Disaster Complexity and the Santiago De Compostela Train Derailment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Follow the Camino – the Way of St

Follow the Camino – The Way of St. James Day 1 Arrive Lisbon Welcome to Portugal! Upon clearing customs, transfer as a group to your hotel. Take some time to rest and relax before this evening’s included welcome dinner at the hotel. (D) Day 2 Lisbon – Santarem - Fatima Sightseeing with a Local Guide features visits to JERONIMOS MONASTERY and the CHURCH OF ST. ANTHONY. Afterwards, depart for Fatima and while en route, visit the CHURCH OF THE HOLY MIRACLE in Santarém, site of a famous Eucharistic Miracle. Then, visit OUR LADY OF FATIMA SHRINE with the tombs of the visionaries, and the CHAPEL OF THE APPARITIONS, where the Virgin Mary appeared to three children in 1917. Enjoy dinner at your hotel and later, perhaps join this evening’s rosary and candlelight procession at the Our Lady of Fatima Shrine, or attend Mass, held every day at 6 pm at the basilica. (B,D) Day 3 Fatima – Braga - Sarria Journey north this morning and stop in Braga, one of the oldest Christian cities in the world and nicknamed the “Portuguese Rome.” Enjoy a unique experience as you ride the water funicular, built in 1882, to reach the Bom Jesus do Monte (Good Jesus of the Mount) sanctuary. See the unique zigzag stairway that is dedicated to the five senses—sight, smell, hearing, touch, and taste—and the three theological virtues—faith, hope, and charity. Later, cross into Spain and head for Sarria where tomorrow you will start your walking pilgrimage. Tonight, dinner is included at a local restaurant. (B) Day 4 Sarria – Portomarin (Walking Day 14.3 Miles) After breakfast we will go to the PILGRIM OFFICE to request our PILGRIM PASSPORT and we will start our walking pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela. -

High Speed Rail in Spain - a Statement from a Foreign Expert

25 número 6 - junio - 2018. Pág 477 - 509 High Speed Rail in Spain - a statement from a foreign expert Andersen, Sven Senior Consultant for High Speed Rail1 Abstract In Spain all high speed trains run over tracks in a special built high speed network. No disturbing influences have to be taken into account for daily operation process. This is a great advantage. Spain shares this advantage with the high speed rail networks in Japan, Taiwan and China. Running trains on parallel train paths and at least from case to case in 3 minutes headway to each other is a basic condition to reach a high use to capacity. But Spain is running trains with different speeds on its high speed lines. Another condition for a high cost-benefitratio is a strict regular service with at least one service per hour. RENFE however is running the AVE trains in a rather irregular timetable. Some examples will be presented to demonstrate this fact. The author gives some comparisons of travel times in Spain, Japan and China. The routing data of the AVE line Madrid - Sevilla is compared with those of the Shinkansen Shin Osaka - Hakata. Based on this comparison the author proposes an upgrading of the AVE-Line Madrid - Sevilla for 300 km/h. A strict regular service for all AVE lines can be developed on the basis of a new travel time Madrid - Sevilla with 118 min together with a 142 min nonstop travel time Barcelona - Madrid. The cost-benefit analysis shows several results, above all nearly 100% more train kilometres as well as saving of running days from EMU’s and track change constructions. -

Memoria Y Anejos Documento 1 Estudio Informativo De La Nueva Red Ferroviaria Del País Vasco

MEMORIA Y ANEJOS DOCUMENTO 1 ESTUDIO INFORMATIVO DE LA NUEVA RED FERROVIARIA DEL PAÍS VASCO. CORREDOR DE ACCESO Y ESTACIÓN DE BILBAO-ABANDO. FASE B MEMORIA ESTUDIO INFORMATIVO DE LA NUEVA RED FERROVIARIA DEL PAÍS VASCO. CORREDOR DE ACCESO Y ESTACIÓN DE BILBAO-ABANDO. FASE B MEMORIA ÍNDICE 1. Introducción y objeto .............................................................. 1 7.2. Alternativa 1. Acceso Este ............................................................... 30 7.3. Alternativa 2. Acceso Oeste ............................................................. 31 2. Antecedentes ........................................................................... 2 7.4. Nueva Estación de Abando ............................................................. 32 2.1. Antecedentes administrativos ............................................................ 2 7.4.1. Alta Velocidad (Nivel -2) ................................................................. 32 2.2. Antecedentes técnicos ....................................................................... 3 7.4.2. Cercanías/Ancho Métrico (Nivel -1) ................................................ 32 3. Características fundamentales de la actuación .................... 4 7.4.3. Planta Técnica (Nivel -1,5) ............................................................. 33 3.1. Justificación de la solución ................................................................. 4 7.5. Reubicaciones de la Base de mantenimiento .................................. 33 3.2. Cumplimiento del Real Decreto 1434/2010 -

Marian Shrines of France, Spain, and Portugal

Tekton Ministries “Serving God’s people on their journey of faith” Pilgrimage to the Marian Shrines of France, Spain, and Portugal with Fr. John McCaslin and Fr. Jim Farrell April 4th - 16th, 2016 e Pilgrimage Itinerary e Fatima Santiago de Compostela e Day 1 - April 4: Depart U.S.A. Your pilgrimage begins today as you depart on your e Day 4 - April 7: Fatima / Santiago de Compostela flight to Portugal. Depart Fatima this morning and drive north to Porto where we will visit the soaring Cathedral and admire e Day 2 - April 5: Arrive Lisbon / Fatima the richly decorated Church of Sao Francisco. Then After a morning arrival in Lisbon, you will meet your proceed to Braga which contains over 300 churches knowledgeable local escort, who in addition to the and is the religious center of Portugal. Our sightseeing priests accompanying your pilgrimage, will be with here will include visits to Braga’s Sé Cathedral which you throughout your stay. Drive north to Fatima, one is the oldest in Portugal and the Bom Jesus do Monte of the world’s most important Marian Shrines and an which is an important pilgrimage shrine. Then important center for pilgrimages. Time permitting we continue on to Santiago de Compostela. Tradition will make a stop in Santarem for Mass at the Church tells us that St. James the Apostle journeyed to Spain of St. Stephen, famous for its venerated relic, “the in 40 A.D. to spread the Gospel as far as possible. He Bleeding Host” en route from Lisbon to Fatima. died a martyr’s death after returning to Jerusalem and his remains were eventually returned to Spain and e Day 3 - April 6: Fatima buried in this city. -

Promoting and Financing Cultural Tourism in Europe Through European Capitals of Culture: a Case Study of Košice, European Capital of Culture 2013

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Šebová, Miriam; Peter Džupka, Oto Hudec; Urbancíková, Nataša Article Promoting and Financing Cultural Tourism in Europe through European Capitals of Culture: A Case Study of Košice, European Capital of Culture 2013 Amfiteatru Economic Journal Provided in Cooperation with: The Bucharest University of Economic Studies Suggested Citation: Šebová, Miriam; Peter Džupka, Oto Hudec; Urbancíková, Nataša (2014) : Promoting and Financing Cultural Tourism in Europe through European Capitals of Culture: A Case Study of Košice, European Capital of Culture 2013, Amfiteatru Economic Journal, ISSN 2247-9104, The Bucharest University of Economic Studies, Bucharest, Vol. 16, Iss. 36, pp. 655-671 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/168849 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. -

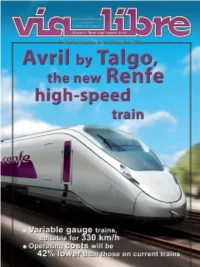

Avril by Talgo. the New Renfe High-Speed Train

Report - New high-speed train Avril by Talgo: Renfe’s new high-speed, variable gauge train On 28 November the Minister of Pub- Renfe Viajeros has awarded Talgo the tender for the sup- lic Works, Íñigo de la Serna, officially -an ply and maintenance over 30 years of fifteen high-speed trains at a cost of €22.5 million for each composition and nounced the award of a tender for the Ra maintenance cost of €2.49 per kilometre travelled. supply of fifteen new high-speed trains to This involves a total amount of €786.47 million, which represents a 28% reduction on the tender price Patentes Talgo for an overall price, includ- and includes entire lifecycle, with secondary mainte- nance activities being reserved for Renfe Integria work- ing maintenance for thirty years, of €786.5 shops. The trains will make it possible to cope with grow- million. ing demand for high-speed services, which has increased by 60% since 2013, as well as the new lines currently under construction that will expand the network in the coming and Asfa Digital signalling systems, with ten of them years and also the process of Passenger service liberaliza- having the French TVM signalling system. The trains will tion that will entail new demands for operators from 2020. be able to run at a maximum speed of 330 km/h. The new Avril (expected to be classified as Renfe The trains Class 106 or Renfe Class 122) will be interoperable, light- weight units - the lightest on the market with 30% less The new Avril trains will be twelve car units, three mass than a standard train - and 25% more energy-effi- of them being business class, eight tourist class cars and cient than the previous high-speed series. -

Learn Spanish in Unesco World Heritage Cities of Spain

LEARN SPANISH IN UNESCO WORLD HERITAGE CITIES OF SPAIN Alcalá de Henares Salamanca Ávila San Cristóbal de La Laguna Baeza Santiago de Compostela Cáceres Segovia Córdoba Tarragona Cuenca Toledo Ibiza/Eivissa Úbeda www.ciudadespatrimonio.org Mérida www.spainheritagecities.com NIO M NIO M O UN O UN IM D IM D R R T IA T IA A L A L • P • P • • W W L L O O A A I I R R D D L L D D N N H O H O E M E M R R I E I E TA IN TA IN G O G O E • PATRIM E • PATRIM Organización Patrimonio Mundial Organización Patrimonio Mundial de las Naciones Unidas en España de las Naciones Unidas en España para la Educación, para la Educación, la Ciencia y la Cultura la Ciencia y la Cultura Santiago de Compostela Tarragona Salamanca Segovia Alcalá de Henares Ávila Cáceres Cuenca Toledo Mérida Ibiza/Eivissa Úbeda Córdoba Baeza San Cristóbal de La Laguna 2 3 Alcalá de Henares Ávila Baeza Cáceres Córdoba Cuenca Ibiza/Eivissa Mérida Salamanca San Cristóbal de La Laguna Santiago de Compostela Segovia Tarragona Toledo Úbeda CITIES reinvented Spain is privileged to be among the countries with the great number of sites on UNESCO’s World Heritage List. The Spanish Group of World Heritage Cities began to combine their efforts in 1993 to create a nonprofit Association, with the specific objective of working together to defend the historical and cultural heritage of these cities: Alcalá de Henares, Ávila, Baeza, Cáceres, Córdoba, Cuenca, Ibiza/Eivissa, Mérida, Salamanca, San Cristóbal de La Laguna, Santiago de Compostela, Segovia, Tarragona, Toledo and Úbeda. -

The North Way

PORTADAS en INGLES.qxp:30X21 26/08/09 12:51 Página 6 The North Way The Pilgrims’ Ways to Santiago in Galicia NORTE EN INGLES 2009•.qxd:Maquetación 1 25/08/09 16:19 Página 2 NORTE EN INGLES 2009•.qxd:Maquetación 1 25/08/09 16:20 Página 3 The North Way The origins of the pilgrimage way to Santiago which runs along the northern coasts of Galicia and Asturias date back to the period immediately following the discovery of the tomb of the Apostle Saint James the Greater around 820. The routes from the old Kingdom of Asturias were the first to take the pilgrims to Santiago. The coastal route was as busy as the other, older pilgrims’ ways long before the Spanish monarchs proclaimed the French Way to be the ideal route, and provided a link for the Christian kingdoms in the North of the Iberian Peninsula. This endorsement of the French Way did not, however, bring about the decline of the Asturian and Galician pilgrimage routes, as the stretch of the route from León to Oviedo enjoyed even greater popularity from the late 11th century onwards. The Northern Route is not a local coastal road for the sole use of the Asturians living along the Alfonso II the Chaste. shoreline. This medieval route gave rise to an Liber Testamenctorum (s. XII). internationally renowned current, directing Oviedo Cathedral archives pilgrims towards the sanctuaries of Oviedo and Santiago de Compostela, perhaps not as well- travelled as the the French Way, but certainly bustling with activity until the 18th century. -

PDF: Horario De ALVIA, Paradas Y Mapa

Horario y mapa de la línea ALVIA de tren ALVIA Ourense - A Coruña (Santiago de Compostela) - Ver En Modo Sitio Web Lugo - Pontevedra (Vigo) - Barcelona - Madrid La línea ALVIA de tren (Ourense - A Coruña (Santiago de Compostela) - Lugo - Pontevedra (Vigo) - Barcelona - Madrid) tiene 8 rutas. Sus horas de operación los días laborables regulares son: (1) a A Coruña: 21:20 (2) a A Coruña (Ferrol): 13:47 - 19:46 (3) a Barcelona: 9:16 (4) a Lugo: 17:57 (5) a Madrid: 6:28 - 17:49 (6) a Madrid - Alicante: 10:27 (7) a Pontevedra (Vigo): 12:00 - 21:07 (8) a Santiago De Compostela: 23:25 Usa la aplicación Moovit para encontrar la parada de la línea ALVIA de tren más cercana y descubre cuándo llega la próxima línea ALVIA de tren Sentido: A Coruña Horario de la línea ALVIA de tren 24 paradas A Coruña Horario de ruta: VER HORARIO DE LA LÍNEA lunes 21:20 martes 21:20 Barcelona-Sants 1-7 Plaça dels Països Catalans, Barcelona miércoles Sin servicio Camp De Tarragona jueves 21:20 Lleida Pirineus viernes Sin servicio sábado 21:20 Zaragoza-Delicias domingo Sin servicio Tudela De Navarra Plaza de la estación, Tudela Castejon De Ebro Información de la línea ALVIA de tren Tafalla Dirección: A Coruña Avenida Sangüesa, Tafalla Paradas: 24 Duración del viaje: 780 min Pamplona-Iruña Resumen de la línea: Barcelona-Sants, Camp De Plaza de la Estación, Pamplona/Iruña Tarragona, Lleida Pirineus, Zaragoza-Delicias, Tudela De Navarra, Castejon De Ebro, Tafalla, Pamplona- Vitoria-Gasteiz Iruña, Vitoria-Gasteiz, Miranda De Ebro, Burgos-Rosa 46 Eduardo Dato kalea, Vitoria-Gasteiz -

Cambio Automático De Ancho De Vía De Los Trenes En España

CAMBIO AUTOMÁTICO DE ANCHO DE VÍA DE LOS TRENES EN ESPAÑA Alberto García Álvarez DOCUMENTOS DE EXPLOTACIÓN ECONÓMICA Y TÉCNICA DEL FERROCARRIL Septiembre 2010 COLECCIÓN MONOGRAFÍAS VÍA LIBRE nº 2 Cambio automático de ancho de vía de los trenes en España Alberto García Álvarez COLECCIÓN MONOGRAFÍAS VÍA LIBRE nº 2 Cambio automático de ancho de vía de los trenes España Alberto García Álvarez Monografía basada en los artículos: “Cambiadores de ancho, trenes de ancho variable y tercer carril: Nuevas soluciones a un viejo problema”, en la Revista Anales de Mecánica y Electricidad, enero-febrero de 2007; “Los de Roda y Antequera incorporan todas las novedades: Los cambiadores de ancho, nueva solución a un viejo problema”, en Vía Libre, enero de 2007; y “Cambiadores de la línea de Madrid a Valladolid”, en Vía Libre, diciembre de 2007. Estos textos han sido refundidos, ampliados y actualizados por el autor en 2009. Palabras clave: Ferrocarril, interoperabilidad, cambio de ancho, alta velocidad © Autor: Alberto García Álvarez © De esta edición: Fundación de los Ferrocarriles Españoles Mapas e ilustraciones: Miguel Jimenez Vega y Luis Eduardo Mesa Santos 4º edición, septiembre de 2010 ISBN:978-84-89649-55-2 Dto. Legal: M-26703-2009 ÍNDICE ÍNDICE .................................................................................................. 3 INTRODUCCIÓN ....................................................................................... 5 El problema y las soluciones de la diferente anchura de vía .....................................5 -

Guía De Trenes Y Estaciones Accesibles

APARTADO A ESTACIONES Y PRODUCTOS DE AVE–LARGA DISTANCIA Y MEDIA DISTANCIA CON SERVICIO DE ASISTENCIA Ver notas aclaratorias de productos y estaciones al final del apartado. ACCESIBILIDAD DE LA ESTACIÓN PUNTO DE ESTACIÓN PRODUCTOS FERROVIARIOS ENCUENTRO PLAZA ASEOS VESTÍBULO Y APARCAMIENTO ENTRE ANDENES SILLA DE RUEDAS DE SILLA ZONA COMERCIAL ZONA COMERCIAL Arco (b), Talgo (a), Trenhotel (e) y A Coruña Atención al Cliente Media Distancia (c) • • • • • Alaris, Alvia, Euromed, Alacant/Alicante Atención al Cliente Talgo (a)(b) y Media Distancia (c) • • • • • Ave, Alaris, Altaria (a), Alvia, Albacete Los Llanos Arco (b), Talgo (a) y Atención al Cliente • • • • • Media Distancia (c) Alaris, Altaria (a), Alcázar de San Juan Arco (b), Talgo (a) y Venta de Billetes • • • • • Media Distancia (c) Altaria (a) (d) y Algeciras Venta de Billetes Media Distancia (c) • • • • • Alvia, Talgo (a) y Almansa Venta de Billetes Media Distancia (c) • • • • Arco (b), Talgo (a) y Almería Intermodal Atención al Cliente Media Distancia (c) • • • • Altaria (a)(d), Ave y Antequera Sta. Ana Atención al Cliente Avant • • • • • Avila Media Distancia (c) Venta de Billetes • • • • Badajoz Arco (b) y Media Distancia (c) Venta de Billetes • • • • • Altaria (a) , Talgo (a)(b) y Balsicas - Mar Menor Venta de Billetes Media Distancia (c) • • • • Barcelona França Media Distancia (c) Atención al Cliente • • • • • Alaris, Alvia, Arco (b), Ave, Enlace Internacional, Barcelona - Sants Euromed, Talgo (a)(b), Atención al Cliente • • • • • Trenhotel (e)(f), Avant y Media Distancia -

La Ministra De Fomento Presenta El Nuevo Tren Alvia Híbrido De Alta Velocidad De Renfe Que Unirá Galicia Y Madrid

En servicio a partir del 17 de junio La ministra de Fomento presenta el nuevo tren Alvia híbrido de alta velocidad de Renfe que unirá Galicia y Madrid • El tiempo de viaje con la capital de España se reduce más de 30 minutos y con Alicante se verá recortado en más de 2 horas • Los precios de los billetes serán los mismos que los del actual servicio • En la fabricación de los trenes, Serie 730, en la que han rensa participado Talgo y Bombardier, se ha invertido un total de 78 p millones de euros Santiago, 9 de junio de 2012. La ministra de Fomento, Ana Pastor, ha presentado hoy los nuevos trenes Alvia “híbridos-duales” de Renfe de la serie 730 entre Galicia y Madrid (los fines de semana continúan a Alicante). Los nuevos trenes híbridos-duales S-730, que sustituirán a los Talgo actuales, permitirán extender los beneficios de la alta velocidad a Nota de tramos de vía no electrificados, lo que supondrá una reducción de los tiempos de viaje de más de 30 minutos entre las dos comunidades. Reducción de tiempos Los trenes Alvia entre Madrid y Galicia recortarán significativamente su tiempo de viaje, lo que les hará más competitivos con la carretera: • Madrid-Zamora: 2 horas (actual 2.24) • Madrid-Ourense: 4 horas y 48 minutos (actual 5.20) • Madrid-Santiago: 5 horas y 36 minutos (actual 6.07) • Madrid-A Coruña: 6 horas y 9 minutos (actual 6.40) • Madrid-Vigo: 6 horas y 22 minutos (actual: 7.15) Esta información puede ser utilizada en su integridad o en parte sin necesidad de citar fuentes.