Univac Conference

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Intel Technology Journal

Intel® Technology Journal | Volume 14, Issue 1, 2010 Intel Technology Journal Publisher Managing Editor Content Architect Richard Bowles Andrew Binstock Herman D’Hooge Esther Baldwin Program Manager Technical Editor Technical Illustrators Stuart Douglas Marian Lacey InfoPros Technical and Strategic Reviewers Maria Bezaitis Ashley McCorkle Xing Su John Gustafson Milan Milenkovic Rahul Sukthankar Horst Haussecker David O‘Hallaron Allison Woodruff Badarinah Kommandur Trevor Pering Jianping Zhou Anthony LaMarca Matthai Philipose Scott Mainwaring Uttam Sengupta Intel® Technology Journal | 1 Intel® Technology Journal | Volume 14, Issue 1, 2010 Intel Technology Journal Copyright © 2010 Intel Corporation. All rights reserved. ISBN 978-1-934053-28-7, ISSN 1535-864X Intel Technology Journal Volume 14, Issue 1 No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning or otherwise, except as permitted under Sections 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750-8400, fax (978) 750-4744. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Publisher, Intel Press, Intel Corporation, 2111 NE 25th Avenue, JF3-330, Hillsboro, OR 97124-5961. E mail: [email protected]. This publication is designed to provide accurate and authoritative information in regard to the subject matter covered. It is sold with the understanding that the publisher is not engaged in professional services. If professional advice or other expert assistance is required, the services of a competent professional person should be sought. -

"Computers" Abacus—The First Calculator

Component 4: Introduction to Information and Computer Science Unit 1: Basic Computing Concepts, Including History Lecture 4 BMI540/640 Week 1 This material was developed by Oregon Health & Science University, funded by the Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology under Award Number IU24OC000015. The First "Computers" • The word "computer" was first recorded in 1613 • Referred to a person who performed calculations • Evidence of counting is traced to at least 35,000 BC Ishango Bone Tally Stick: Science Museum of Brussels Component 4/Unit 1-4 Health IT Workforce Curriculum 2 Version 2.0/Spring 2011 Abacus—The First Calculator • Invented by Babylonians in 2400 BC — many subsequent versions • Used for counting before there were written numbers • Still used today The Chinese Lee Abacus http://www.ee.ryerson.ca/~elf/abacus/ Component 4/Unit 1-4 Health IT Workforce Curriculum 3 Version 2.0/Spring 2011 1 Slide Rules John Napier William Oughtred • By the Middle Ages, number systems were developed • John Napier discovered/developed logarithms at the turn of the 17 th century • William Oughtred used logarithms to invent the slide rude in 1621 in England • Used for multiplication, division, logarithms, roots, trigonometric functions • Used until early 70s when electronic calculators became available Component 4/Unit 1-4 Health IT Workforce Curriculum 4 Version 2.0/Spring 2011 Mechanical Computers • Use mechanical parts to automate calculations • Limited operations • First one was the ancient Antikythera computer from 150 BC Used gears to calculate position of sun and moon Fragment of Antikythera mechanism Component 4/Unit 1-4 Health IT Workforce Curriculum 5 Version 2.0/Spring 2011 Leonardo da Vinci 1452-1519, Italy Leonardo da Vinci • Two notebooks discovered in 1967 showed drawings for a mechanical calculator • A replica was built soon after Leonardo da Vinci's notes and the replica The Controversial Replica of Leonardo da Vinci's Adding Machine . -

UNIVAC I Computer System

Saved from the Internet on 3/9/2010 Created by Allan Reiter UNIVAC I Computer System After you look at this yellow page go to the blue page to find out how UNIVAC I really worked. My name is Allan Reiter and in 1954 began my career with a company in St Paul, Minnesota called Engineering Research Associates (ERA) that was part of the Remington Rand Corporation. I was hired with 3 friends, Paul S. Lawson, Vernon Sandoz, and Robert Kress. We were buddies who met in the USAF where we were trained and worked on airborne radar on B-50 airplanes. In a way this was the start of our computer career because the radar was controlled by an analog computer known as the Q- 24. After discharge from the USAF Paul from Indiana and Vernon from Texas drove up to Minnesota to visit me. They said they were looking for jobs. We picked up a newspaper and noticed an ad that sounded interesting and decided to check it out. The ad said they wanted people with military experience in electronics. All three of us were hired at 1902 West Minnehaha in St. Paul. We then looked up Robert Kress (from Iowa) and he was hired a few days later. The four of us then left for Philadelphia with three cars and one wife. Robert took his wife Brenda along. This was where the UNIVAC I was being built. Parts of the production facilities were on an upper floor of a Pep Boys building. Another building on Allegheny Avenue had a hydraulic elevator operated with water pressure. -

Computer History – the Pitfalls of Past Futures

Research Collection Working Paper Computer history – The pitfalls of past futures Author(s): Gugerli, David; Zetti, Daniela Publication Date: 2019 Permanent Link: https://doi.org/10.3929/ethz-b-000385896 Rights / License: In Copyright - Non-Commercial Use Permitted This page was generated automatically upon download from the ETH Zurich Research Collection. For more information please consult the Terms of use. ETH Library TECHNIKGESCHICHTE DAVID GUGERLI DANIELA ZETTI COMPUTER HISTORY – THE PITFALLS OF PAST FUTURES PREPRINTS ZUR KULTURGESCHICHTE DER TECHNIK // 2019 #33 WWW.TG.ETHZ.CH © BEI DEN AUTOREN Gugerli, Zetti/Computer History Preprints zur Kulturgeschichte der Technik #33 Abstract The historicization of the computer in the second half of the 20th century can be understood as the effect of the inevitable changes in both its technological and narrative development. What interests us is how past futures and therefore history were stabilized. The development, operation, and implementation of machines and programs gave rise to a historicity of the field of computing. Whenever actors have been grouped into communities – for example, into industrial and academic developer communities – new orderings have been constructed historically. Such orderings depend on the ability to refer to archival and published documents and to develop new narratives based on them. Professional historians are particularly at home in these waters – and nevertheless can disappear into the whirlpool of digital prehistory. Toward the end of the 1980s, the first critical review of the literature on the history of computers thus offered several programmatic suggestions. It is one of the peculiar coincidences of history that the future should rear its head again just when the history of computers was flourishing as a result of massive methodological and conceptual input. -

Early Stored Program Computers

Stored Program Computers Thomas J. Bergin Computing History Museum American University 7/9/2012 1 Early Thoughts about Stored Programming • January 1944 Moore School team thinks of better ways to do things; leverages delay line memories from War research • September 1944 John von Neumann visits project – Goldstine’s meeting at Aberdeen Train Station • October 1944 Army extends the ENIAC contract research on EDVAC stored-program concept • Spring 1945 ENIAC working well • June 1945 First Draft of a Report on the EDVAC 7/9/2012 2 First Draft Report (June 1945) • John von Neumann prepares (?) a report on the EDVAC which identifies how the machine could be programmed (unfinished very rough draft) – academic: publish for the good of science – engineers: patents, patents, patents • von Neumann never repudiates the myth that he wrote it; most members of the ENIAC team contribute ideas; Goldstine note about “bashing” summer7/9/2012 letters together 3 • 1.0 Definitions – The considerations which follow deal with the structure of a very high speed automatic digital computing system, and in particular with its logical control…. – The instructions which govern this operation must be given to the device in absolutely exhaustive detail. They include all numerical information which is required to solve the problem…. – Once these instructions are given to the device, it must be be able to carry them out completely and without any need for further intelligent human intervention…. • 2.0 Main Subdivision of the System – First: since the device is a computor, it will have to perform the elementary operations of arithmetics…. – Second: the logical control of the device is the proper sequencing of its operations (by…a control organ. -

Technical Details of the Elliott 152 and 153

Appendix 1 Technical Details of the Elliott 152 and 153 Introduction The Elliott 152 computer was part of the Admiralty’s MRS5 (medium range system 5) naval gunnery project, described in Chap. 2. The Elliott 153 computer, also known as the D/F (direction-finding) computer, was built for GCHQ and the Admiralty as described in Chap. 3. The information in this appendix is intended to supplement the overall descriptions of the machines as given in Chaps. 2 and 3. A1.1 The Elliott 152 Work on the MRS5 contract at Borehamwood began in October 1946 and was essen- tially finished in 1950. Novel target-tracking radar was at the heart of the project, the radar being synchronized to the computer’s clock. In his enthusiasm for perfecting the radar technology, John Coales seems to have spent little time on what we would now call an overall systems design. When Harry Carpenter joined the staff of the Computing Division at Borehamwood on 1 January 1949, he recalls that nobody had yet defined the way in which the control program, running on the 152 computer, would interface with guns and radar. Furthermore, nobody yet appeared to be working on the computational algorithms necessary for three-dimensional trajectory predic- tion. As for the guns that the MRS5 system was intended to control, not even the basic ballistics parameters seemed to be known with any accuracy at Borehamwood [1, 2]. A1.1.1 Communication and Data-Rate The physical separation, between radar in the Borehamwood car park and digital computer in the laboratory, necessitated an interconnecting cable of about 150 m in length. -

Turing's Influence on Programming — Book Extract from “The Dawn of Software Engineering: from Turing to Dijkstra”

Turing's Influence on Programming | Book extract from \The Dawn of Software Engineering: from Turing to Dijkstra" Edgar G. Daylight∗ Eindhoven University of Technology, The Netherlands [email protected] Abstract Turing's involvement with computer building was popularized in the 1970s and later. Most notable are the books by Brian Randell (1973), Andrew Hodges (1983), and Martin Davis (2000). A central question is whether John von Neumann was influenced by Turing's 1936 paper when he helped build the EDVAC machine, even though he never cited Turing's work. This question remains unsettled up till this day. As remarked by Charles Petzold, one standard history barely mentions Turing, while the other, written by a logician, makes Turing a key player. Contrast these observations then with the fact that Turing's 1936 paper was cited and heavily discussed in 1959 among computer programmers. In 1966, the first Turing award was given to a programmer, not a computer builder, as were several subsequent Turing awards. An historical investigation of Turing's influence on computing, presented here, shows that Turing's 1936 notion of universality became increasingly relevant among programmers during the 1950s. The central thesis of this paper states that Turing's in- fluence was felt more in programming after his death than in computer building during the 1940s. 1 Introduction Many people today are led to believe that Turing is the father of the computer, the father of our digital society, as also the following praise for Martin Davis's bestseller The Universal Computer: The Road from Leibniz to Turing1 suggests: At last, a book about the origin of the computer that goes to the heart of the story: the human struggle for logic and truth. -

Law and Military Operations in Kosovo: 1999-2001, Lessons Learned For

LAW AND MILITARY OPERATIONS IN KOSOVO: 1999-2001 LESSONS LEARNED FOR JUDGE ADVOCATES Center for Law and Military Operations (CLAMO) The Judge Advocate General’s School United States Army Charlottesville, Virginia CENTER FOR LAW AND MILITARY OPERATIONS (CLAMO) Director COL David E. Graham Deputy Director LTC Stuart W. Risch Director, Domestic Operational Law (vacant) Director, Training & Support CPT Alton L. (Larry) Gwaltney, III Marine Representative Maj Cody M. Weston, USMC Advanced Operational Law Studies Fellows MAJ Keith E. Puls MAJ Daniel G. Jordan Automation Technician Mr. Ben R. Morgan Training Centers LTC Richard M. Whitaker Battle Command Training Program LTC James W. Herring Battle Command Training Program MAJ Phillip W. Jussell Battle Command Training Program CPT Michael L. Roberts Combat Maneuver Training Center MAJ Michael P. Ryan Joint Readiness Training Center CPT Peter R. Hayden Joint Readiness Training Center CPT Mark D. Matthews Joint Readiness Training Center SFC Michael A. Pascua Joint Readiness Training Center CPT Jonathan Howard National Training Center CPT Charles J. Kovats National Training Center Contact the Center The Center’s mission is to examine legal issues that arise during all phases of military operations and to devise training and resource strategies for addressing those issues. It seeks to fulfill this mission in five ways. First, it is the central repository within The Judge Advocate General's Corps for all-source data, information, memoranda, after-action materials and lessons learned pertaining to legal support to operations, foreign and domestic. Second, it supports judge advocates by analyzing all data and information, developing lessons learned across all military legal disciplines, and by disseminating these lessons learned and other operational information to the Army, Marine Corps, and Joint communities through publications, instruction, training, and databases accessible to operational forces, world-wide. -

Trends in Electrical Efficiency in Computer Performance

ASSESSING TRENDS IN THE ELECTRICAL EFFICIENCY OF COMPUTATION OVER TIME Jonathan G. Koomey*, Stephen Berard†, Marla Sanchez††, Henry Wong** * Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and Stanford University †Microsoft Corporation ††Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory **Intel Corporation Contact: [email protected], http://www.koomey.com Final report to Microsoft Corporation and Intel Corporation Submitted to IEEE Annals of the History of Computing: August 5, 2009 Released on the web: August 17, 2009 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Information technology (IT) has captured the popular imagination, in part because of the tangible benefits IT brings, but also because the underlying technological trends proceed at easily measurable, remarkably predictable, and unusually rapid rates. The number of transistors on a chip has doubled more or less every two years for decades, a trend that is popularly (but often imprecisely) encapsulated as “Moore’s law”. This article explores the relationship between the performance of computers and the electricity needed to deliver that performance. As shown in Figure ES-1, computations per kWh grew about as fast as performance for desktop computers starting in 1981, doubling every 1.5 years, a pace of change in computational efficiency comparable to that from 1946 to the present. Computations per kWh grew even more rapidly during the vacuum tube computing era and during the transition from tubes to transistors but more slowly during the era of discrete transistors. As expected, the transition from tubes to transistors shows a large jump in computations per kWh. In 1985, the physicist Richard Feynman identified a factor of one hundred billion (1011) possible theoretical improvement in the electricity used per computation. -

A Bibliography of Publications By, and About, Charles Babbage

A Bibliography of Publications by, and about, Charles Babbage Nelson H. F. Beebe University of Utah Department of Mathematics, 110 LCB 155 S 1400 E RM 233 Salt Lake City, UT 84112-0090 USA Tel: +1 801 581 5254 FAX: +1 801 581 4148 E-mail: [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] (Internet) WWW URL: http://www.math.utah.edu/~beebe/ 08 March 2021 Version 1.24 Abstract -analogs [And99b, And99a]. This bibliography records publications of 0 [Bar96, CK01b]. 0-201-50814-1 [Ano91c]. Charles Babbage. 0-262-01121-2 [Ano91c]. 0-262-12146-8 [Ano91c, Twe91]. 0-262-13278-8 [Twe93]. 0-262-14046-2 [Twe92]. 0-262-16123-0 [Ano91c]. 0-316-64847-7 [Cro04b, CK01b]. Title word cross-reference 0-571-17242-3 [Bar96]. 1 [Bab97, BRG+87, Mar25, Mar86, Rob87a, #3 [Her99]. Rob87b, Tur91]. 1-85196-005-8 [Twe89b]. 100th [Sen71]. 108-bit [Bar00]. 1784 0 [Tee94]. 1 [Bab27d, Bab31c, Bab15]. [MB89]. 1792/1871 [Ynt77]. 17th [Hun96]. 108 000 [Bab31c, Bab15]. 108000 [Bab27d]. 1800s [Mar08]. 1800s-Style [Mar08]. 1828 1791 + 200 = 1991 [Sti91]. $19.95 [Dis91]. [Bab29a]. 1835 [Van83]. 1851 $ $ $21.50 [Mad86]. 25 [O’H82]. 26.50 [Bab51a, CK89d, CK89i, She54, She60]. $ [Enr80a, Enr80b]. $27.95 [L.90]. 28 1852 [Bab69]. 1853 [She54, She60]. 1871 $ [Hun96]. $35.00 [Ano91c]. 37.50 [Ano91c]. [Ano71b, Ano91a]. 1873 [Dod00]. 18th $45.00 [Ano91c]. q [And99a, And99b]. 1 2 [Bab29a]. 1947 [Ano48]. 1961 Adam [O’B93]. Added [Bab16b, Byr38]. [Pan63, Wil64]. 1990 [CW91]. 1991 Addison [Ano91c]. Addison-Wesley [Ano90, GG92a]. 19th [Ano91c]. Addition [Bab43a]. Additions [Gre06, Gre01, GST01]. -

Women in Computing

History of Computing CSE P590A (UW) PP190/290-3 (UCB) CSE 290 291 (D00) Women in Computing Katherine Deibel University of Washington [email protected] 1 An Amazing Photo Philadelphia Inquirer, "Your Neighbors" article, 8/13/1957 2 Diversity Crisis in Computer Science Percentage of CS/IS Bachelor Degrees Awarded to Women National Center for Education Statistics, 2001 3 Goals of this talk ! Highlight the many accomplishments made by women in the computing field ! Learn their stories, both good and bad 4 Augusta Ada King, Countess of Lovelace ! Translated and extended Menabrea’s article on Babbage’s Analytical Engine ! Predicted computers could be used for music and graphics ! Wrote the first algorithm— how to compute Bernoulli numbers ! Developed notions of looping and subroutines 5 Garbage In, Garbage Out The Analytical Engine has no pretensions whatever to originate anything. It can do whatever we know how to order it to perform. It can follow analysis; but it has no power of anticipating any analytical relations or truths. — Ada Lovelace, Note G 6 On her genius and insight If you are as fastidious about the acts of your friendship as you are about those of your pen, I much fear I shall equally lose your friendship and your Notes. I am very reluctant to return your admirable & philosophic 'Note A.' Pray do not alter it… All this was impossible for you to know by intuition and the more I read your notes the more surprised I am at them and regret not having earlier explored so rich a vein of the noblest metal. -

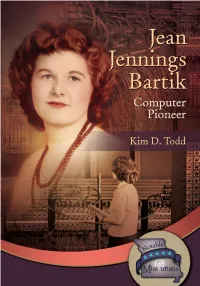

Computer Pioneer / Kim Todd

Copyright © 2015 Truman State University Press, Kirksville, Missouri, 63501 All rights reserved tsup.truman.edu Cover art: Betty Jean Jennings, ca. 1941; detail of ENIAC, 1946. Cover design: Teresa Wheeler Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Todd, Kim D., author. Jean Jennings Bartik : computer pioneer / Kim Todd. pages cm—(Notable Missourians) Summary: “As a young girl in the 1930s, Jean Bartik dreamed of adventures in the world beyond her family’s farm in northwestern Missouri. After college, she had her chance when she was hired by the U.S. Army to work on a secret project. At a time when many people thought women could not work in technical fields like science and mathematics, Jean became one of the world’s first computer programmers. She helped program the ENIAC, the first successful stored-program computer, and had a long career in the field of computer science. Thanks to computer pioneers like Jean, today we have computers that can do almost anything.”—Provided by publisher. Audience: Ages 10-12. Audience: Grades 4 to 6. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-61248-145-6 (library binding : alk. paper)—ISBN 978-1-61248-146-3 (e-book) 1. Bartik, Jean--Juvenile literature. 2. Women computer scientists—United States—Biography—Juvenile literature. 3. Computer scientists— United States—Biography—Juvenile literature. 4. Women computer programmers— United States—Biography—Juvenile literature. 5. Computer programmers—United States—Biography—Juvenile literature. 6. ENIAC (Computer)—History—Juvenile literature. 7. Computer industry—United States—History—Juvenile literature. I. Title. QA76.2.B27T63 2015 004.092--dc23 2015011360 No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any format by any means without written permission from the publisher.