Western Prairie Ecological Landscape

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lexicon of Pleistocene Stratigraphic Units of Wisconsin

Lexicon of Pleistocene Stratigraphic Units of Wisconsin ON ATI RM FO K CREE MILLER 0 20 40 mi Douglas Member 0 50 km Lake ? Crab Member EDITORS C O Kent M. Syverson P P Florence Member E R Lee Clayton F Wildcat A Lake ? L L Member Nashville Member John W. Attig M S r ik be a F m n O r e R e TRADE RIVER M a M A T b David M. Mickelson e I O N FM k Pokegama m a e L r Creek Mbr M n e M b f a e f lv m m i Sy e l M Prairie b C e in Farm r r sk er e o emb lv P Member M i S ill S L rr L e A M Middle F Edgar ER M Inlet HOLY HILL V F Mbr RI Member FM Bakerville MARATHON Liberty Grove M Member FM F r Member e E b m E e PIERCE N M Two Rivers Member FM Keene U re PIERCE A o nm Hersey Member W le FM G Member E Branch River Member Kinnickinnic K H HOLY HILL Member r B Chilton e FM O Kirby Lake b IG Mbr Boundaries Member m L F e L M A Y Formation T s S F r M e H d l Member H a I o V r L i c Explanation o L n M Area of sediment deposited F e m during last part of Wisconsin O b er Glaciation, between about R 35,000 and 11,000 years M A Ozaukee before present. -

Guide to the Flora of the Carolinas, Virginia, and Georgia, Working Draft of 17 March 2004 -- LILIACEAE

Guide to the Flora of the Carolinas, Virginia, and Georgia, Working Draft of 17 March 2004 -- LILIACEAE LILIACEAE de Jussieu 1789 (Lily Family) (also see AGAVACEAE, ALLIACEAE, ALSTROEMERIACEAE, AMARYLLIDACEAE, ASPARAGACEAE, COLCHICACEAE, HEMEROCALLIDACEAE, HOSTACEAE, HYACINTHACEAE, HYPOXIDACEAE, MELANTHIACEAE, NARTHECIACEAE, RUSCACEAE, SMILACACEAE, THEMIDACEAE, TOFIELDIACEAE) As here interpreted narrowly, the Liliaceae constitutes about 11 genera and 550 species, of the Northern Hemisphere. There has been much recent investigation and re-interpretation of evidence regarding the upper-level taxonomy of the Liliales, with strong suggestions that the broad Liliaceae recognized by Cronquist (1981) is artificial and polyphyletic. Cronquist (1993) himself concurs, at least to a degree: "we still await a comprehensive reorganization of the lilies into several families more comparable to other recognized families of angiosperms." Dahlgren & Clifford (1982) and Dahlgren, Clifford, & Yeo (1985) synthesized an early phase in the modern revolution of monocot taxonomy. Since then, additional research, especially molecular (Duvall et al. 1993, Chase et al. 1993, Bogler & Simpson 1995, and many others), has strongly validated the general lines (and many details) of Dahlgren's arrangement. The most recent synthesis (Kubitzki 1998a) is followed as the basis for familial and generic taxonomy of the lilies and their relatives (see summary below). References: Angiosperm Phylogeny Group (1998, 2003); Tamura in Kubitzki (1998a). Our “liliaceous” genera (members of orders placed in the Lilianae) are therefore divided as shown below, largely following Kubitzki (1998a) and some more recent molecular analyses. ALISMATALES TOFIELDIACEAE: Pleea, Tofieldia. LILIALES ALSTROEMERIACEAE: Alstroemeria COLCHICACEAE: Colchicum, Uvularia. LILIACEAE: Clintonia, Erythronium, Lilium, Medeola, Prosartes, Streptopus, Tricyrtis, Tulipa. MELANTHIACEAE: Amianthium, Anticlea, Chamaelirium, Helonias, Melanthium, Schoenocaulon, Stenanthium, Veratrum, Toxicoscordion, Trillium, Xerophyllum, Zigadenus. -

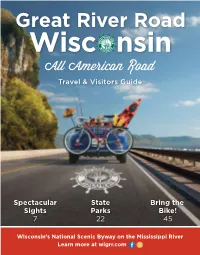

Wisconsin Great River Road, Thank You for Choosing to Visit Us and Please Return Again and Again

Great River Road Wisc nsin Travel & Visitors Guide Spectacular State Bring the Sights Parks Bike! 7 22 45 Wisconsin’s National Scenic Byway on the Mississippi River Learn more at wigrr.com THE FRESHEST. THE SQUEAKIEST. SQUEAk SQUEAk SQUEAk Come visit the Cheese Curd Capital and home to Ellsworth Premium Cheeses and the Antonella Collection. Shop over 200 kinds of Wisconsin Cheese, enjoy our premium real dairy ice cream, and our deep-fried cheese curd food trailers open Thursdays-Sundays all summer long. WOR TWO RETAIL LOCATIONS! MENOMONIE LOCATION LS TH L OPEN 7 DAYS A WEEK - 8AM - 6PM OPENING FALL 2021! E TM EST. 1910 www.EllsworthCheese.com C 232 North Wallace 1858 Highway 63 O Y O R P E Ellsworth, WI Comstock, WI E R A M AT I V E C R E Welcome to Wisconsin’s All American Great River Road! dventures are awaiting you on your 250 miles of gorgeous Avistas, beaches, forests, parks, historic sites, attractions and exciting “explores.” This Travel & Visitor Guide is your trip guide to create itineraries for the most unique, one-of-a-kind experiences you can ever imagine. What is your “bliss”? What are you searching for? Peace, adventure, food & beverage destinations, connections with nature … or are your ideas and goals to take it as it comes? This is your slice of life and where you will find more than you ever dreamed is here just waiting for you, your family, friends and pets. Make memories that you will treasure forever—right here. The Wisconsin All American Great River Road curves along the Mississippi River and bluff lands through 33 amazing, historic communities in the 8 counties of this National Scenic Byway. -

Natural Heritage Program List of Rare Plant Species of North Carolina 2012

Natural Heritage Program List of Rare Plant Species of North Carolina 2012 Edited by Laura E. Gadd, Botanist John T. Finnegan, Information Systems Manager North Carolina Natural Heritage Program Office of Conservation, Planning, and Community Affairs N.C. Department of Environment and Natural Resources 1601 MSC, Raleigh, NC 27699-1601 Natural Heritage Program List of Rare Plant Species of North Carolina 2012 Edited by Laura E. Gadd, Botanist John T. Finnegan, Information Systems Manager North Carolina Natural Heritage Program Office of Conservation, Planning, and Community Affairs N.C. Department of Environment and Natural Resources 1601 MSC, Raleigh, NC 27699-1601 www.ncnhp.org NATURAL HERITAGE PROGRAM LIST OF THE RARE PLANTS OF NORTH CAROLINA 2012 Edition Edited by Laura E. Gadd, Botanist and John Finnegan, Information Systems Manager North Carolina Natural Heritage Program, Office of Conservation, Planning, and Community Affairs Department of Environment and Natural Resources, 1601 MSC, Raleigh, NC 27699-1601 www.ncnhp.org Table of Contents LIST FORMAT ......................................................................................................................................................................... 3 NORTH CAROLINA RARE PLANT LIST ......................................................................................................................... 10 NORTH CAROLINA PLANT WATCH LIST ..................................................................................................................... 71 Watch Category -

An Annotated Checklist of the Vascular Plant Flora of Guthrie County, Iowa

Journal of the Iowa Academy of Science: JIAS Volume 98 Number Article 4 1991 An Annotated Checklist of the Vascular Plant Flora of Guthrie County, Iowa Dean M. Roosa Department of Natural Resources Lawrence J. Eilers University of Northern Iowa Scott Zager University of Northern Iowa Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy Copyright © Copyright 1991 by the Iowa Academy of Science, Inc. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uni.edu/jias Part of the Anthropology Commons, Life Sciences Commons, Physical Sciences and Mathematics Commons, and the Science and Mathematics Education Commons Recommended Citation Roosa, Dean M.; Eilers, Lawrence J.; and Zager, Scott (1991) "An Annotated Checklist of the Vascular Plant Flora of Guthrie County, Iowa," Journal of the Iowa Academy of Science: JIAS, 98(1), 14-30. Available at: https://scholarworks.uni.edu/jias/vol98/iss1/4 This Research is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa Academy of Science at UNI ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of the Iowa Academy of Science: JIAS by an authorized editor of UNI ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Jour. Iowa Acad. Sci. 98(1): 14-30, 1991 An Annotated Checklist of the Vascular Plant Flora of Guthrie County, Iowa DEAN M. ROOSA 1, LAWRENCE J. EILERS2 and SCOTI ZAGER2 1Department of Natural Resources, Wallace State Office Building, Des Moines, Iowa 50319 2Department of Biology, University of Northern Iowa, Cedar Falls, Iowa 50604 The known vascular plant flora of Guthrie County, Iowa, based on field, herbarium, and literature studies, consists of748 taxa (species, varieties, and hybrids), 135 of which are naturalized. -

2010 Animal Species of Concern

MONTANA NATURAL HERITAGE PROGRAM Animal Species of Concern Species List Last Updated 08/05/2010 219 Species of Concern 86 Potential Species of Concern All Records (no filtering) A program of the University of Montana and Natural Resource Information Systems, Montana State Library Introduction The Montana Natural Heritage Program (MTNHP) serves as the state's information source for animals, plants, and plant communities with a focus on species and communities that are rare, threatened, and/or have declining trends and as a result are at risk or potentially at risk of extirpation in Montana. This report on Montana Animal Species of Concern is produced jointly by the Montana Natural Heritage Program (MTNHP) and Montana Department of Fish, Wildlife, and Parks (MFWP). Montana Animal Species of Concern are native Montana animals that are considered to be "at risk" due to declining population trends, threats to their habitats, and/or restricted distribution. Also included in this report are Potential Animal Species of Concern -- animals for which current, often limited, information suggests potential vulnerability or for which additional data are needed before an accurate status assessment can be made. Over the last 200 years, 5 species with historic breeding ranges in Montana have been extirpated from the state; Woodland Caribou (Rangifer tarandus), Greater Prairie-Chicken (Tympanuchus cupido), Passenger Pigeon (Ectopistes migratorius), Pilose Crayfish (Pacifastacus gambelii), and Rocky Mountain Locust (Melanoplus spretus). Designation as a Montana Animal Species of Concern or Potential Animal Species of Concern is not a statutory or regulatory classification. Instead, these designations provide a basis for resource managers and decision-makers to make proactive decisions regarding species conservation and data collection priorities in order to avoid additional extirpations. -

2017 Natural Resource Management Plan

2017 Resource and Land Management Plan Mecklenburg County Park and Recreation Division of Nature Preserves and Natural Resources Natural Resources Section 1 Table of Contents Chapter 1: Introduction I. Mission and Vision II. Management Themes Chapter 2: Resource Conditions and Goals I. Theme 1: Restore and Maintain Natural Communities Vegetation - Historical and Existing Conditions Vegetation - Goals and Desired Conditions Wildlife - Existing Conditions Wildlife - Goals and Desired Conditions II. Theme 2: Gather Information to fill Knowledge Gaps of Mecklenburg Resources Knowledge Gaps - Existing Conditions Knowledge Gaps - Goals and Desired Conditions III. Theme 3: Conserving Soil and Water Resources Soil and Water - Existing Conditions Soil and Water - Goals and Desired Conditions Chapter 3: Resource Management Objectives I. General Resource Management Approaches II. Preserve-Level Management Objectives III. Vegetation and Wildlife Objectives IV. Soil and Water Objectives V. Recreation Objectives VI. Property Management and Facility Objectives VII. Research, Demonstration, and Education Objectives VIII. Volunteer Objectives Chapter 4: Special Management Considerations I. Unique and Rare Natural Resources a. Significant Natural Communities as Designated by the NC Natural Heritage Program b. Threatened and Endangered Species II. Natural Threats and Challenges a. Invasive Species, Insects, Disease, and Potential Pests b. Climate Change and Forest Management III. Land-Use Restrictions and Allowances a. Deed Use Restrictions (Conservation Easements) b. Land Acquisition Funding Restrictions c. Leases d. Utilities and Access Easements e. Ecological Conservation Areas f. Historic and Agricultural Communities Appendix and Maps 2 Chapter 1: Introduction Since 1993, Mecklenburg County Park and Recreation (MCPR) Division of Nature Preserves and Natural Resources, Natural Resource Section (NRS) has been responsible for the conservation and management of natural communities within its parks and particularly nature preserves. -

Floristic Quality Assessment Report

FLORISTIC QUALITY ASSESSMENT IN INDIANA: THE CONCEPT, USE, AND DEVELOPMENT OF COEFFICIENTS OF CONSERVATISM Tulip poplar (Liriodendron tulipifera) the State tree of Indiana June 2004 Final Report for ARN A305-4-53 EPA Wetland Program Development Grant CD975586-01 Prepared by: Paul E. Rothrock, Ph.D. Taylor University Upland, IN 46989-1001 Introduction Since the early nineteenth century the Indiana landscape has undergone a massive transformation (Jackson 1997). In the pre-settlement period, Indiana was an almost unbroken blanket of forests, prairies, and wetlands. Much of the land was cleared, plowed, or drained for lumber, the raising of crops, and a range of urban and industrial activities. Indiana’s native biota is now restricted to relatively small and often isolated tracts across the State. This fragmentation and reduction of the State’s biological diversity has challenged Hoosiers to look carefully at how to monitor further changes within our remnant natural communities and how to effectively conserve and even restore many of these valuable places within our State. To meet this monitoring, conservation, and restoration challenge, one needs to develop a variety of appropriate analytical tools. Ideally these techniques should be simple to learn and apply, give consistent results between different observers, and be repeatable. Floristic Assessment, which includes metrics such as the Floristic Quality Index (FQI) and Mean C values, has gained wide acceptance among environmental scientists and decision-makers, land stewards, and restoration ecologists in Indiana’s neighboring states and regions: Illinois (Taft et al. 1997), Michigan (Herman et al. 1996), Missouri (Ladd 1996), and Wisconsin (Bernthal 2003) as well as northern Ohio (Andreas 1993) and southern Ontario (Oldham et al. -

Complete Iowa Plant Species List

!PLANTCO FLORISTIC QUALITY ASSESSMENT TECHNIQUE: IOWA DATABASE This list has been modified from it's origional version which can be found on the following website: http://www.public.iastate.edu/~herbarium/Cofcons.xls IA CofC SCIENTIFIC NAME COMMON NAME PHYSIOGNOMY W Wet 9 Abies balsamea Balsam fir TREE FACW * ABUTILON THEOPHRASTI Buttonweed A-FORB 4 FACU- 4 Acalypha gracilens Slender three-seeded mercury A-FORB 5 UPL 3 Acalypha ostryifolia Three-seeded mercury A-FORB 5 UPL 6 Acalypha rhomboidea Three-seeded mercury A-FORB 3 FACU 0 Acalypha virginica Three-seeded mercury A-FORB 3 FACU * ACER GINNALA Amur maple TREE 5 UPL 0 Acer negundo Box elder TREE -2 FACW- 5 Acer nigrum Black maple TREE 5 UPL * Acer rubrum Red maple TREE 0 FAC 1 Acer saccharinum Silver maple TREE -3 FACW 5 Acer saccharum Sugar maple TREE 3 FACU 10 Acer spicatum Mountain maple TREE FACU* 0 Achillea millefolium lanulosa Western yarrow P-FORB 3 FACU 10 Aconitum noveboracense Northern wild monkshood P-FORB 8 Acorus calamus Sweetflag P-FORB -5 OBL 7 Actaea pachypoda White baneberry P-FORB 5 UPL 7 Actaea rubra Red baneberry P-FORB 5 UPL 7 Adiantum pedatum Northern maidenhair fern FERN 1 FAC- * ADLUMIA FUNGOSA Allegheny vine B-FORB 5 UPL 10 Adoxa moschatellina Moschatel P-FORB 0 FAC * AEGILOPS CYLINDRICA Goat grass A-GRASS 5 UPL 4 Aesculus glabra Ohio buckeye TREE -1 FAC+ * AESCULUS HIPPOCASTANUM Horse chestnut TREE 5 UPL 10 Agalinis aspera Rough false foxglove A-FORB 5 UPL 10 Agalinis gattingeri Round-stemmed false foxglove A-FORB 5 UPL 8 Agalinis paupercula False foxglove -

Fifty Years in the Northwest: a Machine-Readable Transcription

Library of Congress Fifty years in the Northwest L34 3292 1 W. H. C. Folsom FIFTY YEARS IN THE NORTHWEST. WITH AN INTRODUCTION AND APPENDIX CONTAINING REMINISCENCES, INCIDENTS AND NOTES. BY W illiam . H enry . C arman . FOLSOM. EDITED BY E. E. EDWARDS. PUBLISHED BY PIONEER PRESS COMPANY. 1888. G.1694 F606 .F67 TO THE OLD SETTLERS OF WISCONSIN AND MINNESOTA, WHO, AS PIONEERS, AMIDST PRIVATIONS AND TOIL NOT KNOWN TO THOSE OF LATER GENERATION, LAID HERE THE FOUNDATIONS OF TWO GREAT STATES, AND HAVE LIVED TO SEE THE RESULT OF THEIR ARDUOUS LABORS IN THE TRANSFORMATION OF THE WILDERNESS—DURING FIFTY YEARS—INTO A FRUITFUL COUNTRY, IN THE BUILDING OF GREAT CITIES, IN THE ESTABLISHING OF ARTS AND MANUFACTURES, IN THE CREATION OF COMMERCE AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF AGRICULTURE, THIS WORK IS RESPECTFULLY DEDICATED BY THE AUTHOR, W. H. C. FOLSOM. PREFACE. Fifty years in the Northwest http://www.loc.gov/resource/lhbum.01070 Library of Congress At the age of nineteen years, I landed on the banks of the Upper Mississippi, pitching my tent at Prairie du Chien, then (1836) a military post known as Fort Crawford. I kept memoranda of my various changes, and many of the events transpiring. Subsequently, not, however, with any intention of publishing them in book form until 1876, when, reflecting that fifty years spent amidst the early and first white settlements, and continuing till the period of civilization and prosperity, itemized by an observer and participant in the stirring scenes and incidents depicted, might furnish material for an interesting volume, valuable to those who should come after me, I concluded to gather up the items and compile them in a convenient form. -

The Lower Rush River

THE LOWER RUSH RIVER Prepared by Carl A. Nelson October 22, 2019 The Lower Rush River: Present Health and a Call to Action Carl Nelson Carl is an engineer, landowner, and trout fisherman. From his first introduction to the Driftless Area more than 45 years ago, he has developed a deep connection to the land. He has owned and managed 200 acres of forested and agricultural land in Maiden Rock, Wisconsin since 1988. He is past chair of the Wisconsin Woodland Owners Association (WWOA) West Central Chapter, and an active member of The Prairie Enthusiasts, St. Croix Valley chapter. He holds a Ph.D. in Structural Engineering from the University of Minnesota. He was formerly vice president of ESI Engineering in Minneapolis, and currently is a registered Professional Engineer in Minnesota, Wisconsin, Iowa, and Nebraska. As stated in the title, this report is “A Call to Action,” and those wishing to join an exploratory working group are encouraged to contact Carl at [email protected]. Cover Photo: Sediment deposit during spring floods of 2019 with maple-basswood forest on slope in background. Section 16 Salem Township. Carl Nelson photo. The Lower Rush River: Present Health and a Call to Action Introduction The Rush River is a tributary of the Mississippi River lying almost entirely within Pierce County in west central Wisconsin, approximately 50 miles southeast of St. Paul, Minnesota. The river valley is a mosaic of different natural and man-made landscapes: from forested hillsides and dolomite bluffs to agricultural fields to flood plain forests and open wetlands. These landscapes include a variety of natural communities and pockets of relatively undisturbed land. -

Wisconsin's Wildlife Action Plan (2005-2015)

Wisconsin’s Wildlife Action Plan (2005-2015) IMPLEMENTATION: Priority Conservation Actions & Conservation Opportunity Areas Prepared by: Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources with Assistance from Conservation Partners, June 30th, 2008 06/19/2008 page 2 of 93 Wisconsin’s Wildlife Action Plan (2005-2015) IMPLEMENTATION: Priority Conservation Actions & Conservation Opportunity Areas Acknowledgments Wisconsin’s Wildlife Action Plan is a roadmap of conservation actions needed to ensure our wildlife and natural communities will be with us in the future. The original plan provides an immense volume of data useful to help guide conservation decisions. All of the individuals acknowledged for their work compiling the plan have a continuous appreciation from the state of Wisconsin for their commitment to SGCN. Implementing the conservation actions is a priority for the state of Wisconsin. To put forward a strategy for implementation, there was a need to develop a process for priority decision-making, narrowing the list of actions to a more manageable number, and identifying opportunity areas to best apply conservation actions. A subset of the Department’s ecologists and conservation scientists were assigned the task of developing the implementation strategy. Their dedicated commitment and tireless efforts for wildlife species and natural community conservation led this document. Principle Process Coordinators Tara Bergeson – Wildlife Action Plan Implementation Coordinator Dawn Hinebaugh – Data Coordinator Terrell Hyde – Assistant Zoologist (Prioritization