Relationships Between Nest-Dwelling Lepidoptera and Their Owl Hosts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Table of Contents

Table of Contents Plenary Using ecological site information to evaluate the probabilities and effects of Joel Brown Page 6 restoration Andrew Campbell The last four decades of land repair in Australia: what have we learnt? Page 6 Kingsley Dixon Restoring the island continent Page 6 Restoring species rich and functionally complex grassy communities – feasible Paul Gibson-Roy Page 7 or fiction? Pollination services in restoration – comparing intact and degraded Caroline Gross Page 7 communities provides assembly rules for restoring cleared landscapes Where to from here? Challenges for restoration and revegetation in a fast- Richard Hobbs Page 8 changing world Thomas Jones Ecosystem restoration: recent advances in theory and practice Page 8 Tein McDonald National standards for the practice of ecological restoration in Australia Page 9 David Norton Upscaling the restoration effort – a New Zealand perspective Page 9 A changing climate, considerations for future ecological management and Kristen Williams Page 10 restoration Keynote Linda Broadhurst Restoration genetics – how far have we come and we are we going? Page 10 Turquoise is the new green: riparian restoration and revegetation in the Samantha Capon Page 10 Anthropocene Carla Catterall Fauna: passengers and drivers in vegetation restoration Page 11 Veronica Doerr Landscape connectivity: do we have the right science to make a difference? Page 11 Josh Dorrough Grazing management for biodiversity conservation Page 12 Invasive species and their impacts on agri-ecosystems: issues and solutions -

SYSTEMATICS of the MEGADIVERSE SUPERFAMILY GELECHIOIDEA (INSECTA: LEPIDOPTEA) DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of T

SYSTEMATICS OF THE MEGADIVERSE SUPERFAMILY GELECHIOIDEA (INSECTA: LEPIDOPTEA) DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Sibyl Rae Bucheli, M.S. ***** The Ohio State University 2005 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Dr. John W. Wenzel, Advisor Dr. Daniel Herms Dr. Hans Klompen _________________________________ Dr. Steven C. Passoa Advisor Graduate Program in Entomology ABSTRACT The phylogenetics, systematics, taxonomy, and biology of Gelechioidea (Insecta: Lepidoptera) are investigated. This superfamily is probably the second largest in all of Lepidoptera, and it remains one of the least well known. Taxonomy of Gelechioidea has been unstable historically, and definitions vary at the family and subfamily levels. In Chapters Two and Three, I review the taxonomy of Gelechioidea and characters that have been important, with attention to what characters or terms were used by different authors. I revise the coding of characters that are already in the literature, and provide new data as well. Chapter Four provides the first phylogenetic analysis of Gelechioidea to include molecular data. I combine novel DNA sequence data from Cytochrome oxidase I and II with morphological matrices for exemplar species. The results challenge current concepts of Gelechioidea, suggesting that traditional morphological characters that have united taxa may not be homologous structures and are in need of further investigation. Resolution of this problem will require more detailed analysis and more thorough characterization of certain lineages. To begin this task, I conduct in Chapter Five an in- depth study of morphological evolution, host-plant selection, and geographical distribution of a medium-sized genus Depressaria Haworth (Depressariinae), larvae of ii which generally feed on plants in the families Asteraceae and Apiaceae. -

Entomology of the Aucklands and Other Islands South of New Zealand: Lepidoptera, Ex Cluding Non-Crambine Pyralidae

Pacific Insects Monograph 27: 55-172 10 November 1971 ENTOMOLOGY OF THE AUCKLANDS AND OTHER ISLANDS SOUTH OF NEW ZEALAND: LEPIDOPTERA, EX CLUDING NON-CRAMBINE PYRALIDAE By J. S. Dugdale1 CONTENTS Introduction 55 Acknowledgements 58 Faunal Composition and Relationships 58 Faunal List 59 Key to Families 68 1. Arctiidae 71 2. Carposinidae 73 Coleophoridae 76 Cosmopterygidae 77 3. Crambinae (pt Pyralidae) 77 4. Elachistidae 79 5. Geometridae 89 Hyponomeutidae 115 6. Nepticulidae 115 7. Noctuidae 117 8. Oecophoridae 131 9. Psychidae 137 10. Pterophoridae 145 11. Tineidae... 148 12. Tortricidae 156 References 169 Note 172 Abstract: This paper deals with all Lepidoptera, excluding the non-crambine Pyralidae, of Auckland, Campbell, Antipodes and Snares Is. The native resident fauna of these islands consists of 42 species of which 21 (50%) are endemic, in 27 genera, of which 3 (11%) are endemic, in 12 families. The endemic fauna is characterised by brachyptery (66%), body size under 10 mm (72%) and concealed, or strictly ground- dwelling larval life. All species can be related to mainland forms; there is a distinctive pre-Pleistocene element as well as some instances of possible Pleistocene introductions, as suggested by the presence of pairs of species, one member of which is endemic but fully winged. A graph and tables are given showing the composition of the fauna, its distribution, habits, and presumed derivations. Host plants or host niches are discussed. An additional 7 species are considered to be non-resident waifs. The taxonomic part includes keys to families (applicable only to the subantarctic fauna), and to genera and species. -

Lepidoptera of North America 5

Lepidoptera of North America 5. Contributions to the Knowledge of Southern West Virginia Lepidoptera Contributions of the C.P. Gillette Museum of Arthropod Diversity Colorado State University Lepidoptera of North America 5. Contributions to the Knowledge of Southern West Virginia Lepidoptera by Valerio Albu, 1411 E. Sweetbriar Drive Fresno, CA 93720 and Eric Metzler, 1241 Kildale Square North Columbus, OH 43229 April 30, 2004 Contributions of the C.P. Gillette Museum of Arthropod Diversity Colorado State University Cover illustration: Blueberry Sphinx (Paonias astylus (Drury)], an eastern endemic. Photo by Valeriu Albu. ISBN 1084-8819 This publication and others in the series may be ordered from the C.P. Gillette Museum of Arthropod Diversity, Department of Bioagricultural Sciences and Pest Management Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO 80523 Abstract A list of 1531 species ofLepidoptera is presented, collected over 15 years (1988 to 2002), in eleven southern West Virginia counties. A variety of collecting methods was used, including netting, light attracting, light trapping and pheromone trapping. The specimens were identified by the currently available pictorial sources and determination keys. Many were also sent to specialists for confirmation or identification. The majority of the data was from Kanawha County, reflecting the area of more intensive sampling effort by the senior author. This imbalance of data between Kanawha County and other counties should even out with further sampling of the area. Key Words: Appalachian Mountains, -

Lepidoptera: Tineidae) from Chinazoj 704 1..14

Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 2011, 163, 1–14. With 5 figures A revision of the Monopis monachella species complex (Lepidoptera: Tineidae) from Chinazoj_704 1..14 GUO-HUA HUANG1*, LIU-SHENG CHEN2, TOSHIYA HIROWATARI3, YOSHITSUGU NASU4 and MING WANG5 1Institute of Entomology, College of Bio-safety Science and Technology, Hunan Agricultural University, Changsha 410128, Hunan Province, China. E-mail: [email protected] 2College of Agriculture, Shihezi University, Shihezi 832800, Xinjiang, China. E-mail: [email protected] 3Entomological Laboratory, Graduate School of Life and Environmental Sciences, Osaka Prefecture University, Sakai 599-8531, Osaka, Japan. E-mail: [email protected] 4Osaka Plant Protection Office: Habikino, Osaka 583-0862, Japan. E-mail: [email protected] 5Department of Entomology, South China Agricultural University, Guangzhou 510640, Guangdong Province, China. E-mail: [email protected] Received 19 March 2010; revised 21 September 2010; accepted for publication 24 September 2010 The Monopis monachella species complex from China is revised, and its relationship to other species complexes of the genus Monopis is discussed with reference to morphological, and molecular evidence. Principal component analysis on all available specimens provided supporting evidence for the existence of three species, one of which is described as new: Monopis iunctio Huang & Hirowatari sp. nov. All species are either diagnosed or described, and illustrated, and information is given on their distribution and host range. Additional information is given on the biology and larval stages of Monopis longella. A preliminary phylogenetic study based on mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit I gene (CO1) sequence data and a key to the species of the M. -

Report-VIC-Croajingolong National Park-Appendix A

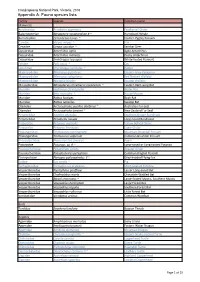

Croajingolong National Park, Victoria, 2016 Appendix A: Fauna species lists Family Species Common name Mammals Acrobatidae Acrobates pygmaeus Feathertail Glider Balaenopteriae Megaptera novaeangliae # ~ Humpback Whale Burramyidae Cercartetus nanus ~ Eastern Pygmy Possum Canidae Vulpes vulpes ^ Fox Cervidae Cervus unicolor ^ Sambar Deer Dasyuridae Antechinus agilis Agile Antechinus Dasyuridae Antechinus mimetes Dusky Antechinus Dasyuridae Sminthopsis leucopus White-footed Dunnart Felidae Felis catus ^ Cat Leporidae Oryctolagus cuniculus ^ Rabbit Macropodidae Macropus giganteus Eastern Grey Kangaroo Macropodidae Macropus rufogriseus Red Necked Wallaby Macropodidae Wallabia bicolor Swamp Wallaby Miniopteridae Miniopterus schreibersii oceanensis ~ Eastern Bent-wing Bat Muridae Hydromys chrysogaster Water Rat Muridae Mus musculus ^ House Mouse Muridae Rattus fuscipes Bush Rat Muridae Rattus lutreolus Swamp Rat Otariidae Arctocephalus pusillus doriferus ~ Australian Fur-seal Otariidae Arctocephalus forsteri ~ New Zealand Fur Seal Peramelidae Isoodon obesulus Southern Brown Bandicoot Peramelidae Perameles nasuta Long-nosed Bandicoot Petauridae Petaurus australis Yellow Bellied Glider Petauridae Petaurus breviceps Sugar Glider Phalangeridae Trichosurus cunninghami Mountain Brushtail Possum Phalangeridae Trichosurus vulpecula Common Brushtail Possum Phascolarctidae Phascolarctos cinereus Koala Potoroidae Potorous sp. # ~ Long-nosed or Long-footed Potoroo Pseudocheiridae Petauroides volans Greater Glider Pseudocheiridae Pseudocheirus peregrinus -

How to Control Soil Insects with Beneficial Nematodes

How to Control Soil Insects with Beneficial Nematodes Ed Lewis Department of Entomology and Nematology University of California, Davis Using Microbials in IPM • Do not have to change everything about crop management • Many microbial insecticides fit into current production plans with minimal effort and change • They require specialized information about their use Insect pathogens can be effective • Naturally occur – Even in intensively managed systems • Have an impact on insect populations at natural levels Necessary information: Products • Shelf life • Storage conditions • Resting stage? • Viability in field • Host range • Time to kill • What does an infected insect look like? Recognized Species of Entomopathogenic Nematodes H. bacteriophora H. marelatus H. brevicaudis H. megidis H. hawaiiensis H. zealandica H. indica H. argentinensis S. kraussei S. karii S. arenarium S. kushidai S. bicornutum S. longicaudum S. carpocapsae S. monticolum S. caudatum S. neocurtillae S. ceratophorum S. oregonense S. cubanum S. puertoricense S. feltiae S. rarum S. glaseri S. riobrave S. intermedium S. ritteri S. affine S. scapterisci Infective Juveniles • Resistant to Environmental Extremes • Only Function is to Find A New Host • No Feeding • No Development • No Reproduction • Only Life Stage Outside the Host Infective Stage Juvenile Steinernema carpocapsae Symbiotic Bacteria Released Bacterial Chamber Mating for Steinernema spp. Two to three generations occur in a single host. About 6 days after the original infection, this is the appearance New Infective Juveniles in 10 Days Entomopathogenic Nematodes Can Control: • Weevils: Diaprepes root weevil, Diaprepes abbreviatus Blue green weevils, Pachnaeus spp. Otiorhynchus spp. Bill bugs • Fungus gnats: e.g., Sciaridae Entomopathogenic Nematodes Can Control: • Scarab larvae: e.g., Japanese beetle, Popillia japonica, Chafers, etc. -

210 Part 319—Foreign Quarantine Notices

§ 318.82–3 7 CFR Ch. III (1–1–03 Edition) The movement of plant pests, means of 319.8–20 Importations by the Department of conveyance, plants, plant products, and Agriculture. other products and articles from Guam 319.8–21 Release of cotton and covers after into or through any other State, Terri- 18 months’ storage. 319.8–22 Ports of entry or export. tory, or District is also regulated by 319.8–23 Treatment. part 330 of this chapter. 319.8–24 Collection and disposal of waste. 319.8–25 Costs and charges. § 318.82–3 Costs. 319.8–26 Material refused entry. All costs incident to the inspection, handling, cleaning, safeguarding, treat- Subpart—Sugarcane ing, or other disposal of products or ar- 319.15 Notice of quarantine. ticles under this subpart, except for the 319.15a Administrative instructions and in- services of an inspector during regu- terpretation relating to entry into Guam larly assigned hours of duty and at the of bagasse and related sugarcane prod- usual places of duty, shall be borne by ucts. the owner. Subpart—Citrus Canker and Other Citrus PART 319—FOREIGN QUARANTINE Diseases NOTICES 319.19 Notice of quarantine. Subpart—Foreign Cotton and Covers Subpart—Corn Diseases QUARANTINE QUARANTINE Sec. 319.24 Notice of quarantine. 319.8 Notice of quarantine. 319.24a Administrative instructions relating 319.8a Administrative instructions relating to entry of corn into Guam. to the entry of cotton and covers into Guam. REGULATIONS GOVERNING ENTRY OF INDIAN CORN OR MAIZE REGULATIONS; GENERAL 319.24–1 Applications for permits for impor- 319.8–1 Definitions. -

Incipient Non-Adaptive Radiation by Founder Effect? Oliarus Polyphemus Fennah, 1973 – a Subterranean Model Case

Incipient non-adaptive radiation by founder effect? Oliarus polyphemus Fennah, 1973 – a subterranean model case. (Hemiptera: Fulgoromorpha: Cixiidae) Dissertation zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades doctor rerum naturalium (Dr. rer. nat.) im Fach Biologie eingereicht an der Mathematisch-Naturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät I der Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin von Diplom-Biologe Andreas Wessel geb. 30.11.1973 in Berlin Präsident der Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin Prof. Dr. Christoph Markschies Dekan der Mathematisch-Naturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät I Prof. Dr. Lutz-Helmut Schön Gutachter/innen: 1. Prof. Dr. Hannelore Hoch 2. Prof. Dr. Dr. h.c. mult. Günter Tembrock 3. Prof. Dr. Kenneth Y. Kaneshiro Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 20. Februar 2009 Incipient non-adaptive radiation by founder effect? Oliarus polyphemus Fennah, 1973 – a subterranean model case. (Hemiptera: Fulgoromorpha: Cixiidae) Doctoral Thesis by Andreas Wessel Humboldt University Berlin 2008 Dedicated to Francis G. Howarth, godfather of Hawai'ian cave ecosystems, and to the late Hampton L. Carson, who inspired modern population thinking. Ua mau ke ea o ka aina i ka pono. Zusammenfassung Die vorliegende Arbeit hat sich zum Ziel gesetzt, den Populationskomplex der hawai’ischen Höhlenzikade Oliarus polyphemus als Modellsystem für das Stu- dium schneller Artenbildungsprozesse zu erschließen. Dazu wurde ein theoretischer Rahmen aus Konzepten und daraus abgeleiteten Hypothesen zur Interpretation be- kannter Fakten und Erhebung neuer Daten entwickelt. Im Laufe der Studie wurde zur Erfassung geografischer Muster ein GIS (Geographical Information System) erstellt, das durch Einbeziehung der historischen Geologie eine präzise zeitliche Einordnung von Prozessen der Habitatsukzession erlaubt. Die Muster der biologi- schen Differenzierung der Populationen wurden durch morphometrische, etho- metrische (bioakustische) und molekulargenetische Methoden erfasst. -

Terrestrial Arthropod Surveys on Pagan Island, Northern Marianas

Terrestrial Arthropod Surveys on Pagan Island, Northern Marianas Neal L. Evenhuis, Lucius G. Eldredge, Keith T. Arakaki, Darcy Oishi, Janis N. Garcia & William P. Haines Pacific Biological Survey, Bishop Museum, Honolulu, Hawaii 96817 Final Report November 2010 Prepared for: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Pacific Islands Fish & Wildlife Office Honolulu, Hawaii Evenhuis et al. — Pagan Island Arthropod Survey 2 BISHOP MUSEUM The State Museum of Natural and Cultural History 1525 Bernice Street Honolulu, Hawai’i 96817–2704, USA Copyright© 2010 Bishop Museum All Rights Reserved Printed in the United States of America Contribution No. 2010-015 to the Pacific Biological Survey Evenhuis et al. — Pagan Island Arthropod Survey 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary ......................................................................................................... 5 Background ..................................................................................................................... 7 General History .............................................................................................................. 10 Previous Expeditions to Pagan Surveying Terrestrial Arthropods ................................ 12 Current Survey and List of Collecting Sites .................................................................. 18 Sampling Methods ......................................................................................................... 25 Survey Results .............................................................................................................. -

List of the Lepidoptera of Black Sturgeon Lake, Northwestern Ontario, and Dates of Adult Occurrence

The Great Lakes Entomologist Volume 24 Number 1 - Spring 1991 Number 1 - Spring 1991 Article 8 March 1991 List of the Lepidoptera of Black Sturgeon Lake, Northwestern Ontario, and Dates of Adult Occurrence C. J. Sanders Forestry Canada Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/tgle Part of the Entomology Commons Recommended Citation Sanders, C. J. 1991. "List of the Lepidoptera of Black Sturgeon Lake, Northwestern Ontario, and Dates of Adult Occurrence," The Great Lakes Entomologist, vol 24 (1) Available at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/tgle/vol24/iss1/8 This Peer-Review Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Biology at ValpoScholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Great Lakes Entomologist by an authorized administrator of ValpoScholar. For more information, please contact a ValpoScholar staff member at [email protected]. Sanders: List of the Lepidoptera of Black Sturgeon Lake, Northwestern Onta 1991 THE GREAT LAKES ENTOMOLOGIST 51 LIST OF THE LEPIDOPTERA OF BLACK STURGEON LAKE, NORTHWESTERN ONTARIO, AND DATES OF ADULT OCCURRENCE C.J. SandersI ABSTRACT From May to September each year from 1960 through 1968, a collection of Lepidoptera was made at Black Sturgeon Lake, northwestern Ontario, from speci mens captured in a light trap and from specimens netted during the day. A total of 564 species was recorded from 70 families. A list of the species with dates of capture is presented. From 1960 through 1968, a 15-watt black-light trap was operated each year at a Forestry Canada field station at Black Sturgeon Lake, northwestern Ontario. -

その他の昆虫類 Other Miscellaneous Insects 高橋和弘 1) Kazuhiro Takahashi

丹沢大山総合調査学術報告書 丹沢大山動植物目録 (2007) その他の昆虫類 Other Miscellaneous Insects 高橋和弘 1) Kazuhiro Takahashi 要 約 今回の目録に示した各目ごとの種数は, 次のとおりである. カマアシムシ目 10 種 ナナフシ目 5 種 ヘビトンボ目 3 種 トビムシ目 19 種 ハサミムシ目 5 種 ラクダムシ目 2 種 イシノミ目 1 種 カマキリ目 3 種 アミメカゲロウ目 55 種 カゲロウ目 61 種 ゴキブリ目 4 種 シリアゲムシ目 13 種 トンボ目 62 種 シロアリ目 1 種 チョウ目 (ガ類) 1756 種 カワゲラ目 52 種 チャタテムシ目 11 種 トビケラ目 110 種 ガロアムシ目 1 種 カメムシ目 (異翅亜目除く) 501 種 バッタ目 113 種 アザミウマ目 19 種 凡 例 清川村丹沢山 (Imadate & Nakamura, 1989) . 1. 本報では、 カゲロウ目を石綿進一、 カワゲラ目を石塚 新、 トビ ミヤマカマアシムシ Yamatentomon fujisanum Imadate ケラ目を野崎隆夫が執筆し、 他の丹沢大山総合調査報告書生 清川村丹沢堂平 (Imadate, 1994) . 物目録の昆虫部門の中で諸般の事情により執筆者がいない分類 群について,既存の文献から,データを引用し、著者がまとめた。 文 献 特に重点的に参照した文献は 『神奈川県昆虫誌』(神奈川昆虫 Imadate, G., 1974. Protura Fauna Japonica. 351pp., Keigaku Publ. 談話会編 , 2004)※である. Co., Tokyo. ※神奈川昆虫談話会編 , 2004. 神奈川県昆虫誌 . 1438pp. 神 Imadate, G., 1993. Contribution towards a revision of the Proturan 奈川昆虫談話会 , 小田原 . Fauna of Japan (VIII) Further collecting records from northern 2. 各分類群の記述は, 各目ごとに分け, 引用文献もその目に関 and eastern Japan. Bulletin of the Department of General するものは, その末尾に示した. Education Tokyo Medical and Dental University, (23): 31-65. 2. 地名については, 原則として引用した文献に記されている地名 Imadate, G., 1994. Contribution towards a revision of the Proturan とした. しがって, 同一地点の地名であっても文献によっては異 Fauna of Japan (IX) Collecting data of acerentomid and なった表現となっている場合があるので, 注意していただきたい. sinentomid species in the Japanese Islands. Bulletin of the Department of General Education Tokyo Medical and Dental カマアシムシ目 Protura University, (24): 45-70. カマアシムシ科 Eosentomidae Imadate, G. & O. Nakamura, 1989. Contribution towards a revision アサヒカマアシムシ Eosentomon asahi Imadate of the Proturan Fauna of Japan (IV) New collecting records 山 北 町 高 松 山 (Imadate, 1974) ; 清 川 村 宮 ヶ 瀬 (Imadate, from the eastern part of Honshu.