VOLUME 3 NUMBER 15 COPIAPOA MONTANA Actual Size

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Haseltonia Articles and Authors.Xlsx

ABCDEFG 1 CSSA "HASELTONIA" ARTICLE TITLES #1 1993–#26 2019 AUTHOR(S) R ISSUE(S) PAGES KEY WORD 1 KEY WORD 2 2 A Cactus Database for the State of Baja California, Mexico Resendiz Ruiz, María Elena 2000 7 97-99 BajaCalifornia Database A First Record of Yucca aloifolia L. (Agavaceae/Asparagaceae) Naturalized Smith, Gideon F, Figueiredo, 3 in South Africa with Notes on its uses and Reproductive Biology Estrela & Crouch, Neil R 2012 17 87-93 Yucca Fotinos, Tonya D, Clase, Teodoro, Veloz, Alberto, Jimenez, Francisco, Griffith, M A Minimally Invasive, Automated Procedure for DNA Extraction from Patrick & Wettberg, Eric JB 4 Epidermal Peels of Succulent Cacti (Cactaceae) von 2016 22 46-47 Cacti DNA 5 A Morphological Phylogeny of the Genus Conophytum N.E.Br. (Aizoaceae) Opel, Matthew R 2005 11 53-77 Conophytum 6 A New Account of Echidnopsis Hook. F. (Asclepiadaceae: Stapeliae) Plowes, Darrel CH 1993 1 65-85 Echidnopsis 7 A New Cholla (Cactaceae) from Baja California, Mexico Rebman, Jon P 1998 6 17-21 Cylindropuntia 8 A New Combination in the genus Agave Etter, Julia & Kristen, Martin 2006 12 70 Agave A New Series of the Genus Opuntia Mill. (Opuntieae, Opuntioideae, Oakley, Luis & Kiesling, 9 Cactaceae) from Austral South America Roberto 2016 22 22-30 Opuntia McCoy, Tom & Newton, 10 A New Shrubby Species of Aloe in the Imatong Mountains, Southern Sudan Leonard E 2014 19 64-65 Aloe 11 A New Species of Aloe on the Ethiopia-Sudan Border Newton, Leonard E 2002 9 14-16 Aloe A new species of Ceropegia sect. -

CCCSS September 2010 Newsletter.Indd

CENTRAL COAST CACTUS AND SUCCULENT SOCIETY NEWSLETTER Pismo Beach,CA93449 780 MercedSt. c/o MarkusMumper & SucculentSociety Central CoastCactus On the Dry Side September 2010 Inside this issue: CCCSS August Meeting Recap •Upcoming Speaker Gene Schroeder greeted about 100 members that showed up for our August meeting. He reminded everyone that our October - Nick Wilkinson meeting would be the 3rd Sunday of the month instead of the •Last Month’s 2nd so mark your calendars for the 17th. Our brag table had some very impressive plants which included a 1st prize “ Best - Meeting Minutes Echeveria” from the Paso Fair submitted by Tim Dawson. He won with his beautiful Echeveria subrigida. Rich Hart also showed us •Genus of the Month his awesome Brunsvigia josephinae. This South African bulb was in - Ferocactus flower that was almost 3 feet tall. He said this plant was 20 years - Adromischus old. He started it from seed and it finally bloomed after 17 years. Our raffle table keeps getting better and thanks to Mary Peracca and Gene Schroeder for donating some of their plants for the raffle table. Our team of Rob Skillen, Charles Spotts and Gene Schroeder all shared their specimens with us for the plants of the month: Thelocactus and Bromeliad. We are so fortunate to have these knowledgeable guys to be a part of our club. Also on that list is Nick Wilkinson who missed the meeting as he was selling at a show. We were honored to have Woody Minnich as our speaker this month from New Mexico. His presentation of Rio Grande Do Sol was informative with wonderful photos and a twist of humor. -

02.2020 Central Spine Final

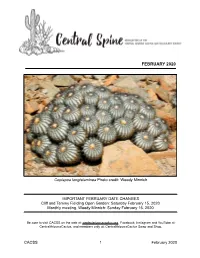

FEBRUARY 2020 Copiapoa longistaminea Photo credit: Woody Minnich IMPORTANT FEBRUARY DATE CHANGES Cliff and Tammy Fielding Open Garden: Saturday February 15, 2020 Monthly meeting, Woody Minnich: Sunday February 16, 2020 Be sure to visit CACSS on the web at: centralarizonacactus.org, Facebook, Instagram and YouTube at: CentralArizonaCactus, and members only at: CentralArizonaCactus Swap and Shop. CACSS 1 February 2020 20 YEARS IN THE ATACAMA, LAND OF THE COPIAPOAS Photos and Text by Wendell S. ‘Woody’ Minnich Similar to the coast of Namibia, the coastal and inland regions of northern Chile, known as the Atacama, are mainly watered by amazing fogs, “the Camanchacas.” These fog- fed regions, in two of the driest deserts in the world, have some of the most interesting cactus and succulents to be found anywhere. The Atacama of northern Chile has an endemic genus considered by many to be one of the most dramatic to have ever evolved-the Copiapoa. This ancient genus is also believed to be tens of thousands of years old, and there are those who feel it might well be on its way out! The ocean currents that affect the coastal Atacama have changed considerably over the last hundreds of years, and now its only source of moisture is primarily from consistent dense fogs. Some of these areas rarely, if ever, get rain, and the plants that have evolved there live almost entirely off the heavy condensation from the Camanchaca. There are many different Copiapoa species ranging from small quarter-sized subterranean geophytes, to giant 1,000-year-old, 300-head mounding clusters. -

CACTUS COURIER Newsletter of the Palomar Cactus and Succulent Society

BULLETIN NOVEMBER 2014 CACTUS COURIER Newsletter of the Palomar Cactus and Succulent Society Volume 60, Number 11 November 2014 The Meeting is the 4th Saturday NOVEMBER 22, 2014 Park Avenue Community Center 210 Park Ave Escondido, CA 92025 Noon!! Coffee!! Photo by Robert Pickett “Ethiopia – Plants, History, and Cultures” • • Gary James • • Gary James has been interested in succulent In recent years he has been traveling to succulent-rich plants for many years – both his grandmother and his parts of the world to observe plants in habitat. Seeing parents had large succulent gardens. Growing up in South them growing in their natural areas gives an observer a Pasadena allowed him to spend many days visiting the better idea of how to care for the plants in one’s Huntington Botanic Gardens – back when admission was collection. free! In 2000 he organized a tour of Ethiopia for a group of friends. They traveled all over the country and observed a number of wonderful plant habitats. Ethiopia is a fascinating country with a long history of having never been colonized by a European power. The country includes many interesting tribes in the Omo River Valley, intriguing monuments in the north, and unusual Christian churches in the Lalibela area. Theirs is a rich Moslem culture as well. The talk will be a general introduction to the variety of cultures, tribes, historic monuments, as well as a look at many of the unusual plants that are found throughout the country. vvvvvvvv Board Meeting • Plant Sales • Brag Plants • Exchange Table REFRESHMENTS Lorie Johansen Martha Hansen • • • YOUR NAME HERE! • • • Please think about bringing something to share – it makes the day more fun! And we have a reputation to uphold!! Plant of the Month • • Tylecodon • • Tylecodon is a genus of succulent plants in the family Crassulaceae. -

Copyright Notice

Copyright Notice This electronic reprint is provided by the author(s) to be consulted by fellow scientists. It is not to be used for any purpose other than private study, scholarship, or research. Further reproduction or distribution of this reprint is restricted by copyright laws. If in doubt about fair use of reprints for research purposes, the user should review the copyright notice contained in the original journal from which this electronic reprint was made. Journal of Vegetation Science 7: 667-680, 1996 © IAVS; Opulus Press Uppsala. Printed in Sweden - Biogeographic patterns of Argentine cacti - 667 Species richness of Argentine cacti: A test of biogeographic hypotheses Mourelle, Cristina & Ezcurra, Exequiel Centro de Ecología, UNAM, Apartado Postal 70-275, 04510 - Mexico, D.F., Mexico; Fax +52 5 6228995; E-mail [email protected] Abstract. Patterns of species richness are described for 50 cacti and (e) pereskioid cacti. Columnar species have columnar, 109 globose and 50 opuntioid cacti species in 318 column-like stems with ribs, formed by an arrangement grid cells (1°×1°) covering Argentina. Biological richness of the areoles in longitudinal rows. These species have hypotheses were tested by regressing 15 environmental parallel vascular bundles, separated by succulent paren- descriptors against species richness in each group. We also chyma, sometimes fusing towards a woody base in the included the collection effort (estimated as the logarithm of the number of herbarium specimens collected in each cell) to adults. We broadly considered as columnar cacti: estimate the possible error induced by underrepresentation in candelabriform arborescent species, unbranched erect certain cells. -

Die Gattung Frailea (Br. & R.) Prestlé

Die Gattung Frailea (Br. & R.) Prestlé K.H. Prestlé 3. Ausgabe - 1998 Die Gattung Frailea Br. & R. by K.H. Prestlé 1 Die Gattung Frailea (Br. & R.) Prestlé K.H. Prestlé 3. Ausgabe - 1998 Die Gattung Frailea Br. & R. by K.H. Prestlé 2 Einleitung Nachdem die provisorische Ausgabe aus dem Jahre 1991 nicht mehr aktuell ist und die zweiteAusgabe vergriffen, halte ich es für nötig, eine dritte erweiterte Bearbeitung der Gattung Frailea heraus zu bringen, da die Nachfrage zugenommen hat. Das Ziel die Gattung in seiner Gesamtheit zu erforschen, ist zwar noch immer nicht erreicht, doch haben wir im Laufe der vergangenen Jahre viele neue Erkenntnisse durch weitere Reisen und Forschungen in den Heimatländern der Fraileen hinzu bekommen, so dass nur eine Neubearbeitung der Gattung den Wissenstand von 1998 dokumentieren kann. Ich möchte mich hier bei meinen Freunden und Mitarbeitern bedanken, die viel Zeit und Energie in der Bearbeitung der lat. Übersetzungen und der Herstellung vieler REM-Photo's eingesetzt haben, ohne die eine derartig grosse Arbeit garnicht möglich geworden wäre. Dank gilt auch meinen brasil. Freunden und Reisebegleitern, die mich über 30 000 km auf meinen 7 Studienreisen begleitet haben, sowie den Freunden, die auf ihren Reisen durch Argentinien, Paraguay und Ostbolivien, das Wissen über die Gattung Frailea durch eigene Funde bereichern konnten. Ich hoffe, dass diese Ausgabe, welche auch als Arbeitsgrundlage gedacht ist, dazu beitragen wird, dass die vielen Formen der Gattung Frailea bei den Liebhabern immer mehr Zuspruch finden werden und das die Ausgabe dazu beitragen wird, dass das Wissen über die Fraileen auch in Zukunft erhalten bleibt. -

On the Dry Side 2018

APRIL 2018 On the Dry Side Newsletter of the Monterey Bay Area Cactus & Succulent Society Contents Presidents Message Contents .......................................... 1 We are now into the season of spring, when plants –and weeds– President’s Message ........................ 1 grow vigorously and the weather inspires our gardening urges. MBACSS Board Minutes ................. 2 The schedule for our Spring Show & Sale was earlier than usual MBACSS Spring Sale – Pix .............. 3 this year, but the timing apparently was right relative to seasonal April Program ................................. 5 interest in new plants: the turnout was good, and sales seemed MBACSS Calendar 2018 ................. 6 satisfying to our many customers and rewarding for MBACSS’s Additional Resources ....................... 7 propagating members. We’ll learn more about the results as the April Mini-Show Plants ................... 8 financial dust settles. March Mini-Show Winners ............. 9 Many thanks to vendors and other members who supported the Officers & Chairpersons ................... 10 success of this event. We will thank each one during our meeting, What Are They Thinking? ............... 10 but we appreciate in particular Naomi Bloss, Gary Stubblefield and Sarah Martin. Our speaker for the April meeting, Ernesto Sandoval, has a timely topic for this spring season: “Succulent Propagation from Seeds” will provide technical information and horticultural inspiration for members who are already engaged in seed propagation, or would be interested in giving a try to real gardening. Left: Customers at the Spring Show & Sale examining a possible new addition to their garden. Photo by Paul Albert. Save the Date! MBACSS Meets Board Meets Future Meetings April 15, 2018 April 15, 2018 Third Sundays Veterans of Foreign Potluck @ 12:30 Board @ 11:00 Wars, Post 1716 Gathering @ 12:00 Members always 1960 Freedom Blvd. -

Species Classification and Nomenclature by Norbert Leist and Andrea Jonitz Prof

ISTA Purity Seminar 15. June 2009 Zürich TlTools for seed identifi cati on species classification and nomenclature by Norbert Leist and Andrea Jonitz Prof. Dr. Norbert Leist Dr. Andrea Jonitz Brahmsstr.25 LTZ Augustenberg 76669 Bad Schönborn Neßlerstr.23 Germany 76227 Karlsruhe [email protected] Germany [email protected] Aquilegia vulgaris, Variation Variation • Variation is everywhere in biological systems. Natural variation at the population level is usualy not continuous, but occurs in discrete units or taxa. Easily the most important taxonomic level is the species because it is often the smallest clearly recognizable and discrete set of populations. • Understanding how species form and how to recognize them have been major challenges to systematists. The variation in one population becomes interrupted, the way to a split into two species strong hairy nearly glabrous Variation on species • Sources of variation: MttiMutation Recombination Independent assortment of the chromosomes Random genetic drift Selection Conservation of species characteristics avoiding gene flow Isolating barriers: temporal (seasonal, diurnal) habitat (wet, dry; calceous, silicious) floral (structural, behavioral eg. adaptations for pollinators) reproductive mode (self fertilisation, agamospery) incompatibility (pollen, seeds) hybrid inviability hybrid floral isolation hybrid sterility hybrid break down Iris germanica Iris sibirica Isolation by habitat Definition of „species“ is not easy A species is the smallest aggregation of populations -

South American Cacti in Time and Space: Studies on the Diversification of the Tribe Cereeae, with Particular Focus on Subtribe Trichocereinae (Cactaceae)

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2013 South American Cacti in time and space: studies on the diversification of the tribe Cereeae, with particular focus on subtribe Trichocereinae (Cactaceae) Lendel, Anita Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich ZORA URL: https://doi.org/10.5167/uzh-93287 Dissertation Published Version Originally published at: Lendel, Anita. South American Cacti in time and space: studies on the diversification of the tribe Cereeae, with particular focus on subtribe Trichocereinae (Cactaceae). 2013, University of Zurich, Faculty of Science. South American Cacti in Time and Space: Studies on the Diversification of the Tribe Cereeae, with Particular Focus on Subtribe Trichocereinae (Cactaceae) _________________________________________________________________________________ Dissertation zur Erlangung der naturwissenschaftlichen Doktorwürde (Dr.sc.nat.) vorgelegt der Mathematisch-naturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Universität Zürich von Anita Lendel aus Kroatien Promotionskomitee: Prof. Dr. H. Peter Linder (Vorsitz) PD. Dr. Reto Nyffeler Prof. Dr. Elena Conti Zürich, 2013 Table of Contents Acknowledgments 1 Introduction 3 Chapter 1. Phylogenetics and taxonomy of the tribe Cereeae s.l., with particular focus 15 on the subtribe Trichocereinae (Cactaceae – Cactoideae) Chapter 2. Floral evolution in the South American tribe Cereeae s.l. (Cactaceae: 53 Cactoideae): Pollination syndromes in a comparative phylogenetic context Chapter 3. Contemporaneous and recent radiations of the world’s major succulent 86 plant lineages Chapter 4. Tackling the molecular dating paradox: underestimated pitfalls and best 121 strategies when fossils are scarce Outlook and Future Research 207 Curriculum Vitae 209 Summary 211 Zusammenfassung 213 Acknowledgments I really believe that no one can go through the process of doing a PhD and come out without being changed at a very profound level. -

Taxonomic Notes on Amaurobius (Araneae: Amaurobiidae), Including the Description of a New Species

Zootaxa 4718 (1): 047–056 ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) https://www.mapress.com/j/zt/ Article ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2020 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.4718.1.3 http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:5F484F4E-28C2-44E4-B646-58CBF375C4C9 Taxonomic notes on Amaurobius (Araneae: Amaurobiidae), including the description of a new species YURI M. MARUSIK1,2, S. OTTO3 & G. JAPOSHVILI4,5 1Institute for Biological Problems of the North RAS, Portovaya Str. 18, Magadan, Russia. E-mail: [email protected] 2Department of Zoology & Entomology, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein 9300, South Africa 3GutsMuthsstr. 42, 04177 Leipzig, Germany. 4Institute of Entomology, Agricultural University of Georgia, Agmashenebeli Alley 13 km, 0159 Tbilisi, Georgia 5Invertebrate Research Center, Tetrtsklebi, Telavi municipality 2200, Georgia 6Corresponding author. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract A new species, Amaurobius caucasicus sp. n., is described based on the holotype male and two male paratypes from Eastern Georgia. A similar species, A. hercegovinensis Kulczyński, 1915, known only from the original description is redescribed. The taxonomic status of Amaurobius species considered as nomina dubia and species described outside the Holarctic are also assessed. Amaurobius koponeni Marusik, Ballarin & Omelko, 2012, syn. n. described from northern India is a junior synonym of A. jugorum L. Koch, 1868 and Amaurobius yanoianus Nakatsudi, 1943, syn. n. described from Micronesia is synonymised with the titanoecid species Pandava laminata (Thorell, 1878) a species known from Eastern Africa to Polynesia. Considerable size variation in A. antipovae Marusik et Kovblyuk, 2004 is briefly discussed. Key words: Aranei, Asia, Caucasus, Georgia, Kakheti, misplaced, new synonym, nomen dubium, redescription Introduction Amaurobius C.L. -

Phylogenetic Relationships in the Cactus Family (Cactaceae) Based on Evidence from Trnk/Matk and Trnl-Trnf Sequences

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: http://www.researchgate.net/publication/51215925 Phylogenetic relationships in the cactus family (Cactaceae) based on evidence from trnK/matK and trnL-trnF sequences ARTICLE in AMERICAN JOURNAL OF BOTANY · FEBRUARY 2002 Impact Factor: 2.46 · DOI: 10.3732/ajb.89.2.312 · Source: PubMed CITATIONS DOWNLOADS VIEWS 115 180 188 1 AUTHOR: Reto Nyffeler University of Zurich 31 PUBLICATIONS 712 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Available from: Reto Nyffeler Retrieved on: 15 September 2015 American Journal of Botany 89(2): 312±326. 2002. PHYLOGENETIC RELATIONSHIPS IN THE CACTUS FAMILY (CACTACEAE) BASED ON EVIDENCE FROM TRNK/ MATK AND TRNL-TRNF SEQUENCES1 RETO NYFFELER2 Department of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology, Harvard University Herbaria, 22 Divinity Avenue, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02138 USA Cacti are a large and diverse group of stem succulents predominantly occurring in warm and arid North and South America. Chloroplast DNA sequences of the trnK intron, including the matK gene, were sequenced for 70 ingroup taxa and two outgroups from the Portulacaceae. In order to improve resolution in three major groups of Cactoideae, trnL-trnF sequences from members of these clades were added to a combined analysis. The three exemplars of Pereskia did not form a monophyletic group but a basal grade. The well-supported subfamilies Cactoideae and Opuntioideae and the genus Maihuenia formed a weakly supported clade sister to Pereskia. The parsimony analysis supported a sister group relationship of Maihuenia and Opuntioideae, although the likelihood analysis did not. Blossfeldia, a monotypic genus of morphologically modi®ed and ecologically specialized cacti, was identi®ed as the sister group to all other Cactoideae. -

30Th Annual Inter-City Cactus and Succulent Show

30th Annual Inter-City Cactus and Succulent Show T Glavich Agave utahensis v eborispina 9 - 5 August 8 - 9 2015 Los Angeles County Arboretum 301 N Baldwin Ave Arcadia Horticultural Classifications Competitive entries shall be as follows: NOVICE Exhibitor has won no more than 40 blue ribbons total in recognized CSS shows. ADVANCED Exhibitor has won 41 or more blue ribbons. No Commercial sellers. OPEN Exhibitor must have won 80 or more blue ribbons or be a commercial seller of Cacti or Succulents Set-up Times Wed. 5th 1:00 to 7:00 p.m., Thurs. 6th, 8:00 am to 9:00 p.m. and Fri. 7th 9:00 to 5:00 p.m. The sales area will be open for pre-sale at 2:00 p.m. Fri. the 8th for workers and participants. Plants from pre- sale must be paid for and removed from the show not later than 7:00 p.m. Fri. 7th or they will be placed back in the sales area. All entrants must register their total entries in the show registrar prior to placement on tables. Judging will begin at 5 p.m. on Friday the 7th Take-out Time is Sunday the 9th from 5:00 p.m. All Plants must be removed Sunday Evening Judging Scale Condition of plant - 60 points Size and degree of Maturity - 15 points Staging and presentation - 20 points Nomenclature - 5 points Arrangements and Displays will be at the Judges option. Points awarded towards trophies; First = 6 points, Second = 3 points, Third = 1 point Special Ribbons will be used as tie breakers Show Rules • The Inter-City Show is open to anyone wishing to enter.