Santiago De Compostela

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 One of Many Interesting Demo-Geographic Processes In

TOPIC/SESSION 401 (REGIONAL AND URBAN ISSUES) GUIDELINES OF SECOND HOMES LOCATION IN SPANISH URBAN POPULATION: SOCIAL DEMOGRAPHIC AND TERRITORIAL ANALYSIS. JUAN ANTONIO MÓDENES CABRIZO Department of Geography, Autonomous University of Barcelona and Demographic Studies Centre JULIAN LÓPEZ COLÁS Demographic Studies Centre (Barcelona, Spain) BRENDA YÉPEZ MARTÍNEZ Demographic Studies Centre (Barcelona, Spain) One of many interesting demo-geographic processes in Spain become the expansion of the second homes and the consequent transformation of wide zones close to the big cities, coasts, and interior zones which turned to be increasingly attractive. Most second homes are purchased for personal reasons. In some cases owners use their second home as a sort of refuge to temporarily escape their urban environment. Part of this demand, specially in the Mediterranean coast occurs because the international request attracted by the climate, the differential level in life standards, and the present transport facility. Nonetheless, the internal demand is very important and continues to grow. If in 1991, 12% of the Spanish resident homes possessed a secondary household, in 2001 it was already increasing to 15%. Almost one of each seven homes is immersed in multiple residence strategy. Diverse studies have demonstrated the interactions between housing characteristics, those related to the habitual residences and the possession of second homes. Generally they have concluded that the main explanatory factors are, on one hand, a dense and compact habitat, and by other hand, the socio-demographics and socioeconomic status of secondary residence users. Nevertheless, the guideline of location of this type of housing and its interaction with homes characteristics seems to be a less treated subject. -

The Differences of Slovenian and Italian Daily Practices Experienced in the First Wave of Covid-19 Pandemic

The Differences of Slovenian and Italian Daily Practices Experienced in the First Wave of Covid-19 Pandemic Saša Pišot ( [email protected] ) Science and Research Centre Koper Boštjan Šimunič Science and Research Centre Koper Ambra Gentile Università degli Studi di Palermo Antonino Bianco Università degli Studi di Palermo Gianluca Lo Coco Università degli Studi di Palermo Rado Pišot Science and Research Centre Koper Patrik Dird Faculty of Sport and Physical Education, University of Novi Sad, Serbia Ivana Milovanović Faculty of Sport and Physical Education, University of Novi Sad, Serbia Research Article Keywords: Physical activity and inactivity behavior, dietary/eating habits, well-being, home connement, COVID-19 pandemic measures Posted Date: June 9th, 2021 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-537321/v1 License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Read Full License Page 1/18 Abstract Background: The COVID-19 pandemic situation with the lockdown of public life caused serious changes in people's everyday practices. The study evaluates the differences between Slovenia and Italy in health- related everyday practices induced by the restrictive measures during rst wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. Methods: The study examined changes through an online survey conducted in nine European countries from April 15-28, 2020. The survey included questions from a simple activity inventory questionnaire (SIMPAQ), the European Health Interview Survey, and some other questions. To compare changes between countries with low and high incidence of COVID-19 epidemic, we examine 956 valid responses from Italy (N=511; 50% males) and Slovenia (N=445; 26% males). -

Follow the Camino – the Way of St

Follow the Camino – The Way of St. James Day 1 Arrive Lisbon Welcome to Portugal! Upon clearing customs, transfer as a group to your hotel. Take some time to rest and relax before this evening’s included welcome dinner at the hotel. (D) Day 2 Lisbon – Santarem - Fatima Sightseeing with a Local Guide features visits to JERONIMOS MONASTERY and the CHURCH OF ST. ANTHONY. Afterwards, depart for Fatima and while en route, visit the CHURCH OF THE HOLY MIRACLE in Santarém, site of a famous Eucharistic Miracle. Then, visit OUR LADY OF FATIMA SHRINE with the tombs of the visionaries, and the CHAPEL OF THE APPARITIONS, where the Virgin Mary appeared to three children in 1917. Enjoy dinner at your hotel and later, perhaps join this evening’s rosary and candlelight procession at the Our Lady of Fatima Shrine, or attend Mass, held every day at 6 pm at the basilica. (B,D) Day 3 Fatima – Braga - Sarria Journey north this morning and stop in Braga, one of the oldest Christian cities in the world and nicknamed the “Portuguese Rome.” Enjoy a unique experience as you ride the water funicular, built in 1882, to reach the Bom Jesus do Monte (Good Jesus of the Mount) sanctuary. See the unique zigzag stairway that is dedicated to the five senses—sight, smell, hearing, touch, and taste—and the three theological virtues—faith, hope, and charity. Later, cross into Spain and head for Sarria where tomorrow you will start your walking pilgrimage. Tonight, dinner is included at a local restaurant. (B) Day 4 Sarria – Portomarin (Walking Day 14.3 Miles) After breakfast we will go to the PILGRIM OFFICE to request our PILGRIM PASSPORT and we will start our walking pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela. -

The Medieval Pilgrim Routes Through France and Spain to Santiago De Compostela Free Download

THE ROADS TO SANTIAGO: THE MEDIEVAL PILGRIM ROUTES THROUGH FRANCE AND SPAIN TO SANTIAGO DE COMPOSTELA FREE DOWNLOAD Derry Brabbs | 253 pages | 20 Jun 2013 | Frances Lincoln Publishers Ltd | 9780711234727 | English | London, United Kingdom The Pilgrimage Roads: Of the Route of Saint James Want to Read Currently Reading Read. In this way, Galicia can be reached The Roads to Santiago: The Medieval Pilgrim Routes Through France and Spain to Santiago de Compostela the province of Ourense. Sue rated it it was amazing Nov 25, The route has an imposing splendour of scenery, as well as countless historical and heritage resources… Learn more. Share One of the most popular events of the elaborate half-week of festivities is the swinging of the centuries-old, solid silver censer called the botafumeiro. The pilgrim's staff is a walking stick used by pilgrims on the way to the shrine of Santiago de Compostela in Spain. Some people set out on the Camino for spiritual reasons; many others find spiritual reasons along the Way as they meet other pilgrims, attend pilgrim masses in churches and monasteries and cathedrals, and see the large infrastructure of buildings provided for pilgrims over many centuries. This practice gradually led to the scallop shell becoming the badge of a pilgrim. Here only a few routes are named. People who want to have peace of mind will benefit from an organized tour or a self-guided tour while many will opt to plan the camino on their own. The city virtually explodes with activity for several days previous, culminating in a great spectacle in the plaza in front of the cathedral on the eve of the feast day. -

Cross-Board Territorial Co-Operation Challenges in Europe: Some Reflections from Galicia-Northern Portugal Experience

Cross-board Territorial Co-operation Challenges in Europe: some reflections from Galicia-Northern Portugal experience Luís Leite Ramos MP - Portugal, Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe International Conference CROSS-BORDER COOPERATION IN EUROPE 25 May 2018 | Dubrovnik, Croatia Spain and Portugal Border: one of the oldest in Europe. International Conference CROSS-BORDER COOPERATION IN EUROPE 25 May 2018 | Dubrovnik, Croatia Portugal and Spain, nine centuries of rivalry and mistrust The relations between 2 countries have often been difficult. They have been rivals at the see conquest as early as in the XIVth century and they have been enemies in many wars. Even when Spain and Portugal fought to keep their colonies around the globe, some co- operation existed between them. For nine centuries rivalry and mistrust defined the relations between Spain and Portugal. International Conference CROSS-BORDER COOPERATION IN EUROPE 25 May 2018 | Dubrovnik, Croatia … but a common history and future International Conference CROSS-BORDER COOPERATION IN EUROPE 25 May 2018 | Dubrovnik, Croatia Galicia and Northern Portugal CBC - legal framework Spain-Portugal Friendship and Co-operation Treaty - 27th November 1977 Council of Europe Madrid Outline Convention on Cross-Border Cooperation between Territorial Communities or Authorities, Council of Europe (21st May1980) Portugal and Spain ratified the Council of Europe Madrid Outline Convention – 1989 | 1990. Constitutive Agreement of the Galicia-Northern Portugal Working Community – 1991 Cross-Border -

Guia De Los Caminos Del Norte a Santiago

Los Caminos del Norte a Santiago Camino del Norte_Camino Primitivo_Camino del Interior Camino Baztanés _Camino Lebaniego - 2ª Edición: Agosto 2011 - Edita: Gobierno Vasco, Gobierno de Cantabria, Gobierno del Principado de Asturias, Xunta de Galicia, Gobierno de Navarra, Gobierno de La Rioja. - Coordinación: Gobierno Vasco - Diseño y realización: ACC Comunicación - Impresión: Orvy Impresión Gráfi ca, S.L. - Depósito Legal: SS-1034-2011 - Fotografías: Archivo de Patrimonio del Gobierno Vasco, © M. Arrazola. EJ-GV, Quintas Fotógrafos, Archivo ACC, Archivo de la Consejería de Cultura del Gobierno de Cantabria, D.G. Turismo y Patrimonio Cultural del Principado de Asturias, Infoasturias (Juanjo Arroyo, Marcos Morilla, Camilo Alonso, Arnaud Späni, Daniel Martín, Antonio Vázquez, M.A.S., Mara Herrero), Comarca de la Sidra (José Suárez), José Salgado. Índice 16 ... CAMINO DEL NORTE 96 ... CAMINO PRIMITIVO 18 ... Euskadi 98 ... Asturias ...1 Irun - Hondarribia > Donostia-San Sebastián 98... Enlace 1. Sebrayu > Vega (Sariego) 06 ... Los Caminos del Norte, 18 100... Enlace 2. Vega (Sariego) > Oviedo una oportunidad para el encuentro 20.........Donostia-San Sebastián 22...2 Donostia-San Sebastián > Zarautz 102......Oviedo 104...1 Oviedo > San Juan de Villapañada 08 ... Los Caminos a Santiago: mil años 24...3 Zarautz > Deba 106...2 San Juan de Villapañada > Salas de Historia para millones de historias 26...4 Deba > Markina-Xemein 28...5 Markina-Xemein > Gernika-Lumo 108...3 Salas > Tineo 110...4 Tineo > Borres 12 ... Consejos prácticos 30...6 Gernika-Lumo > Bilbao 32.........Bilbao 112...5 Borres > Berducedo 34...7 Bilbao > Portugalete 114...6 Berducedo > Grandas de Salime 36...8 Portugalete > Kobaron 116...7 Grandas de Salime > Alto de El Acebo 118...Galicia 38 .. -

The Rev. Dr. Robert M. Roegner

RLCMussiaS WORLD MISSIONandTOUR the Baltics May 22 - June 4, 2007 Hosted by The Rev. Dr. Robert & Kristi Roegner The Rev. Dr. William & Carol Diekelman The Rev. Brent & Jennie Smith 3 o c s o M , n i l m e r K e h t n a e r a u - S e R Dear Friends o. LCMS World Mission, One never knoIs Ihere and Ihen od Iill open a door for the ood NeIs of Jesus. /ith the fall of the Iron Curtain, od opened a door of huge opportunity in Russia and Eastern Europe. ,he collapse of European Communism also brought us in touch--and in partnership--Iith felloI Lutherans Iho by od's grace had remained steadfast in the faith through decades of persecuMOSCOWtion. ,oday, LCMS /orld Mission and its partners are AblaLe! as Ie seek to share the ospel Iith 100 million unreached or uncommitted people IorldIide by 2017, the 500th anniversary of the Reformation. I invite you to join me and my Iife, $risti, and LCMS First .ice President Bill Diekelman and his Iife, Carol, on a very special AblaLe! tour of Russia, Latvia, and Lithuania. Joining and guiding us Iill be LCMS /orld Mission's Eurasia regional director, Rev. Brent Smith, and his STIife, Jennie. PETERSBURG Not only Iill Ie visit some of the Iorld's most famous, historic, and grand sites, but you Iill have the rare opportunity to meet Iith LCMS missionaries and felloI Lutherans from our partner churches for a first-hand look at hoI od is using them to proclaim the ospel in a region once closed to us. -

Landscape in Galicia and Asturias

Landscape in Galicia and Asturias Francisco José Flores Díaz [email protected] Where are the regions? ·Area:40.178 Km² ·Population:3,72 millions ·Population density:92,63 person/Km² ·The most important rivers are “Miño”. “Eo” and “Sil” ·The most part of the population lives near the coast, specially in three big cities. Climate Characteristics: -Strong changes between seasons -High humidity -High precipitation -Drought in summer -Minor temperature variations on the coast than interior Soil Soils are generally: -shallow -with a sandy or loamy texture, - acidic and with abundant organic matter, which gives the upper layer its typical dark color -Without lack of necessary elements for the plants ● -Granitic majority Landscape of the area We can distinguish three types of landscapes: -Mountainous -Inrerior -Coastal Great plant and animal biodiversity Some endemic Protected spaces Areas with special ecological characteristics restricted for different economic and productive uses. Around 15% of territory Issues of the area ·Soil salinization ·Erosion of surface ·Fires ·Contamination of the soil and water ·Destruction of river banks ·Compactation of the soil Soil salinization It is not the main problem in the region, but it appears in areas where rainfall is less abundant and fertilization is excessive It affects: · Chemical properties of soil · Microorganisms ·Plant growth Erosion surface Caused: · Loss of vegetation cover Excessive cattle · Fires · Torrential rains Fires Contamination of the soil and water There is a very large thermal power -

Catedral Camino De Santiago

joyas del prerrománico, San Miguel de Lillo y Santa María del Naranco. del María Santa y Lillo de Miguel San prerrománico, del joyas Fuente de Foncalada de Fuente Iglesia de Lloriana de Iglesia Llampaxuga señalización del camino del señalización en el primer peregrino primer el en al Oeste y, en su frente, la ladera ya visible del monte Naranco con las dos dos las con Naranco monte del visible ya ladera la frente, su en y, Oeste al Capilla del Carmen del Capilla Símbolo urbano de urbano Símbolo del Apóstol Santiago convirtiéndose convirtiéndose Santiago Apóstol del paisaje que se disfruta es espectacular, con el cordón montañoso del Aramo Aramo del montañoso cordón el con espectacular, es disfruta se que paisaje Iria Flavia para conocer el sepulcro el conocer para Flavia Iria En el siglo IX viajó desde Oviedo a a Oviedo desde viajó IX siglo el En dirige hacia Oviedo por la Venta del Aire, Caxigal, Los Prietos y El Caserón. El El Caserón. El y Prietos Los Caxigal, Aire, del Venta la por Oviedo hacia dirige Alfonso II, el Casto el II, Alfonso través de un camino que sale a la derecha de la carretera, el peregrino se se peregrino el carretera, la de derecha la a sale que camino un de través pronunciadas, que nos llevan hasta las casas del Picu Llanza. Desde aquí, a a aquí, Desde Llanza. Picu del casas las hasta llevan nos que pronunciadas, Portazgo. En la Manzaneda, el Camino discurre a media ladera, con subidas subidas con ladera, media a discurre Camino el Manzaneda, la En Portazgo. -

5 Year Slurry Outlook As of 2021.Xlsx

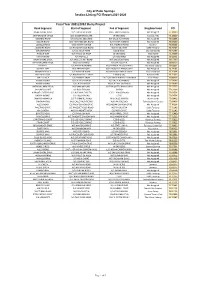

City of Palm Springs Section Listing PCI Report 2021-2026 Fiscal Year 2021/2022 Slurry Project Road Segment Start of Segment End of Segment Neighborhood PCI DINAH SHORE DRIVE W/S CROSSLEY ROAD WEST END OF BRIDGE Not Assigned 75.10000 SNAPDRAGON CIRCLE W/S GOLDENROD LANE W END (CDS) Andreas Hills 75.10000 ANDREAS ROAD E/S CALLE EL SEGUNDO E/S CALLE ALVARADO Not Assigned 75.52638 DILLON ROAD 321'' W/O MELISSA ROAD W/S KAREN AVENUE Not Assigned 75.63230 LOUELLA ROAD S/S LIVMOR AVENUE N/S ANDREAS ROAD Sunmor 75.66065 LEONARD ROAD S/S RACQUET CLUB ROAD N/S VIA OLIVERA Little Tuscany 75.70727 SONORA ROAD E/S EL CIELO ROAD E END (CDS) Los Compadres 75.71757 AMELIA WAY W/S PASEO DE ANZA W END (CDS) Vista Norte 75.78306 TIPTON ROAD N/S HWY 111 S/S RAILROAD Not Assigned 76.32931 DINAH SHORE DRIVE E/S SAN LUIS REY ROAD W/S CROSSLEY ROAD Not Assigned 76.57559 AVENIDA CABALLEROS N/S VISTA CHINO N/S VIA ESCUELA Not Assigned 76.60579 VIA EYTEL E/S AVENIDA PALMAS W/S AVENDA PALOS VERDES The Movie Colony 76.68892 SUNRISE WAY N/S ARENAS ROAD S/S TAHQUITZ CANYON WAY Not Assigned 76.74161 HERMOSA PLACE E/S MISSION ROAD W/S N PALM CANYON DRIVE Old Las Palmas 76.75654 HILLVIEW COVE E/S ANDREAS HILLS DRIVE E END (CSD) Andreas Hills 76.77835 VIA ESCUELA E/S FARRELL DRIVE 130'' E/O WHITEWATER CLUB DRIVE Gene Autry 76.80916 AMADO ROAD E/S CALLE SEGUNDO E/S CALLE ALVARADO Not Assigned 77.54599 AMADO ROAD E/S CALLE ENCILIA W/S CALLE EL SEGUNDO Not Assigned 77.54599 AVENIDA CABALLEROS N/S RAMON ROAD S/S TAHQUITZ CANYON WAY Not Assigned 77.57757 DOLORES COURT LOS -

Coastal Iberia

distinctive travel for more than 35 years TRADE ROUTES OF COASTAL IBERIA UNESCO Bay of Biscay World Heritage Site Cruise Itinerary Air Routing Land Routing Barcelona Palma de Sintra Mallorca SPAIN s d n a sl Lisbon c I leari Cartagena Ba Atlantic PORTUGALSeville Ocean Granada Mediterranean Málaga Sea Portimão Gibraltar Seville Plaza Itinerary* This unique and exclusive nine-day itinerary and small ship u u voyage showcases the coastal jewels of the Iberian Peninsula Lisbon Portimão Gibraltar between Lisbon, Portugal, and Barcelona, Spain, during Granada u Cartagena u Barcelona the best time of year. Cruise ancient trade routes from the October 3 to 11, 2020 Atlantic Ocean to the Mediterranean Sea aboard the Day exclusively chartered, Five-Star LE Jacques Cartier, featuring 1 Depart the U.S. or Canada the extraordinary Blue Eye, the world’s first multisensory, underwater Observation Lounge. This state-of-the-art small 2 Lisbon, Portugal/Embark Le Jacques Cartier ship, launching in 2020, features only 92 ocean-view Suites 3 Portimão, the Algarve, for Lagos and Staterooms and complimentary alcoholic and nonalcoholic beverages and Wi-Fi throughout the ship. Sail up Spain’s 4 Cruise the Guadalquivir River into legendary Guadalquivir River, “the great river,” into the heart Seville, Andalusia, Spain of beautiful Seville, an exclusive opportunity only available 5 Gibraltar, British Overseas Territory on this itinerary and by small ship. Visit Portugal’s Algarve region and Granada, Spain. Stand on the “Top of the Rock” 6 Málaga for Granada, Andalusia, Spain to see the Pillars of Hercules spanning the Strait of Gibraltar 7 Cartagena and call on the Balearic Island of Mallorca. -

Key Facts 2019 Messe Düsseldorf Group

07/2020 EN KEY FACTS 2019 MESSE DÜSSELDORF GROUP www.messe-duesseldorf.com umd2002_00149.indd 3 27.07.20 13:38 CONTENTS 2015–2019 - An overview 04 Business trends 06 Events in Düsseldorf in 2019 08 Areas of expertise 10 International flair 12 Messe Düsseldorf Group 14 Foreign markets 16 Markets & locations 18 Global product portfolios 20 Bodies 24 Düsseldorf as a trade fair location 26 Site plan 28 Keeping in touch & news 30 02 03 umd2002_00149.indd 4 umd2002_00149.indd27.07.20 13:38 5 27.07.20 13:38 2015-2019 – AN OVERVIEW BUSINESS TRENDS 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 Total capacity * m2 304,800 304,800 291,580 291,580 305,727 ° Hall space available m2 261,800 261,800 248,580 248,580 262,727 ° Open-air space available m2 43,000 43,000 43,000 43,000 43,000 Space utilized * m2 (gross) 1,624,789 2,247,486 1,858,831 1,618,357 1,701,618 Space rented out * m2 (net) 891,438 1,308,304 1,162,415 948,782 1,014,145 Fairs and exhibitions * Total 29 31 31 26 29 Self-organized events * 18 19 18 15 18 Partner/guest events * 11 12 13 11 11 Total consolidated sales € million 302.0 442.8 366.9 294.0 378.5 Consolidated sales (Germany) € million 202.1 369.7 302.1 222.6 308.4 Consolidated sales (foreign) € million 99.9 73.1 64.8 71.4 70.1 Consolidated annual profit € million 10.3 58.8 55.0 24.3 56.6 Group workforce 1,207 932 831 831 860 Exhibitors * Total 25,819 32,383 29,210 26,827 29,222 Exhibitors (German-based) 9,189 10,796 9,579 8,462 8,940 Exhibitors (foreign-based) 16,630 21,587 19,631 18,401 20,282 Visitors * Total 1,084,121 1,591,424 1,344,548 1,125,187 1,373,780 Visitors from Germany 802,291 899,322 857,739 782,119 869,458 Visitors from abroad 281,830 692,102 486,809 342,878 504,322 Düsseldorf Congress GmbH Event days 314 308 303 277 240 Events 3,463 3,695 3,461 2,197 1,277 ** Participants 2,355,149 2,269,494 2,508,083 1,632,448 373,490 ** * Düsseldorf exhibition site – due to differences in the numbers of events, the annual figures are only partly comparable.