Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Appendix – Prime Ministers of the Nineteenth Century

Appendix – Prime Ministers of the Nineteenth Century Total Age at first Dates of time as Name Party appointment Ministries Premier 1. William Pitt, born Tory 24 years, 19 Dec. 1783–14 18 years, 28 May 1759, died 205 days March 1801, 343 days 23 Jan. 1806, 10 May 1804–23 unmarried. Jan. 1806 2. Henry Addington, Tory 43 years, 17 March 3 years, 1st Viscount Sidmouth, 291 days 1801–10 54 days born 30 May 1757, May 1804 died 15 Feb. 1844, married (1) Ursula Hammond, 17 Sep. 1781 (2) Mary Anne Townsend, 1823, 4 sons, 4 daughters 3. William Grenville, 1st Whig 46 years, 11 Feb. 1806–25 1 year, Baron Grenville, born 110 days March 1807 42 days 24 Oct. 1759, died 12 Jan. 1834, married Anne Pitt, 18 Jun. 1792, no children 4. William Cavendish- Whig, 44 years, 2 April 1783–18 3 years, Bentinck, 3rd Duke of then Tory 353 days Dec. 1783, 82 days Portland, born 14 April 31 March 1807–4 1738, died 30 Oct; 1809, Oct. 1809 married Lady Dorothy Cavendish, 8 Nov. 1766, 4 sons, 2 daughters 5. Spencer Perceval, born Tory 46 years, 4 Oct. 1809–11 2 years, 1 Nov. 1762, died 11 May 338 days May 1812 221 days 1812, married Jane Spencer-Wilson, 10 Aug. 1790, 6 sons, 6 daughters Continued 339 340 Appendix Appendix: Continued Total Age at first Dates of time as Name Party appointment Ministries Premier 6. Robert Banks Tory 42 years, 8 Jun. 1812–9 14 years, Jenkinson, 2nd Earl 1 day April 1827 305 days of Liverpool, born 7 Jun. -

The Life of William Ewart Gladstone (Vol 2 of 3) by John Morley

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Life of William Ewart Gladstone (Vol 2 of 3) by John Morley This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at http://www.gutenberg.org/license Title: The Life of William Ewart Gladstone (Vol 2 of 3) Author: John Morley Release Date: May 24, 2010, 2009 [Ebook 32510] Language: English ***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE LIFE OF WILLIAM EWART GLADSTONE (VOL 2 OF 3)*** The Life Of William Ewart Gladstone By John Morley In Three Volumes—Vol. II. (1859-1880) Toronto George N. Morang & Company, Limited Copyright, 1903 By The Macmillan Company Contents Book V. 1859-1868 . .2 Chapter I. The Italian Revolution. (1859-1860) . .2 Chapter II. The Great Budget. (1860-1861) . 21 Chapter III. Battle For Economy. (1860-1862) . 49 Chapter IV. The Spirit Of Gladstonian Finance. (1859- 1866) . 62 Chapter V. American Civil War. (1861-1863) . 79 Chapter VI. Death Of Friends—Days At Balmoral. (1861-1884) . 99 Chapter VII. Garibaldi—Denmark. (1864) . 121 Chapter VIII. Advance In Public Position And Other- wise. (1864) . 137 Chapter IX. Defeat At Oxford—Death Of Lord Palmer- ston—Parliamentary Leadership. (1865) . 156 Chapter X. Matters Ecclesiastical. (1864-1868) . 179 Chapter XI. Popular Estimates. (1868) . 192 Chapter XII. Letters. (1859-1868) . 203 Chapter XIII. Reform. (1866) . 223 Chapter XIV. The Struggle For Household Suffrage. (1867) . 250 Chapter XV. -

The Making of White Australia

The making of White Australia: Ruling class agendas, 1876-1888 Philip Gavin Griffiths A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The Australian National University December 2006 I declare that the material contained in this thesis is entirely my own work, except where due and accurate acknowledgement of another source has been made. Philip Gavin Griffiths Page v Contents Acknowledgements ix Abbreviations xiii Abstract xv Chapter 1 Introduction 1 A review of the literature 4 A ruling class policy? 27 Methodology 35 Summary of thesis argument 41 Organisation of the thesis 47 A note on words and comparisons 50 Chapter 2 Class analysis and colonial Australia 53 Marxism and class analysis 54 An Australian ruling class? 61 Challenges to Marxism 76 A Marxist theory of racism 87 Chapter 3 Chinese people as a strategic threat 97 Gold as a lever for colonisation 105 The Queensland anti-Chinese laws of 1876-77 110 The ‘dangers’ of a relatively unsettled colonial settler state 126 The Queensland ruling class galvanised behind restrictive legislation 131 Conclusion 135 Page vi Chapter 4 The spectre of slavery, or, who will do ‘our’ work in the tropics? 137 The political economy of anti-slavery 142 Indentured labour: The new slavery? 149 The controversy over Pacific Islander ‘slavery’ 152 A racially-divided working class: The real spectre of slavery 166 Chinese people as carriers of slavery 171 The ruling class dilemma: Who will do ‘our’ work in the tropics? 176 A divided continent? Parkes proposes to unite the south 183 Conclusion -

Biographical Appendix

Biographical Appendix The following women are mentioned in the text and notes. Abney- Hastings, Flora. 1854–1887. Daughter of 1st Baron Donington and Edith Rawdon- Hastings, Countess of Loudon. Married Henry FitzAlan Howard, 15th Duke of Norfolk, 1877. Acheson, Theodosia. 1882–1977. Daughter of 4th Earl of Gosford and Louisa Montagu (daughter of 7th Duke of Manchester and Luise von Alten). Married Hon. Alexander Cadogan, son of 5th Earl of Cadogan, 1912. Her scrapbook of country house visits is in the British Library, Add. 75295. Alten, Luise von. 1832–1911. Daughter of Karl von Alten. Married William Montagu, 7th Duke of Manchester, 1852. Secondly, married Spencer Cavendish, 8th Duke of Devonshire, 1892. Grandmother of Alexandra, Mary, and Theodosia Acheson. Annesley, Katherine. c. 1700–1736. Daughter of 3rd Earl of Anglesey and Catherine Darnley (illegitimate daughter of James II and Catherine Sedley, Countess of Dorchester). Married William Phipps, 1718. Apsley, Isabella. Daughter of Sir Allen Apsley. Married Sir William Wentworth in the late seventeenth century. Arbuthnot, Caroline. b. c. 1802. Daughter of Rt. Hon. Charles Arbuthnot. Stepdaughter of Harriet Fane. She did not marry. Arbuthnot, Marcia. 1804–1878. Daughter of Rt. Hon. Charles Arbuthnot. Stepdaughter of Harriet Fane. Married William Cholmondeley, 3rd Marquess of Cholmondeley, 1825. Aston, Barbara. 1744–1786. Daughter and co- heir of 5th Lord Faston of Forfar. Married Hon. Henry Clifford, son of 3rd Baron Clifford of Chudleigh, 1762. Bannister, Henrietta. d. 1796. Daughter of John Bannister. She married Rev. Hon. Brownlow North, son of 1st Earl of Guilford, 1771. Bassett, Anne. Daughter of Sir John Bassett and Honor Grenville. -

Australian Indigenous Petitions

Australian Indigenous Petitions: Emergence and Negotiations of Indigenous Authorship and Writings Chiara Gamboz Dissertation Submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of New South Wales School of Arts and Media Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences October 2012 ORIGINALITY STATEMENT 'l hereby declare that this submission is my own work and to the best of my knowledge it contains no materials previously published or written by another person, or substantial proportions of material which have been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma at UNSW or any other educational institution, except where due acknowledgement is made in the thesis. Any contribution made to the research by others, with whom I have worked at UNSW or elsewhere, is explicitly acknowledged in the thesis. I also declare that the intellectual content of this thesis is the product of my own work, except to the extent that assistance from others in the proiect's design and conception or in style, presentation and linguistic expression is acknowledged.' Signed 5 o/z COPYRIGHT STATEMENT 'l hereby grant the University of New South Wales or its agents the right to archive and to make available my thesis or digsertation in whole or part in the Univercity libraries in all forms of media, now or here after known, subject to the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. I retain all proprietary rights, such as patent rights. I also retain the right to use in future works (such as articles or books) all or part of this thesis or dissertiation. -

Hereditary Genius Francis Galton

Hereditary Genius Francis Galton Sir William Sydney, John Dudley, Earl of Warwick Soldier and knight and Duke of Northumberland; Earl of renown Marshal. “The minion of his time.” _________|_________ ___________|___ | | | | Lucy, marr. Sir Henry Sydney = Mary Sir Robt. Dudley, William Herbert Sir James three times Lord | the great Earl of 1st E. Pembroke Harrington Deputy of Ireland.| Leicester. Statesman and __________________________|____________ soldier. | | | | Sir Philip Sydney, Sir Robert, Mary = 2d Earl of Pembroke. Scholar, soldier, 1st Earl Leicester, Epitaph | courtier. Soldier & courtier. by Ben | | Johnson | | | Sir Robert, 2d Earl. 3d Earl Pembroke, “Learning, observation, Patron of letters. and veracity.” ____________|_____________________ | | | Philip Sydney, Algernon Sydney, Dorothy, 3d Earl, Patriot. Waller's one of Cromwell's Beheaded, 1683. “Saccharissa.” Council. First published in 1869. Second Edition, with an additional preface, 1892. Fifith corrected proof of the first electronic edition, 2019. Based on the text of the second edition. The page numbering and layout of the second edition have been preserved, as far as possible, to simplify cross-referencing. This is a corrected proof. This document forms part of the archive of Galton material available at http://galton.org. Original electronic conversion by Michal Kulczycki, based on a facsimile prepared by Gavan Tredoux. Many errata were detected by Diane L. Ritter. This edition was edited, cross-checked and reformatted by Gavan Tredoux. HEREDITARY GENIUS AN INQUIRY INTO ITS LAWS AND CONSEQUENCES BY FRANCIS GALTON, F.R.S., ETC. London MACMILLAN AND CO. AND NEW YORK 1892 The Right of Translation and Reproduction is Reserved CONTENTS PREFATORY CHAPTER TO THE EDITION OF 1892.__________ VII PREFACE ______________________________________________ V CONTENTS __________________________________________ VII ERRATA _____________________________________________ VIII INTRODUCTORY CHAPTER. -

(2019), No. 7 1 Some Marginalia in Burnet's

Some Marginalia in Burnet’s History of My Own Time Gilbert Burnet, Bishop of Salisbury (1643–1715) had no known connection with New College during his lifetime, and very little contact with the University of Oxford. He was a graduate of the University of Aberdeen, and as a young man he had served briefly as Professor of Divinity in the University of Glasgow, but he is not remembered primarily as an academic or as a scholar. Yet, long after his death, New College Library acquired a copy of one of Burnet’s books of very considerable interest to those historians of the British Isles who specialize in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries. To explain why this is so, it is necessary first to describe Burnet, and the part he played in the affairs of the period through which he lived. I Burnet began to compile the final version of his History of My Own Time, the book in question, in about 1703, during the reign of Queen Anne. It was an exercise in contemporary history, rather than an autobiography, and it covered, in a narrative format, the years from the Restoration of 1660 to, eventually, the conclusion of the War of the Spanish Succession at the Treaty of Utrecht in 1713. An introductory chapter covered the reign of Charles I, the civil wars in Scotland and England, and the Interregnum. It was well known to contemporaries that Burnet was engaged in writing what was called his ‘Secret History’, and its publication was awaited with keen anticipation, because Burnet was a celebrated figure both in ecclesiastical affairs and in secular politics. -

Russell in the Lords

rticles RUSSELL IN THE LORDS K W History / U. of Georgia Athens, –, @.. Bertrand Russell sat in the House of Lords as the third Earl Russell from to . In these nearly years as a Labour peer, Russell proved to be a fitful attender and infrequent participant in the upper house—speaking only six times. This paper examines each of these interventions—studying not just the speeches themselves but also their genesis and impact within Parliament and without. Of all the controversial and important foreign and domestic issues faced by Parlia- ment over these four decades, it was matters of peace and war which prompted Russell to take advantage of his hereditary position and, more importantly, of the national forum which the Lords’ chamber provided him. ertrand Russell’s aristocratic lineage was central both to his own self-understanding and to the image his contemporaries—English Band non-English alike—had of him over the course of his im- mensely long life. Although his patrician background added an unde- niable exoticism to Russell’s reputation abroad, within Britain it was central to his social position as well as to cultural expectation. No matter how great his achievement in philosophy or how wide his notoriety in politics, Russell’s reputation—indeed, his very identity—possessed an inescapably aristocratic component, one best summed up by Noel Annan’s celebrated judgment that alone of twentieth-century English- russell: the Journal of Bertrand Russell Studies n.s. (winter –): – The Bertrand Russell Research Centre, McMaster U. - men Russell belonged to an aristocracy of talent as well as of birth. -

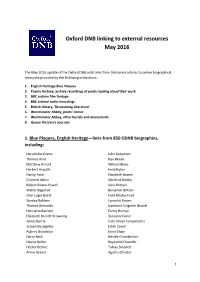

Oxford DNB Linking to External Resources May 2016

Oxford DNB linking to external resources May 2016 The May 2016 update of the Oxford DNB adds links from Dictionary articles to online biographical resources provided by the following institutions: 1. English Heritage Blue Plaques 2. Poetry Archive, archive recordings of poets reading aloud their work 3. BBC archive film footage 4. BBC archive radio recordings 5. British Library, ‘Discovering Literature’ 6. Westminster Abbey, poets’ corner 7. Westminster Abbey, other burials and monuments 8. Queen Victoria’s Journals 1. Blue Plaques, English Heritage—links from 850 ODNB biographies, including: Harold Abrahams John Betjeman Thomas Arne Nye Bevan Matthew Arnold William Blake Herbert Asquith Enid Blyton Nancy Astor Elizabeth Bowen Clement Attlee Winifred Holtby Robert Paden-Powell Vera Brittain Walter Bagehot Benjamin Britten John Logie Baird Ford Madox Ford Stanley Baldwin Lancelot Brown Thomas Barnardo Isambard Kingdom Brunel Henrietta Barnett Fanny Burney Elizabeth Barrett Browning Giovanni Canal James Barrie Cato Street Conspirators Joseph Bazalgette Edith Cavell Aubrey Beardsley Ernst Chain Harry Beck Neville Chamberlain Hilaire Belloc Raymond Chandler Hector Berlioz Tobias Smollett Annie Besant Agatha Christie 1 Winston Churchill Arthur Conan Doyle William Wilberforce John Constable Wells Coates Learie Constantine Wilkie Collins Noel Coward Ivy Compton-Burnett Thomas Daniel Charles Darwin Mohammed Jinnah Francisco de Miranda Amy Johnson Thomas de Quincey Celia Johnson Daniel Defoe Samuel Johnson Frederic Delius James Joyce Charles Dickens -

List of Fellows of the Royal Society 1660 – 2007

Library and Information Services List of Fellows of the Royal Society 1660 – 2007 A - J Library and Information Services List of Fellows of the Royal Society 1660 - 2007 A complete listing of all Fellows and Foreign Members since the foundation of the Society A - J July 2007 List of Fellows of the Royal Society 1660 - 2007 The list contains the name, dates of birth and death (where known), membership type and date of election for all Fellows of the Royal Society since 1660, including the most recently elected Fellows (details correct at July 2007) and provides a quick reference to around 8,000 Fellows. It is produced from the Sackler Archive Resource, a biographical database of Fellows of the Royal Society since its foundation in 1660. Generously funded by Dr Raymond R Sackler, Hon KBE, and Mrs Beverly Sackler, the Resource offers access to information on all Fellows of the Royal Society since the seventeenth century, from key characters in the evolution of science to fascinating lesser- known figures. In addition to the information presented in this list, records include details of a Fellow’s education, career, participation in the Royal Society and membership of other societies. Citations and proposers have been transcribed from election certificates and added to the online archive catalogue and digital images of the certificates have been attached to the catalogue records. This list is also available in electronic form via the Library pages of the Royal Society web site: www.royalsoc.ac.uk/library Contributions of biographical details on any Fellow would be most welcome. -

After the 'German Civil War' of 1866: Building The

Decades of Reconstruction Postwar Societies, State-Building, and International Relations from the Seven Years’ War to the Cold War Edited by UTE PLANERT University of Cologne JAMES RETALLACK University of Toronto GERMAN HISTORICAL INSITUTE Washington, D.C. and Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. University of Toronto, on 23 May 2020 at 14:03:03, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781316694091 University Printing House, Cambridge cb2 8bs, United Kingdom Cambridge University Press is part of the University of Cambridge. It furthers the University’s mission by disseminating knowledge in the pursuit of education, learning and research at the highest international levels of excellence. www.cambridge.org Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9781107165748 © Cambridge University Press 2017 This publication is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published 2017 Printed in the United States of America by Sheridan Books, Inc. A catalogue record for this publication is available from the British Library isbn 978-1-107-16574-8 Hardback isbn 978-1-316-61708-3 Paperback Cambridge University Press has no responsibility for the persistence or accuracy of URLs for external or third-party Internet websites referred to in this publication and does not guarantee that any content on such websites is, or will remain, accurate or appropriate. Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. University of Toronto, on 23 May 2020 at 14:03:03, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. -

Rosse Papers Summary List: 17Th Century Correspondence

ROSSE PAPERS SUMMARY LIST: 17TH CENTURY CORRESPONDENCE A/ DATE DESCRIPTION 1-26 1595-1699: 17th-century letters and papers of the two branches of the 1871 Parsons family, the Parsonses of Bellamont, Co. Dublin, Viscounts Rosse, and the Parsonses of Parsonstown, alias Birr, King’s County. [N.B. The whole of this section is kept in the right-hand cupboard of the Muniment Room in Birr Castle. It has been microfilmed by the Carroll Institute, Carroll House, 2-6 Catherine Place, London SW1E 6HF. A copy of the microfilm is available in the Muniment Room at Birr Castle and in PRONI.] 1 1595-1699 Large folio volume containing c.125 very miscellaneous documents, amateurishly but sensibly attached to its pages, and referred to in other sub-sections of Section A as ‘MSS ii’. This volume is described in R. J. Hayes, Manuscript Sources for the History of Irish Civilisation, as ‘A volume of documents relating to the Parsons family of Birr, Earls of Rosse, and lands in Offaly and property in Birr, 1595-1699’, and has been microfilmed by the National Library of Ireland (n.526: p. 799). It includes letters of c.1640 from Rev. Richard Heaton, the early and important Irish botanist. 2 1595-1699 Late 19th-century, and not quite complete, table of contents to A/1 (‘MSS ii’) [in the handwriting of the 5th Earl of Rosse (d. 1918)], and including the following entries: ‘1. 1595. Elizabeth Regina, grant to Richard Hardinge (copia). ... 7. 1629. Agreement of sale from Samuel Smith of Birr to Lady Anne Parsons, relict of Sir Laurence Parsons, of cattle, “especially the cows of English breed”.