Computer Oral History Collection, 1969-1973, 1977

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Creativity – Success – Obscurity

Author Gerry Pickering CREATIVITY – SUCCESS – OBSCURITY UNIVAC, WHAT HAPPENED? A fellow retiree posed the question of what happened. How did the company that invented the computer snatch defeat from the jaws of victory? The question piqued my interest, thus I tried to draw on my 32 years of experiences in the company and the myriad of information available on the Internet to answer the question for myself and hopefully others that may still be interested 60+ years after the invention and delivery of the first computers. Computers plural, as there were more than one computer and more than one organization from which UNIVAC descended. J. Presper Eckert and John Mauchly, located in Philadelphia PA are credited with inventing the first general purpose computer under a contract with the U.S. Army. But our heritage also traces back to a second group of people in St. Paul MN who developed several computers about the same time under contract with the U.S. Navy. This is the story of how these two companies started separately, merged to become one company, how that merged company named UNIVAC (Universal Automatic Computers) grew to become a main rival of IBM (International Business Machines), then how UNIVAC was swallowed by another company to end up in near obscurity compared to IBM and a changing industry. Admittedly it is a biased story, as I observed the industry from my perspective as an employee of UNIVAC. It is also biased in that I personally observed only a fraction of the events as they unfolded within UNIVAC. This story concludes with a detailed account of my work assignments within UNIVAC. -

A History of Silicon Valley the Greatest Creation of Wealth in History (An Immoral Tale) Being a Presentation by Piero Scaruffi

A History of Silicon Valley The Greatest Creation of Wealth in History (An immoral tale) being a presentation by piero scaruffi www.scaruffi.com adapted from the book “A History of Silicon Valley” Piero Scaruffi • Cultural Historian • Cognitive Scientist • Blogger • Poet • www.scaruffi.com www.scaruffi.com 2 This is Part 2 • See http://www.scaruffi.com/svhistory for the index of this Powerpoint presentation and links to the other parts – 1900-1960 – The 1960s – The 1970s – The 1980s – The 1990s – The 2000s www.scaruffi.com 3 What the book is about… • The book is a history of the high-tech industry in the San Francisco Bay Area (of which Silicon Valley is currently the most famous component) www.scaruffi.com 4 Semiconductors – Fairchild Semiconductors’ planar integrated circuit (1961) – Fairchild Semiconductors employees: Don Farina, Don Valentine, Charles Sporck, Jerry Sanders, Jack Gifford, Mike Markkula – Signetics (1961), first Fairchild spinoff – Main customers of integrated circuits: the Air Force and NASA www.scaruffi.com 5 Life Sciences • Stanford hires Carl Djerassi (1959), inventor of the birth-control pill • Alejandro Zaffaroni’s Syntex relocates to the Stanford Industrial Park (1963) www.scaruffi.com 6 Meanwhile elsewhere… • New York – IBM 7000 transistorized series (1960) – IBM’s SABRE (1960), the first online transaction processing, an adaptation of SAGE to automating American Airlines' reservation system – GE’s IDS (1961), the first database management system • Boston (MIT) – CTSS (1961), the first time-sharing system – "Spacewar" (1962), the first computer game – Ivan Sutherland’s "Sketchpad“ (1963), the first computer program with a GUI www.scaruffi.com 7 Meanwhile elsewhere… • US Government – Paul Baran (Rand Corp): a distributed network of computers can survive a nuclear strike (1962) – Ted Nelson (Harvard Univ): hypertext (1965) – Joseph Licklider (DARPA’s IPTO) funds Project MAC for A.I. -

Oral History Interview with Control Data Corporation Engineers (1975)

Reminiscences of computer architecture and computer design at Control Data Corporation CBI OH 321 Interviewee: Toth, Dolan Interviewee: Steiner, Kent Interviewee: Specker, Wayne Interviewee: Rowan, Tom Interviewee: Resnick, Dave Interviewee: Pavlov, Mike Interviewee: Pagelkopf, Don Interviewee: Moe, Robert Interviewee: Lincoln, Neil R. Interviewee: Krueger, Larry Interviewee: Krohn, Howard Interviewee: Kort, Raymon Interviewee: Hutson, Maurice Interviewee: Hawley, Charles L. Interviewee: Grinna, Dennis Interviewee: Control Data Corporation Interviewee: Bhend, Bill Interviewee: Bergmanis, Maris Interviewee: Alexander, Curt Interviewer: Neil R. Lincoln Repository: Charles Babbage Institute, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis Description: Transcript, 210 pp. Abstract: Organized discussion moderated by Neil R. Lincoln with eighteen Control Data Corporation (CDC) engineers on computer architecture and design at CDC. Engineers include: Robert Moe, Wayne Specker, Dennis Grinna, Tom Rowan, Maurice Hutson, Curt Alexander, Don Pagelkopf, Maris Bergmanis, Dolan Toth, Chuck Hawley, Larry Krueger, Mike Pavlov, Dave Resnick, Howard Krohn, Bill Bhend, Kent Steiner, Raymon Kort, and Lincoln. Citation: Reminiscences of computer architecture and computer design at Control Data Corporation, OH 321. Oral history interview moderated by Neil R. Lincoln, May and September 1975. Charles Babbage Institute, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis. Copyright: Copyright to this oral history is held by the Charles Babbage Institute. Distribution in any format of the -

The Computers Nobody Wanted: My Years at Xerox

Te Computers Nobody Wanted My Years with Xerox Other publications by Paul A. Strassmann: Information Payof: Te Transformation of Work in the Electronic Age – 1985 Te Business Value of Computers – 1990 Te Politics of Information Management – 1994 Irreverent Dictionary of Information Politics – 1995 Te Squandered Computer – 1997 Information Productivity – 1999 Information Productivity Indicators of U.S. Industrial Corporations – 2000 Revenues and Profts of Global Information Technology Suppliers – 2000 Governance of Information Management Principles & Concepts – 2000 Assessment of Productivity, Technology and Knowledge Capital – 2000 Te Digital Economy and Information Technology – 2001 Te Economics of Knowledge Capital: Analysis of European Firms – 2001 Defning and Measuring Information Productivity – 2004 Demographics of the U.S. Information Economy – 2004 Te Economics of Outsourcing in the Information Economy – 2004 Paul’s War: Slovakia, 1938 – 1945 Te Economics of Corporate Information Systems – 2007 Paul’s Odyssey: America, 1945 – 1985 Te Computers Nobody Wanted My Years with Xerox Paul A. Strassmann Te Information Econonomics Press new canaan, connecticut 2008 Copyright © 2008 by Paul A. Strassmann All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the Pub- lisher. Tis publication has been authored to provide personal recollections and opinions with regard to the subject matter covered. Published by the Information Economics Press P.O.Box 264 New Canaan, Connecticut 06840-0264 Fax: 203-966-5506 E-mail: [email protected] Design and composition: David G. Shaw, Belm Design Produced in the United States of America Strassmann, Paul A. -

IBM, Lockheed and Dassault Systemes

Chapter 13 IBM, Lockheed and Dassault Systèmes Introduction This is probably the most complicated chapter in this book in that it involves a number of different companies involved in an overlapping manner over several decades with multiple different products. It does not follow a strictly chronological format very well. Therefore, I have chosen to cover some of the following subjects over longer timeframes rather the chop them up into time-dependent chunks. Also, this is really the story of CADAM and CATIA and not of IBM per se. As a consequence, I have kept the discussion of IBM to the minimum required to put what occurred with these software products into context. Finally, although Dassault Systèmes acquired SolidWorks in 1997, that company and its products are discussed separately in Chapter 18. Lockheed’s early development of CADAM CADAM (Computer-graphics Augmented Design and Manufacturing) began as an internal mainframe application referred to as “Project Design” within Lockheed’s Burbank, California operation in 1965. It was initially implemented on IBM 360 computers using IBM’s 2250 graphics display terminals. From the start, a primary objective was to minimize response time. Working with IBM, the two companies determined that optimum productivity would be achieved if the response time for individual operations could be kept under 0.5 seconds. This was typically accomplished with CADAM although some critics claim that it was done by implementing commands that individually did less than what other systems accomplished with each command. According to these critics, the result was that it took more steps to accomplish a given set of tasks with CADAM than with competitive systems. -

Grace Hopper and Univac

TUTORIAL GRACE HOPPER AND UNIVAC GRACE HOPPER AND UNIVAC: TUTORIAL BEFORE THERE WAS COBOL In the days before cheap silicon chips, valves ruled the roost – and JULIET KEMP it took a special kind of brain to handle these magnificent beasts. fter Babbage and the (never actually built) UNIVAC was programmable. The first customers Analytical Engine in the 19th century, included the US Census Bureau and the US Air Force Acomputer development languished for a (who had the first on-site installation, in 1952). In while. During the first half of the 20th century, various 1952, as a promotional stunt, they worked with CBS to analog computers were developed, but these solved have UNIVAC predict the result of the 1952 US specific problems rather than being programmable. In presidential election. It correctly (and quickly!) 1936, Alan Turing developed the idea of the ‘Universal predicted an Eisenhower win, beating out the pollsters Machine’, and the outbreak of World War II shortly who had gone for Stevenson. So let’s take a look at afterwards was a driver for work on developing these what it was and what it was doing. machines, including UNIVAC, famously worked on by Grace Hopper. UNIVAC: mercury and diodes Grace Hopper, born in New York in 1906, was an UNIVAC weighed about 13 tons, and needed a whole associate professor of mathematics at Vassar when garage-sized room to itself, with a complicated water WWII broke out. Volunteering for the US Navy Reserve, cooling system and fans. It had 10 UNISERVO tape she was assigned to the Bureau of Ships Computation drives for input and output, 5,200 electron (vacuum) Project, where she worked on the Harvard Mark I tubes, 18,000 diodes, and a 1,000 word memory project (a calculating machine used in the war effort), (more on that in a moment); it required about 125kW from 1944–9, co-authoring several papers. -

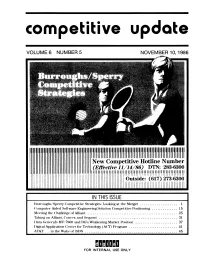

Competitive Update

competitive update VOLUME 6 NUMBER 5 NOVEMBER 10, 1986 !!!!!!!!!!I!!I!!!!!!II!I!IIII!II!!!!!!!!!!I!!!I!!I!!!!!I!!I New Competitive Hotline Number 11/14/86) DTN: 283-6300 , , H" " , f f , , , , , , , H~ II ~ rr r r , r rr rr rr , r Outside: (617) 273-6300 IN THIS ISSUE Burroughs/Sperry Comlwtitiv(' Strategies: Looking at the Merger .................... 1 COlnpllt('r-Aided Softwar'(' Engineering Solution Competitive Positioning .............. 15 Mp('t ing t.he Challenge of Alliant .................................................. 25 Taking on Alliant, CorlvPx and S('quent ........................................... 31 Data (,('neral's MV/l7HOO and UG's Weakening Market Position ....................... 37 ()i~ital Applkation Center f()J' Technology (At:'!') Progralll .......................... 41 A'I'&'r ... in tht· Wak(' of ISI)N ................................................... 45 ~D~DDmD FOR INTERNAL USE ONLY comp-etitive up-date Published monthly, Competitive Update is the official Corporate publication to communicate information regarding major competitors' products and related Digital products. distribution The readership of Competitive Update comprises PACjMSCC members, Sales, Software, Field Service, Headquarters, Order Administration, Literature Contacts and other exempt personnel. Em~IOyeeS must submit their request to Carolyn Smith via memo OG01-1jU06), VAXMAIL (SALES::SMITH), or DECMAIL (COMP _UPDA ), stating name, badge number, job code, job title, cost center and location. change of address Notification of address changes should be directed to the employee's Personnel Representative or PSA for incorporation on the individual's Employee Profile form. Processing of this information is accomplished only through the Personnel Department. administration Competitive Update is published by HEADQUARTER SALES, OG01-1jU06, STOW, and is printed and distributed by Digital's Publishing and Circulation Services in Northboro. -

OLD COMPUTERS (C) 2014 by Jeff Drobman === 1930-1944 - Largest Calculator

OLD COMPUTERS (c) 2014 by Jeff Drobman === 1930-1944 - largest calculator On August 7, 1944, IBM dedicated the Automatic Sequence Controlled Calculator (ASCC), better known as the Harvard Mark I, to Harvard University. Mark I was the largest electromechanical calculator ever built and the first automatic digital calculator in the United States at the time. As with many moments in tech history, the dedication was shadowed by disagreement. As the story goes, the machine was born out an idea for a large-scale digital calculator conceived by Howard H Aiken, a graduate student in theoretical physics at Harvard University, in 1930. IBM liked the idea and set its engineers to work with Aiken during World War II on the device. By the time of dedication, IBM had spent approximately $200,000 on the project and donated an additional $100,000 to Harvard to cover the ASCC's operating expenses. It is said that prior to dedication Aiken published a press release announcing the Mark I and listing himself as the sole inventor, only noting IBM’s James W Bryce in the release, despite IBM putting several other engineers, some of which were among IBM’s top talent at the time, on the project. Reports state that IBM CEO Thomas J Watson was enraged and only reluctantly attended the dedication ceremony and for a short time. The First "Computer" WWII was the driving force for building "automatic calculators" or "computers" for ballistics computation. The US claims the first computer was built and deployed in 1944 as "ENIAC" -- Electronic Numerical Integrator And Calculator". -

Oral History Interview with Isaac L. Auerbach

An Interview with ISAAC L. AUERBACH OH 241 Conducted by Bruce H. Bruemmer on 2-3 October 1992 Narberth, PA Charles Babbage Institute Center for the History of Information Processing University of Minnesota, Minneapolis Copyright, Charles Babbage Institute 1 Isaac L. Auerbach Interview 2-3 October 1992 Abstract Auerbach begins by discussing friction between himself and J. Presper Eckert and his reasons for leaving Eckert- Mauchly Computer Corporation. He recounts the circumstances leading to his employment from 1949-1957 with the Burroughs Corporation, his relations with Irven Travis, who headed the computer department at Burroughs, and the formation of the Burroughs Research Laboratory. He describes a number of projects he managed at Burroughs, including computer equipment for the SAGE project, BEAM I computer, the Intercontinental Ballistic Missile System, a magnetic core encryption communications system, and a missile guidance computer used for the Atlas missile. Auerbach comments on his management of the Defense, Space and Special Products Division, the general management of Burroughs, and his decision to leave the company. Auerbach outline the establishment of Auerbach Electronics (later Auerbach Associates), one of the first computer consulting firms, and describes his initial contacts with RCA (for the BMEWS system), Honeywell, Leeds and Northrup, and Hot Shoppes (Marriott). He describes the growth of the company and other ventures such as Standard Computer Corporation (computer leasing), International Systems (data processing system for parimutuel betting developed with George Skakel of Great Lakes Carbon Corporation), and Auerbach Publishers, a successful venture that became known for its computer product reviews. He describes his concern with military and government contracts, the sale of Auerbach Associates in 1976 to the Calculon Corporation, and his subsequent consulting activity. -

History of Computing at Cornell - Mike Newman

History of Computing at Cornell - Mike Newman SEARCH: Computing History Cornell Oral and Personal Histories of Computing at Cornell Introduction Timelines Stories Pictures & Poems Mike Newman Recollections, 1961 - 1999 I came to Cornell in 1960 and was in the Class of 1964, Engineering Physics. I was in Grad School for a while, working in the Cornell Center for Radiophysics and Space Research with Tom Gold among others. I was working on pulsar theory and then I got distracted flying airplanes until 1977 when I came back to Cornell as an employee. The first computer dedicated to monitoring building systems was installed in 1974 or 1975, somewhere in there, and so this was a couple of years after that. The original machine was an IBM System/7, which was diskless. The initial program loading function was done by paper tape. Whenever anybody had a change they wanted to make to the database the IBM system engineer had to go up to Syracuse and punch a new paper tape and bring it down. Somewhere about 1977, I had just started, IBM came around and said they had an upgraded System/7 that featured not only disk, but had fixed and removable platters which each held 10 Megabytes, and which had an interface which allowed you to connect serial devices like modems, for the first time. There was a company in Texas called Fischbach and Moore, F & M Systems, which had developed a multiplexer interface, a device that could communicate over a serial link at 1200 baud. This device allowed us to talk to remote multiplexers which could connect to sensors and actuators and read digitized temperatures and pressures or flows depending on the sensors. -

Mini and Micro Industries Computer 8410 Bw C.Pdf

ith today's multitiered, over- substituted for that of traditional W lapping set of programmable minicomputers, these suppliers find computer classes, where and how themselves in a situation similar to computing can be done and how BUNCH'S dilemma. For example, much it will cost can vary con- SEL and Prime, minicomputer siderably. Computing costs can be manufacturers, have marketing/ anywhere from $100 to $10 million distribution agreements with Con- (Figure 1). In addition, computing vergent Technology, but mini com- devices can include electronic panies must compete with systems typewriters with built-in communica- built from high-performance, tion capability, further increasing the commodity-oriented, 32-bit MOS- choices to be made and the complex- based microprocessors-processors ity of the information processing that provide the same performance market. as the traditional TTL-based pro- What is happening to mini and cessors at a small fraction of the cost. Market pressures have mainframe companies as the micro In short, the forecast could be forced marginal continues to pervade the industry? gloomy for mini companies. Just as One thing is that several traditional the mainframe companies were un- computer firms out of mainframe suppliers, Burroughs, able to respond to the mini, the mini business. Looking to Univac, NCR, CDC, and Honeywell companies will have difficulty mov- compatibles, wary (or BUNCH, for brevity's sake), are ing to meet the micro challenge customers are helping experiencing a declining market create de facto share as mainframe customers select standards. IBM-compatible hardware as a stan- Table 1. Minicomputer technology cir- dard and turn to other forms of com- ca 1970. -

System Development Corporation ;

MIT LIBRARIES DUPL Basement 3 TOaO DD7EflflEM 1 J*h«&,;^^ ""-x I'^'S^-B'^H omm >!fe5>i HD28 . M?t:M*'-i>£',;^ .M414 n WORKING PAPER ALFRED P. SLOAN SCHOOL OF MANAGEMENT System Development Corporation ; Defining The Factory Challenge 1 by Michael Cusumano WP 1887-87 Revised Dec, 1988 MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY 50 MEMORIAL DRIVE . CAMBRIDGE, MASSACHUSETTS 02139 OB 0^ itO CASE 1 SYSTEM DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION: DEFINING THE FACTORY CHALLENGE'' Contents Introduction Origins of SDC and the "Software Factory" Factory Components: Methodology, Organization, Tools Factory Performance: Initial Problems Revisited New Problems the Factory Created Managers' Assessments and the Japanese Challenge Conclusions INTRODUCTION System Development Corporation (SDC), established in 1956 as a subsidiary of the Rand Corporation, became part of Burroughs in 1981 and then in 1986 became a division of the Unisys Corporation after the 1986 merger of Burroughs and Sperry. In 1987, Unisys/Sperry's SDC operations, primarily in defense systems, had approximately $2.5 billion in revenues and 6,000 employees in facilities across the U.S. The company, since its inception, has specialized in large-scale, real-time applications systems, which often take years to develop and run into hundreds of thousands and often millions of lines of code. The management control problems involved in such projects persuaded SDC management in the mid-1970s to launch the first attempt in the U.S. to create a factory-type organization for software production. SDC's Software Factory was part of the larger movement among software researchers and developers during the early 1970s to reflect on various programming experiences and identify useful support tools, design and programming methods, and management procedures.