The San Diego Burrito: Authenticity, Place, and Cultural Interchange

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chimichanga Carne Asada Pollo Salad Fajita Texana Appetizers Chicken Wings Cheese Dip – 3.25 Chicken Wings Served with Celery and Ranch Dressing

Chimichanga Carne Asada Pollo Salad Fajita Texana Appetizers Chicken Wings Cheese Dip – 3.25 Chicken Wings Served with celery and ranch dressing. Bean Dip Choice of plain, hot and BBQ. Refried beans smothered with (10) – 8.50 our cheese sauce – 3.75 Jalisco Sampler Chorizo Dip Beef taquitos, grilled chicken Mexican sausage smothered with quesadillas and 4 wings – 8.75 our cheese sauce – 4.25 Triangle Quesadillas Guacamole Dip – 3.25 Grilled chicken or steak quesadilla Chunky Guacamole Dip with guacamole, pico de gallo, sour Our chunky guacamole made with diced cream and lettuce – 7.00 avocado, onions, tomatoes and cilantro – 4.50 Jalisco’s Spinach Dip Loaded Cheese Fries Chopped baby spinach smothered French fries covered with Monterey cheese, with our cheese sauce – 4.50 cheddar cheese and our own cheese Jalisco Dip sauce, bacon bits and jalapeños – 5.50 Triangle Quesadillas Ground beef smothered in cheese sauce – 3.50 Jalapeño Poppers (6) Pico de Gallo Filled with cream cheese – 4.55 Tomatoes, onions and cilantro mixed Mozzarella Sticks (6) – 4.55 together with squeezed lime juice and a pinch of salt – 1.75 Nachos Served anytime. All nachos include cheese. Fajita Nachos Nachos with Beef & Beans – 6.25 Nachos topped with chicken or steak strips cooked with grilled onions and bell peppers – 8.75 Nachos con Pollo Nachos with chicken and melted cheese – 6.25 Nachos Supreme Nachos topped with beef or chicken, lettuce, Fiesta tomato, sour cream and grated cheese – 6.75 Nachos topped with chicken, cheese, ground beef, beans, lettuce, guacamole, -

Chicken POLLO Vegetarian 999 Chimichangas

chicken POLLO | CHIMICHANGAS | CHICKEN STEAKS | VEGETARIAN | SPECIALTIES All dishes come with tortillas POLLO FAVORITO POLLO AZADO Grilled chicken breast with tropical Grilled chicken breast served with vegetables and a salad 12.99 a salad and avocado 12.50 POLLO FUNDIDO ARROZ CON POLLO Shredded chicken over rice with chorizo Chicken strips over a bed of rice, covered in our and cheese. Served with tortillas 12.99 cheese sauce and served with tortillas 13.99 POLLO LOCO ARROZ CON POLLO Y CAMARONES Grilled chicken breast with shrimp and Chicken strips and shrimp tossed with onion. Served with a salad and rice 14.50 cheese dip. Served with Mexican rice 14.50 HOT & SPICY CHICKEN NEW! POLLO JALISCO Chicken strips in a spicy Diabla sauce with Grilled chicken strips with mushrooms and spinach. onion. Served with rice and beans 13.50 Served with rice, beans, cheese and tortillas 13.50 POLLO TROPICAL NEW! POLLO CHIPOTLE Chicken breast with a tropical veggie mix Grilled chicken strips covered in our delicious chipotle and pineapple. Served with rice 13.50 sauce. Served with rice, beans and tortillas 13.50 NEW! POLLO HAWAIIANO NEW! ARROZ CON POLLO AND VEGGIES Grilled chicken breast cooked with onions, ham Grilled chicken strips and California veggies. Topped and pineapple, then topped with cheese. Served with cheese dip, Served on a bed of rice 12.99 with rice, beans and flour tortillas 13.50 NEW! POLLO MONTERREY Grilled chicken breast, onions, mushrooms, tomatoes and peppers, topped with cheese. Served with rice and beans 13.50 NEW! POLLO TOLUCA Grilled chicken breast with chorizo and cheese. -

Download PDF Menu

3550 LONG BEACH BLVD. 16601 S. WESTERN AVE. 2104 PACIFIC COAST HIGHWAY 57 E. HOLLY ST. LONG BEACH, CA 90807 GARDENA, CA 90247 LOMITA, CA 90717 PASADENA, CA. 91103 562-490-0700 310-329-7266 424-328-0080 626-469-0099 Breakfast SERVED ALL DAY! THE LUMBERJACK THE CLASSIC Two bacon, two sausage, two eggs any style, BREAKFAST BURRITO house potatoes served with two buttermilk Eggs, bacon, sausage, house potatoes, SHORT RIB BENEDICT pancakes - 13 Upgrade to Specialty Pancakes grilled peppers, onions, jack and Two corncakes topped with short rib braised or plain waffle - 2.00 cheddar cheese served in a flour tortilla - 8.75 barbacoa over mexican street cream corn, poached eggs, and a poblano cream sauce - 16.75 THE "ORIGINAL" LOADED THE SOUTHERN HASH BROWNS Two buttermilk biscuits topped with BUTTERMILK FRIED CHICKEN Two eggs any style, bacon, sausage, sausage country gravy served with two eggs Corn cake topped with a buttermilk fried chicken green onions, jack and cheddar cheese any style, two bacon or sausage, and house breast, sautéed spinach, two eggs any style over hash browns topped with chili aioli potatoes - 12 and a roasted red pepper cream gravy - 16.50 and choice of toast - 13 CHICKEN N’ WAFFLES PITAS CHILAQUILES TWO EGG BREAKFAST Buttermilk fried chicken breast with waffle, Fried corn tortillas mixed with red sauce, or green Two eggs any style, choice of meat: bacon, blackberry butter, blackberry syrup sauce, topped with Jack cheese, sour cream and sausage, keilbasa or ham, served with our house and powdered sugar - 14 green onions. Served with two eggs any style potatoes and choice of toast - 10.50 and a side of rice and refried beans - 14 THE BREAKFAST BURGER Add Carne Asada, Chicken or Chorizo - 2.00 THE PAN FRENCH TOAST The all-beef burger (or turkey) with Add Chili Verde - 3.00 Two batter dipped brioche slices with vanilla cheddar cheese, two strips of bacon, butter and powdered sugar. -

Los Cazadores

eatBasalt.com Los Cazadores APPETIZERS * * THESE ITEMS MAY BE SERVED RAW OR Ostiones (Oysters) $19.99 UNDERCOOKED, OR CONTAIN RAW OR Rellenos/Stuffed: Ceviche de Camaron/Shrimp UNDERCOOKED INGREDIENTS. Ceviche- $24.99 CONSUMING RAW OR UNDERCOOKED — Media Dozena/ Half a Dozen- $10.99 MEATS, POULTRY, SEAFOOD, SHELLFISH, Rellena/Stuffed- $13.99 OR EGGS MAY INCREASE YOUR RISK OF Queso Fundido FOODBORNE ILLNESS. — With Shrimp- $7.49 With Chorizo- * Tostada de Ceviche de $7.49 $6.99 Camaron/Shrimp Shrimp cooked in lime juice, onion, tomatoes, Chips and Guacamole $7.28 cucumber and cilantro Chips and Salsa $3.39 — Add Octopus/ Mas Pulpo $8.49 The first basket will be free. * Copa de Ceviche de $15.79 Camaron Acompañada con Chips o Tostadas — With Chips or Tostadas A* Copa de Ceviche Culichi $17.99 BOTANAS Shrimp ceviche, boiled shrimp, octopus, oysters ¹ Botana Huichol $19.99 and fish. Shrimp with shell cooked in huichol sauce — With Chips or Tostadas served with shrimp ceviche and 2 oysters Hot Wings $12.99 ¹ Botana Jalisco $19.99 Una orden de 8 piesas Order of 8 pieces Shrimp with shell cooked in special macho sauce — Sauces: Red Hot (Buffalo) or Spicy BBQ with onions served with shrimp ceviche and 2 Nachitos $9.25 oysters Homemade chips, pulled chicken, cheddar Botana Chipotle $19.99 cheese, sour cream, onions, tomato, cilantro, Shrimp with shell cooked in special chipotle lettuce, avocado, and jalapeños. sauce served with shrimp ceviche and 2 oysters Calamari Frito $13.25 Botana Guajillo $19.99 Side of special mild marinara sauce and sriracha Shrimp with shell cooked in special guajillo mayo sauce with onions served with shrimp ceviche * Aguachile $15.89 and 2 oysters. -

One Night Taco Stand Menu.Pdf

SPECIALTY APPETIZERS TACOS Fiery Fish Taco $3.99 One Night bean dip $8.99 Red cabbage, onion, lime habanero and an avocado slice Black beans, cheese, pico de gallo, avocado, fresh jalapenos and chorizo. topped with siracha sauce. Nachos Supreme $9.99 Pescado (fish) $3.99 A plate of chips covered with melted cheese, ground beef, lettuce, sour Made with a soft flour tortilla, cabbage,pico de gallo, and cream, pico de gallo, guacamole, and jalapeño. Substitute steak or shrimp special sauce. for an additional $3.00. Taco Fresco $3.99 Carne Asada Fries $10.99 Skirt steak topped with fresh lime pico de gallo and queso Fries topped with carne asada, queso, fresh lime pico de gallo. sour cream, fresco. and guacamole. Camaron (shrimp) $3.99 Fajita Nachos $11.99 Made with a soft flour tortilla, cabbage, pico de gallo, and Chicken breast, shrimp, and tender sliced steak grilled with onions, bell special sauce. peppers, and tomatoes. Served on top of a bed of chips and smothered with Ceviche Taco $3.99 cheese. Ceviche and avocado. Queso Dip lg$5.99 Surf & Turf Taco $4.25 Skirt steak and shrimp topped with avocado and drizzled lg Guacamole Dip $7.49 with sriracha ranch. Avocado, tomatoes, onions, cilantro, jalapeño, and lime juice. Sriracha shrimp Taco $3.99 Queso Fundido $7.99 Deep fried southern jumbo shrimp, tossed in our sriracha Cheese dip with chorizo. buffalo sauce, and topped with cabbage. Shrimp Ceviche $9.99 Mr. Potato Taco $3.99 Chorizo, potatoes, and scrambled egg, topped with pico Mexican Esquites $4.99 de gallo and queso fresco. -

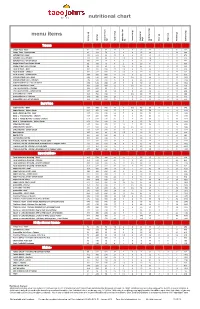

Nutritional Chart Menu Items

nutritional chart menu items Serving (g) Serving Calories from Calories Fat (g) Fat Total Fat Saturated (g) (g) Fat Trans Cholesterol (mg) Carbohydrates (g) (g) Fiber (g) Sugar (g) Protein (mg) Sodium Tacos Crispy Taco –Beef 92 170 90 10 4 0 25 11 2 1 9 290 Crispy Taco –Sirloin Steak 92 160 70 8 3 0 25 10 1 1 10 300 Softshell Taco-Beef 113 210 90 10 4 0 25 21 3 1 11 470 Softshell Taco-Chicken 113 180 50 5 2.5 0 30 20 3 2 13 520 Softshell Taco –Sirloin Steak 113 200 70 8 3 0 25 20 2 1 13 480 Single Street Taco-Sirloin Steak 92 180 70 8 2 0 20 17 1 1 9 360 Single Street Taco-Chicken 92 170 60 6 1.5 0 25 17 1 2 10 380 Taco Bravo® - Beef 184 320 110 13 4.5 0 25 36 7 2 14 640 Taco Bravo® - Chicken 184 320 100 11 3.5 0 40 35 0 3 18 750 Taco Bravo® - Sirloin Steak 184 300 100 11 3.5 0 25 35 0 2 16 650 Stuffed Grilled Taco –Beef 210 540 220 25 9 0.5 45 60 5 3 19 1040 Stuffed Grilled Taco – Chicken 210 530 220 25 9 0 65 54 4 4 22 1150 Stuffed Grilled Taco –Sirloin Steak 210 530 200 23 8 0 50 59 4 3 20 1050 The Taco Perfecto – Beef 137 230 110 12 6 0.5 35 17 3 1 13 450 The Taco Perfecto – Chicken 130 230 90 9 4 0 55 16 1 2 18 520 The Taco Perfecto – Sirloin Steak 137 220 90 10 4 0 40 16 2 1 15 460 Quesadilla Taco –Beef 148 360 150 17 7 0.5 40 33 0 2 15 700 Quesadilla Taco –Chicken 148 390 180 20 7 0 55 33 2 3 17 740 Quesadilla Taco –Sirloin Steak 148 350 140 16 7 0 45 33 2 2 17 750 Burritos Super Burrito –Beef 251 440 160 18 8 0.5 40 51 7 4 19 940 Super Burrito –Sirloin Steak 265 450 160 17 7 0 50 50 6 4 23 1010 Meat & Potato Burrito –Beef 237 -

Download Menu

TACOS Sour Cream ½ pint --- $2.39 Guacamole ½ pint --- MARKET 3 Rolled tacos & cheese --- $3.49 PRICE Shredded beef rolled tacos, topped w/cheddar & jack cheese. Tamales per Dozen --- $16.00 3 Rolled tacos & guacamole -- $4.79 ½ Dozen Tamales --- $9.00 Shredded beef rolled tacos, topped w/guacamole, cheddar & jack cheese. EXTRAS Taco salad --- $4.99 MENU Tortilla shell w/bed of lettuce, beans, Cheese --- 89¢ pico de gallo, your choice of red chilli chicken or shredded beef, topped Guacamole --- 89¢ w/cheddar & sour cream. Sour Cream --- 89¢ BREAKFAST BURRITO $5.39 ea ENCHILADAS Tortilla --- 89¢ A- Bean, Cheese & Eggs. $4.99 Beef --- $5.99 Shredded beef wrapped w/ two corn DESSERTS B- Bacon, Cheese, Potatoes & Eggs. tortillas, topped w/enchiladas sauce, C- Chorizo, Potatoes, Cheese & Eggs. cheddar, jack cheese & lettuce. Churros --- $2.09 Plain, Cajeta, Cream. D- Ham, Potatoes, Cheese & Eggs. Chicken --- $5.99 E- Sausage, Potatoes, Cheese & Eggs. Red chilli chicken wrapped w/ two Churros --- $2.19 F- Mexican omelet ham, Cheese, Salsa & Eggs. corn tortillas, topped w/enchiladas Strawberry. sauce, cheddar, jack cheese & lettuce. G- Machaca, Cheese, Potatoes & Eggs. Xangos --- $4.69 H- Steak, Cheese, Potatoes, Salsa & Eggs. Cheese --- $5.99 Cheese cake chimichanga dessert. Plenty of cheese w/two corn tortillas, I- Potatoes, Cheese & Eggs. $4.99 topped w/enchiladas sauce, cheddar, jack cheese & lettuce. KIDS COMBOS Viva Burrito Colorado KIDS 1 6990 Leetsdale Dr. 7550 Pecos St. 6796 W. Colfax Ave. 5165 Federal Blvd. SIDE ORDERS Denver, CO. 80224 Denver, CO. 80221 Lakewood, CO. 80214 Denver, CO. 80221 One Quesadilla --- $3.99 (303) 320 4753 (303) 412 7391 (303) 274 0754 (303) 455 1384 Quesadillas --- $4.59 OPEN 24HRS Sun-Thu 6am-10pm Every day 6am-10pm Every day 6am-10pm Your choice of Carne Asada or Pollo Fri & Sat 6am-2pm Tortilla filled w/ Cheddar cheese. -

Adobo Rubbed Trout

ADOBO-RUBBED TROUT by Chefs Gustavo Vega & Rachada Prayong-Russell ADOBO | TROUT | PEACH SALAD Trucha Adobada en Hoja de Platano Adobo-Rubbed Trout in Banana Leaves THE ADOBO INGREDIENTS 6 dried guajillo chiles, stemmed and seeded 1 habanero chile 6 cloves of garlic, peeled ¼ cup distilled white vinegar 3 tablespoons achiote paste ¼ cup neutral flavored oil (canola, rice bran, grapeseed) ADOBO-RUBBED TROUT by Chefs Gustavo Vega & Rachada Prayong-Russell ADOBO | TROUT | PEACH SALAD Trucha Adobada en Hoja de Platano Adobo-Rubbed Trout in Banana Leaves THE TROUT INGREDIENTS 1 tablespoon kosher salt 1 tablespoon sugar (6) 6oz pieces of trout, skin removed (can substitute any available white fish) (6) 6 inch squares of banana leaf (from 1 – 2 large banana leaves) (can substitute parchment paper) Preheat oven to 400 ADOBO-RUBBED TROUT by Chefs Gustavo Vega & Rachada Prayong-Russell ADOBO | TROUT | PEACH SALAD Trucha Adobada en Hoja de Platano Adobo-Rubbed Trout in Banana Leaves THE PEACH SALAD INGREDIENTS 3 large ripe peaches 1 tbsp neutral flavored oil (canola, rice bran, grapeseed) 2 tsp freshly squeezed lime juice kosher salt ¼ medium red onion, thinly sliced leaves from ¼ bunch of cilantro Get Ready to Cook! EQUIPMENT LIST 1 QT SAUCE POT BLENDER 10” SAUTÉ PAN ½ SHEET TRAY (18 IN × 13 IN) GRILL PAN (IF AVAILABLE) CUTTING BOARD MIXING BOWLS SHARP KNIFE & SPATULAS MEASURING SPOONS KITCHEN TOWELS AND CUPS ADOBO-RUBBED TROUT by Chefs Gustavo Vega & Rachada Prayong-Russell THE INSTRUCTIONS 1. Prepare the ADOBO: in a medium heatproof bowl, cover the guajillo chiles with boiling water; let sit until soft, about 20 minutes. -

Appetizers Burritos Enchiladas Salads Tacos

Appetizers Enchiladas Tacos Served with Rice and Beans Al Carbon Chicken Taco ....................... $4.95 Pueblo Nachos .......................................... $9.50 Yellow Corn Chips, Jack & Cheddar Cheese, Whole Beans Enchilada Traditional ........................... $11.95 Grilled Chicken, Onions & Cilantro on Soft Corn Tortillas Topped with Guacamole, Sour Cream and Pico de Gallo Choice of Grilled Chicken or Steak* Topped with Red or Al Carbon Steak Taco ............................ $5.50 Chicken ........................................................ $10.95 Green Sauce (“Christmas” is both) and Baked Cheese Grilled Steak, Onions & Cilantro on Soft Corn Tortillas Steak .............................................................. $11.95 *Steak………………………………………......……$12.95 Taco Adobada ........................................... $5.50 Cheese Quesadilla ................................. $8.95 Cheese Enchilada .................................... $10.95 Spicy Slow-cooked Pork Topped with Queso Seco, Onions Add Chicken…$9.95 Add Steak…$10.95 Carne Adobada Enchilada .................. $12.95 and Cilantro on Soft Corn Tortillas Del Mar Fish Taco Quesadilla Poblano ................................ $9.95 Slow Cooked Pork in Red Chiles, Topped with Red or ................................... $5.50 Monterey Jack, Roasted Poblano Chiles, w/ Salsa Romesco Green Sauce (“Christmas” is both) and Baked Cheese Grilled White Fish with our Southwest Slaw on Soft Corn Add Chicken .................................................. $10.95 Hopi Blue -

Appetizers Large Crispy Flour Tor �Lla; Rice & Black Bean S

Santa Fe Burrito 9.50 12.00 Chimichangas Tacos Grilled chicken, roasted corn, potatoes & cheese. Appetizers Large crispy flour tor �lla; rice & black bean s. Add Cheese +.99 Flour tor �llas. Topped with le �uce, sour cream & red salsa. Dinner: Served with a side of rice. So � OR crunchy (corn tor �llas only). Beef Empanadas (3) served with salsa verde 8.99 Steak & Chicken Burrito 10.50 13.75 Lunch Dinner Grilled chicken, steak & cheese. Homemade Chips & Chunky Guacamole 8.50 Beef Chimichanga 10.50 13.00 Seasoned ground beef. Topped with salsa, Nachos 7.50 10.00 13.00 guacamole sauce & sour cream. Homemade corn chips topped with nacho cheese, Steak Burrito Shrimp 3.50 jalapeños, shredded le �uce, pico de gallo, sour cream Steak, onions, tomatoes & cheese. & red salsa. Shrimp marinated in lime juice, topped with sliced Add beef or chicken +1.50 Add Al Pastor or steak+1.99 Chicken Chimichanga 10.50 13.00 avocados & pico de gallo. Beef or Chicken Burrito 9.50 12.00 Shredded chicken. Topped with salsa, guacamole sauce Nachos del Norte 12.00 Ground beef or grilled chicken & cheese. & sour cream. Chips topped with queso blanco, shredded barbacoa, Chicken 3.00 black beans, pickled jalapeños, pico de gallo & roasted Diced chicken cooked with taco seasoning. Topped with Fiesta Chimichanga 11.00 13.50 cheese. poblano peppers. Hamburguesas Ground beef or shredded chicken. Topped with salsa, 7.99 Tostadas Fresh beef pa �es made to order comes with le �uce, tomatoes, guacamole sauce, sour cream & chunky mango salsa. Two tostadas with your choice of beef or onions & served with french fries. -

Starters Burritos & Bowls Taco Fixes

TACO FIXES Sir’s famous grande tacos built on flour or corn (GF) tortillas or lo-carb lettuce wraps (GF) 9.95* +2.95* tacos served with sv rice & choice of frijoles or hand cut fries (GF) * All recipes are gluten free except for cerveza fish & flour tortillas. Shrimp or Beef add $.95 per taco Carne Asada† marinated steak · queso casero · chopped onion & cilantro Grilled Chicken all natural chicken · baja sauce · cilantro · queso casero · pico salsa Diablo Shrimp sriracha & agave glazed shrimp · avocado · green onion · casero · sesame · cabbage STARTERS Nana’s Beef braised shredded beef · grilled peppers, onions & poblanos · queso casero · chipotle crema table’s 1st round of chips & sv salsa Carnitas Adobada slow cooked pork · chile adobo marinade · onion & cilantro · queso casero are on us, extras just a buck!‡ Nana’s Chicken braised shredded chicken · grilled peppers & onions · queso casero · jalapeño salsa (GF) THE Guacamole Fix 9.95 Chopper Shrimp grilled shrimp · applewood bacon · queso casero · pico salsa · chipotle crema prepared tableside · fresh avocado · cilantro sea salt · jalapeño · tomato · lime · queso casero Car Club Chicken avocado · applewood bacon · queso casero · chipotle crema (GF) Rocket Edamame 5.95 Fish Taco Fix– Grilled or Cerveza white fish · casero · cilantro · baja sauce · slaw · lime · pico salsa H grilled edamame · thai chile & ginger salsita glaze NirVana crispy avocado (GF) · grilled peppers & onions · calabazas · mushroom · corn · casero · cilantro (vegan avail) cilantro · pickled red onion · sesame · chile -

BURRITOS 3 ROLLED W/Guacamole, & Cheese

ORDER ONLINE:SENORTACOEXPRESS.COM HARD SHELL TACOS DAILY SPECIALS Big Size Corn Tortilla #1 3 ROLLED TACOS w/Guacamole, Beef Taco & Cheese BURRITOS 3 ROLLED w/Guacamole, & Cheese .............................................4.49 Quesadilla ...........................................................................10.99 Whole Wheat Tortilla add .25 5 ROLLED w/Guacamole, Lettuce, Tomato & Cheese .................7.49 #2 CARNE ASADA BURRITO w/2 Rolled Tacos SHREDDED BEEF TACO .............................................................. 3.49 w/Guacamole & Cheese .......................................................11.99 CHIMICHANGA STYLE ... add $3.99 BURRITO BOWL .. add $2.00 NOT AVAILABLE ON SEÑOR BURRO #3 CHEESE QUESADILLA w/3 Rolled Tacos SHRIMP Simmered in Pico, Rice & Secret Baja Sauce ..................9.99 SOFT TACOS w/Guacamole & Cheese........................................................9.49 Big Size Flour or Corn Tortilla DIABLO SHRIMP Simmered in Diablo Spicy Sauce, #4 2 HARD SHELL BEEF TACOS w/Rice & Beans .......................9.49 Rice & Secret Baja Sauce ................................................................9.99 BAJA FISH ........................ 4.79 CARNITAS ....................... 4.79 SHRIMP CHIPOTLE Simmered in Chipotle Sauce, BAJA SHRIMP .................. 4.99 GRILLED CHICKEN .......... 4.79 Mushrooms, Rice & Cheese ...........................................................9.99 CARNE ASADA ............... 4.99 PICK ANY TWO SOFT FISH Baja Style w/Cabbage, Pico & Secret Baja Sauce .................9.49