Macaca Radiata) in Goa, India

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

3 Additions of Butterflies.Pmd

JoTT NOTE 1(5): 298-299 Three additions to the known butterfly 2. White-banded Awl (Hasora taminatus (Lepidoptera: Rhopalocera and Grypocera) (Hübner)) (Image 2) Family: Hesperiidae fauna of Goa, India Sub-family: Coeliadinae On 28 December 2008 one individual Parag Rangnekar 1 & Omkar Dharwadkar 2 of this species was observed mud-puddling around 1130hr along with Common Pierrot (Castalius rosimon Fabricius), Dark 1 Bldg 4, S-3, Technopark, Chogm Road, Alto-Porvorim, Goa Grass Blue (Zizeeria karsandra Moore), Common Emigrants 403001, India (Catopsilia pomona Fabricius) and Large Oakblue (Arhopala 2 Flat No. F-2, First Floor, Kurtarkar Commercial Arcade, Kaziwada, Ponda, Goa 403401, India amantes Hewitson) in the premises of “Aaranyak”, the tented Email: 1 [email protected] accommodation facility of the Department of Forest, Govt. of Goa, in the Mollem National Park. Attempts to photograph the butterfly were in vain as it flew from one spot to another Studies on the fauna of Goa are few. Compared to other and finally vertically into the canopy. Further visits to the fauna the butterflies of the State are fairly well documented. location did not result in sighting of the White-banded Awl, The most dependable study on the butterflies of the Western although the other butterflies mentioned above were present Ghats has been by Gaonkar (1996) which documents 330 at the site. The species was later photographed while mud- species of which 251 species have been reported from Goa. In puddling along the riverside at Netravali on 25 January 2009 recent works, 97 species have been documented from the Bondla by both the authors. -

The Tradition of Serpent Worship in Goa: a Critical Study Sandip A

THE TRADITION OF SERPENT WORSHIP IN GOA: A CRITICAL STUDY SANDIP A. MAJIK Research Student, Department of History, Goa University, Goa 403206 E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT: As in many other States of India, the State of Goa has a strong tradition of serpent cult from the ancient period. Influence of Naga people brought rich tradition of serpent worship in Goa. In the course of time, there was gradual change in iconography of serpent deities and pattern of their worship. There exist a few writings on serpent worship in Goa. However there is much scope to research further using recent evidences and field work. This is an attempt to analyse the tradition of serpent worship from a historical and analytical perspective. Keywords: Nagas, Tradition, Sculpture, Inscription The Ancient World The Sanskrit word naga is actually derived from the word naga, meaning mountain. Since all the Animal worship is very common in the religious history Dravidian tribes trace their origin from mountains, it of the ancient world. One of the earliest stages of the may probably be presumed that those who lived in such growth of religious ideas and cult was when human places came to be called Nagas.6 The worship of serpent beings conceived of the animal world as superior to deities in India appears to have come from the Austric them. This was due to obvious deficiency of human world.7 beings in the earliest stages of civilisation. Man not equipped with scientific knowledge was weaker than the During the historical migration of the forebears of animal world and attributed the spirit of the divine to it, the modern Dravidians to India, the separation of the giving rise to various forms of animal worship. -

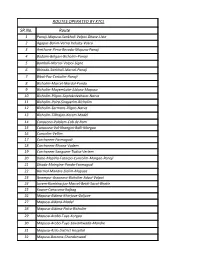

SR.No. Route ROUTES OPERATED by KTCL

ROUTES OPERATED BY KTCL SR.No. Route 1 Panaji-Mapusa-Sankhali-Valpoi-Dhave-Uste 2 Agapur-Borim-Verna Industy-Vasco 3 Amthane-Pirna-Revoda-Mapusa-Panaji 4 Badami-Belgavi-Bicholim-Panaji 5 Bamboli-Marcel-Valpoi-Signe 6 Bhiroda-Sankhali-Marcel-Panaji 7 Bibal-Paz-Cortalim-Panaji 8 Bicholim-Marcel-Mardol-Ponda 9 Bicholim-MayemLake-Aldona-Mapusa 10 Bicholim-Pilgao-Saptakoteshwar-Narva 11 Bicholim-Poira-Sinquerim-Bicholim 12 Bicholim-Sarmans-Pilgao-Narva 13 Bicholim-Tikhajan-Kerem-Madel 14 Canacona-Palolem-Cab de Ram 15 Canacona-Val-Khangini-Balli-Margao 16 Cuncolim-Vellim 17 Curchorem-Farmagudi 18 Curchorem-Rivona-Vadem 19 Curchorem-Sanguem-Tudva-Verlem 20 Dabe-Mopirla-Fatorpa-Cuncolim-Margao-Panaji 21 Dhada-Maingine-Ponda-Farmagudi 22 Harmal-Mandre-Siolim-Mapusa 23 Ibrampur-Assonora-Bicholim-Advoi-Valpoi 24 Juvem-Kumbharjua-Marcel-Betki-Savoi-Bhatle 25 Kawar-Canacona-Rajbag 26 Mapusa-Aldona-Khorjuve-Goljuve 27 Mapusa-Aldona-Madel 28 Mapusa-Aldona-Poira-Bicholim 29 Mapusa-Arabo-Tuye-Korgao 30 Mapusa-Arabo-Tuye-Sawantwada-Mandre 31 Mapusa-Azilo District Hospital 32 Mapusa-Bastora-Chandanwadi 33 Mapusa-Bicholim-Poira 34 Mapusa-Bicholim-Sankhali-Valpoi-Hivre 35 Mapusa-Calvi-Madel 36 Mapusa-Carona-Amadi 37 Mapusa-Colvale-Dadachiwadi-Madkai 38 Mapusa-Duler-Camurli 39 Mapusa-Karurli-Aldona-Pomburpa-Panaji 40 Mapusa-Khorjuve-Bicholim-Varpal 41 Mapusa-Marna-Siolim 42 Mapusa-Nachnola-Carona-Calvi 43 Mapusa-Palye-Succuro-Bitona-Panaji 44 Mapusa-Panaji-Fatorpha(Sunday) 45 Mapusa-Pedne-Pednekarwada-Mopa 46 Mapusa-Saligao-Calangute-Pilerne-Panaji 47 Mapusa-Siolim -

Goa. 403511 Phone Nos. 0832-2407189, 2407187, 2407580 Fax No

Government of Goa Department of Environment Opp. Saligao Seminary, Saligao, Bardez – Goa. 403511 Phone nos. 0832-2407189, 2407187, 2407580 Fax no. 0832-2407176 e-mail: [email protected] No: 118-10-2015/STE-DIR/61 Date: 17/04/2015 OTIFICATIO WHEREAS, the Ministry of Environment, Forests and Climate Change, Government of India vide following notifications has notified an area around the boundaries of the Wildlife Sanctuaries / National Park / Bird Sanctuary in the State of Goa, as the Eco-sensitive Zone:- 1. S.O. 221(E) dated 23/1/2015 declaring an area with an extent of one kilometre of land or the water body, whichever is near to the Bhagwan Mahaveer Wildlife Sanctuary and National Park in the State of Goa, as the Eco-sensitive Zone. 2. S.O. 615 (E) dated 25/1/2015 declaring an area with an extent of one kilometre of land or the water body, whichever is near to the Bondla Wildlife Sanctuary in the State of Goa, as the Eco-sensitive Zone. 3. S.O. 555 (E) dated 17/2/2015 declaring an area with an extent of one kilometre of land or the water body, whichever is near to the Netravali Wildlife Sanctuary in the State of Goa, as the Eco-sensitive Zone. 4. S.O. 607 (E) dated 24/2/2015 declaring an area up to the river bank abutting the Dr. Salim Ali Bird Sanctuary on the three sides of the said Sanctuary and to the extent of 100 mtrs on the eastern side towards Chorao village from the Sanctuary in the State of Goa as the Eco-sensitive Zone. -

Official Gazette Government of Go~ Daman and Did '

.L'.. r,', Panaji, 25th April, 1974 (Vaisakha 5, 18961 SERIES III No.4 OFFICIAL GAZETTE GOVERNMENT OF GO~ DAMAN AND DID ',. " , Shri D. T. -A. Nunes, is therefore, dismissed from service .GOVERNMENT OF GOA, DAMAN with effect from the date of issue of this order under rule AND DiU 19{ti) of the Central Civil .geI'VIices (ClassificatIon, COntrQl and Appeal) Ruiles, 1965. Home Department nran sport and Accommodation) M. H. SarMs~i, DIrector of Education. Panaji,/11th April, 1974. Office of the District Magistrate of Goa, • Not,fication Publ;c Works Deportment No. JUD/MV/74/245 Works Division VIII (BldgsJ - Fatorda.Margdo (Goa) Under Section 75 .'Of the Motor Vehicles Act, i939 the fo1- ilowting 'l'laces are hereby notified for fixation of signboards .~ Tender notice no. WrDVJ'hl/A'DM.6/E-!l2/74-7S as -jndicalted against their names:- The Executive Engineer, Works Divisi:on vm, P. W. D;; Name of place Type of signboard" Fatorda-Margao, inVites on behalf of the President of India, sealed tenders upto 4.00 p. m. of 29th instant for i-: 'On>pariaji-ponda road (Kin new brench 1. No entry. washing of :linen etc. of the Rest House at Mcntel Margao of -road) opposite ithe slaughter house. -Goa; -for a period of one year. ,Tenders wHl be opened on the ~~ On Pam.aji-Ponda road 'oppOsite Baiin- 1. No entry. same day at 4.30 p. m. guinim Devasthan on the old road. Earnest"inoney of Rs. 25/- should be deposited in -the State Pan'aji, 6th April, 1974,.-The District Magiistrate, S. -

North Goa District Factbook |

Goa District Factbook™ North Goa District (Key Socio-economic Data of North Goa District, Goa) January, 2018 Editor & Director Dr. R.K. Thukral Research Editor Dr. Shafeeq Rahman Compiled, Researched and Published by Datanet India Pvt. Ltd. D-100, 1st Floor, Okhla Industrial Area, Phase-I, New Delhi-110020. Ph.: 91-11-43580781, 26810964-65-66 Email : [email protected] Website : www.districtsofindia.com Online Book Store : www.datanetindia-ebooks.com Also available at : Report No.: DFB/GA-585-0118 ISBN : 978-93-86683-80-9 First Edition : January, 2017 Second Edition : January, 2018 Price : Rs. 7500/- US$ 200 © 2018 Datanet India Pvt. Ltd. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, mechanical photocopying, photographing, scanning, recording or otherwise without the prior written permission of the publisher. Please refer to Disclaimer & Terms of Use at page no. 208 for the use of this publication. Printed in India North Goa District at a Glance District came into Existence 30th May, 1987 District Headquarter Panaji Distance from State Capital NA Geographical Area (In Square km.) 1,736 (Ranks 1st in State and 522nd in India) Wastelands Area (In Square km.) 266 (2008-2009) Total Number of Households 1,79,085 Population 8,18,008 (Persons), 4,16,677 (Males), 4,01,331 (Females) (Ranks 1st in State and 480th in India) Population Growth Rate (2001- 7.84 (Persons), 7.25 (Males), 8.45 (Females) 2011) Number of Sub Sub-districts (06), Towns (47) and Villages (194) Districts/Towns/Villages Forest Cover (2015) 53.23% of Total Geographical Area Percentage of Urban/Rural 60.28 (Urban), 39.72 (Rural) Population Administrative Language Konkani Principal Languages (2001) Konkani (50.94%), Marathi (31.93%), Hindi (4.57%), Kannada (4.37%), Urdu (3.44%), Malayalam (1.00%) and Others (0.17%) Population Density 471 (Persons per Sq. -

Official Gazette

panalf.10th' February,'lm (Magha 21, 1893) SERIES III No. 46 OFFICIAL GAZETTE • GOVERNMENT' OF GOA, DAMAN AND DIU GOVERNMENT OF GOA, DAMAN from 1st April, 1972, wJrt:h right only _for !the usufruct of the e~ist!ing trees on startli1ng bId of -Rs. '555/~ under the general conditions of lease available in the office of the AND DIU Mamlatdar for consultation of the interested parties. General Administration Department , It 'is hereby made knoWiIl to aU 'concerm~d ttha.t on ~19th • February, '1972, at 10,30 a. m., publ'ic auction will be held Mamlatdar's Office of Goa Taluka' i'1 the office of the Marulatd-ar of T.iswadi 'Ta:luka, Panaj! under the Goa, Daman and Diu Lamd Revenue (Dtsposal of Government trees, Pr:oduce of trees, Gr32Jing and other Natu Notices .r~ products) Rules, 1969, for the lease of Governmentt plot .. iSItuated -near the Hospttal of Ribandar, bounded on the north -It· 'is; hereby made knoW\l1 ito all concerned that on '19th by the property ·-belonging to the _Comunidade of .Chimbel, February. '1972, at 10,30 a. m., publ'ic auction :WiH be held o:n the south by 'the propeIlty :of Mr. Vaz, on the west by. in the offf.ce 'of the Mamlatdar of Tiswad-i Taluka, Banaji the propert.y belonging to Ribandar HospItal a,.nd. on the under the Goa, Daman and Diu ·Land Revenue (Dispooal of east by Ithe property of Mr. Tarkar, for a period 'Of five Government trees, Produce of trees, Gra2iing and other Natu years ·commencing from 1st APflill, :1972, Wlilth lIight only ra}. -

Defining Goan Identity

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University History Theses Department of History 1-12-2006 Defining Goan Identity Donna J. Young Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/history_theses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Young, Donna J., "Defining Goan Identity." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2006. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/history_theses/6 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of History at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DEFINING GOAN IDENTITY: A LITERARY APPROACH by DONNA J. YOUNG Under the Direction of David McCreery ABSTRACT This is an analysis of Goan identity issues in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries using unconventional sources such as novels, short stories, plays, pamphlets, periodical articles, and internet newspapers. The importance of using literature in this analysis is to present how Goans perceive themselves rather than how the government, the tourist industry, or tourists perceive them. Also included is a discussion of post-colonial issues and how they define Goan identity. Chapters include “Goan Identity: A Concept in Transition,” “Goan Identity: Defined by Language,” and “Goan Identity: The Ancestral Home and Expatriates.” The conclusion is that by making Konkani the official state language, Goans have developed a dual Goan/Indian identity. In addition, as the Goan Diaspora becomes more widespread, Goans continue to define themselves with the concept of building or returning to the ancestral home. INDEX WORDS: Goa, India, Goan identity, Goan Literature, Post-colonialism, Identity issues, Goa History, Portuguese Asia, Official languages, Konkani, Diaspora, The ancestral home, Expatriates DEFINING GOAN IDENTITY: A LITERARY APPROACH by DONNA J. -

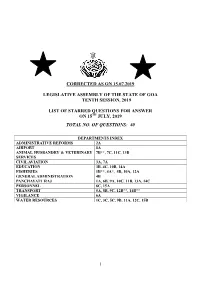

Corrected As on 15.07.2019 Legislative Assembly of The

CORRECTED AS ON 15.07.2019 LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY OF THE STATE OF GOA TENTH SESSION, 2019 LIST OF STARRED QUESTIONS FOR ANSWER ON 15TH JULY, 2019 TOTAL NO. OF QUESTIONS: 40 DEPARTMENTS INDEX ADMINISTRATIVE REFORMS 2A AIRPORT 8A ANIMAL HUSBANDRY & VETERINARY 7B**, 7C, 11C, 13B SERVICES CIVIL AVIATION 3A, 7A EDUCATION 3B, 4C, 10B, 14A FISHERIES 1B**, 4A*, 5B, 10A, 12A GENERAL ADMINISTRATION 4B PANCHAYATI RAJ 1A, 6B, 9A, 10C, 11B, 13A, 14C PERSONNEL 6C, 15A TRANSPORT 5A, 8B, 9C, 12B**, 14B** VIGILANCE 6A WATER RESOURCES 1C, 3C, 5C, 9B, 11A, 12C, 15B 1 SL. MEMBER QUESTION DEPARTMENT NO. NOS 001A PANCHAYATI RAJ 1. SHRI ISIDORE FERNANDES 001B** TRANSFERRED 00IC WATER RESOURCES 2. GLENN SOUZA TICLO 002A ADMINISTRATIVE REFORMS 003A CIVIL AVIATION 3. SHRI RAMKRISHNA 003B EDUCATION DHAVALIKAR 003C WATER RESOURCES 004A* FISHERIES 4. SHRI ALEIXO R. LOURENCO 004B GENERAL ADMINISTRATION 004C EDUCATION 005A TRANSPORT 5. SHRI JOSE LUIS CARLOS 005B FISHERIES ALMEIDA 005C WATER RESOURCES 006A VIGILANCE 6. SMT. ALINA SANDANHA 006B PANCHAYATI RAJ 006C PERSONNEL 007A CIVIL AVIATION SHRI PRATAPSINGH RANE 007B** TRANSFERRED 7. 007C ANIMAL HUSBANDRY & VETERINARY SERVICES SHRI CHANDRAKANT 008A AIRPORT 8. KAVALEKAR 008B TRANSPORT 009A PANCHAYATI RAJ 9. SHRI FRANCISCO SILVEIRA 009B WATER RESOURCES 009C TRANSPORT 010A FISHERIES 10. SHRI NILKANTH 010B EDUCATION HALARNKAR 010C PANCHAYATI RAJ 2 011A WATER RESOURCES 011B PANCHAYATI RAJ 11. SHRI RAVI NAIK 011C ANIMAL HUSBANDRY & VETERINARY SERVICES 012A FISHERIES 12. SHRI WILFRED D’SA 012B** TRANSFERRED 012C WATER RESOURCES 013A PANCHAYATI RAJ 13. SHRI PRASAD GAONKAR 013B ANIMAL HUSBANDRY & VETERINARY SERVICES 014A EDUCATION 14. SHRI FILIPE N. RODRIGUES 014B** TRANSFERRED 014C PANCHAYATI RAJ 015A PERSONNEL 15. -

Goa at a Glance - 2017 (Part A) Sl

Goa At A Glance - 2017 (Part A) Sl. NORTH GOA SOUTH GOA Total For No. ITEM Reference Tiswadi Bardez Pernem Bicholim Sattari Ponda North Goa Sanguem Dharban- Canacona Quepem Salcete Mormugao South Goa Goa Sl. Period (4 to 9) dora (11 to 16) State No. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 I POPULATION AND LITERACY I 1 Total population 2011 1,77,219 2,37,440 75,747 97,955 63,817 1,65,830 8,18,008 65,147 NAS 45,172 81,193 2,94,464 1,54,561 6,40,537 14,58,545 1 2 Density per Sq.Km. 2011 830 899 301 410 129 566 466 75 NAS 128 255 1005 1406 329 394 2 3 Total No. of household 2011 42,241 57,147 17,248 22,414 14,367 38,349 1,91,766 15,068 NAS 10,239 19,119 71,717 35,702 1,51,845 3,43,611 3 4 Male population 2011 90,136 1,19,892 38,652 49,931 32,574 85,492 4,16,677 32,623 NAS 22,532 40,722 1,45,448 81,138 3,22,463 7,39,140 4 5 Female population 2011 87,083 1,17,548 37,095 48,024 31,243 80,338 4,01,331 32,524 NAS 22,640 40,471 1,49,016 73,423 3,18,074 7,19,405 5 6 Rural population 2011 37,549 74,321 45,681 55,775 49,422 62,179 3,24,927 53,600 NAS 32,738 36,234 82,000 22,232 2,26,804 5,51,731 6 7 Urban population 2011 1,39,670 1,63,119 30,066 42,180 14,395 1,03,651 4,93,081 11,547 NAS 12,434 44,959 2,12,464 1,32,329 4,13,733 9,06,814 7 8 No. -

An Updated Checklist of Lichens from Goa with New Records from Cotigao Wildlife Sanctuary Pallavi Randive1, Sanjeeva Nayaka2 and M.K

Cryptogam Biodiversity and Assessment Randive et al. Vol 2, No. 1 (2017), e-ISSN :2456-0251, 26-36 An updated checklist of lichens from Goa with new records from Cotigao Wildlife Sanctuary Pallavi Randive1, Sanjeeva Nayaka2 and M.K. Janarthanam3* 1&3Department of Botany, Goa University, Taleigao Plateau, Goa-403206 2Lichenology Laboratory, CSIR-National Botanical Research Institute, Rana Pratap Marg, Lucknow-226001 Publication Info ABSTRACT Article history: A checklist of 118 lichens species is prepared by compiling the published literature, unreported Received : 00.00.00 species from herbarium LWG and fresh collection from Cotigao Wildlife Sanctuary. The study Accepted : 00.00.00 added 47 species as new to Goa and Anisomeridium angulosum (Müll. Arg.) R.C. Harris as new DOI: https://doi.org/10.21756/ to India. The state lichen biota is dominated by crustose lichens belonging to Graphidaceous and cab.v2i01.8609 Pyrenocarpous group. Maximum number of lichens are listed from Cotigao Wildlife Sanctuary with 67 species. The study would serve as baseline information for further studies on lichen biota Key words: as well as biomonitoring in Goa. Biodiversity, Lichenized fungi, Protected Areas, Flora, Western Ghats *Corresponding author: Email: [email protected] INTRODUCTION National Botanical Research Institute, Lucknow (CSIR- Goa state covers an area of 3702 km2 of which about NBRI, acronym LWG) lichens from Goa state are being 60% is covered with forests. The forest of Goa is part of collected since year 1962. Dr. Prakash Chandra, a botanist internationally recognized biodiversity hotspot, the Western from CSIR-NBRI was the first person to collect lichens from Ghats. -

Communication Plan 2019 North Goa District.Pdf

1 DISASTER MANAGEMENT COMMUNICATION PLAN-2019 NORTH GOA DISTRICT PANAJI-GOA. CONTROL ROOM No.1077/2225383/2225083/2427690 FAX NO.2422059 2 I N D E X Sr. No. CONTENTS PAGE NO. 1. STATE LEVEL OFFICER 2. DISTRICT LEVEL OFFICER 3. DEPUTY COLLECTOR & SDO 4. MAMLATDARS 5. POLICE DEPARTMENT 6. FIRE & EMERGENCY DEPARTMENT 7. MUNICIPAL ADMINISTRATION 8. DIRECTORATE OF PANCHAYATS 9. DIRECTORATE OF HEALTH SERVICES 10. PUBLIC WORKS DEPARTMENT 11. INDIA METEOROLOGICAL DEPARTMENT 12. DEPARTMENT OF INFORMATION AND PUBLICITY 13. CAPTAIN OF PORTS 14. DIRECTORATE OF FISHERIES 15. DIRECTORATE OF TRANSPORT 16. DIRECTORATE OF ANIMAL HUSBANDRY & VETERINARY SERVICES 17. INSPECTORATE OF FACTORIES AND BOILERS 18. DIRECTORATE OF MINES & GEOLOGY 19. WATER RESOURCES DEPARTMENT 20. FOREST DEPARTMENT 21. ELECTRICITY DEPARTMENT 22. DIRECTORATE OF CIVIL SUPPLIES & CONSUMER AFFAIRS 23. DIRECTORATE OF EDUCATION 24. DIRECTORATE OF HIGHER EDUCATION 25. BHARAT SANCHAR NIGAM LIMITED 26. LIST OF CONTRACTORS TALUKA WISE 27. VODAFONE MOBILE SERVICES DURING DISASTERS 28. LIFE GUARD SERVICES 29. DIRECTORATE OF AGRICULTURE 30. DIRECTORATE OF TOURISM 3 STATE LEVEL OFFICERS Sr. Name & Officer’s Office Phone Residence Mobile Fax No. Designation 1. Shri Parimal Rai, IAS., 2419401/2419 2224908 9779866666 2415201 Chief Secretary 402 2. Smt. Nila Mohanan, IAS. 2419409 2221315 7447429222 2419687 Secretary (Revenue) 3. Shri Anthony D’ Souza Jt. 2419435 2453067 9850926003 2419671 Secretary (Revenue) 4. Shri Sudin Natu, 2419444 23142202 9422395833 2419670 Under Secretary (Revenue -I) 5. Shri Shankar Barkelo 2419444 22249220 9822230310 2419670 Gaonkar Under Secretary (Revenue -II) 6. State Control Room 2419550/2415 ---- ---- -- 583 7. Army Central Adjutant 2STC 2226246/47/48 ---- 8975003178 2416512 Goa 8. Captain Najmulhuda 2582866/ ---- ---- 258266 CSO Goa Naval Headquarters 2582200 Vasco Da Gama (Diving Unit) 2582202/2866 Goa Naval Headquarters 294 2582202 2582200 9.