Conference Proceedings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

31/08/2018 1 of 8 ROSTRUM VOICE of YOUTH NATIONAL FINALISTS

ROSTRUM VOICE OF YOUTH NATIONAL FINALISTS Year Nat Final Convenor Zone Coordinator Junior Finalist School Place Senior Finalist School Place National Coordinator 1975 Tom Trebilco ACT Tom Trebilco Fiona Tilley Belconnen HS 1 Linzi Jones 1975 NSW 1975 QLD Vince McHugh Sue Stevens St Monica's College Cairns Michelle Barker 1975 SA NA NA NA Sheryn Pitman Methodist Ladies College 2 1975 TAS Mac Blackwood Anthony Ackroyd St Virgils College, Hobart 1 1975 VIC 1975 WA Year Nat Final Convenor Zone Coordinator Junior Finalist School Place Senior Finalist School Place 1976 Tom Trebilco? ACT Tom Trebilco? Tim Hayden Telopea Park HS 1 (tie) 1976 NSW 1976 QLD Vince McHugh Michelle Morgan Brigadine Convent Margaret Paton All Hallows School Brisbane 1976 SA NA NA NA NA NA 1976 TAS Mac Blackwood Lisa Thompson Oakburn College 1 (tie) 1976 VIC 1976 WA Paul Donovan St Louis School 1 Year Nat Final Convenor Zone Coordinator Junior Finalist School Place Senior Finalist School Place 1977 ACT Michelle Regan (sub) Belconnen HS 1977 NSW John White Kerrie Mengerson Coonabarabran HS 1 Sonia Anderson Francis Greenway HS,Maitland 1 1977 QLD Mervyn Green Susan Burrows St Margarets Clayfield Anne Frawley Rockhampton 1977 SA NA NA NA NA NA 1977 TAS Mac Blackwood Julie Smith Burnie High Gabrielle Bennett Launceston 1977 Richard Smillie VIC Pat Taylor Linda Holland St Anne's Warrnambool 3 Kelvin Bicknell Echuca Technical 1977 WA David Johnston Mark Donovan John XX111 College 2 Fiona Gauntlett John XX111 College 2 Year Nat Final Convenor Zone Coordinator Junior Finalist -

Top-12-Students-Announced.Pdf

Minister for Education and Minister for Industrial Relations The Honourable Grace Grace Queensland’s top Year 12 graduates announced Education Minister Grace Grace has today congratulated the state’s top Year 12 graduates from the class of 2018 at the Queensland Certificate of Education (QCE) Achievement Awards. “These annual awards are a fantastic opportunity to recognise the hard work and achievement of our top students, as well as the teachers and families who supported them,” Ms Grace said. “In 2018, close to 49,000 young Queenslanders received a QCE. They have now turned their focus to entering university, starting a trade or moving straight into the workforce,” Ms Grace said. Ms Grace said the top award of Outstanding Academic Achiever went to Maya Lamont who attended Indooroopilly State High School. Maya received a certificate, trophy, and $5000. “Maya’s extraordinary Year 12 results placed her ahead of more than 51,000 of her peers,” Ms Grace said. “She achieved exceptionally highly in all her school subjects, the Queensland Core Skills Test, tertiary entrance ranking, and in a philosophy subject at university. “Maya hopes to work in environmental law or government in the future and advocate for causes she’s passionate about. “This year Maya will study Arts and law at The University of Queensland. “I congratulate Maya and commend the wonderfully supportive learning environment at Indooroopilly State High School that helped her to flourish.” QCAA chief executive officer Chris Rider said the awards highlighted the strength of senior schooling in Queensland. “The award winners attended 23 different state and non-state schools,” Mr Rider said. -

Albion Park Adams, Ashlyn 15 1 Westfields S Adeniran, Shola 15 2

Sydney Olympic Park 2 - Site License Hy-Tek's MEET MANAGER 4:35 PM 17/09/2019 Page 1 2019 NSW All Schools Championships - 26/09/2019 to 29/09/2019 Track and Field Championships SOPAC, Homebush Performance List Event 226 Girls 100 Meter Sprint 15 years Prelims Saturday 28/09/2019 - 12:40 PM Comp# Name Age Team Seed Time 1 Adams, Ashlyn 15 Albion Park 2 Adeniran, Shola 15 Westfields S 3 Adra, Amani 15 East Hills G 4 Ahmad, Salam 15 Meridan Stra 5 Beaven, Jade 15 St Josephs E 6 Bowley, Sophie 15 Temora High 7 Burgers-Rebec, Hunter 15 Emmaus Catho 8 Clancy, Charlotte 15 Roseville College 9 Fichardt, Georgia 15 Abbotsleigh 10 Flanagan, Lucy 15 Bethany Coll 11 Garnett, Ella 15 Plc Sydney Croydon 12 Gill, Imogen 15 St Vincents 13 Hamilton, Erin 15 Central Coas 14 Harrison (T/F37), Lainee 15 Hunter Sports High 15 Jenkins, Alyssa 15 Coffs Harbour High 16 Lammers, Zara 15 Kirrawee High 17 Latimer, Sophie 14 Elderslie High 18 Lee, Regina 15 Trinity Grammar 19 Lee, Regina 15 Meridan Stra 20 Martin, Alannah 15 St Agnes Hig 21 McAndrew, Adria 15 Riverside Gi 22 Moore, Kailee 15 Holy Spirit 23 Parkes, Giorgi 15 St Catherine 24 Percival, Lauren 15 Ulladulla High 25 Plummer, Amalia 15 Magdalene Ca Sydney Olympic Park 2 - Site License Hy-Tek's MEET MANAGER 4:35 PM 17/09/2019 Page 2 2019 NSW All Schools Championships - 26/09/2019 to 29/09/2019 Track and Field Championships SOPAC, Homebush Performance List Event 226 .. -

4Th Apr 2011

LavallaCatholicCollege 4 April 2011 From the Principal Staff News Out of his infinite glory, Dear parents, teachers and students You will remember that Mr Marco DiCesare We are entering into our last week of term will be Acting Principal for the duration of may he give you the power and we are all anticipating the holiday break. term 2 and Ms Lee McKenzie Acting Campus through his Spirit for your This year we will celebrate Easter just be- Director of Kildare. I wish them all the best fore we return for term 2, hence the public in their new roles and thank them for their hidden self to grow strong, holidays for Easter and Anzac Day surround- generosity in accepting these new positions. so that Christ may live in ing that week. School resumes on Wednes- We welcome new and returning members of your heart through faith… day 27th April for both students and staff. staff to our community in Term 2: Ephesians 3: 16 We have had a very busy term and teachers ST PAUL’S have offered our students many opportunities Mr John de Souza-Daw – Humanities to extend their skills and to broaden their ex- Ms Liz Krutli – Science and Mathematics God of my potential, periences. From leadership days, camps and Mrs Ellen Fredrickson – Technology retreats, numerous sporting activities and oth- Materials (food) you show such pa- er competitions there was rarely a day when Mr Dwayne Tibbals (Sports and Camp co- there wasn’t a scheduled activity on our calen- ordinator) tience towards me. dar. We have received positive feedback from KILDARE parents through the Learner Advisor meetings Mr Ernie rijs – Humanities and rE in terms of student motivation and focus and Mr Sunil nand – Geography and rE I seem to inch I would particularly like to acknowledge the RETURNING FROM LONG SERVICE LEAVE care that our teachers display on a daily basis Mr Mark Judd & Mr Bill Eagle forward to our students. -

Annual Report

Our Lady of Lourdes Primary School, Sunnybank ANNUAL REPORT 2018 As a Catholic community of faith, Brisbane Catholic Education inspires students with a love of learning and a heart of hope, empowering them to shape and enrich our world. 1 Contact information School name: Our Lady of Lourdes Primary School Postal address: PO Box 439, SUNNYBANK, QLD, 4109 Phone: (07) 3345 0700 Email: [email protected] School website: www.ourladyoflourdes.qld.edu.au Contact Person: Michael McInerney - Acting Principal Vision, Mission and Values Vision Draft: As a community of faith, Our Lady of Lourdes Catholic School, Sunnybank inspires students to be lifelong, independent faith filled learners. This foundation empowers our students to take their place as purposeful people with the courage, wisdom and will to shape and enrich our world. Mission Our Lady of Lourdes Catholic Primary School fosters the values and teachings of Jesus Christ. These values are embedded in the Mary MacKillop Charism and honour our school’s patron Saint, Our Lady of Lourdes. Our Lady of Lourdes School is an inclusive community, providing an holistic education of body, mind and spirit. We aspire to teach, challenge and transform in our welcoming and nurturing learning environment. This is achieved through active and positive partnerships between students, staff, families, parish and the wider community. In striving for excellence we aim to inspire students to be responsible for their learning and to reach their full potential as lifelong learners. Our Lady of Lourdes School offers a Catholic perspective within the community. We acknowledge the importance of justice, demonstrated through compassion and are committed to being a positive influence in the lives of all. -

Certified School List MM-DD-YY.Xlsx

Updated SEVP Certified Schools January 26, 2017 SCHOOL NAME CAMPUS NAME F M CITY ST CAMPUS ID "I Am" School Inc. "I Am" School Inc. Y N Mount Shasta CA 41789 ‐ A ‐ A F International School of Languages Inc. Monroe County Community College Y N Monroe MI 135501 A F International School of Languages Inc. Monroe SH Y N North Hills CA 180718 A. T. Still University of Health Sciences Lipscomb Academy Y N Nashville TN 434743 Aaron School Southeastern Baptist Theological Y N Wake Forest NC 5594 Aaron School Southeastern Bible College Y N Birmingham AL 1110 ABC Beauty Academy, INC. South University ‐ Savannah Y N Savannah GA 10841 ABC Beauty Academy, LLC Glynn County School Administrative Y N Brunswick GA 61664 Abcott Institute Ivy Tech Community College ‐ Y Y Terre Haute IN 6050 Aberdeen School District 6‐1 WATSON SCHOOL OF BIOLOGICAL Y N COLD SPRING NY 8094 Abiding Savior Lutheran School Milford High School Y N Highland MI 23075 Abilene Christian Schools German International School Y N Allston MA 99359 Abilene Christian University Gesu (Catholic School) Y N Detroit MI 146200 Abington Friends School St. Bernard's Academy Y N Eureka CA 25239 Abraham Baldwin Agricultural College Airlink LLC N Y Waterville ME 1721944 Abraham Joshua Heschel School South‐Doyle High School Y N Knoxville TN 184190 ABT Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis School South Georgia State College Y N Douglas GA 4016 Abundant Life Christian School ELS Language Centers Dallas Y N Richardson TX 190950 ABX Air, Inc. Frederick KC Price III Christian Y N Los Angeles CA 389244 Acaciawood School Mid‐State Technical College ‐ MF Y Y Marshfield WI 31309 Academe of the Oaks Argosy University/Twin Cities Y N Eagan MN 7169 Academia Language School Kaplan University Y Y Lincoln NE 7068 Academic High School Ogden‐Hinckley Airport Y Y Ogden UT 553646 Academic High School Ogeechee Technical College Y Y Statesboro GA 3367 Academy at Charlemont, Inc. -

Approaches to Student Leadership

Volume 40 May 2008 www.agsa.org.au in alliance in this issue Approaches to Student Leadership Choosing a Career at MLC, Melbourne The Alliance of Girls’ Schools GPO Box 55 From the President... Hobart Tas 7001 Australia Executive Officer Susan Just Jan Butler T: +61 3 6234 2114 F: +61 3 6234 2115 M: 0417 962 466 E: [email protected] I would like to extend an invitation to staff at member attributes of leadership. While the percentage of President schools to attend the annual Alliance of Girls’ Schools women in significant leadership roles remains low in Susan Just Conference to be held in Canberra from 20 June 2008. Australian society, it is imperative that Girls’ Schools Canberra Girls’ Our keynote speakers will challenge our thinking and provide opportunities for young women to learn and Grammar School, ACT we have included additional workshop opportunities demonstrate leadership. Executive so that we can share and communicate with our Within this edition of in Alliance, you will learn about Beth Blackwood colleagues. Transport to and from the conference the importance of leadership density in schools and Presbyterian Ladies’ venue has been arranged in order to maximize your the models that schools use to provide guidance to College, WA time at the conference and allow you time to enjoy the students as they learn to lead. It is only through such Kitty Guerin crisp Canberra winter. Our Lady of Mercy programs that our students will become confident and College, NSW A letter of congratulations has been sent on behalf capable leaders. Our students will have an opportunity of the Alliance of Girls’ Schools to Quentin Bryce. -

International Education at Lourdes Hill College Student Handbook 2019

International Education at Lourdes Hill College Student Handbook 2019 Lourdes Hill College International Education CRICOS No. 00503k Revision: 02 Dated 29/04/2019 Page 1 International Student Handbook Lourdes Hill College Lourdes Hill College International Education CRICOS No. 00503k Revision: 02 Dated 29/04/2019 Page 2 Contact Information: Lourdes Hill College 86 Hawthorne Rd Hawthorne Queensland 4171 Australia www.lhc.qld.edu.au General enquiries: Ph: +61 7 3399 8888 Enrolment: Ph: +61 7 3399 0498 Mrs Colette Duval Fax: +61 7 3899 1007 [email protected] Accounts enquiries: Ph: +61 7 3399 0412 Ms Nicole Conway International Education: Ph: +61 7 3399 0404 Mr Terry Niebling [email protected] Director of International Education: Ph: +61 7 3399 0506 Mrs Jane Winter [email protected] Lourdes Hill College International Education CRICOS No. 00503k Revision: 02 Dated 29/04/2019 Page 3 Table of Contents A Message from the Principal................................................................................... 06 Welcome to Australia............................................................... ................................. 07 Brisbane.......................................................................................................................................................................... 10 Important Information and Local Emergency Contacts........................................................ 11 Pre-arrival......................................................................................................................... -

Answers to Estimates Questions on Notice

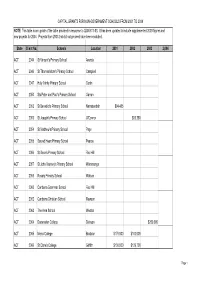

CAPITAL GRANTS FOR NON-GOVERNMENT SCHOOLS FROM 2001 TO 2004 NOTE: This table is an update of the table provided in response to QON 617-03. It has been updated to include supplemented 2003 figures and new projects for 2004. Projects from 2003 that did not proceed have been excluded. State Client No. Schools Location 2001 2002 2003 2,004 ACT 2044 St Vincent's Primary School Aranda ACT 2046 St Thomas More's Primary School Campbell ACT 2047 Holy Trinity Primary School Curtin ACT 2050 Sts Peter and Paul's Primary School Garran ACT 2052 St Benedict's Primary School Narrabundah $94,485 ACT 2053 St Joseph's Primary School O'Connor $93,280 ACT 2054 St Matthew's Primary School Page ACT 2055 Sacred Heart Primary School Pearce ACT 2056 St Bede's Primary School Red Hill ACT 2057 St John Vianney's Primary School Waramanga ACT 2058 Rosary Primary School Watson ACT 2060 Canberra Grammar School Red Hill ACT 2062 Canberra Christian School Mawson ACT 2063 The Ame School Weston ACT 2064 Daramalan College Dickson $250,000 ACT 2065 Merici College Braddon $176,000 $100,000 ACT 2066 St Clare's College Griffith $130,000 $129,700 Page 1 CAPITAL GRANTS FOR NON-GOVERNMENT SCHOOLS FROM 2001 TO 2004 State Client No. Schools Location 2001 2002 2003 2,004 ACT 2067 Marist College Canberra Pearce ACT 2068 St Edmund's College Griffith ACT 2900 St Thomas Aquinas Primary School Charnwood $105,000 ACT 2902 St Monica's Primary School Evatt ACT 2903 St Francis Xavier College Florey $254,588 $200,000 ACT 2904 St Thomas the Apostle Primary School Kambah ACT 2905 St Anthony's -

Hor Only.Point Score 2019

Aggregate Results - Head of the River 2019 Overall Place Total School 1st 2nd 3rd 4th 5th 6th 7th 8th 9th 10th 1 830 St Hilda's School 410 261 0 63 90 0 4 0 2 0 2 758 St Margaret's Anglican Girls School 280 198 88 70 30 50 0 30 12 0 3 705 All Hallows 100 144 224 140 6 30 60 0 0 1 4 581 Stuartholme School 10 252 80 84 120 35 0 0 0 0 5 576 Brisbane Girls Grammar School 50 0 136 133 144 110 0 3 0 0 6 498 Somerville House 50 0 160 105 48 70 60 0 0 5 7 289 Lourdes Hill College 50 0 0 14 60 70 44 36 10 5 8 222 Brisbane State High School 10 0 40 0 0 0 64 63 40 5 9 213 St Peters Lutheran College 0 9 48 7 0 25 24 60 40 0 10 98 St Aidan's Anglican Girls School 10 9 0 0 0 0 20 15 14 30 Percentage Cup Results - and Place Count Overall Place Total School 1st 2nd 3rd 4th 5th 6th 7th 8th 9th 10th 1 1.45 St Hilda's School 9 5 0 1 3 0 1 0 1 0 2 1.35 St Margaret's Anglican Girls School 4 6 3 2 1 2 0 2 2 0 3 1.02 Stuartholme School 1 4 2 4 4 3 0 0 0 0 4 0.75 Somerville House 1 0 4 3 4 2 3 0 0 1 5 0.6 All Hallows 2 4 4 4 1 2 3 0 0 1 6 0.51 Brisbane Girls Grammar School 1 0 5 3 4 6 0 1 0 0 7 0.29 Lourdes Hill College 1 0 0 2 2 2 3 4 1 1 8 0.28 St Peters Lutheran College 0 1 2 1 0 1 2 4 4 0 9 0.23 St Aidan's Anglican Girls School 1 1 0 0 0 0 1 1 3 6 10 0.17 Brisbane State High School 1 0 1 0 0 0 4 5 4 1 Summary of Year 8 Points Calculations Overall Place Total School 1st 2nd 3rd 4th 5th 6th 7th 8th 9th 10th 1 195 St Hilda's School 150 45 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 2 168 St Margaret's Anglican Girls School 0 135 8 0 0 25 0 0 0 0 3 141 Somerville House 50 0 80 0 6 0 0 0 -

Albion Park Adams, Ashlyn 15 1 Westfields S Adeniran, Shola

Sydney Olympic Park 2 - Site License Hy-Tek's MEET MANAGER 5:25 PM 24/09/2019 Page 1 2019 NSW All Schools Championships - 26/09/2019 to 29/09/2019 Track and Field Championships SOPAC, Homebush Performance List Event 226 Girls 100 Meter Sprint 15 years Prelims Comp# Name Age Team Seed Time 1 Adams, Ashlyn 15 Albion Park 2 Adeniran, Shola 15 Westfields S 3 Adra, Amani 15 East Hills G 4 Ahmad, Salam 15 Meridan Stra 5 Bannister, Emily 15 Pymble Ladie 6 Beaven, Jade 15 St Josephs E 7 Bowley, Sophie 15 Temora High 8 Burgers-Rebec, Hunter 15 Emmaus Catho 9 Clancy, Charlotte 15 Roseville College 10 Fichardt, Georgia 15 Abbotsleigh 11 Flanagan, Lucy 15 Bethany Coll 12 Garnett, Ella 15 Plc Sydney Croydon 13 Gill, Imogen 15 St Vincents 14 Hamilton, Erin 15 Central Coas 15 Jenkins, Alyssa 15 Coffs Harbour High 16 Lammers, Zara 15 Kirrawee High 17 Latimer, Sophie 14 Elderslie High 18 Lee, Regina 15 Meridan Stra 19 Lee, Regina 15 Trinity Grammar 20 Martin, Alannah 15 St Agnes Hig 21 McAndrew, Adria 15 Riverside Gi 22 Moore, Kailee 15 Holy Spirit 23 Parkes, Giorgi 15 St Catherine 24 Percival, Lauren 15 Ulladulla High 25 Plummer, Amalia 15 Magdalene Ca 26 Rogers, Sabina 15 Bulli High Sydney Olympic Park 2 - Site License Hy-Tek's MEET MANAGER 5:25 PM 24/09/2019 Page 2 2019 NSW All Schools Championships - 26/09/2019 to 29/09/2019 Track and Field Championships SOPAC, Homebush Performance List Event 226 ... (Girls 100 Meter Sprint 15 years Prelims) Comp# Name Age Team Seed Time 27 Stevens, Georgia 15 Danebank €“ 28 Tozer, Eleanor 15 Smiths Hill High 29 Wadley, -

Modern Slavery Statement 2019-2020

MODERN SLAVERY STATEMENT 2019-2020 1 | P a g e MODERN SLAVERY STATEMENT 2019–20 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This statement sets out the actions to address Kildare Education Ministries’ reporting obligations under the Modern Slavery Act 2018 (the Act) as an entity that has a consolidated revenue equal to or slightly greater than $100 million. Kildare Education Ministries (KEM) has zero tolerance to modern slavery and human trafficking within our operations and its business and supply chains. We are committed to being an ethical employer. We are committed to promoting responsible business and upholding high ethical standards to ensure the protection of human rights of all individuals in our supply chains. We have identified some of the major risks of modern slavery in our operations and supply chains and are committed to implementing effective controls to ensure mitigation or elimination of those risks. SECTION ONE: COVERED ENTITIES Section 16(1)(a) of the Modern Slavery Act 2018 requires modern slavery statements to identify the reporting entity or entities covered by the statement. This section of the statement addresses this criterion by providing an overview of which schools are covered by the Statement. Kildare Education Ministries Limited is a public company limited by guarantee, established in 2014 operating under ABN 34169198421. Kildare Education Ministries is the governing Board for the following secondary Colleges employing over 600 full time equivalent staff: Clonard College Herne Hill, VIC Kilbreda College Mentone, VIC Kildare College Holden Hill, SA Killester College Springvale, VIC Marian College Ararat, VIC Marian College Sunshine West, VIC St Joseph's College Echuca, VIC 2 | P a g e This statement covers the activities of Kildare Education Ministries and its controlled entities listed above.