Lincoln in the Bardo: “Uh, NOT a Historical Novel”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Curious Paternity of Abraham Lincoln

GREAT SMOKY MOUNTAINS Judge for yourself: does that famous jawline reveal Lincoln’s true paternity? Spring 2008 olloquyVolume 9 • Number 1 CT HE U NIVERSI T Y OF T ENNESSEE L IBRARIES The Curious Paternity of Abraham Lincoln Great Smoky Mountains Colloquy WAS HE A SMOKY MOUNTAIN BOY? is a newsletter published by umors have persisted since the late 19th century that Abraham Lincoln The University of Tennessee was not the son of Thomas Lincoln but was actually the illegitimate Libraries. Rson of a Smoky Mountain man, Abram Enloe. The story of Lincoln’s Co-editors: paternity was first related in 1893 article in theCharlotte Observer by a writer Anne Bridges who called himself a “Student of History.” The myth Ken Wise was later perpetuated by several other Western North Carolina writers, most notably James H. Cathey in a Correspondence and book entitled Truth Is Stranger than Fiction: True Genesis change of address: GSM Colloquy of a Wonderful Man published first in 1899. Here is the 152D John C. Hodges Library story as it was told by Cathey and “Student of History.” The University of Tennessee Around 1800, Abram Enloe, a resident of Rutherford Knoxville, TN 37996-1000 County, N. C., brought into his household an orphan, 865/974-2359 Nancy Hanks, to be a family servant. She was about ten 865/974-9242 (fax) or twelve years old at the time. When Nancy was about Email: [email protected] eighteen or twenty, the family moved to Swain County, Web: www.lib.utk.edu/smokies/ settling in Oconoluftee at the edge of the Smokies. -

Social Studies Mini-Unit the Reconstruction Era

Social Studies Mini-Unit The Reconstruction Era Goal: These lessons focus on both national and local personal narratives from the Reconstruction Period. Let these stories help you decide what characteristics a community, a leader or an individual would need during this time period. Materials: Computer with internet, writing materials Instruction: Following the Civil War, the Reconstruction Period began within our country an immense new chapter for social reform with the definition of freedom for debate. People began to rebuild the South and try to unite the states, but newly freed persons were seeking ways to build their own futures in a still hostile environment. Dive into these lessons to learn more about individuals of the time. Lesson 1: Lincoln Originals This online exhibition features digital scans of primary historical documents in Abraham Lincoln’s hand, or signed by him, drawn from the diverse manuscript holdings at Cincinnati Museum Center. 1. Explore the Lincoln Originals Online Exhibit 2. Read the Emancipation Proclamation Fact Sheet [linked here] a. Extension: Review the 13th, 14th and 15th Amendments which are considered the Reconstruction Amendments. 3. Journal Entry: What characteristics defined President Lincoln? a. Write a persuasive argument in the form of a letter addressed to a past president (or the current administration) outlining an important issue and what you believe the correct course of action is and why. Cite evidence to support your case. 4. Extension Option: Research Lincoln’s Ten-Percent Plan, a plan for reconstruction, versus the Wade-Davis Bill, which was a Radical Republican plan for reconstruction. Explore the similarities and differences of these two documents. -

Who Freed Athens? J

Ancient Greek Democracy: Readings and Sources Edited by Eric W. Robinson Copyright © 2004 by Blackwell Publishing Ltd The Beginnings of the Athenian Democracv: Who Freed Athens? J Introduction Though the very earliest democracies lildy took shape elsewhere in Greece, Athens embraced it relatively early and would ultimately become the most famous and powerful democracy the ancient world ever hew. Democracy is usually thought to have taken hold among the Athenians with the constitutional reforms of Cleisthenes, ca. 508/7 BC. The tyrant Peisistratus and later his sons had ruled Athens for decades before they were overthrown; Cleisthenes, rallying the people to his cause, made sweeping changes. These included the creation of a representative council (bode)chosen from among the citizens, new public organizations that more closely tied citizens throughout Attica to the Athenian state, and the populist ostracism law that enabled citizens to exile danger- ous or undesirable politicians by vote. Beginning with these measures, and for the next two centuries or so with only the briefest of interruptions, democracy held sway at Athens. Such is the most common interpretation. But there is, in fact, much room for disagree- ment about when and how democracy came to Athens. Ancient authors sometimes refer to Solon, a lawgiver and mediator of the early sixth century, as the founder of the Athenian constitution. It was also a popular belief among the Athenians that two famous “tyrant-slayers,” Harmodius and Aristogeiton, inaugurated Athenian freedom by assas- sinating one of the sons of Peisistratus a few years before Cleisthenes’ reforms - though ancient writers take pains to point out that only the military intervention of Sparta truly ended the tyranny. -

In the Mix: the Potential Convergence of Literature and New Media in Jonathan Lethem’S ‘The Ecstasy of Influence’

In the Mix: The Potential Convergence of Literature and New Media in Jonathan Lethem’s ‘The Ecstasy of Influence’ Zara Dinnen Journal of Narrative Theory, Volume 42, Number 2, Summer 2012, pp. 212-230 (Article) Published by Eastern Michigan University DOI: https://doi.org/10.1353/jnt.2012.0009 For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/488160 Access provided by University of Birmingham (8 Jan 2017 15:33 GMT) In the Mix: The Potential Convergence of Literature and New Media in Jonathan Lethem’s ‘The Ecstasy of Influence’ Zara Dinnen This article considers the reinscription of certain ideas of authorship in a digital age, when literary texts are produced through a medium that sub- stantiates and elevates composite forms and procedures over distinct orig- inal versions. Digital media technologies reconfigure the way in which we apply such techniques as collage, quotation, and plagiarism, comprising as they do procedural code that is itself a mix, a mash-up, a version of a ver- sion of a version. In the contemporary moment, the predominance of a medium that effaces its own means of production (behind interfaces, ‘pages,’ or ‘sticky notes’) suggests that we may no longer fetishize the master-copy, or the originary script, and that we once again need to re- theorize the term ‘author,’ asking for example how we can instantiate such a notion through a medium that abstracts the indelible and rewrites it as in- finitely reproducible and malleable.1 If the majority of texts written today—be they literary, academic, or journalistic—are first produced on a computer, it is increasingly necessary to think about how the ‘author’ in that instance may be not a rigid point of origin, but instead a relay for al- ternative modes of production, particularly composite modes of produc- tion, assuming such positions as ‘scripter,’ ‘producer,’ or even ‘DJ.’ By embarking on this path of enquiry, this article attempts to produce a JNT: Journal of Narrative Theory 42.2 (Summer 2012): 212–230. -

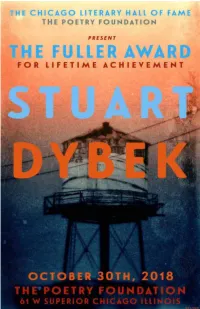

Stuartdybekprogram.Pdf

1 Genius did not announce itself readily, or convincingly, in the Little Village of says. “I met every kind of person I was going to meet by the time I was 12.” the early 1950s, when the first vaguely artistic churnings were taking place in Stuart’s family lived on the first floor of the six-flat, which his father the mind of a young Stuart Dybek. As the young Stu's pencil plopped through endlessly repaired and upgraded, often with Stuart at his side. Stuart’s bedroom the surface scum into what local kids called the Insanitary Canal, he would have was decorated with the Picasso wallpaper he had requested, and from there he no idea he would someday draw comparisons to Ernest Hemingway, Sherwood peeked out at Kashka Mariska’s wreck of a house, replete with chickens and Anderson, Theodore Dreiser, Nelson Algren, James T. Farrell, Saul Bellow, dogs running all over the place. and just about every other master of “That kind of immersion early on kind of makes everything in later life the blue-collar, neighborhood-driven boring,” he says. “If you could survive it, it was kind of a gift that you didn’t growing story. Nor would the young Stu have even know you were getting.” even an inkling that his genius, as it Stuart, consciously or not, was being drawn into the world of stories. He in place were, was wrapped up right there, in recognizes that his Little Village had what Southern writers often refer to as by donald g. evans that mucky water, in the prison just a storytelling culture. -

Lincoln in the Bardo

Get hundreds more LitCharts at www.litcharts.com Lincoln in the Bardo INTRODUCTION RELATED LITERARY WORKS Lincoln in the Bardo borrows the term “Bardo” from The Bardo BRIEF BIOGRAPHY OF GEORGE SAUNDERS Thodol, a Tibetan text more widely known as The Tibetan Book of . Tibetan Buddhists use the word “Bardo” to refer to George Saunders was born in 1958 in Amarillo, Texas, but he the Dead grew up in Chicago. When he was eighteen, he attended the any transitional period, including life itself, since life is simply a Colorado School of Mines, where he graduated with a transitional state that takes place after a person’s birth and geophysical engineering degree in 1981. Upon graduation, he before their death. Written in the fourteenth century, The worked as a field geophysicist in the oil-fields of Sumatra, an Bardo Thodol is supposed to guide souls through the bardo that island in Southeast Asia. Perhaps because the closest town was exists between death and either reincarnation or the only accessible by helicopter, Saunders started reading attainment of nirvana. In addition, Lincoln in the Bardo voraciously while working in the oil-fields. A eary and a half sometimes resembles Dante Alighieri’s Divine Comedy, since later, he got sick after swimming in a feces-contaminated river, Saunders’s deceased characters deliver long monologues so he returned to the United States. During this time, he reminiscent of the self-interested speeches uttered by worked a number of hourly jobs before attending Syracuse condemned sinners in The Inferno. Taken together, these two University, where he earned his Master’s in Creative Writing. -

Myth and Carnival in Robert Coover's the Public Burning

ROBERTO MARIA DAINOTTO Myth and Carnival in Robert Coover's The Public Burning Certain situations in Coover's fictions seem to conspire with a sense of impending disaster, which we have visited upon us from day to day. We have had, in that sense, an unending sequence of apocalypses, long before Christianity began and up to the present... in a lot of contemporary fiction there's a sense of foreboding disaster which is part of the times, just like self reflexive fictions. (Coover 1983, 78) As allegory, the trope of the apocalypse—a postmodern version of the Aristotelian tragic catastrophe—stands at the center of Coover's choice of content, his method of treating his materials, and his view of writing. In his fictions, one observes desperate people caught in religious nightmares leading to terrible catastrophes, a middle-aged man whose life is sacrificed at the altar of an imaginary baseball game, beautiful women repeatedly killed in the Gothic intrigues of Gerald's Party, and other hints and omens of death and annihilation. And what about the Rosenbergs, whom the powers that be "determined to burn... in New York City's Times Square on the night of their fourteenth wedding anniversary, Thursday, June 18, 1953"(PB 3)?1 In The Public Burning, apocalypse becomes holocaust—quite literally, the Greek holokauston, a "sacrifice consumed by fire." What proves interesting from a narrative point of view is that Coover makes disaster, apocalypse and holocaust part of the materials of the fictions" of the times"—which he calls" self-reflexive fictions." But what is the relation between genocide, human annihilation, and self-reflexive fictions? How do fictions" of the times" reflect holocaust? Larry McCaffery suggests: 6 Dainotto in most of Coover's fiction there exists a tension between the process of man creating his fictions and his desire to assert that his systems have an independent existence of their own. -

A Quest for Historical Truth in Postmodernist American Fiction

A Quest For Historical Truth in Postmodernist American Fiction Sung, Kyung-Jun I Since the 1970's there have been ongoing debates about the nature of postmodernist American fiction. Many of the critics involved in these debates tend to think of postmoder- nist American fiction as metafiction, surfiction, or fabulation, emphasizing the self-reflexive characteristic of these fictions. We can see this trend of criticism reflected in the titles of books: Robert Scholes's Fabulation and Metajction (1979), Larry McCaffery's The Metajctional Muse (1982), and Patricia Waugh's MetaJiction (1984), which are regarded as important criticisms of postmodernist American fiction. Without denying that the metafictional trend is a conspicuous characteristic in postmodernist American fiction, it also appears to be correct to state that postmodernist American writers' concern with the social reality in which they live is an equal factor in the shaping of their works. When we examine postmodernist American fiction more closely, we find that it, though metafictional and self-reflexive in form, starts with paying serious attention to the cultural, social and political circumstances of America which have changed rapidly since the 1960's. This fact that postmodernist American writers pay close attention to the current problems and troubles of importance in America is exemplified concretely in the themes of their works. For example, E.L. Doctorow's The Book of Daniel (1971) and Robert Coover's The Public Burning (1977) deal with the case of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg who were victimized in the whirlpool of the Cold War; Thomas Pynchon's V. (1964) and Richard Brautigan's Trout Fishing in America (1967) focus on the the disorder and desolation of modern American society; John Barth's Giles Goat-Boy (1966) analyzes the ideological conflict between Capitalism and Communism and the social problems in the electronic age; Pynchon's Gravity's Rainbow (1973) gets at the heart of the nuclear war and, as a result of it, the fall of the world. -

Wisdom Extracted Hybrid

Wisdom Extracted Hybrid Written by: Eric Chang, Alyssa Jorgensen (VT), Meredith Seaberg (VCU), Joshua Uy (VT), Thomas Davidson (VT), Alia Wilson (VT) Edited by: Eric Chang (while potentially under the influence of very strong painkillers after getting my wisdom teeth removed, sorry in advance!) Special thanks to: Nathalie Unico and Jiyun Chang for playtesting part of the set, and Dr. Cyr for pulling my g-darn teeth out and causing the pain for me to write these questions. Packet 3 Toss-ups 1. In a short story by this author, Callie chains her son Bo to a tree to prevent him from running away and jumping between cars on the interstate, and another story by him centers around Abnesti creating a drug that when administered creates a strong sexual attraction and causes users to fall deeply in love. Those stories, (*) “Puppy” and “Escape from Spiderhead,” are collected in this author’s Tenth of December collection, which was published before his novel that takes place after the death of Willie, the son of the 16th president, as he wanders around the Tibetan “intermediate state.” For 10 points, name this American writer of CivilWarLand in Bad Decline, who won the 2017 Man Booker Prize for his novel Lincoln in the Bardo. ANSWER: George Saunders <Eric Chang> 2. An Ohio minister planned to sue the host of this televised event due to its revealing nature that put him “in danger of hellfire.” One singer from this event wrapped a rope around her wrists while belly dancing to “Ojos Así,” and a choir of young girls sang “Let’s Get Loud” for this event. -

Emancipation Proclamation

Abraham Lincoln and the emancipation proclamation with an introduction by Allen C. Guelzo Abraham Lincoln and the emancipation proclamation A Selection of Documents for Teachers with an introduction by Allen C. Guelzo compiled by James G. Basker and Justine Ahlstrom New York 2012 copyright © 2008 19 W. 44th St., Ste. 500, New York, NY 10036 www.gilderlehrman.org isbn 978-1-932821-87-1 cover illustrations: photograph of Abraham Lincoln, by Andrew Gard- ner, printed by Philips and Solomons, 1865 (Gilder Lehrman Collection, GLC05111.01.466); the second page of Abraham Lincoln’s draft of the Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation, September 22, 1862 (New York State Library, see pages 20–23); photograph of a free African American family in Calhoun, Alabama, by Rich- ard Riley, 19th century (GLC05140.02) Many of the documents in this booklet are unique manuscripts from the gilder leh- rman collection identified by the following accession numbers: p8, GLC00590; p10, GLC05302; p12, GLC01264; p14, GLC08588; p27, GLC00742; p28 (bottom), GLC00493.03; p30, GLC05981.09; p32, GLC03790; p34, GLC03229.01; p40, GLC00317.02; p42, GLC08094; p43, GLC00263; p44, GLC06198; p45, GLC06044. Contents Introduction by Allen C. Guelzo ...................................................................... 5 Documents “The monstrous injustice of slavery itself”: Lincoln’s Speech against the Kansas-Nebraska Act in Peoria, Illinois, October 16, 1854. 8 “To contribute an humble mite to that glorious consummation”: Notes by Abraham Lincoln for a Campaign Speech in the Senate Race against Stephen A. Douglas, 1858 ...10 “I have no lawful right to do so”: Lincoln’s First Inaugural Address, March 4, 1861 .........12 “Adopt gradual abolishment of slavery”: Message from President Lincoln to Congress, March 6, 1862 ...........................................................................................14 “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude . -

After Fiction? Democratic Imagination in an Age of Facts

After Fiction? Democratic Imagination in an Age of Facts §1 Philosophical reflection on the relationship between democracy and literature tends to take the novel as its privileged object of analysis, albeit for different reasons in the Francophone and Anglophone contexts. For Jacques Rancière, the genre (or rather non-genre) of the novel exemplifies the democratic disturbance that is the very principle of literature: “La maladie démocratique et la performance littéraire ont même principe: cette vie de la lettre muette-bavarde, de la lettre démocratique qui perturbe tout rapport ordonné entre l’ordre du discours et l’ordre des états”1. In contrast to this model of disruption to the existing order of representations, Anglophone philosophers often locate the democratic dimension of the novel in its promotion of shared understanding, a kind of training in liberal solidarity through imaginative identification. §2 My aim here is not to detail the similarities and differences between these approaches, but rather to confront these views with the current instability of the link between the genre of the novel and democratic community. The literary field in the 21st century is increasingly troubled by a new kind of democratic disorder. With the proliferation of information and narrative forms, factual modes of writing increasingly become the privileged site of literature’s engagement with the real. This “factual turn”, which in the Anglophone world has led to large claims for the powers of literary nonfiction, is also visible, although differently articulated, in contemporary French literature. We may wonder whether this development signals a renewed involvement of literature in public discourse, or a failure of the imaginative capacity to transform the actual. -

What Does It Mean to Write Fiction? What Does Fiction Refer To?

What Does It Mean to Write Fiction? What Does Fiction Refer to? Timothy Bewes Abstract Through an engagement with recent American fiction, this article explores the possibility that the creative procedures and narrative modes of literary works might directly inform our critical procedures also. Although this is not detailed in the piece, one of the motivations behind this project is the idea that such pro- cedures may act as a technology to enable critics to escape the place of the “com- mentator” that Michel Foucault anathematizes in his reflections on critical dis- course (for example, in his 1970 lecture “The Order of Discourse”). The article not only theorizes but attempts to enact these possibilities by inhabiting a subjective register located between fiction and criticism—a space that, in different ways, is also inhabited by the two literary works under discussion, Renee Gladman’s To After That and Colson Whitehead’s novel Zone One. (Gladman’s work also provides the quotations that subtitle each half of the essay.) Readers may notice a subtle but important shift of subjective positionality that takes place between sections I and II. 1 “What Does It Mean to Write Fiction? What Does Fiction Refer to?” These two questions are not mine—which means that they are not yours, either. They are taken from a work of fiction entitled To After That by the American writer Renee Gladman. I hesitate to call them a quotation, for, although they appear in Gladman’s book, the questions do not exactly belong to her narrator; or rather, they do not belong to the moment of Gladman’s narration.