Genetic Resources of Tropical Legumes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fruits and Seeds of Genera in the Subfamily Faboideae (Fabaceae)

Fruits and Seeds of United States Department of Genera in the Subfamily Agriculture Agricultural Faboideae (Fabaceae) Research Service Technical Bulletin Number 1890 Volume I December 2003 United States Department of Agriculture Fruits and Seeds of Agricultural Research Genera in the Subfamily Service Technical Bulletin Faboideae (Fabaceae) Number 1890 Volume I Joseph H. Kirkbride, Jr., Charles R. Gunn, and Anna L. Weitzman Fruits of A, Centrolobium paraense E.L.R. Tulasne. B, Laburnum anagyroides F.K. Medikus. C, Adesmia boronoides J.D. Hooker. D, Hippocrepis comosa, C. Linnaeus. E, Campylotropis macrocarpa (A.A. von Bunge) A. Rehder. F, Mucuna urens (C. Linnaeus) F.K. Medikus. G, Phaseolus polystachios (C. Linnaeus) N.L. Britton, E.E. Stern, & F. Poggenburg. H, Medicago orbicularis (C. Linnaeus) B. Bartalini. I, Riedeliella graciliflora H.A.T. Harms. J, Medicago arabica (C. Linnaeus) W. Hudson. Kirkbride is a research botanist, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, Systematic Botany and Mycology Laboratory, BARC West Room 304, Building 011A, Beltsville, MD, 20705-2350 (email = [email protected]). Gunn is a botanist (retired) from Brevard, NC (email = [email protected]). Weitzman is a botanist with the Smithsonian Institution, Department of Botany, Washington, DC. Abstract Kirkbride, Joseph H., Jr., Charles R. Gunn, and Anna L radicle junction, Crotalarieae, cuticle, Cytiseae, Weitzman. 2003. Fruits and seeds of genera in the subfamily Dalbergieae, Daleeae, dehiscence, DELTA, Desmodieae, Faboideae (Fabaceae). U. S. Department of Agriculture, Dipteryxeae, distribution, embryo, embryonic axis, en- Technical Bulletin No. 1890, 1,212 pp. docarp, endosperm, epicarp, epicotyl, Euchresteae, Fabeae, fracture line, follicle, funiculus, Galegeae, Genisteae, Technical identification of fruits and seeds of the economi- gynophore, halo, Hedysareae, hilar groove, hilar groove cally important legume plant family (Fabaceae or lips, hilum, Hypocalypteae, hypocotyl, indehiscent, Leguminosae) is often required of U.S. -

I PROCEEDINGS of an INTERNATIONAL SYMPOSIUM

PROCEEDINGS OF AN INTERNATIONAL SYMPOSIUM AND WORKSHOP ON NATIE SEEDS IN RESTORATION OF DRYLAND ECOSYSTEMS NOVEMBER 20 – 23, 2017 STATE OF KUWAIT Organized by Kuwait Institute for Scientific Research (KISR) International Network for Seed-based Restoration (INSR) Sponsored by Kuwait National Focal Point (KNFP) Kuwait Foundation for the Advancement of Sciences (KFAS) Islamic Development Bank (IDB) i PROCEEDINGS OF AN INTERNATIONAL SYMPOSIUM AND WORKSHOP ON NATIE SEEDS IN RESTORATION OF DRYLAND ECOSYSTEMS NOVEMBER 20 – 23, 2017 2017 ii Disclaimer The contents provided in individual papers are the opinion of the author (s) and Editors and KISR hold no responsibility for views expressed. Submissions have been included in the e-version of the proceedings with only minor editing. However, these submissions will be subjected to in-depth technical review/ editing prior to their inclusion in the printed version of symposium proceedings. iii Table of Contents Preface ………………………..……………………………………..………… vii Symposium Committees ……………………………………………..………... ix Section 1: Native Plant Conservation and Selection 1 Assessing the Ex-situ Seed Bank Collections in Conservation of Endangered Native Plants in Kuwait. T. A. Madouh ……………………………………………………………..…... 2 Steps Towards In-situ Conservation for Threatened Plants in Egypt 10 K. A. Omar ………………………………………………………..…………... Conservation and Management of Prosopis cineraria (L) Druce in the State of Qatar. E. M. Elazazi, M. Seyd, R. Al-Mohannadi, M. Al-Qahtani, N. Shahsi, A. Al- 26 Kuwari and M. Al-Marri …………………………………………….………….. The Lonely Tree of Kuwait. 38 M. K. Suleiman, N. R. Bhat, S. Jacob and R. Thomas ……..…………………. Species Restoration Through Ex situ Conservation: Role of Native Seeds in Reclaiming Lands and Environment. S. Saifan …………………………………………………….…………………… 49 Conservation of Native Germplasm Through Seed Banking In the United Arab Emirates: Implications for Seed-Based Restoration S. -

Molecular Cytogenetics of Eurasian Species of the Genus Hedysarum L

plants Article Molecular Cytogenetics of Eurasian Species of the Genus Hedysarum L. (Fabaceae) Olga Yu. Yurkevich 1, Tatiana E. Samatadze 1, Inessa Yu. Selyutina 2, Svetlana I. Romashkina 3, Svyatoslav A. Zoshchuk 1, Alexandra V. Amosova 1 and Olga V. Muravenko 1,* 1 Engelhardt Institute of Molecular Biology, Russian Academy of Sciences, 32 Vavilov St, 119991 Moscow, Russia; [email protected] (O.Y.Y.); [email protected] (T.E.S.); [email protected] (S.A.Z.); [email protected] (A.V.A.) 2 Central Siberian Botanical Garden, SB Russian Academy of Sciences, 101 Zolotodolinskaya St, 630090 Novosibirsk, Russia; [email protected] 3 All-Russian Institute of Medicinal and Aromatic Plants, 7 Green St, 117216 Moscow, Russia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: The systematic knowledge on the genus Hedysarum L. (Fabaceae: Hedysareae) is still incomplete. The species from the section Hedysarum are valuable forage and medicinal resources. For eight Hedysarum species, we constructed the integrated schematic map of their distribution within Eurasia based on currently available scattered data. For the first time, we performed cytoge- nomic characterization of twenty accessions covering eight species for evaluating genomic diversity and relationships within the section Hedysarum. Based on the intra- and interspecific variability of chromosomes bearing 45S and 5S rDNA clusters, four main karyotype groups were detected in the studied accessions: (1) H. arcticum, H. austrosibiricum, H. flavescens, H. hedysaroides, and H. theinum (one chromosome pair with 45S rDNA and one pair bearing 5S rDNA); (2) H. alpinum and one accession of H. hedysaroides (one chromosome pair with 45S rDNA and two pairs bearing 5S rDNA); Citation: Yurkevich, O.Y.; Samatadze, (3) H. -

A Review of the Genus Caesalpinia L.: Emphasis on the Cassane And

J. Med. Plants 2020; 19(76): 1-20 Journal of Medicinal Plants Journal homepage: www.jmp.ir Review Article A review of the genus Caesalpinia L.: emphasis on the cassane and norcassane compounds and cytotoxicity effects Narges Pournaghi1, Farahnaz Khalighi-Sigaroodi1,*, Elahe Safari2, Reza Hajiaghaee1 1 Medicinal Plants Research Center, Institute of Medicinal Plants, ACECR, Karaj, Iran 2 Immunology Department, School of Medicine, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran ARTICLE INFO Abstract Keywords: Background: Many herbal remedies have been used in medical systems for the Caesalpinia genus cure of diseases. One of these important applications is usage of them as cytotoxic Diterpenes agents for the treatment of cancers and tumors. Various studies have been Cassane conducted on several species of Caesalpinia genus including evaluation of Norcassane antimicrobial, antitumor, anti-inflammatory, antipsoriatic, antidiabetic, Cytotoxic antioxidant, antibacterial, immunomodulatory and hypoglycemic activities. Some reports have shown that these plants contain phytochemicals like polyphenols, glycosides, terpenoids, saponins and flavonoids. Objective: The aim of this study was to find species of the Caesalpinia genus containing diterpene compounds with the structure cassane and norcassane with emphasis on cytotoxic properties. Methods: In this study, keywords including Caesalpinia genus, cytotoxic and anticancer effects, and cassane and norcassane compounds were searched in Scopus and Science Direct databases. Results: Thirteen Caesalpinia -

A New Subfamily Classification of The

LPWG Phylogeny and classification of the Leguminosae TAXON 66 (1) • February 2017: 44–77 A new subfamily classification of the Leguminosae based on a taxonomically comprehensive phylogeny The Legume Phylogeny Working Group (LPWG) Recommended citation: LPWG (2017) This paper is a product of the Legume Phylogeny Working Group, who discussed, debated and agreed on the classification of the Leguminosae presented here, and are listed in alphabetical order. The text, keys and descriptions were written and compiled by a subset of authors indicated by §. Newly generated matK sequences were provided by a subset of authors indicated by *. All listed authors commented on and approved the final manuscript. Nasim Azani,1 Marielle Babineau,2* C. Donovan Bailey,3* Hannah Banks,4 Ariane R. Barbosa,5* Rafael Barbosa Pinto,6* James S. Boatwright,7* Leonardo M. Borges,8* Gillian K. Brown,9* Anne Bruneau,2§* Elisa Candido,6* Domingos Cardoso,10§* Kuo-Fang Chung,11* Ruth P. Clark,4 Adilva de S. Conceição,12* Michael Crisp,13* Paloma Cubas,14* Alfonso Delgado-Salinas,15 Kyle G. Dexter,16* Jeff J. Doyle,17 Jérôme Duminil,18* Ashley N. Egan,19* Manuel de la Estrella,4§* Marcus J. Falcão,20 Dmitry A. Filatov,21* Ana Paula Fortuna-Perez,22* Renée H. Fortunato,23 Edeline Gagnon,2* Peter Gasson,4 Juliana Gastaldello Rando,24* Ana Maria Goulart de Azevedo Tozzi,6 Bee Gunn,13* David Harris,25 Elspeth Haston,25 Julie A. Hawkins,26* Patrick S. Herendeen,27§ Colin E. Hughes,28§* João R.V. Iganci,29* Firouzeh Javadi,30* Sheku Alfred Kanu,31 Shahrokh Kazempour-Osaloo,32* Geoffrey C. -

Pollen Grain Morphology in Iranian Hedysareae (Fabaceae)

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.22092/cbj.2012.100413 Pollen grain morphology in Iranian Hedysareae (Fabaceae) F. Ghanavatia* and H. Amirabadizadehb a Seed and Plant Improvement Institute. Karaj, Iran. b Khorasan-e-Razavi Agricultural and Natural Resources Research Center, Mashhad, Iran. *Corresponding author E-mail address: [email protected] Received: October 2011 ABSTRACT F. Ghanavati, and H. Amirabadizadeh. 2012. Pollen grain morphology in Iranian Hedysareae (Fabaceae). Crop Breeding Journal 2(1): 25-33. Pollen grain morphology of 15 taxa of the Hedysareae tribe distributed throughout Iran was studied using light and electron microscopy to identify major taxonomical characteristics of pollen grains. The pollen grains were tricolpate and tricolporate, prolate and perprolate. The ectocolpi were elongated, shallow or deep, narrowing at the poles. The colpus membrane was covered by large granules. Ornamentation was reticulate, and lumina differed in shape and size. In equatorial view, the pollen grains were elongated, elliptic to rectangular-obtuse, while in polar view they were circular, triangular-obtuse or triangular and trilobed. Two pollen types with two tentative subtypes were identified based on ornamentation and polar view. Key words: pollen grains, Hedysareae, ornamentation, taxonomical characteristics INTRODUCTION (15), Laxiflorae (1), Anthyllium (3), Afghanicae (3), rom De Candolle (1825) onward, the Heliobrychis (28) and Hymenobrychis (11). The F taxonomic delimitation of the Hedysarae tribe genus Hedysarum is divided into three sections, has undergone several modifications by various namely Multicaulia (6), Subacaulia (4) and authors (Bentham, 1865; Hutchinson, 1964; Polhill, Crinifera (6) (Rechinger 1984). They are distributed 1981; Choi and Ohashi, 2003; Lock, 2005). all over the country. Recently, Lock (2005) expanded the tribe to 12 The pollen morphology of the Hedysareae has genera including Alhagi Adans., Calophaca Fisch ex not been thoroughly investigated. -

Evidence from Phylogenetic Analyses Based on Five Nuclear and Five Plastid Sequences

RESEARCH ARTICLE Hedysarum L. (Fabaceae: Hedysareae) Is Not Monophyletic ± Evidence from Phylogenetic Analyses Based on Five Nuclear and Five Plastid Sequences Pei-Liang Liu1, Jun Wen2*, Lei Duan3, Emine Arslan4, Kuddisi Ertuğrul4, Zhao- Yang Chang1* a1111111111 1 College of Life Sciences, Northwest A&F University, Yangling, Shaanxi, China, 2 Department of Botany, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington D.C., United States of America, a1111111111 3 Key Laboratory of Plant Resources Conservation and Sustainable Utilization, South China Botanical a1111111111 Garden, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Guangzhou, Guangdong, China, 4 Department of Biology, Faculty a1111111111 of Science, SelcËuk University, Konya, Turkey a1111111111 * [email protected] (ZYC); [email protected] (JW) Abstract OPEN ACCESS Citation: Liu P-L, Wen J, Duan L, Arslan E, Ertuğrul The legume family (Fabaceae) exhibits a high level of species diversity and evolutionary K, Chang Z-Y (2017) Hedysarum L. (Fabaceae: success worldwide. Previous phylogenetic studies of the genus Hedysarum L. (Fabaceae: Hedysareae) Is Not Monophyletic ± Evidence from Hedysareae) showed that the nuclear and the plastid topologies might be incongruent, and Phylogenetic Analyses Based on Five Nuclear and the systematic position of the Hedysarum sect. Stracheya clade was uncertain. In this Five Plastid Sequences. PLoS ONE 12(1): e0170596. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0170596 study, phylogenetic relationships of Hedysarum were investigated based on the nuclear ITS, ETS, PGDH, SQD1, TRPT and the plastid psbA-trnH, trnC-petN, trnL-trnF, trnS-trnG, Editor: Shilin Chen, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College, petN-psbM sequences. Both nuclear and plastid data support two major lineages in Hedy- CHINA sarum: the Hedysarum s.s. -

Vol. 2 Cover. Fruits & Seeds

Fruits and Seeds of United States Department of Genera in the Subfamily Agriculture Agricultural Faboideae (Fabaceae) Research Service Technical Bulletin Number 1890 Volume II December 2003 United States Department of Agriculture Fruits and Seeds of Agricultural Research Genera in the Subfamily Service Technical Bulletin Faboideae (Fabaceae) Number 1890 Volume II Joseph H. Kirkbride, Jr., Charles R. Gunn, and Anna L. Weitzman Fruits of A, Centrolobium paraense E.L.R. Tulasne. B, Laburnum anagyroides F.K. Medikus. C, Adesmia boronoides J.D. Hooker. D, Hippocrepis comosa, C. Linnaeus. E, Campylotropis macrocarpa (A.A. von Bunge) A. Rehder. F, Mucuna urens (C. Linnaeus) F.K. Medikus. G, Phaseolus polystachios (C. Linnaeus) N.L. Britton, E.E. Stern, & F. Poggenburg. H, Medicago orbicularis (C. Linnaeus) B. Bartalini. I, Riedeliella graciliflora H.A.T. Harms. J, Medicago arabica (C. Linnaeus) W. Hudson. Kirkbride is a research botanist, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, Systematic Botany and Mycology Laboratory, BARC West Room 304, Building 011A, Beltsville, MD, 20705-2350 (email = [email protected]). Gunn is a botanist (retired) from Brevard, NC (email = [email protected]). Weitzman is a botanist with the Smithsonian Institution, Department of Botany, Washington, DC. Contents Volume I Procedures .................................................................................................................................................................................... 3 Fruit morphology ......................................................................................................................................................................... -

CBD Fourth National Report

Republic of Yemen Ministry of Water and Environment Environment Protection Authority (EPA ) th 4 National Report Assessing Progress towards the 2010 Target - th The 4 National CBD Report July, 2009 Acknowledgment: In accordance with Article 26 of the Convention and COP decision VIII/14, Parties are required to submit their fourth national report to the Executive Secretary, using the format outlined in the 4 th NR guidelines. Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity, in adopting a Strategic Plan, have committed themselves to achieving, by 2010, a significant reduction in the rate of biodiversity loss at the global, national and regional levels, as a contribution to poverty alleviation and to the benefit of all life on earth. The fourth national report provides an important opportunity to assess progress towards the 2010 target, drawing upon an analysis of the current status and trends in biodiversity and actions taken to implement the Convention at the national level, as well as to consider what further efforts are needed. This report which was prepared over a 6 months period during the preparation time of the 4 th NR. Two workshops and several consultancies meeting ware hold ,in addition to close collaboration with national specialists and research centers. All relevant national agencies and stakeholders were involved in the preparation of the national report, including NGOs, civil society, and local communities, privet sectors , and the media. We gratefully thank all of the individuals, relevant agencies, stakeholders and local communities who have provided input to this report including the national consultant's team under the supervision of Mr. -

Hedysarum Alamutense (Fabaceae-Hedysareae), a New Species from Iran, and Its Phylogenetic Position Based on Molecular Data

Turkish Journal of Botany Turk J Bot (2019) 43: 386-394 http://journals.tubitak.gov.tr/botany/ © TÜBİTAK Research Article doi:10.3906/bot-1806-50 Hedysarum alamutense (Fabaceae-Hedysareae), a new species from Iran, and its phylogenetic position based on molecular data 1 1, 2 2 Haniyeh NAFISI , Shahrokh KAZEMPOUR-OSALOO *, Valiollah MOZAFFARIAN , Mohammad AMINI-RAD 1 Department of Plant Biology, Faculty of Biological Sciences, Tarbiat Modares University, Tehran, Iran 2 Research Institute of Forests and Rangelands, Agricultural Research, Education, and Extension Organization (AREEO), Tehran, Iran Received: 25.06.2018 Accepted/Published Online: 14.01.2019 Final Version: 06.05.2019 Abstract: Hedysarum alamutense, a new species in the tribe Hedysareae DC. (Fabaceae), is described and illustrated. It belongs to the traditionally recognized Hedysarum L. section Multicaulia (Boiss.) B.Fedtsch., which extends over the West Alborz Mountains in northern Iran. This species is characterized by greenish stems and corolla persisting in fruiting stage and has mostly 1–2-jointed, unarmed, biconvex pods with short hairs becoming bald early, and flattened margins. Phylogenetic analyses of molecular data clearly unite this species with H. formosum Fisch. & C.A.Mey. ex Basin. The new species is characterized by 4 singleton nucleotide substitutions, suggesting it as a distinct taxon. Phylogenetic inferences are consistent with the interpretations of morphological features. Moreover, the lack of nucleotide variation among individual samples of H. formosum indicated that the species has not been diversified at the population level and reinforced our findings. Keywords: Alborz Mountains, Hedysarum, phylogeny, section Multicaulia, taxonomy 1. Introduction (Boissier, 1872; Rechinger, 1952; Chrtková-Žertová, 1968; The genus Hedysarum L., encompassing ca. -

Download Download

The Journal of Threatened Taxa (JoTT) is dedicated to building evidence for conservaton globally by publishing peer-reviewed artcles OPEN ACCESS online every month at a reasonably rapid rate at www.threatenedtaxa.org. All artcles published in JoTT are registered under Creatve Commons Atributon 4.0 Internatonal License unless otherwise mentoned. JoTT allows unrestricted use, reproducton, and distributon of artcles in any medium by providing adequate credit to the author(s) and the source of publicaton. Journal of Threatened Taxa Building evidence for conservaton globally www.threatenedtaxa.org ISSN 0974-7907 (Online) | ISSN 0974-7893 (Print) Communication Legumes (Angiosperms: Fabaceae) of Bagalkot District, Karnataka, India Jagdish Dalavi, Ramesh Pujar, Sharad Kambale, Varsha Jadhav-Rathod & Shrirang Yadav 26 April 2021 | Vol. 13 | No. 5 | Pages: 18283–18296 DOI: 10.11609/jot.6394.13.5.18283-18296 For Focus, Scope, Aims, and Policies, visit htps://threatenedtaxa.org/index.php/JoTT/aims_scope For Artcle Submission Guidelines, visit htps://threatenedtaxa.org/index.php/JoTT/about/submissions For Policies against Scientfc Misconduct, visit htps://threatenedtaxa.org/index.php/JoTT/policies_various For reprints, contact <[email protected]> The opinions expressed by the authors do not refect the views of the Journal of Threatened Taxa, Wildlife Informaton Liaison Development Society, Zoo Outreach Organizaton, or any of the partners. The journal, the publisher, the host, and the part- Publisher & Host ners are not responsible for the accuracy -

Microsoft Word

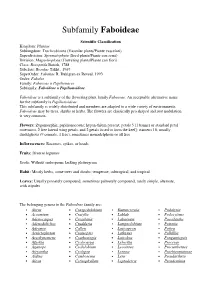

Subfamily Faboideae Scientific Classification Kingdom: Plantae Subkingdom: Tracheobionta (Vascular plants/Piante vascolari) Superdivision: Spermatophyta (Seed plants/Piante con semi) Division: Magnoliophyta (Flowering plants/Piante con fiori) Class: Rosopsida Batsch, 1788 Subclass: Rosidae Takht., 1967 SuperOrder: Fabanae R. Dahlgren ex Reveal, 1993 Order: Fabales Family: Fabaceae o Papilionacee Subfamily: Faboideae o Papilionoideae Faboideae is a subfamily of the flowering plant family Fabaceae . An acceptable alternative name for the subfamily is Papilionoideae . This subfamily is widely distributed and members are adapted to a wide variety of environments. Faboideae may be trees, shrubs or herbs. The flowers are classically pea shaped and root nodulation is very common. Flowers: Zygomorphic, papilionaceous; hypan-thium present; petals 5 [1 banner or standard petal outermost, 2 free lateral wing petals, and 2 petals fused to form the keel]; stamens 10, usually diadelphous (9 connate, 1 free), sometimes monadelphous or all free Inflorescences: Racemes, spikes, or heads Fruits: Diverse legumes Seeds: Without endosperm; lacking pleurogram Habit: Mostly herbs, some trees and shrubs; temperate, subtropical, and tropical Leaves: Usually pinnately compound, sometimes palmately compound, rarely simple, alternate, with stipules The belonging genera to the Faboideae family are: • Abrus • Craspedolobium • Kummerowia • Podalyria • Acosmium • Cratylia • Lablab • Podocytisus • Adenocarpus • Crotalaria • Laburnum • Poecilanthe • Adenodolichos • Cruddasia