The Lower Rush River

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lexicon of Pleistocene Stratigraphic Units of Wisconsin

Lexicon of Pleistocene Stratigraphic Units of Wisconsin ON ATI RM FO K CREE MILLER 0 20 40 mi Douglas Member 0 50 km Lake ? Crab Member EDITORS C O Kent M. Syverson P P Florence Member E R Lee Clayton F Wildcat A Lake ? L L Member Nashville Member John W. Attig M S r ik be a F m n O r e R e TRADE RIVER M a M A T b David M. Mickelson e I O N FM k Pokegama m a e L r Creek Mbr M n e M b f a e f lv m m i Sy e l M Prairie b C e in Farm r r sk er e o emb lv P Member M i S ill S L rr L e A M Middle F Edgar ER M Inlet HOLY HILL V F Mbr RI Member FM Bakerville MARATHON Liberty Grove M Member FM F r Member e E b m E e PIERCE N M Two Rivers Member FM Keene U re PIERCE A o nm Hersey Member W le FM G Member E Branch River Member Kinnickinnic K H HOLY HILL Member r B Chilton e FM O Kirby Lake b IG Mbr Boundaries Member m L F e L M A Y Formation T s S F r M e H d l Member H a I o V r L i c Explanation o L n M Area of sediment deposited F e m during last part of Wisconsin O b er Glaciation, between about R 35,000 and 11,000 years M A Ozaukee before present. -

Wisconsin Great River Road, Thank You for Choosing to Visit Us and Please Return Again and Again

Great River Road Wisc nsin Travel & Visitors Guide Spectacular State Bring the Sights Parks Bike! 7 22 45 Wisconsin’s National Scenic Byway on the Mississippi River Learn more at wigrr.com THE FRESHEST. THE SQUEAKIEST. SQUEAk SQUEAk SQUEAk Come visit the Cheese Curd Capital and home to Ellsworth Premium Cheeses and the Antonella Collection. Shop over 200 kinds of Wisconsin Cheese, enjoy our premium real dairy ice cream, and our deep-fried cheese curd food trailers open Thursdays-Sundays all summer long. WOR TWO RETAIL LOCATIONS! MENOMONIE LOCATION LS TH L OPEN 7 DAYS A WEEK - 8AM - 6PM OPENING FALL 2021! E TM EST. 1910 www.EllsworthCheese.com C 232 North Wallace 1858 Highway 63 O Y O R P E Ellsworth, WI Comstock, WI E R A M AT I V E C R E Welcome to Wisconsin’s All American Great River Road! dventures are awaiting you on your 250 miles of gorgeous Avistas, beaches, forests, parks, historic sites, attractions and exciting “explores.” This Travel & Visitor Guide is your trip guide to create itineraries for the most unique, one-of-a-kind experiences you can ever imagine. What is your “bliss”? What are you searching for? Peace, adventure, food & beverage destinations, connections with nature … or are your ideas and goals to take it as it comes? This is your slice of life and where you will find more than you ever dreamed is here just waiting for you, your family, friends and pets. Make memories that you will treasure forever—right here. The Wisconsin All American Great River Road curves along the Mississippi River and bluff lands through 33 amazing, historic communities in the 8 counties of this National Scenic Byway. -

Western Prairie Ecological Landscape

Chapter 23 Western Prairie Ecological Landscape Where to Find the Publication The Ecological Landscapes of Wisconsin publication is available online, in CD format, and in limited quantities as a hard copy. Individual chapters are available for download in PDF format through the Wisconsin DNR website (http://dnr.wi.gov/, keyword “landscapes”). The introductory chapters (Part 1) and supporting materials (Part 3) should be downloaded along with individual ecological landscape chapters in Part 2 to aid in understanding and using the ecological landscape chapters. In addition to containing the full chapter of each ecological landscape, the website highlights key information such as the ecological landscape at a glance, Species of Greatest Conservation Need, natural community management opportunities, general management opportunities, and ecological landscape and Landtype Association maps (Appendix K of each ecological landscape chapter). These web pages are meant to be dynamic and were designed to work in close association with materials from the Wisconsin Wildlife Action Plan as well as with information on Wisconsin’s natural communities from the Wisconsin Natural Heritage Inventory Program. If you have a need for a CD or paper copy of this book, you may request one from Dreux Watermolen, Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, P.O. Box 7921, Madison, WI 53707. Photos (L to R): Prothonotary Warbler, photo by John and Karen Hollingsworth, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service; prairie ragwort, photo by Dick Bauer; Loggerhead Shrike, photo by Dave Menke; yellow gentian, photo by June Dobberpuhl; Blue-winged Teal, photo by Jack Bartholmai. Suggested Citation Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources. 2015. The ecological landscapes of Wisconsin: An assessment of ecological resources and a guide to planning sustainable management. -

Fifty Years in the Northwest: a Machine-Readable Transcription

Library of Congress Fifty years in the Northwest L34 3292 1 W. H. C. Folsom FIFTY YEARS IN THE NORTHWEST. WITH AN INTRODUCTION AND APPENDIX CONTAINING REMINISCENCES, INCIDENTS AND NOTES. BY W illiam . H enry . C arman . FOLSOM. EDITED BY E. E. EDWARDS. PUBLISHED BY PIONEER PRESS COMPANY. 1888. G.1694 F606 .F67 TO THE OLD SETTLERS OF WISCONSIN AND MINNESOTA, WHO, AS PIONEERS, AMIDST PRIVATIONS AND TOIL NOT KNOWN TO THOSE OF LATER GENERATION, LAID HERE THE FOUNDATIONS OF TWO GREAT STATES, AND HAVE LIVED TO SEE THE RESULT OF THEIR ARDUOUS LABORS IN THE TRANSFORMATION OF THE WILDERNESS—DURING FIFTY YEARS—INTO A FRUITFUL COUNTRY, IN THE BUILDING OF GREAT CITIES, IN THE ESTABLISHING OF ARTS AND MANUFACTURES, IN THE CREATION OF COMMERCE AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF AGRICULTURE, THIS WORK IS RESPECTFULLY DEDICATED BY THE AUTHOR, W. H. C. FOLSOM. PREFACE. Fifty years in the Northwest http://www.loc.gov/resource/lhbum.01070 Library of Congress At the age of nineteen years, I landed on the banks of the Upper Mississippi, pitching my tent at Prairie du Chien, then (1836) a military post known as Fort Crawford. I kept memoranda of my various changes, and many of the events transpiring. Subsequently, not, however, with any intention of publishing them in book form until 1876, when, reflecting that fifty years spent amidst the early and first white settlements, and continuing till the period of civilization and prosperity, itemized by an observer and participant in the stirring scenes and incidents depicted, might furnish material for an interesting volume, valuable to those who should come after me, I concluded to gather up the items and compile them in a convenient form. -

Wisconsin's Wildlife Action Plan (2005-2015)

Wisconsin’s Wildlife Action Plan (2005-2015) IMPLEMENTATION: Priority Conservation Actions & Conservation Opportunity Areas Prepared by: Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources with Assistance from Conservation Partners, June 30th, 2008 06/19/2008 page 2 of 93 Wisconsin’s Wildlife Action Plan (2005-2015) IMPLEMENTATION: Priority Conservation Actions & Conservation Opportunity Areas Acknowledgments Wisconsin’s Wildlife Action Plan is a roadmap of conservation actions needed to ensure our wildlife and natural communities will be with us in the future. The original plan provides an immense volume of data useful to help guide conservation decisions. All of the individuals acknowledged for their work compiling the plan have a continuous appreciation from the state of Wisconsin for their commitment to SGCN. Implementing the conservation actions is a priority for the state of Wisconsin. To put forward a strategy for implementation, there was a need to develop a process for priority decision-making, narrowing the list of actions to a more manageable number, and identifying opportunity areas to best apply conservation actions. A subset of the Department’s ecologists and conservation scientists were assigned the task of developing the implementation strategy. Their dedicated commitment and tireless efforts for wildlife species and natural community conservation led this document. Principle Process Coordinators Tara Bergeson – Wildlife Action Plan Implementation Coordinator Dawn Hinebaugh – Data Coordinator Terrell Hyde – Assistant Zoologist (Prioritization -

Western Coulee and Ridges Ecological Landscape

Western Coulee and Ridges ecological landscape Attributes and Characteristics Legacy Places This ecological landscape is characterized by Bad Axe River highly eroded, unglaciated topography. Steep-sided BX SW Snow Bottom- valleys are heavily forested and often managed BA Badger Army Blue River Valley for hardwood production. Agricultural activities, Ammunition Plant SP Spring Green Prairie primarily dairy and beef farming, are typically Badlands Thompson Valley confined to valley floors and ridge tops. Large, BN TV meandering rivers with broad floodplains are also BH Baraboo Hills Savanna characteristic of this landscape. They include the BO Baraboo River TR Trempealeau River Mississippi, Wisconsin, Chippewa, Black, La Crosse, Trimbelle River and Kickapoo. The floodplain forests associated with BE Black Earth Creek TB these riverine systems are among the largest in the BR Black River UD Upper Red Upper Midwest. Spring fed, coldwater streams that BU Buffalo River Cedar River support robust brown and brook trout fisheries are common throughout the area. Soils are typically silt CO Coulee Coldwater Along the Mississippi loams (loess) and sandy loams in the uplands and Riparian Resources Western Coulee & Ridges & Coulee Western alluvial or terrace deposits in the valley floors. CE Coulee Experimental Forest River corridor BT Battle Bluff Prairie FM Fort McCoy CV Cassville to GR Grant and Rattlesnake Rivers BARRON POLK Bagley Bluffs LANGLADE TAYLOR GC Greensand Cuesta UD OCONTO CY Cochrane City Bluffs EYER CHIPPEWA M ST CROIX MENOMINEE Hay -

ATTACHMENT 1 Short·Term Work Plan

ATTACHMENT 1 Short·Term Work Plan 2018 WIMRPC Work Plan Draft Revised 1/15/18 Expense Estimated Date of Program/Project Amount Lead Completion Funding Source(s) 1 Complete CMP/Strategic Action Plan Sherry Q. Mar-18 NSB Grant 2 Launch Friends of WIGRR Sherry Q. Ongoing Operating Fund 3 Visitor Guide/Marketing Plan Amy Mar-18 Visitor Guide Profits 4 Interpretative Center Updates $ - Dennis Jul-18 n/a 5 Genoa Fish Hatchery Opening $ 1,000 Dennis Spring 2018 Operating Fund 6 Education 7 Accounting (new volunteer or hire) Sherry Q. Feb 1 2018 8 Monarch Butterfly Program $ 200 Dennis Spring 2018 Operating Fund 9 WIGRR 80th Anniversary 10 Review/Revise Mission Statement $ - Sherry Q. n/a 11 Hire Executive Director Amy G & Peter F Overhead/Other Expenses Total Expenses $ 1,200 Projected Estimated Revenue Available Date of Revenue Source/Fundraising Strategy Amount Lead Revenue Total Revenue -Total Expenses Projected Annual Net ATTACHMENT 2 Survey Summary Report Summary Report: Wisconsin Great River Road National Scenic Byway Stakeholder Survey The purpose of the survey was to collect feedback from stakeholders in advance of the Wisconsin Mississippi River Parkway Commission's (WIMRPC) upcoming strategic planning retreat. Understanding the priorities of byway communities can help ensure the WIMPRC commits to projects that have widespread community support. The data also provides insight as to what stakeholders perceive as the benefits of working with the WIMPRC. A link to the online survey was distributed to approximately 350 email addresses of Wisconsin Great River Road stakeholders including elected officials, business owners, residents, and nonprofit and government agency representatives and staff. -

Legacy Places by County

Buffalo County SL Shoveler Lakes-Black Earth Trench Fond du Lac County Jefferson County Legacy Places BU Buffalo River SG Sugar River CD Campbellsport Drumlins BK Bark and Scuppernong Rivers CY Cochrane City Bluffs UL Upper Yahara River and Lakes GH Glacial Habitat Restoration Area CW Crawfish River-Waterloo Drumlins by County Lower Chippewa River and Prairies Horicon Marsh Jefferson Marsh LC Dodge County HM JM TR Trempealeau River KM Kettle Moraine State Forest KM Kettle Moraine State Forest Crawfish River-Waterloo Drumlins UM Upper Mississippi River National CW MI Milwaukee River LK Lake Koshkonong to Kettle Glacial Habitat Restoration Area Adams County Wildlife and Fish Refuge GH NE Niagara Escarpment Moraine Corridor Horicon Marsh CG Central Wisconsin Grasslands HM SY Sheboygan River Marshes UR Upper Rock River Niagara Escarpment CU Colburn-Richfield Wetlands Burnett County NE Upper Rock River MW Middle Wisconsin River CA Chase Creek UR Forest County Juneau County Clam River Chequamegon-Nicolet National Forests Badlands NN Neenah Creek CR Door County CN BN CX Crex Meadows LH Laona Hemlock Hardwoods BO Baraboo River QB Quincy Bluff and Wetlands Chambers Island DS Danbury to Sterling Corridor CI PE Peshtigo River CF Central Wisconsin Forests Colonial Waterbird Nesting Islands Ashland County NB Namekagon-Brule Barrens CS UP Upper Wolf River GC Greensand Cuesta Door Peninsula Hardwood Swamps AI Apostle Islands NR Namekagon River DP LL Lower Lemonweir River Eagle Harbor to Toft Point Corridor BD Bad River SX St. Croix River EH Grant County -

The Story of Pierce County

The Story of Pierce County From The Spring Valley (Wisconsin) Sun 1904-1906 by X.Y.Z (Allen P. Weld) Reprinted by Brookhaven Press La Crosse, Wisconsin From the Rare Book Collection of the Wisconsin Historical Society Library The Story of Wpii^^^^ BYX-Y.Z. About forty years after the landing of the Pilgrim Fathers at Pl^-j mouth Rock, some hardy French Voyageurs crossed the territory lyi^ between the Great Lakes and the Mississippi River for the purpose liii exploration and of establishing- trading* posts for trading^ with th^ Indians. Among- the names of these daring* adventurers we find that of Menard, who visited the Father of Waters in 1661; but no trace re mains of his work. Tn 1680 Father Hennepin, a French priest, came across what is now I known as the State of Wisconsin, probably by way of the Wisconsin River, and ascended to the Falls of St. Anthony, meeting- on the way another Frenchman who afterwards became famous as a border warrior and Indian trader, and who Is best known as Duluth. The latter seems to have come from the head of Lake Superior, crossing- the portage between the watershed of the lakes and that of the St. Croix river and descending* the latter to its mouth. He met Father Hennepin near the site of Prescott, and with him followed up the great river to the falls. This company seem to have given the name of the Falls of St. Anthony of Padua to the magnificent falls, and in their records of the expedition described them in g^lowing colors. -

Pierce County Hazard Mitigation Plan

Hazard Mitigation Plan Pierce County, Wisconsin Page 1 Plan Updated – August 2019 EPTEC, INC Lenora G. Borchardt 7027 Fawn Lane Sun Prairie, WI53590-9455 608-358-4267 [email protected] Page 2 Table of Contents Table of Contents ............................................................................................................ 3 Acronyms ........................................................................................................................ 7 Introduction and Background ........................................................................................ 10 Previous Planning Efforts and Legal Basis ......................................................... 11 Plan Preparation, Adoption and Maintenance .................................................... 15 Physical Characteristics of Pierce County ..................................................................... 20 General Community Introduction ........................................................................ 20 Plan Area ............................................................................................................ 20 Geology .............................................................................................................. 21 Topography ........................................................................................................ 22 Mississippi River ................................................................................................. 23 Climate .............................................................................................................. -

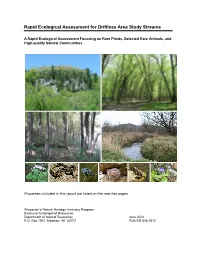

Driftless Area Streams Is Also Provided to Assist in Developing the Regional and Property Analysis That Is Part of the Master Plan

Rapid Ecological Assessment for Driftless Area Study Streams A Rapid Ecological Assessment Focusing on Rare Plants, Selected Rare Animals, and High-quality Natural Communities Properties included in this report are listed on the next two pages Wisconsin’s Natural Heritage Inventory Program Bureau of Endangered Resources Department of Natural Resources June 2012 P.O. Box 7921, Madison, WI 53707 PUB-ER-836 2012 Properties included in this report, grouped by county: Chippewa ▪ Elk Creek Fishery Area Jackson ▪ Sand Creek Fishery Area ▪ Albion Rearing Station ▪ Beaver Creek Rearing Station Crawford ▪ Buffalo River Fishery Area ▪ Gordon's Bay Landing Public Access ▪ Buffalo River Trail Prairies SNA ▪ La Crosse Area Comprehensive Fishery ▪ Half Moon Bottoms SNA Area ▪ Half Moon Lake Fishery Area/Statewide ▪ Statewide Public Access Habitat Areas ▪ Stream Bank Protection Fee Program ▪ Halls (Stockwell) Creek Fishery Area ▪ Rush Creek SNA (FM-owned parcels) ▪ North Branch Trempealeau River Fishery Area Dane ▪ REM-So Branch Trempealeau River ▪ Black Earth Creek Fishery Area ▪ REM-Washington Coulee ▪ Mount Vernon Creek Fishery Area ▪ Sand Creek Streambank Protection ▪ REM-Elvers Creek Area ▪ Stream Bank Protection Fee Program ▪ Smith Pond Fishery Area ▪ Stream Bank Protection Fee Program Dunn ▪ Tank Creek Fishery Area ▪ Bolen Creek Fishery Area ▪ Trump Coulee Rearing Station ▪ Lake Menomin Fishery Area ▪ REM-Elk Creek La Crosse ▪ REM-Gilbert Creek ▪ Statewide Habitat Areas ▪ REM-Otter Creek ▪ Coon Creek Fishery Area ▪ REM-Tainter Lake Spawning Marsh -

Prairie Du Chien, Lynxville, Ferryville, De Soto (62 Miles to Prairie Du Chien, Southern Gateway) Best Places to Fish

WISCONSIN Great River Road TRAVEL & VISITOR GUIDE Wisconsin’s National Scenic Byway on the Mississippi River | Learn more at wigrr.com ALL-NATURAL FRESH WHOLESOME DELICIOUS World Famous Wisconsin Cheese A REAL TREASURE OF THE MIDWEST! COME VISIT THE CHEESE CURD CAPITAL AND HOME TO BLASER’S PREMIUM CHEESES, THE ANTONELLA COLLECTION, ELLSWORTH VALLEY AND KAMMERUDE GOUDAS. TWO RETAIL LOCATIONS! OPEN 7 DAYS A WEEK - 9AM-6PM 232 NORTH WALLACE 1858 HIGHWAY 63 ELLSWORTH, WI COMSTOCK, WI ELLSWORTHCHEESE.COM LIKE US AT /ELLSWORTHCHEESE Welcome to the Mississippi River & Wisconsin’s Only National Scenic Byway… the Great River Road! t is my pleasure to welcome you to Wisconsin’s Great IRiver Road, voted the “Prettiest drive in America” by readers of The Huffington Post. This stunning 250- mile drive on Wisconsin State Highway 35 parallels the Mississippi River and winds through 33 delightful river towns that are just waiting to be explored. From Prescott to Potosi, the Great River Road is home to breathtaking bluff views, countless recreational activi- ties and old-fashioned hospitality that will make you feel right at home. Take your time to savor the journey with side trips that include biking, hiking, fishing and paddling. Discover historic towns dotted with boutiques, artist’s galleries and wineries, and find cozy lodging at one of the many charming bed and breakfasts. As you page through this visitor guide, you will find plenty of useful information to help you plan your trip. More resources and great travel information are also available at TravelWisconsin.com, on your desktop, tablet or mobile device.