Saint Croix NSR: Historic Resource Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lexicon of Pleistocene Stratigraphic Units of Wisconsin

Lexicon of Pleistocene Stratigraphic Units of Wisconsin ON ATI RM FO K CREE MILLER 0 20 40 mi Douglas Member 0 50 km Lake ? Crab Member EDITORS C O Kent M. Syverson P P Florence Member E R Lee Clayton F Wildcat A Lake ? L L Member Nashville Member John W. Attig M S r ik be a F m n O r e R e TRADE RIVER M a M A T b David M. Mickelson e I O N FM k Pokegama m a e L r Creek Mbr M n e M b f a e f lv m m i Sy e l M Prairie b C e in Farm r r sk er e o emb lv P Member M i S ill S L rr L e A M Middle F Edgar ER M Inlet HOLY HILL V F Mbr RI Member FM Bakerville MARATHON Liberty Grove M Member FM F r Member e E b m E e PIERCE N M Two Rivers Member FM Keene U re PIERCE A o nm Hersey Member W le FM G Member E Branch River Member Kinnickinnic K H HOLY HILL Member r B Chilton e FM O Kirby Lake b IG Mbr Boundaries Member m L F e L M A Y Formation T s S F r M e H d l Member H a I o V r L i c Explanation o L n M Area of sediment deposited F e m during last part of Wisconsin O b er Glaciation, between about R 35,000 and 11,000 years M A Ozaukee before present. -

HIGHWAY DEPARTMENT: an Inventory of Its State Park Maps

MINNESOTA HISTORICAL SOCIETY Minnesota State Archives HIGHWAY DEPARTMENT An Inventory of Its State Park Maps OVERVIEW OF THE RECORDS Agency: Minnesota. Dept. of Highways. Series Title: State park maps, Dates: 1922. Abstract: Blueprint maps showing boundaries and facilities in state parks. Quantity: 22 items in oversize folder. Location: A3/ov4 Drawer 2 SCOPE AND CONTENTS OF THE RECORDS Blueprint maps showing boundaries and facilities in various state parks, with proposed expansions of the park's land area or the addition of facilities. Most show plot plans and give elevation information. The maps were drawn by the Highway Department on orders of Governor J. A. O. Preus for use in legislative deliberations regarding park budgets, according to information printed on the maps. RELATED MATERIALS Related materials: Later state park maps, created by the state Conservation Department, are found with that department's records. INDEX TERMS This collection is indexed under the following headings in the catalog of the Minnesota Historical Society. Researchers desiring materials about related topics, persons or places should search the catalog using these headings. Topics: Mapping. Parks--Minnesota--Maps. Parks--Minnesota--Finance. Types of Documents: Hghwy005.inv HIGHWAY DEPARTMENT. State Park Maps, 1922. p. 2 Maps--Minnesota. Site plans--Minnesota. ADMINISTRATIVE INFORMATION Preferred Citation: [Indicate the cited item here]. Minnesota. Dept. of Highways. State park maps, 1922. Minnesota Historical Society. State Archives. See the Chicago Manual of Style for additional examples. Accession Information: Accession number(s): 991-52 Processing Information: PALS ID No.: 0900036077 RLIN ID No.: MNHV94-A228 ITEM LIST Note to Researchers: To request materials, please note the location and drawer number shown below. -

Dedication Saint Croix Island National Mo Ment

DEDICATION of the Establishment of SAINT CROIX ISLAND as a NATIONAL MO MENT sponsored by the United States National Park Service and the Calais Cha1nber of Commerce • June 307 1968 I --- • • • ST. CROIX ISLAND DEDICATION COM·MITIEE Frank H. Fenderson, Chairman J. Dexter Thomas Charles F. Gillis, Col. USAF, Ret. • John C. McFaul • Robert L. Treworgy Louis E. Ayoob , Richard Burgess Jay and Jane Hinson .. .. ' • • - - - - ---- - •? s.·u r JZw.· .. .-... " • ' .. PROGRAM OF TH1E DAY 1 ( 1Master of -Ceremonies, Colonel Charles F. Gillis, USAF, _Ret. ) . 1. Invocation -- - Rev. J. Andrew Arseneau, Pastor, Immacu·Iate Conception Church, Calais 2. Welcoming Remarks - Mr. Philip B. Hume, Chairman, ·Calais City Council i ' 3. Presentation of'· Colors - Sher1nan Brothers American Legion Post No. 3, Bernard Rigley, Peter Jestings, Roscoe Johnson, Gerry Ross 4. Singing of National Anthems - By audience with music by Star-Spangled. Banner Calais Memorial High School 0 Canada Band, Joseph Driscoll directing (See page 16 for verses) 5. Formal Delivery to U.S. National Park Service · of Title to Parke.,. Family Interest in Land ... Mr. Barrett Parker Acceptance by U.S. National Park Service - Mr. Lemuel A. Garrison, Regional Director, - U.S. National Park Service ... 7. .Remarks - - - Hon. Lawrence Stuart, Director of Maine State ·Park and Recreational Commission (representing Kenneth M. Curtis, Governor _of Maine) 8. RespOMe .. - Hon. Wallace E. Bird, Lieutenant- ' Govetnor o.f the Province of ·New Brunswick 9. Remarks - ---- Senator Edmund S. Muskie 10. Address - - . - ... · Dr. Ernest ·A. Connally, Chief, Office of Archeological and Historic Research, U.S. ·National Park Service 11. Cloring Remarks - Mr. Frank H. Fenderson, Chairman, Dedication of Establishment of St. -

![August 2019 SFI Review [PDF]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5856/august-2019-sfi-review-pdf-145856.webp)

August 2019 SFI Review [PDF]

Wisconsin DNR State Lands 101 South Webster Street Madison, WI 53703 SFI 2015-2019 Standards and Rules® Section 2: Forest Management Standard 2019 Surveillance Audit Printed: December 2, 2019 NSF Forestry Program Audit Report A. Certificate Holder Wisconsin DNR State Lands NSF Customer Number 1Y941 Contact Information (Name, Title, Phone & Email) Mark A. Heyde Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources Phone: (608) 220-9780 [email protected] B. Scope of Certification Forest management operations on approximately 1,543,367 acres of WI State Lands. The SFI Standard certification number is NSF-SFI-FM-1Y941. Locations Included in the Certification Categories included in the DNR Lands forest certification review include: • Northern and Southern State Forests • State Parks • State Recreation Trails • State Wildlife Areas (including leased federal lands, Meadow Valley W.A.) • State Fisheries Areas • State Natural Areas • Natural Resource Protection and Management Areas • Lower Wisconsin Riverway • State Wild Rivers • State Owned Islands • Stewardship Demonstration Forests The following DNR properties (about 37,798 acres) are excluded from the certification project: • Agricultural fields (due to potential GMO issue) • Stream Bank Protection Areas (eased lands not under DNR management) • Forest Legacy Easements (eased lands not under DNR management) • States Fish Hatcheries and Rearing Ponds (intensive non-forest use) • State Forest Nurseries (intensive non-forest use) • Nonpoint Pollution Control Easements (eased lands not under DNR management) • Poynette Game Farm and McKenzie Environmental Center (intensive non-forest use) • Boat Access Sites (intensive non-forest use) • Fire Tower Sites (intensive non-forest use) • Radio Tower Sites (intensive non-forest use) • Ranger Stations (intensive non-forest use) • Administrative Offices and Storage Buildings (intensive non-forest use) • State Park Intensively Developed Recreation Areas (intensive non-forest use) e.g. -

Table 4.1. the Political Subdivisions of the Antilles, Size of the Islands, and Representative Climatic Data

Table 4.1. The political subdivisions of the Antilles, size of the islands, and representative climatic data. sl= sea level. Compiled from various sources. Area (km2) Climatic data Site/elev. (m) MAT(oC) MAP (mm/yr) Greater Antilles (total area 207,435 km2) Cuba 110,860 Nueva Gerona 65 25.3 1793 Pinar del Rio 26 1610 Havana 26 25.1 1211 Cienguegos 32 24.6 98.3 Camajuani 110 22.8 1402 Camagữey 114 25.2 1424 Santiago de Cuba 38 26.1 1089 Hispaniola 76,480 Haiti 27,750 Bayeux 12 24.7 2075 Les Cayes 7 25.7 2042 Ganthier 76 26.2 792 Port-au-Prince 41 26.6 1313 Dominican Republic 48,730 Pico Duarte 2960 - (est. 12) 1663 Puerto Plata 13 25.5 1663 Sanchez 16 25.2 1963 Ciudad Trujillo 19 25.5 1417 Jamaica 10,991 S. Negril Point 10 25.7 1397 Kingston 8 26.1 830 Morant Point sl 26.5 1590 Hill Gardens 1640 16.7 2367 Puerto Rico 9104 Comeiro Falls 160 24.7 2011 Humacao 32 22.3 2125 Mayagữez 6 25 2054 Ponce 26 25.8 909 San Juan 32 25.6 1595 Cayman Islands 264 Lesser Antilles (total area 13,012 km 2) Antigua and Barbuda 81 Antigua and Barbada 441 Aruba 193 Barbados 440 Bridgetown sl 27 1278 Bonaire 288 British Virgin Islands 133 Curaçao 444 Dominica 790 26.1 1979 Grenada 345 24.0 4165 Guadeloupe 1702 21.3 2630 Martinique 1095 23.2 5273 Montesarrat 84 Saba 13 Saint Barthelemy 21 Saint Kitts and Nevis 306 Saint Lucia 613 Saint Marin 3453 Saint Vicent and the Grenadines 389 Sint Eustaius 21 Sint Maarten 34 Trinidad and Tobago 5131 + 300 Trinidad Port-of-Spain 28 26.6 1384 Piarco 11 26 185 Tobago Crown Point 3 26.6 1463 U.S. -

Isanti County Parks and Recreation Plan (PDF)

ISANTI COUNTY PARKS & R ECREATION PLAN ISANTI COUNTY PARKS AND RECREATION COMMISSION FINAL REPORT JANUARY, 2008 PREPARED BY THE CENTER FOR RURAL DESIGN, UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA Isanti County Parks and Recreation Plan Study Team Members/Roles: Principal Investigator: Dewey Thorbeck, Director, Center for Rural Design Center for Rural Design Team Members: Steve Roos, Senior Research Fellow Tracey Sokolski, Research Fellow Steering Committee Members: Bill Carlson, Co-Chair Joe Crocker, Co-Chair Maureen Johnson, Secretary Bonita Torpe Carol Urness George Larson George Wimmer Heidi Eaves Joan Lenzmeier Larae Klocksien Maurie Anderson Myrl Moran Steve Nelson Tom Pagel Wayne Anderson Dennis Olson Acknowledgements: This project could not have been accomplished without the cooperation and knowledge of the Isanti County Steering Committee. In addition, we owe thanks to the Isanti County Parks and Recreation Commission especially Co-Chair Bill Carlson, Co-Chair Joe Crocker and Secretary Maureen Johnson for facilitating the Committee’s work and the community workshops. January 2008 Center for Rural Design College of Design and College of Food, Agricultural and Natural Resources Sciences University of Minnesota T ABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION 1: INTRODUCTION Pg. 9 SECTION 2: RECREATIONAL OPPORTUNITIES IN ISANTI COUNTY Pg. 19 SECTION 3: GOALS AND POLICIES Pg. 85 SECTION 4: PLANNING AND ACQUISITION Pg. 97 SECTION 5: FINANCIAL SUPPORT Pg. 109 SECTION 6: BENEFITS Pg. 115 SECTION 7: NATURAL RESOURCE MANAGEMENT, Isanti County MAINTENANCE AND PROTECTION Pg. 121 APPENDICES APPENDIX A: REFERENCES & ABBREVIATIONS Pg. 125 APPENDIX B: TREND DATA Pg. 129 APPENDIX C: SYNOPSIS OF PUBLIC ENGAGEMENT Pg. 133 ADDENDUM 1: ISANTI COUNTY PARKS AND BIKE PATH MASTER PLAN Parks Plan 2008 1 INDEX O F FIGURES Figure 1. -

Minnesota Statutes 2020, Chapter 85

1 MINNESOTA STATUTES 2020 85.011 CHAPTER 85 DIVISION OF PARKS AND RECREATION STATE PARKS, RECREATION AREAS, AND WAYSIDES 85.06 SCHOOLHOUSES IN CERTAIN STATE PARKS. 85.011 CONFIRMATION OF CREATION AND 85.20 VIOLATIONS OF RULES; LITTERING; PENALTIES. ESTABLISHMENT OF STATE PARKS, STATE 85.205 RECEPTACLES FOR RECYCLING. RECREATION AREAS, AND WAYSIDES. 85.21 STATE OPERATION OF PARK, MONUMENT, 85.0115 NOTICE OF ADDITIONS AND DELETIONS. RECREATION AREA AND WAYSIDE FACILITIES; 85.012 STATE PARKS. LICENSE NOT REQUIRED. 85.013 STATE RECREATION AREAS AND WAYSIDES. 85.22 STATE PARKS WORKING CAPITAL ACCOUNT. 85.014 PRIOR LAWS NOT ALTERED; REVISOR'S DUTIES. 85.23 COOPERATIVE LEASES OF AGRICULTURAL 85.0145 ACQUIRING LAND FOR FACILITIES. LANDS. 85.0146 CUYUNA COUNTRY STATE RECREATION AREA; 85.32 STATE WATER TRAILS. CITIZENS ADVISORY COUNCIL. 85.33 ST. CROIX WILD RIVER AREA; LIMITATIONS ON STATE TRAILS POWER BOATING. 85.015 STATE TRAILS. 85.34 FORT SNELLING LEASE. 85.0155 LAKE SUPERIOR WATER TRAIL. TRAIL PASSES 85.0156 MISSISSIPPI WHITEWATER TRAIL. 85.40 DEFINITIONS. 85.016 BICYCLE TRAIL PROGRAM. 85.41 CROSS-COUNTRY-SKI PASSES. 85.017 TRAIL REGISTRY. 85.42 USER FEE; VALIDITY. 85.018 TRAIL USE; VEHICLES REGULATED, RESTRICTED. 85.43 DISPOSITION OF RECEIPTS; PURPOSE. ADMINISTRATION 85.44 CROSS-COUNTRY-SKI TRAIL GRANT-IN-AID 85.019 LOCAL RECREATION GRANTS. PROGRAM. 85.021 ACQUIRING LAND; MINNESOTA VALLEY TRAIL. 85.45 PENALTIES. 85.04 ENFORCEMENT DIVISION EMPLOYEES. 85.46 HORSE -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 110 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 110 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION Vol. 154 WASHINGTON, TUESDAY, JUNE 3, 2008 No. 90 House of Representatives The House met at 2 p.m. and was THE JOURNAL On January 5, 2007, 1 day after his called to order by the Speaker pro tem- The SPEAKER pro tempore. The 40th birthday, Rabbi Goodman became pore (Mr. JACKSON of Illinois). Chair has examined the Journal of the a United States citizen. last day’s proceedings and announces Rabbi Goodman is the co-author of f to the House his approval thereof. ‘‘Hagadah de Pesaj,’’ which is the most Pursuant to clause 1, rule I, the Jour- widely used edition of The Pesach Hagadah used in Latin America. DESIGNATION OF THE SPEAKER nal stands approved. Singled-out by international leaders PRO TEMPORE f for both his ideas and hard work, The SPEAKER pro tempore laid be- PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE Felipe became vice president of the fore the House the following commu- The SPEAKER pro tempore. Will the World Union of Jewish Students. nication from the Speaker: gentlewoman from Nevada (Ms. BERK- He is one of 12 members of The Rab- WASHINGTON, DC, LEY) come forward and lead the House binic Cabinet of The Chancellor of The June 3, 2008. in the Pledge of Allegiance. Jewish Theological Seminary and I hereby appoint the Honorable JESSE L. Ms. BERKLEY led the Pledge of Alle- serves as a member of The Joint Place- JACKSON, Jr., to act as Speaker pro tempore giance as follows: ment Commission of The Rabbinical on this day. -

Transhemispheric Exchange of Lyme Disease Spirochetes by Seabirds BJO¨ RN OLSEN,1,2 DAVID C

JOURNAL OF CLINICAL MICROBIOLOGY, Dec. 1995, p. 3270–3274 Vol. 33, No. 12 0095-1137/95/$04.0010 Copyright q 1995, American Society for Microbiology Transhemispheric Exchange of Lyme Disease Spirochetes by Seabirds BJO¨ RN OLSEN,1,2 DAVID C. DUFFY,3 THOMAS G. T. JAENSON,4 ÅSA GYLFE,1 1 1 JONAS BONNEDAHL, AND SVEN BERGSTRO¨ M * Department of Microbiology1 and Department of Infectious Diseases,2 Umeå University, S-901 87 Umeå, and Department of Zoology, Section of Entomology, and Zoological Museum, University of Uppsala, S-752 36 Uppsala,4 Sweden, and Alaska Natural Heritage Program, Environment and Natural Resources Institute, University of Alaska, Anchorage, Anchorage, Alaska 995013 Received 19 June 1995/Returned for modification 17 August 1995/Accepted 18 September 1995 Lyme disease is a zoonosis transmitted by ticks and caused by the spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato. Epidemiological and ecological investigations to date have focused on the terrestrial forms of Lyme disease. Here we show a significant role for seabirds in a global transmission cycle by demonstrating the presence of Lyme disease Borrelia spirochetes in Ixodes uriae ticks from several seabird colonies in both the Southern and Northern Hemispheres. Borrelia DNA was isolated from I. uriae ticks and from cultured spirochetes. Sequence analysis of a conserved region of the flagellin (fla) gene revealed that the DNA obtained was from B. garinii regardless of the geographical origin of the sample. Identical fla gene fragments in ticks obtained from different hemispheres indicate a transhemispheric exchange of Lyme disease spirochetes. A marine ecological niche and a marine epidemiological route for Lyme disease borreliae are proposed. -

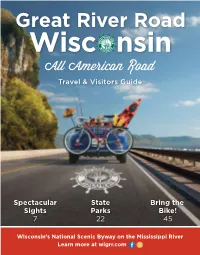

Wisconsin Great River Road, Thank You for Choosing to Visit Us and Please Return Again and Again

Great River Road Wisc nsin Travel & Visitors Guide Spectacular State Bring the Sights Parks Bike! 7 22 45 Wisconsin’s National Scenic Byway on the Mississippi River Learn more at wigrr.com THE FRESHEST. THE SQUEAKIEST. SQUEAk SQUEAk SQUEAk Come visit the Cheese Curd Capital and home to Ellsworth Premium Cheeses and the Antonella Collection. Shop over 200 kinds of Wisconsin Cheese, enjoy our premium real dairy ice cream, and our deep-fried cheese curd food trailers open Thursdays-Sundays all summer long. WOR TWO RETAIL LOCATIONS! MENOMONIE LOCATION LS TH L OPEN 7 DAYS A WEEK - 8AM - 6PM OPENING FALL 2021! E TM EST. 1910 www.EllsworthCheese.com C 232 North Wallace 1858 Highway 63 O Y O R P E Ellsworth, WI Comstock, WI E R A M AT I V E C R E Welcome to Wisconsin’s All American Great River Road! dventures are awaiting you on your 250 miles of gorgeous Avistas, beaches, forests, parks, historic sites, attractions and exciting “explores.” This Travel & Visitor Guide is your trip guide to create itineraries for the most unique, one-of-a-kind experiences you can ever imagine. What is your “bliss”? What are you searching for? Peace, adventure, food & beverage destinations, connections with nature … or are your ideas and goals to take it as it comes? This is your slice of life and where you will find more than you ever dreamed is here just waiting for you, your family, friends and pets. Make memories that you will treasure forever—right here. The Wisconsin All American Great River Road curves along the Mississippi River and bluff lands through 33 amazing, historic communities in the 8 counties of this National Scenic Byway. -

Inventory of Art in the Minnesota State Capitol March 2013

This document is made available electronically by the Minnesota Legislative Reference Library as part of an ongoing digital archiving project. http://www.leg.state.mn.us/lrl/lrl.asp Minnesota Historical Society - State Capitol Historic Site Inventory of Art in the Minnesota State Capitol March 2013 Key: Artwork on canvas affixed to a surface \ Artwork that is movable (framed or a bust) Type Installed Name Artist Completed Location Mural 1904 Contemplative Spirit of the East Cox. Kenyon 1904 East Grand Staircase Mural 1904 Winnowing Willett, Arthur (Artist) Garnsey. Elmer 1904 East Grand Staircase Mural 1904 Commerce Willett. Arthur (Artist) Garnsey. Elmer 1904 East Grand Staircase Mural 1904 Stonecutting Willett. Arthur (Artist) Garnsey. Elmer 1904 East Grand Staircase Mural 1904 Mill ing Willett. Arthur (Artist) Garnsey, Elmer 1904 East Grand Staircase Mural 1904 Mining Willett Arthur (Artist) Garnsey, Elmer 1904 East Grand Staircase Mural 1904 Navigation Willett Arthur (Artist) Garnsey. Elmer 1904 East Grand Staircase Mural 1904 Courage Willett, Arthur (Artist) Garnsey, Elmer 1904 Senate Chamber Mural 1904 Equality Willett, Arthur (Artist) Garnsey, Elmer 1904 Senate Chamber Mural 1904 Justice Willett. Arthur (Artist) Garnsey, Elmer 1904 Senate Chamber Mural 1904 Freedom Willett. Arthur (Artist) Garnsey. Elmer 1904 Senate Chamber Mural 1905 Discovers and Civilizers Led Blashfield. Edwin H. 1905 Senate Chamber, North Wall ' to the Source of the Mississippi Mural 1905 Minnesota: Granary of the World Blashfield, Edwin H. 1905 Senate Chamber, South Wall Mural 1905 The Sacred Flame Walker, Henry Oliver 1903 West Grand Staircase (Yesterday. Today and Tomorrow) Mural 1904 Horticulture Willett, Arthur (Artist) Garnsey, Elmer 1904 West Grand Staircase Mural 1904 Huntress Willett, Arthur (Artist) Garnsey, Elmer 1904 West Grand Staircase Mural 1904 Logging Willett. -

Official List of Wisconsin's State Historic Markers

Official List of Wisconsin’s State Historical Markers Last Revised June, 2019 The Wisconsin State Historical Markers program is administered by Local History-Field Services section of the Office of Programs and Outreach. If you find a marker that has been moved, is missing or damaged, contact Janet Seymour at [email protected] Please provide the title of the marker and its current location. Each listing below includes the official marker number, the marker’s official name and location, and a map index code that corresponds to Wisconsin’s Official State Highway Map. You may download or request this year’s Official State Highway Map from the Travel W isconsin website. Markers are generally listed chronologically by the date erected. The marker numbers below jump in order, since in some cases markers have been removed for a variety of reason. For instance over time the wording of some markers has become outdated, in others historic properties being described have been moved or demolished. Number Name and Location Map Index 1. Peshtigo Fire Cemetery ................................................................................................................................5-I Peshtigo Cemetery, Oconto Ave, Peshtigo, Marinette County 2. Jefferson Prairie Settlement ........................................................................................................................11-G WI-140, 4 miles south of Clinton, Rock County 5. Shake Rag.................................................................................................................................................................10-E