidity of existing economic institutions to individuals? In response to the traditional argument that business cooperation with the Nazi regime was motivated by profit, this book closely examines the behavior of the bank and its individuals to suggest other motivations. No comparable study exists of a single company’s involvement in the economic persecu- tion of the Jews in Nazi Germany. Harold James is Professor of History at Princeton University and the author of several books on German economy and society. His earlier work on the Deutsche Bank was awarded the Financial Times/Booz–Allen Book Award and the Hamilton Global Business Book of the Year Award in 1996. © Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press -

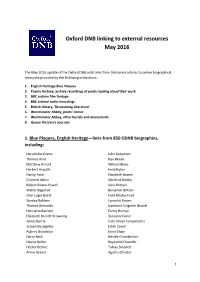

Oxford DNB Linking to External Resources May 2016

Oxford DNB linking to external resources May 2016 The May 2016 update of the Oxford DNB adds links from Dictionary articles to online biographical resources provided by the following institutions: 1. English Heritage Blue Plaques 2. Poetry Archive, archive recordings of poets reading aloud their work 3. BBC archive film footage 4. BBC archive radio recordings 5. British Library, ‘Discovering Literature’ 6. Westminster Abbey, poets’ corner 7. Westminster Abbey, other burials and monuments 8. Queen Victoria’s Journals 1. Blue Plaques, English Heritage—links from 850 ODNB biographies, including: Harold Abrahams John Betjeman Thomas Arne Nye Bevan Matthew Arnold William Blake Herbert Asquith Enid Blyton Nancy Astor Elizabeth Bowen Clement Attlee Winifred Holtby Robert Paden-Powell Vera Brittain Walter Bagehot Benjamin Britten John Logie Baird Ford Madox Ford Stanley Baldwin Lancelot Brown Thomas Barnardo Isambard Kingdom Brunel Henrietta Barnett Fanny Burney Elizabeth Barrett Browning Giovanni Canal James Barrie Cato Street Conspirators Joseph Bazalgette Edith Cavell Aubrey Beardsley Ernst Chain Harry Beck Neville Chamberlain Hilaire Belloc Raymond Chandler Hector Berlioz Tobias Smollett Annie Besant Agatha Christie 1 Winston Churchill Arthur Conan Doyle William Wilberforce John Constable Wells Coates Learie Constantine Wilkie Collins Noel Coward Ivy Compton-Burnett Thomas Daniel Charles Darwin Mohammed Jinnah Francisco de Miranda Amy Johnson Thomas de Quincey Celia Johnson Daniel Defoe Samuel Johnson Frederic Delius James Joyce Charles Dickens -

The Papers of Ueen Victoria on Foreign Affairs

A Guide to the Microfilm Edition of The Papers of ueen QVictoria on Foreign Affairs Part 4: Portugal and Spain, 1841-1900 UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA A Guide to the Microfilm Edition of Files from the Royal Archives, Windsor Castle THE PAPERS OF QUEEN VICTORIA ON FOREIGN AFFAIRS Edited by Kenneth Bourne Part 4: Spain and Portugal, 1841-1900 Guide compiled by David Loving A microfilm project of UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA An Imprint of CIS 4520 East-West Highway • Bethesda, MD 20814-3389 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Victoria, Queen of Great Britain, 1819-1901. The papers of Queen Victoria on foreign affairs [microform] edited by Kenneth Bourne. microfilm reels. — (Files from the Royal Archives, Windsor Castle) Contents: Pt. 1. Russia and Eastern Europe, 1846-1900 Pt. 6. Greece, 1847-1863. ISBN 1-55655-187-8 (microfilm) 1. Great Britain ~ Foreign relations — 1837-1901 ~ Sources — Manuscripts ~ Microform catalogs. I. Bourne, Kenneth. II. Hydrick, Blair. HI. Title. IV. Series. [DA550.V] 327.41-dc20 92-9780 CIP Copyright Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth n 1993. This is a reproduction of a series of documents preserved in the Royal Archives at Windsor Castle, published by gracious permission of Her Majesty the Queen. No further photographic reproduction of the microfilm may be made without the permission of University Publications of America. Copyright © 1993 Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II. All rights reserved. ISBN 1-55655-187-8. TABLE OF CONTENTS General Introduction v Introduction: Part 4: Spain and Portugal, 1841-1900 xii Reel Index Reell Spanish Marriage Question, 1841-1846, Vol. J.43 1 Spanish Marriage Question, 1846, Vol. -

ARTISTS MAKE US WHO WE ARE the ANNUAL REPORT of the PENNSYLVANIA ACADEMY of the FINE ARTS Fiscal Year 2012-13 1 PRESIDENT’S LETTER

ARTISTS MAKE US WHO WE ARE THE ANNUAL REPORT OF THE PENNSYLVANIA ACADEMY OF THE FINE ARTS FISCAL YEAR 2012-13 1 PRESIDENT’S LETTER PAFA’s new tagline boldly declares, “We Make Artists.” This is an intentionally provocative statement. One might readily retort, “Aren’t artists born to their calling?” Or, “Don’t artists become artists through a combination of hard work and innate talent?” Well, of course they do. At the same time, PAFA is distinctive among the many art schools across the United States in that we focus on training fine artists, rather than designers. Most art schools today focus on this latter, more apparently utilitarian career training. PAFA still believes passionately in the value of art for art’s sake, art for beauty, art for political expression, art for the betterment of humanity, art as a defin- ing voice in American and world civilization. The students we attract from around the globe benefit from this passion, focus, and expertise, and our Annual Student Exhibition celebrates and affirms their determination to be artists. PAFA is a Museum as well as a School of Fine Arts. So, you may ask, how does the Museum participate in “making artists?” Through its thoughtful selection of artists for exhibition and acquisition, PAFA’s Museum helps to interpret, evaluate, and elevate artists for more attention and acclaim. Reputation is an important part of an artist’s place in the ecosystem of the art world, and PAFA helps to reinforce and build the careers of artists, emerging and established, through its activities. PAFA’s Museum and School also cultivate the creativity of young artists. -

Penn's 2021 Commencement Speaker and Honorary Degree

UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA Tuesday March 16, 2021 Volume 67 Number 30 www.upenn.edu/almanac Penn’s 2021 Commencement Speaker and Honorary Degree Recipients Alumna and philanthropist Laurene Powell Jobs will be Penn’s Commencement Speaker at the 2021 University of Pennsylvania Com- mencement on Monday, May 17. Medha Narvekar, Penn’s Vice President and University Secretary, has announced the 2021 honorary degree recipients and the Commence- ment Speaker for the University of Pennsylva- nia. The Office of the University Secretary man- ages the honorary degree selection process and University Commencement. Due to pandemic health restrictions, this year’s Commencement ceremony will be limit- ed to graduating seniors who have been partici- pating in the University’s COVID-19 screening Laurene Powell Jobs Elizabeth Alexander Frances Arnold David L. Cohen procedures. Family and friends will be able to watch a livestream of the celebration and a re- cording will be posted to the University’s web- site. Other 2021 Penn honorary degree recipients are Elizabeth Alexander, Frances Arnold, Da- vid L. Cohen, Joy Harjo, David Miliband, John Williams, and Janet Yellen. More Commencement Information in this Issue: See page 2 for an announcement from the President, Provost and EVP with specific details about the ceremony. See pages 6-7 for detailed bios of the honorary degree recipients. Joy Hario David Miliband John Williams Janet Yellen Kevin Johnson: Penn Integrates Knowledge University Professor Margo Brooks-Carthon and Heath President Amy Gutmann and Provost Wendell prove the health of individuals and communities,” Schmidt: Endowed Chairs in Pritchett announced the appointment of Kevin said President Gutmann. -

The Historical Journal I S T O

VOL 57 NO 4 DECEMBER 2014 0018 246X T H E H THE HISTORICAL JOURNAL I S T O R VOL 57 NO 4 DECEMBER 2014 I CONTENTS C A L RTICLES A J O ROBERT HARKINS Elizabethan puritanism and the politics of memory in U post-Marian England 899 R KATE DAVISON Occasional politeness and gentlemen's laughter in 18 th C England 921 N RHYS JONES Beethoven and the sound of revolution in Vienna, 1792–1814 947 A L MICHAEL TAYLOR Conservative political economy and the problem of THE colonial slavery, 1823–1833 973 ANDREKOS VARNAVA French and British post-war imperial agendas and forging an Armenian homeland after the genocide: the formation of the Légion d’Orient in October 1916 997 GARY LOVE The periodical press and the intellectual culture of V Conservatism in interwar Britain 1027 O L DAN TAMIR From a fascist’s notebook to the principles of rebirth: HISTORICAL 5 the desire for social integration in Hebrew fascism, 1928–1942 1057 7 EMMA L. J ONES AND NEIL PEMBERTON Ten Rillington Place and the changing politics of abortion in modern Britain 1085 N O PATRICK ANDELIC Daniel Patrick Moynihan, the 1976 New York Senate race, and the struggle to define American liberalism 1111 4 D E JOURNAL H ISTORIOGRAPHICAL R EVIEWS C RONALD HUTTON The making of the early modern British fairy tradition 1135 E M ABIGAIL GREEN Humanitarianism in nineteenth-century context: religious, B gendered, national 1157 E R 2 0 1 4 ® Cambridge Journals Online MIX For further information about this journal Paper from please go to the journal website at: responsible sources journals.cambridge.org/his ® Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. -

For Those Royalists Disappointed by Charles II's Failure to Reward Them

1 The earls of Derby and the opposition to their estate bills in parliament, 1660-92: some new manuscript sources By Charles Littleton, History of Parliament Trust Abstract: The bills introduced in 1660-62 by Charles Stanley, 8th earl of Derby, to reclaim his property conveyed by legal procedures to other proprietors during the Interregnum are well-known to students of the Restoration, as their ultimate defeat is seen as evidence of the royal government's wish to enforce 'indemnity and oblivion' after the civil war. The leading members of the House of Lords opposed to the bill of 1661-2 can be gauged by the protest against its passage on 6 February 1662, which has been readily available to students to consult since the 18th-century publication of the Lords Journals. A number of manuscript lists of the protesters against the bill's passage reveal that the opposition to the bill was even more extensive and politically varied than the protest in the Journal suggests, which raises questions of why the printed protest is so incomplete. A voting forecast drawn up by William Stanley, 9th earl of Derby, in 1691 further reminds us of the often neglected point that the Stanleys continued to submit bills for the resumption of their hereditary lands well after the disappointment of 1662. Derby's manuscript calculations, though ultimately highly inaccurate, reveal much about how this particular peer envisaged the forces ranged for and against the claims of an old civil war royalist family, a good forty years after the loss of their land.